Previously, I wrote about TOKYO FILMeX’s online screening. This time, I’d like to talk introduce two films from the Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF), which was held around the same time as TOKYO FILMeX. These films focus on the reality of immigrants in Japan.

Two multi-language films that confront the reality of immigrants in Japan

Conversations in foreign languages at convenient stores or on the streets — this phenomenon is fast becoming the norm. According to OECD, in 2016, Japan was the fourth country with the largest migrant population. The increase in varying languages should come as no surprise. However, perhaps there are quite a few people that pay no attention to foreign languages besides English. Even if people converse with foreigners, they’re bound to stay nameless in people’s memory. Tokyo International Film Festival screened two films that shine a light on and give a voice and name to such foreigners: Along the Sea (2020) by Akio Fujimoto and Come and Go (2020) by Lim Kah Wai.

Along the Sea, directed by Akio Fujimoto

Along the Sea is a narrative film that follows three “technical intern trainees” from Vietnam named Phuong, An, and Nhu. The young women run away from their harsh workplace one night in search of a new one. When dawn breaks in snowy Aoyama, a Vietnamese broker takes them to a fishing harbor, where they work for the fishers and have a place to stay. Like before, the labor there is demanding, and they’re now illegal workers, which puts them in a perilous position. Phuong becomes ill, but the hospital refuses to take her in because her former workplace withheld her papers. With no medical attention, her health further deteriorates —

The two layers of “coldness” throughout the film are hard to ignore. The first layer is Aoyama’s bleak, cloudy scenery, and painful cold, and the second is society’s attitude towards the three women. It’s not just the Japanese residents and authorities that give them the cold shoulder, but their fellow Vietnamese people too. They mercilessly corner Phuong, An, and Nhu. Fujimoto expresses the young women’s isolation and despair through shots of Aoyama’s winter landscape and society’s cold attitude towards illegal workers. In the latter half of the film, the camera closely hovers around one woman. The long take, taken by a hand-held camera, brilliantly depicts the hopelessness she feels from being thrown into a foreign environment. It also shows the uncertainty she has about her future. Along the Sea is a minimalistic film that doesn’t have a lot of dialogue. Nonetheless, Vietnamese is used as the primary language, aside from Japanese. It wouldn’t be strange if a Vietnamese audience thought a Vietnamese director directed it.

This is Fujimoto’s second film on migrants. In response to the question, “are you going to continue filming immigrants in Japan?” he replied, “my life’s work is thinking about migrants; this comes before shooting films.” In his previous narrative film, Passage of Life (2018), he confronts the predicaments foreigners living in Japan go through, a la a Myanmarese family in Japan. In this film, the spoken language aside from Japanese is Burmese. Fujimoto’s signature style consists of a hand-held camera that follows the subjects closely and realistic dialogue from immigrants in their mother tongue. His films feel so lifelike that they come across as documentaries. They’re reminiscent of Hirokazu Koreeda’s work in some ways. Regarding how language is applied and how closely the camera follows the protagonists, Along the Sea is deeper than Passage of Life.

From the spring of 2021, Along the Sea is going to be shown in theaters nationwide. I am hopeful it’ll make its way to other countries, especially Vietnam. If the film ends up being shown in Vietnam, I would love to ask for Vietnam’s innovative director, Trần Dũng Thanh Huy’s thoughts. The director is currently filming his next film, Tick It, which is about young Vietnamese people attempting to enter the U.K. in a refrigerated container in quest of a better life. One could say this film was inspired by a case that transpired in October 2019, where 39 Vietnamese people’s bodies were found in a refrigerated container. Tick It and Along the Sea have two things in common: the theme of “coldness” and the focus on young Vietnamese people who choose to migrate. In Huy’s Ròm (2019), his impressive debut feature-length film, a young boy fights tooth and nail to survive the alleys of Ho Chi Minh. The hand-held camera shots are worth noting here. Another similarity between Fujimoto and Huy is their age. Huy was born in 1990, while Fujimoto was born in 1988. More importantly, the acting in both directors’ works are intensely realistic, and both directors try to tell the stories of society’s often-forgotten people.

Come and Go, directed by Lim Kah Wai

Lim Kah Wai’s Come and Go (2020) is set in the Umeda district of Kita, Osaka, during the springtime of 2019. This ambitious film with a big cast is roughly 158 minutes long. The unique part about Come and Go is that about half of the main characters are from other Asian countries: nine Asian countries, to be exact.

For instance, a porn addict comes to buy adult entertainment merchandise from Taiwan. Lee Kang-sheng, known for his roles in Ming-liang Tsai’s films, plays this role.

The rest is: Liên Bỉnh Phát, the actor who played the protagonist in The Tap Box (Song Lang) (2018), plays a Vietnamese “technical intern trainee” that escapes a printing factory that refuses to let him go back to his home country. Nang Tracy plays a student from Myanmar who works at the same factory and a convenience store. David Siu Chung Hang, known for his role as Ting How-hai in Hong Kong’s legendary TV series, The Greed of Man, plays a Chinese tour guide. JC Chee plays the part of a Malaysian man who comes to Japan to discuss his Halal business. Mousam Gurung, a famous singer from Nepal, plays a refugee who has an affair and works at a café in Nakazakicho. Lee Kwang-soo plays a Japanese-Korean broker who brings young Korean women to Osaka for work. Gouzi plays the role of a middle-aged Chinese tourist who visits Japan for the first time. Further, Seiji Chihara plays a police detective who’s working on a case that involves the discovery of the skeletal remains of an old woman. Makiko Watanabe acts as a Japanese language teacher who’s married to the detective and is having an affair with the Nepali refugee. Manami Usumaru plays a woman who comes to Osaka from Tokushima and gets scouted to do porn, and the person who scouts her is an Okinawan man who runs a porn production company, acted by Shogen. Orson Mochizuki plays a young part-time worker who gets involved in a dangerous job related to a gang. Jakukaju Katsura plays an elderly man who works hard at being a “middle-aged man for rent” (Ossan Rental) and lives close to where the skeleton was found. This myriad of characters goes beyond nationality and class in Kita, and some of their lives intertwine, while others don’t.

Come and Go is Kah Wai’s last film of his Osaka trilogy. His first one, The New World (2011), is set in Shinsekai, the old district around Tsutenkaku, and illustrates China-Japan relations. Kah Wai’s second film, Fly Me to Minami (2013), is set in the Minami district of Shinsaibashi and portrays a romance between Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong. From The New World to Come and Go, he starts at the very south, Shinsekai, and makes his way to the north side. Throughout his trilogy, he goes through the entertainment district, Shinsekai, and Minami in Naniwa and Shinsaibashi, and Umeda in Kita. The director listens to the foreign languages heard in convenience stores and on the streets and shows Osaka from a pan-Asian perspective. Naturally, the Osaka dialect and different Asian languages are spoken in his trilogy. In Fly Me to Minami, Japanese (Osaka dialect), Mandarin, Cantonese, and English are used. In Come and Go, per the increase of characters, the number of languages is larger too; Japanese, English, Beijing dialect, Korean, Nepali, Vietnamese, and Burmese. Kah Wai’s passion for incorporating many languages can be seen in his Balkans trilogy too, such as No Where, Now Here (2018) and Somewhen, Somewhere (showing at Cine Nouveau in Osaka from January 2nd, 2021 and at Cinema Rosa in Ikebukuro from January 23rd, 2021).

He is sure to be regarded as one of the top directors in the world, in terms of using different languages. Perhaps his home country of Malaysia influenced his multi-language films, a nation with a wide range of languages. For him, a society with multi-nationalities equates to the use of multi-languages. Originally from Myanmar, Midi Z is a director based in Taiwan. His short film, The Palace On The Sea (2014) incorporates Mandarin, Burmese, Indonesian, Thai, and Vietnamese and shows Taiwan’s diverse languages. It’s not a stretch to say that both Kah Wai and Midi Z are like-minded “cinema drifters” who carry the view of “multi-nationalities mean multi-languages.”

Both Fujimoto and Kah Wai diversify their multi-national and multi-language films by putting subtitles on foreign languages that usually get drowned out by the hustle and bustle of daily life and by giving a name and voice to foreign nationals.

Perhaps the spread of both directors’ films will help Japan come to terms with its growing migrant/immigrant population. I can’t help but pray for Along the Sea and Come and Go to show in theaters here.

Kah Wai tweeted: “I was thinking of making a spin-off, rather than a short story. The spin-off could follow each of the characters in the epilogue [of Come and Go]. For instance, the Chinese character could go to Taiwan to visit Shiokan, Mayumi could go to Malaysia to find William and bump into the porn director that’s on the run, the Korean character and Hong Kongese character could start a nightlife business.” I’m anticipating the spin-off version of Come and Go. I’m also interested in Kah Wai’s collaboration on “Sumimasu Asia Geinnin.” This a project by Yoshimoto Creative Agency, which is the agency Seiji Chihara is signed to.

One last thing. At first, I didn’t think the two had any connection to each other, but it turns out that they’re long-time friends. Fujimoto has even worked on-set with Kah Wai before. For more details, go to TIFF’s official YouTube channel and watch 『カム・アンド・ゴー』リム・カーワイ監督x『海辺の彼女たち』藤元明緒監督 スペシャル対談 TIFF Studio 第67回 (A Special Talk Session between Lim Kah Wai (Come and Go) x Akio Fujimoto (Along the Sea)/67th TIFF Studio). Watching the two reunite at TIFF made me think about Kah Wai’s trilogy, and I felt a warm feeling in my heart.

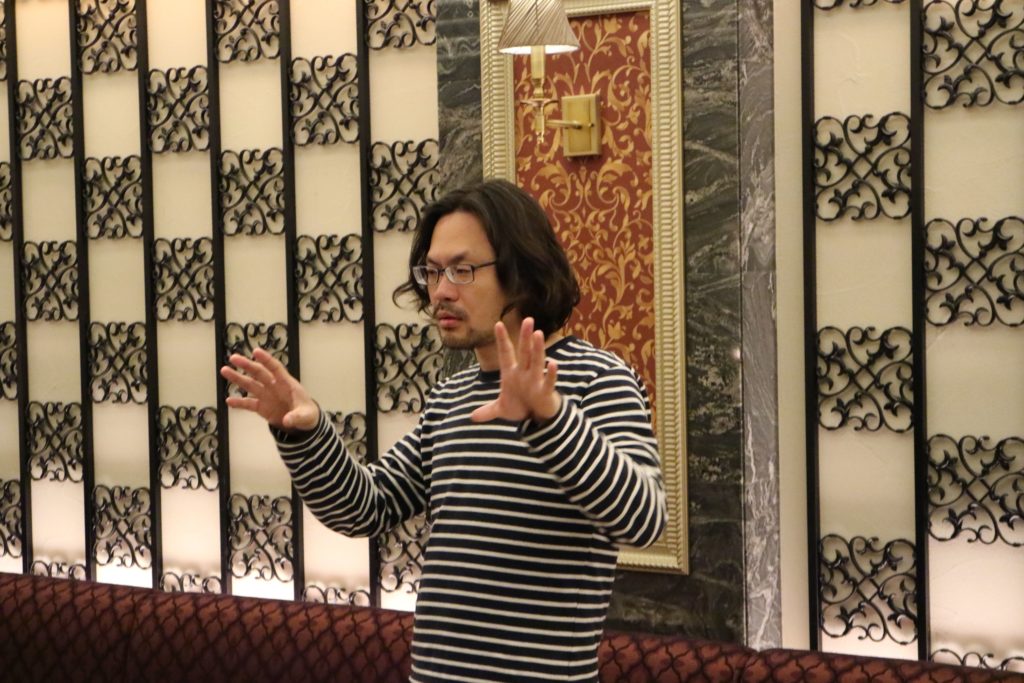

Akio Fujimoto

Akio Fujimoto is a film director and was born in Osaka in 1988. After studying psychology and sociology of the family in university, he enrolled in Visual Arts College Osaka. While Fujimoto was still a student, he worked on-set for Lim Kah Wai’s film, The New World (2011). After graduating, he created his debut feature-length film, Passage of Life (2018), and won The Best Asian Future Film Award and The Spirit of Asia Award by the Japan Foundation Asia Center at the 30th Tokyo International Film Festival. He then directed the short film, Bleached Bones Avenue (2020), which was screened at Osaka Asian Film Festival and Along the Sea (2020). He’s currently based in Myanmar and takes on the theme of migrants.

https://twitter.com/akio_fujimoto

Lim Kah Wai

Lim Kah Wai is a self-proclaimed “cinematic drifter” born in Malaysia in 1973. He graduated from the Graduate School of Engineering Science at Osaka University. After graduating, he worked in telecommunications, but then enrolled in the Department of Directing at Beijing Film Academy. In 2010, he independently directed and produced After All These Years post-graduation and made his debut. He then directed Magic & Loss (2010) in Hong Kong, The New World (2011) in Osaka, and Fly Me to Minami (2013). After directing the commercial film, Love in Late Autumn (2016), which was shown nationwide in China, he directed No Where, Now Here (2018) and Somewhen, Somewhere (2019). He continues to create films, drifting to various corners of the world.

https://twitter.com/cinemadrifter

Pictures provided Tokyo International Film Festival

Translation Lena-Grace Suda