From business to science, the number of situations where people advocate for the necessity of art is dramatically increasing. Although the world doesn’t look different under the influence of the corona pandemic, people’s minds are changing; under such change, how does everyone’s perception of art transform? Gallerists, artists, and collectors are now researching and trying to predict what kind of art will appear in the post-corona generation.

In the third volume of this series, we interview critic/curator Mika Maruyama and artist/actor Mai Endo, the duo behind Japanese queer art zine, Multiple Spirits.

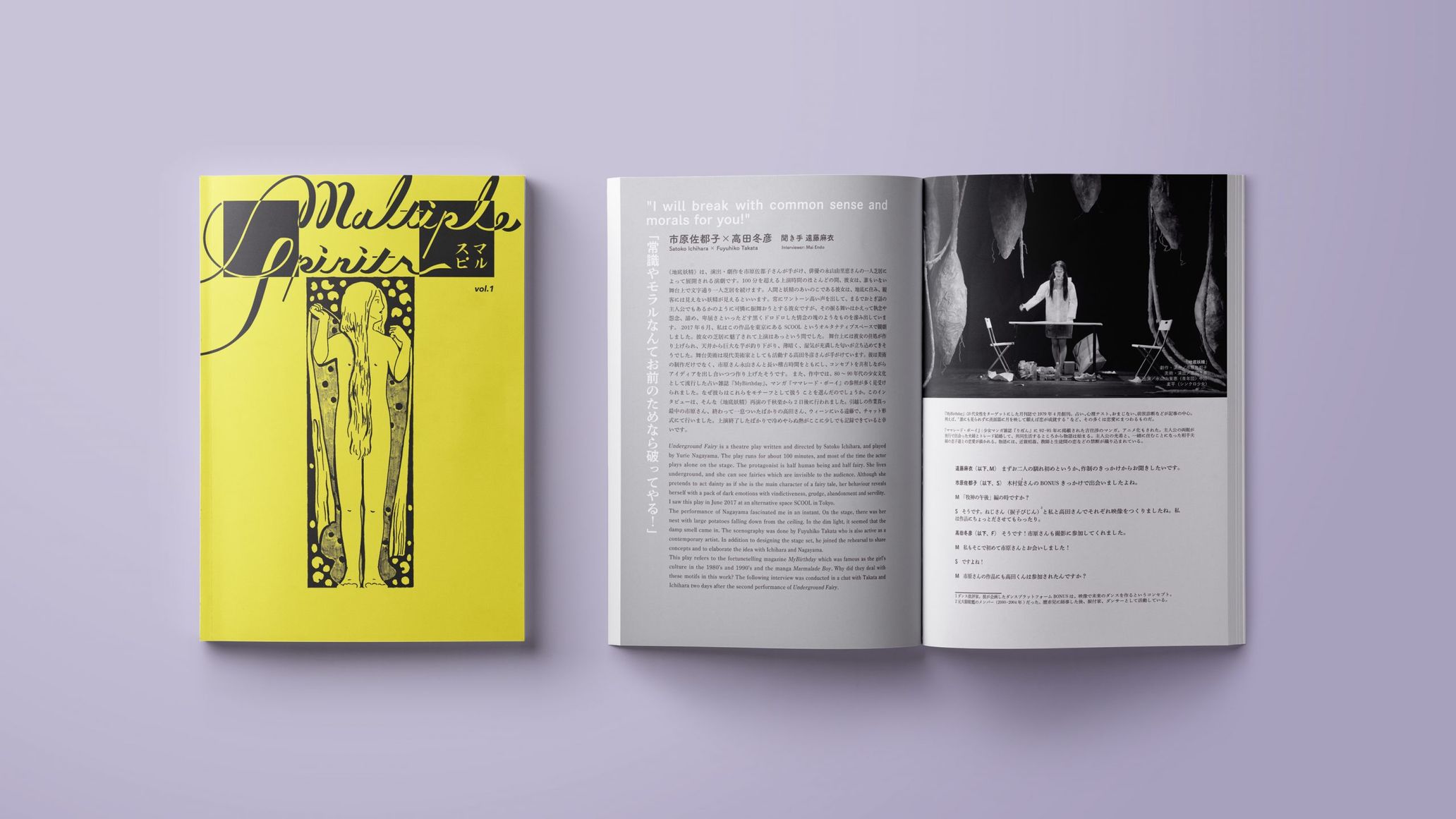

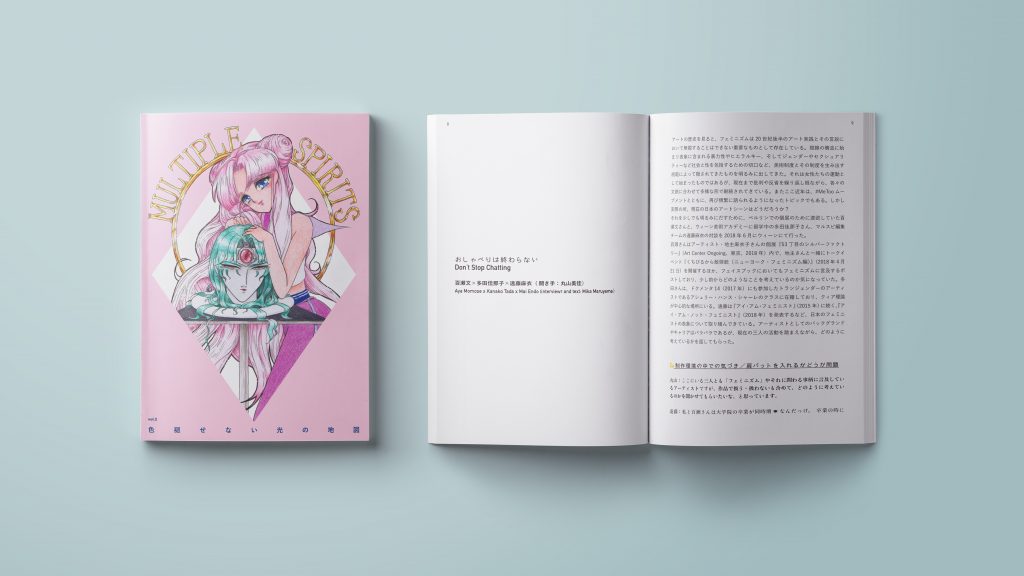

“In the beginning, woman was the sun.” These were the words written in 1911 by Hiratsuka Raicho in the first issue of Seito [Bluestocking], Japan’s first all-women literary magazine. Since then, over a century has passed. In 2018, the first issue of Multiple Spirits, the “queer art zine from/within Japan,” appropriated the cover of Seito’s first issue.

In recent years, Japan has seen an increasing interest in issues concerning gender and sexuality in response to the fourth-wave feminism that is sweeping the world. Nearly every week, new essays and academic books on related topics line the shelves of bookstores, and the number of dramas and movies depicting sexual minorities has increased to a level unimaginable ten years ago.

Meanwhile, how about the art world? The 2019 Aichi Triennale made an affirmative action plan to include an equal number of male and female artists in an effort to promote gender equality and was met with substantial backlash.

Multiple Spirits’ name comes from the multiple ways of thinking, and it was under these circumstances that the first issue was launched. Started by Mika Maruyama and Mai Endo, the two printed the first issue using a home printer, binding the pages themselves using a stapler.

The zine currently has two issues out. Inside the zine, one can find content that weaves together hard and soft topics, including interviews with artists working domestically and abroad, translations of discourse around feminism in the communist bloc and the Anthropocene, and conversations in the form of casual chats.

What kind of concerns did Multiple Spirits emerge from? Why are they “a queer art zine from/within Japan?” Their background story includes encounters with overseas feminism/queer theory and concerns about the discourse that has dominated Japan’s art world since the “gender dispute.”

――Why did you decide to start Multiple Spirits?

Mika Maruyama: This is my sixth year living in Vienna, so it all started when Mai [Endo] came to Vienna to study abroad. We weren’t particularly close at the time, but I knew she made work around feminist themes, so I introduced her to Marina Gržinić, a professor at my school, the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. She’s a philosopher from Slovenia who’s also active as an artist, and her class was a really open place where artists, researchers, and activists all came together for discussions.

Mai Endo: A bit before I studied abroad in Vienna, I presented a work called “I Am Not a Feminist!” at Festival/Tokyo 17, in which I signed a marriage contract with my then-husband and carried out a wedding ceremony at a performing arts festival. But right after that, we got divorced for personal reasons unrelated to that piece. My work and life had become so connected that I lost sight of what kind of work to make and what kind of life to live going forward. And that was when I decided to go to Vienna.

Mika: So I listened to her troubles about that, and we started opening up to each other. Since coming to Vienna, I’ve been growing particularly interested in work that crosses queer theory and media theory, but I couldn’t help but feel a gap between what’s being said in Japanese and what’s being discussed in Vienna. I wanted to create a space to have those kinds of discussions in Japanese through art. But I couldn’t do it alone. While listening to Mai’s troubles, I felt like although our work was different, we had a shared awareness of issues, so it started when I asked her, “Want to make a zine?”

Mai: We hit it off over drinks, like, “That sounds great!” At that time in 2018, art wasn’t as talked about in Japanese in the context of feminism and queerness as it is now, so we were also motivated to find language that aligned with our reality.

――What kind of school is the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna?

Mika: It’s an art school, but it places importance on theory as well as practice, so there’s quite a lot of gender and queer theory. Everyone is familiar with these theories, so even if you’re an artist, you can seek out discussions, and there’s a lot of art that deals with gender and sexuality. Also, there are a lot of people staying in Austria under different statuses whether they’re immigrants, refugees, or international students, so even when I say gender and queerness, there’s still the difficulty of having discussions within different contexts.

Mai: I was on Tokyo University of the Arts’ exchange program, but Geidai [Tokyo University of the Arts] has an overwhelmingly large proportion of male professors. The Academy is completely the opposite, and about 80%, from the professors to the staff, are non-male. In relation to my work, people around me often asked what I thought about gender and sexuality, and how it was discussed in Japan. But I’d never been asked to give an opinion about Japanese society through my work before, so I felt frustrated at myself for only being able to respond with clichés like, “There still isn’t enough discourse in Japanese art,” or “I’ve internalized the situation in Japan.” Also, Marina said that universities are open to all people who seek knowledge, so even you weren’t her student, or weren’t a student at all, anyone who wanted to participate was welcome to come whenever they wanted. That was so cool of her. Every day, all kinds of people were coming and going.

――Why do you declare that you’re “from/within Japan” in your statement?

Mika: There’s no question that we grew up in Japanese culture, particularly the girls’ culture of the 90s. So first off, we thought we couldn’t ignore the influence of that culture when talking about art and gender. Girls’ culture is a connection point to queer culture, too. Also, we wanted to emphasize the kind of soil our knowledge grows from. I think there’s no such thing as universal knowledge. I’ve been influenced by and admire the history and practices of black feminism and Latin American feminism, which have taken creating language into their own hands. So it’s not about disseminating Japanese culture, but about us wanting to construct our own language as Japanese speakers. Of course, that comes from the fact that we view Japan’s patriarchal discourse as problematic.

Also, there’s the problem of translation; Multiple Spirits is bilingual in Japanese and English, so we have non-Japanese speakers in mind, too. As people raised in Japan, we’ve been forced to confront Japaneseness on many different levels upon going abroad and being exposed to foreign cultures. For example, when we think about gender and sexuality, we can’t ignore Japanese imperialism, colonialism, and racism. You can’t just be a neutral person, and there are so many situations where I have to be aware of the cultural breeding ground of Japan. So I’d like to create a space to connect art and language that includes that perspective.

――In your statement, you write, “We belong to the historical flow of feminism.”

Mika: When it comes to gender and sexuality, many barriers couldn’t have been broken without the efforts of our predecessors, and we think it’s the same for the queer community. In the context of Japan, even the art world in the 90s often featured feminism and gender-related themes. There were exhibitions and active discourse, too.

Photography Claudia Sandoval Romero

©Claudia Sandoval Romero

――What was that like?

Mika: In the 90s, researchers, such as Kaori Chino and Midori Wakakuwa founded The Image and Gender Research Association. Artist and researcher Yoshiko Shimada, who’s still active today, brought up gender issues while linking them back to imperialism, and Yuko Hasegawa curated the exhibition, De-Genderism detruire dit-elle/il (1997). Performance artist Tari Ito established Women’s Art Network and Dumb Type presented S/N during this period, too.

Mai: In 1991, a special exhibition by Michiko Kasahara* at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography was apparently the first art exhibition held in a Japanese art museum from the perspective of gender and feminism. According to Kasahara, there’d been a phobia against feminism in Japan until then. I think it was a period where a lot of perspectives that’d been lacking started to grow.

*From 1989, Michiko Kasahara was an art curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, where she organized many exhibitions. Currently, she is the Vice Director of the Artizon Museum.

Mika: It was a really active time for gender and sexuality issues in the arts. But as we entered the 2000s, that disappeared. One of those causes is called the “gender dispute,” where critics in Japan’s art world said that because feminism was an imported concept, Japan didn’t need it, and that caused discourse to die out. Also, there was a big backlash from Japanese society overall against feminism. We’re from the generation below that, but I felt uncomfortable that not only did we not talk about gender issues, but even when I talked with female artists, their work was lumped together from a male-centric perspective with phrases like, “female-specific” and “representations of femininity.” There’s actually a wide variety of things that lie behind what people have hidden with the word “femininity.”

――People only have a rough understanding, so they can only express themselves with rudimentary vocabulary.

Mika: I felt like the words didn’t exist. That’s why earlier, I said we have to construct language—because we also wanted to know what’s hidden behind the word “femininity.”

――I see.

Mika: For example, Mai and I have thought about how the discourse and the work of female artists is different in a photography world with Michiko Kasahara versus what it would be without someone like that. Just as Yurie Nagashima wrote in “’Bokura’ no ‘onnanoko shashin’ kara watashitachi no girly photo e,” (2020) the photography world in the 1990s was male-dominated. Yet, I think there’s a side to it where curators like Kasahara have allowed artists like Nagashima and Yuki Onodera to be on the front lines with their work. On the other hand, there are very few female artists who are active in Japanese contemporary art.

――Just one person can make a big difference.

Mika: Kasahara is an expert in gender theory, and I think it was big that she created discourse as a curator at a photography museum by connecting feminism and gender to photos. We’re able to access that discourse and art practice because of her too.

――Is there anything you feel as a creator, Mai?

Mai: I feel like in these past few years, creators’ awareness and ways of thinking have changed at a really rapid rate. Also, they’re not only making the themes around gender and sexuality, but also thinking of the form, structure, and creation process itself more radically. For example, curator Junya Utsumi, who contributed to the second issue of Multiple Spirits started a concept called “Feminism Curation,” criticizing the male-centric and monolithic framework of exhibitions themselves. Also, critics Takumi Fukuo and So Kurosaki said that they questioned the masculine narrative of critiques, so they were interested in the use of the “chat” format in the second issue of Multiple Spirits.

Mika: We also want to encounter, share, and learn more about that kind of expressive work. The reason why we deal with girls’ culture head-on is because we were influenced by the collaboration between Satoko Ichihara and Fuyuhiko Takada and their respective practices, and the reason why we dare to emphasize “chatting” is because Aya Momose and Maiko Jinushi’s work exists. Miwa Negoro, a curator who translates with me, is also aware of the suppressed discourse, and I think that’s why we share the understanding that we need to talk about it in the form of artistic expression or discourse, regardless of the method. I think that has something to do with the fact that art collectives are becoming more active now. There were connections across fields like that in the 90s too, and I think that created a big flow. Especially because it’s disappeared, it’s like we want to do what’s been repressed in a different form.

Mai: That’s true. At the time of the gender dispute, the criticisms that came up when more exhibitions started dealing with feminism and gender were that feminism is a “borrowed ideology or understanding,” and wasn’t based on reality, and of course, Multiple Spirits takes into account the logic of the side that made those criticisms. Having said that, I think the old binary of Japan versus the West is already invalid, and I want to talk about more things we can share transnationally. In that regard, the fact that we have two locations, with me in Japan and Mika in Vienna, makes things very open.

Mika: When I first came to Vienna, it made me realize that the conversation around art and gender in Japan hadn’t been updated since the 90s. Even my teacher told me, “First, you need to update your way of thinking.” Although gender theory stopped being discussed all that much in Japan, the intersectionality between feminism and queerness has developed, and feminism by people of color and new discourses from South America and Southeast Asia have been created, right? This is true in the field of art, too. In Japan, even though all kinds of activities continue, I think people talk about gender issues as if they’re a thing of the past.

――So the discourse in Japan hasn’t been updated since the gender dispute?

Mika: Since the Aichi Triennale, I think there’ve been more works and discussions around gender in Japan than before, but I also see some of the same discussions from the past being repeated. Of course, it’s a change we should welcome, but I also wonder why it’s coming from a perspective that only takes up gender as an issue. At Multiple Spirits, we think intersectionality is important, and we think it’s important how different issues relate and intersect. We believe that because of our understanding that we are standing in the history of feminist and queer communities up to this point. Also, rather than repeat the same things, we want to use the potential we have today and think about what we’re experiencing, and we want to know how other people are thinking, too.

――What do you want to do going forward?

Mai: Multiple Spirits is bilingual in Japanese and English, but we also want to have a cultural exchange with non-English speakers, and we want to research the cultural exchange that’s already happened. We don’t want language to become a barrier. In 2019, we went to Seoul and met and talked with artists directly, went to see local exhibitions on feminism and queerness, and got acupuncture and moxibustion done. In the future, I’d like to engage with whatever I’m interested in, regardless of the genre.

Mika: Multiple Spirits has given me more opportunities for meetings and exchanges. In particular, I’d like to take good care of my connections in East Asia, like Korea and China. Also, I’m interested in the cessation of the discussions that took place in the 90s in Japan, so I’d like to connect with people who were involved in that kind of work. And, I’d like to hurry up and release issue 3. We’re both trying to finish our PhDs, so we haven’t been able to start the final edit…but we make it a rule not to overdo it.

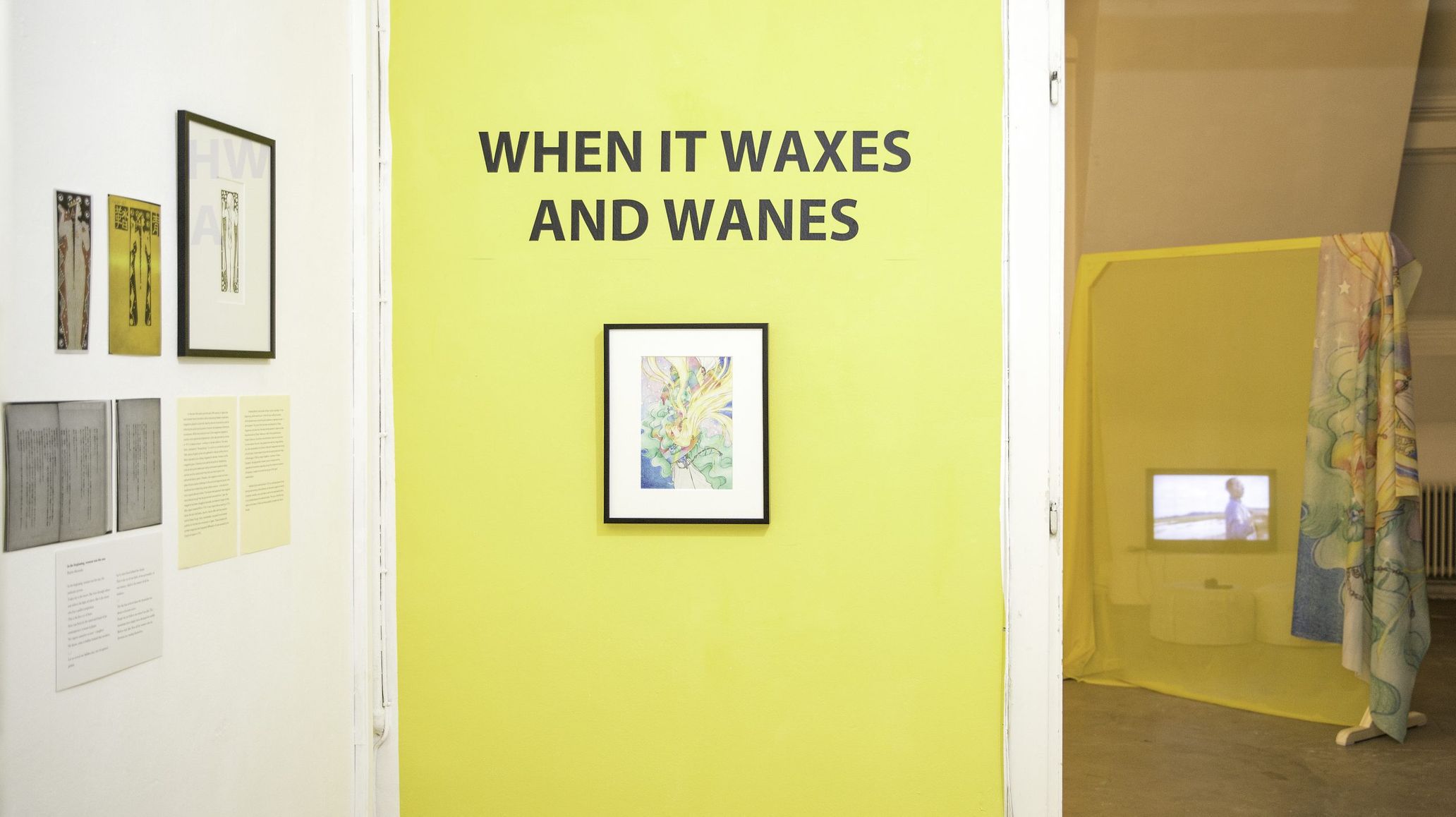

Mika Maruyama

Born in Nagano Prefecture, Mika Maruyama is a curator and critic based in Vienna and Tokyo. She holds a master’s degree in philosophy from Yokohama Graduate School of Culture, the Graduate School of Yokohama National University, Japan, and is currently a doctoral student at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. The exhibitions she has curated include “When It Waxes and Wanes” (Vienna, 2020), “Protocols of Together” (Vienna, 2019), “Behind the Terrain” (Yogyakarta, 2016/Hanoi, 2017/Tokyo, 2018), and “Body Electric,” (Tokyo, 2017). She is also a contributing writer at publications including “Artscape,” (Bijitsu Techo) “Camera Austria,” and “Flash Art. http://www.mika-maruyama.com/

Mai Endo

Mai Endo was born in Hyogo Prefecture. She is currently completing a Doctoral Program in Fine Arts at Tokyo University of the Arts. She is an artist and actress who combines media and methodologies such as video, photography, and theater. Her expression playfully overlaps the message of the body in the here and now and the gap between social norms and art forms. Her main recent exhibitions include “Kanojotachi wa utau” (The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts, 2020), “New Crystal Palace” (Talion Gallery, Tokyo, 2020), and “When It Waxes and Wanes” (Vienna, 2020). Her solo exhibitions include “I Am Not a Feminist!” (Goethe-Institut Tokyo, 2017)

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)