Photography Edward M. Gómez

Genuine art brut artists create their works because they must create.

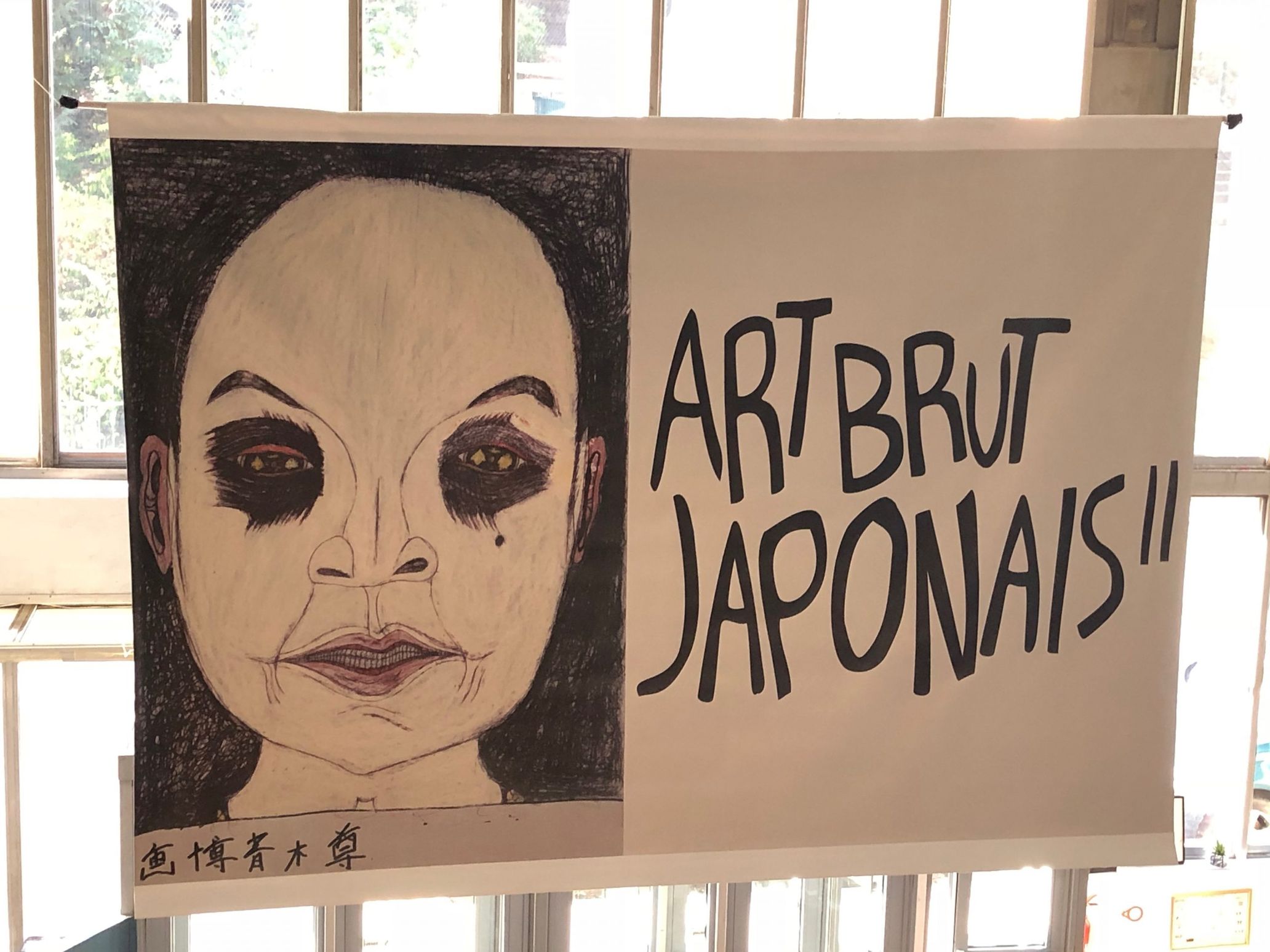

Since the early 2000s, when art dealers in the United States and Europe first became aware of the phenomenon that would soon become known as “Japanese art brut,” unusual paintings, drawings, sculptures, and mixed-media works in this special category have earned admiration from collectors and critics overseas.

Today, the term “Japanese art brut” evokes historical ties to the category of hard-to-classify works of art that the French modern artist Jean Dubuffet established in the 1940s. Nowadays, this label also connotes certain characteristics that have become closely associated with works made by contemporary self-taught artists in Japan. These characteristics include very skillful, inventive ways of using materials: paint or ink on paper, clay, collaged paper, or handwoven fabric.

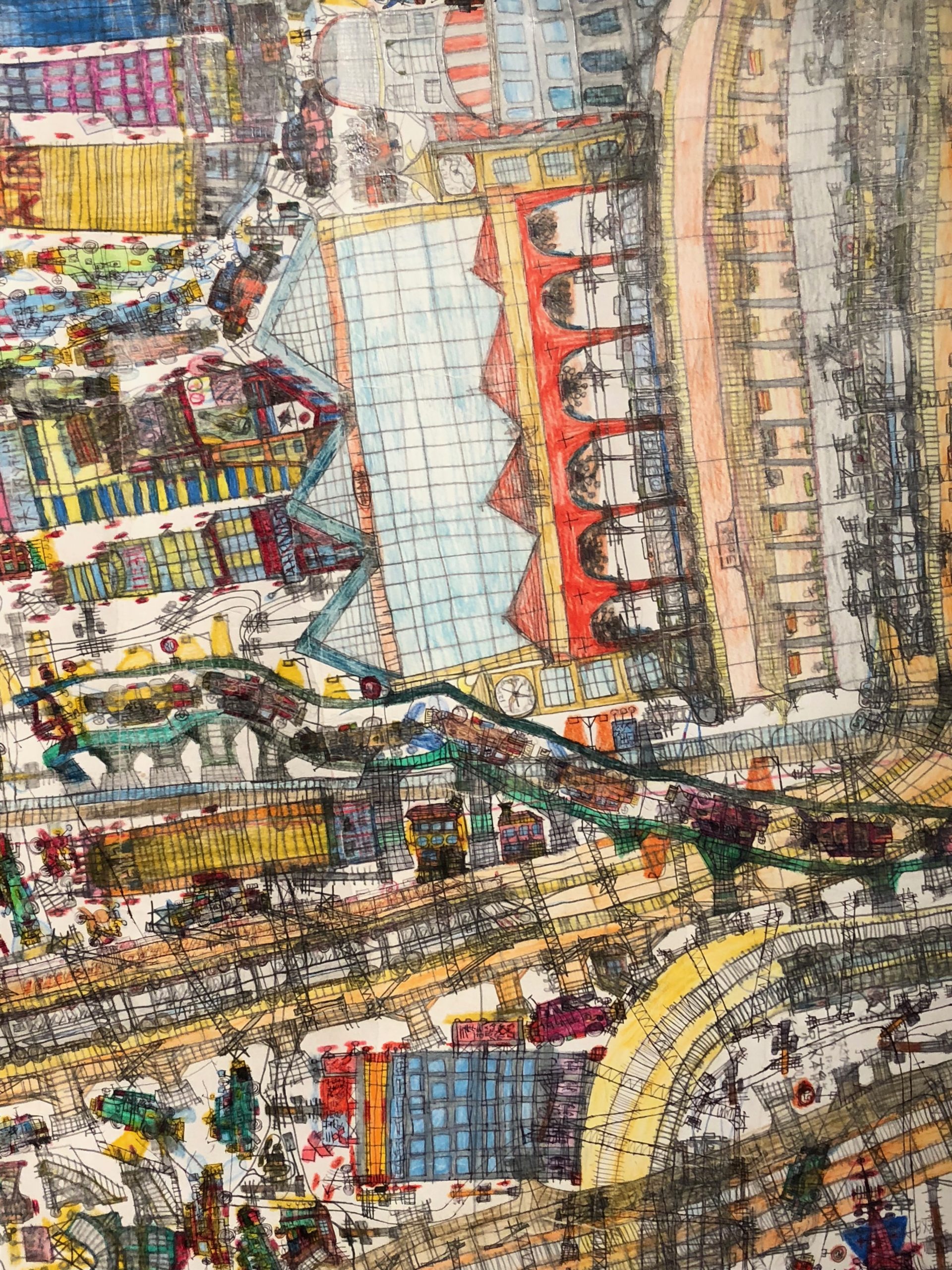

Japanese art brut artists’ works are also recognized for their ambitious subject matter (such as Norimitsu Kokubo’s large, aerial drawings of cities) or their unusual forms (such as Shinichi Sawada’s spike-covered, fired-clay monsters). Some of these works of art display an emotionally and psychologically obsessive quality. As a result, they feel irresistible and compelling. (One of Kokubo’s drawings, made with pencil, colored pencil, markers, and watercolor on paper, covered an entire wall in the Art Brut Japonais exhibition at Halle Saint Pierre, in Paris, in 2018.)

Photography Edward M. Gómez

As I noted in the first part of this two-part article, more than 70 years ago, when Dubuffet developed a definition of what he called “art brut” in French (a term that means “raw art”), he explained that this label applied to paintings, drawings, and different kinds of objects made by people who live on the margins of mainstream society and culture. These self-taught art-makers do not go to art school. Usually, they are not familiar with the movements and critical debates that are important elements of mainstream art history.

In fact, most of the people who created the objects Dubuffet collected did not regard themselves as artists. For them, the academic or intellectual notion of “art” did not exist or was not relevant to their lives.

When I present lectures about the history of art brut and outsider art, I mention that there is a big distinction between such self-taught artists and artists who have been trained in art schools and create their works primarily for sale in the mainstream art market.

I point out that genuine art brut or outsider artists do not make their art because they want to make it. Instead, they create their art because they must create it. For these artists, making their art is as necessary as breathing air. Making their art is a matter of personal survival, not a matter of choice. These artists feel an urgent need to create.

This tendency can be felt in many of the remarkable works that have been created by Japanese self-taught artists associated with so-called Japanese art brut.

Foreign collectors’ demand for this art keeps on growing

As noted above, some distinctive characteristics can be found among the work of these Japanese creators.

Those who make drawings often fill every square centimeter of their pictorial space — the visible, two-dimensional space in which they create their compositions. Keiko Abe uses gel pens to fill her drawing-paper sheets with rows of flowers, human figures, and multicolored grids. Her works feel lively, and Abe appears to find joy in everyday subjects. Yuichiro Ukai, an artist who is a member of Atelier Yamanami, an art studio for disabled people in Shiga Prefecture, has attracted an enthusiastic audience for his drawings in the United States and Europe.

Photography courtesy of Atelier Yamanami

Photography Koji Nishikawa, courtesy of Saitama Prefectural Museum of Modern Art

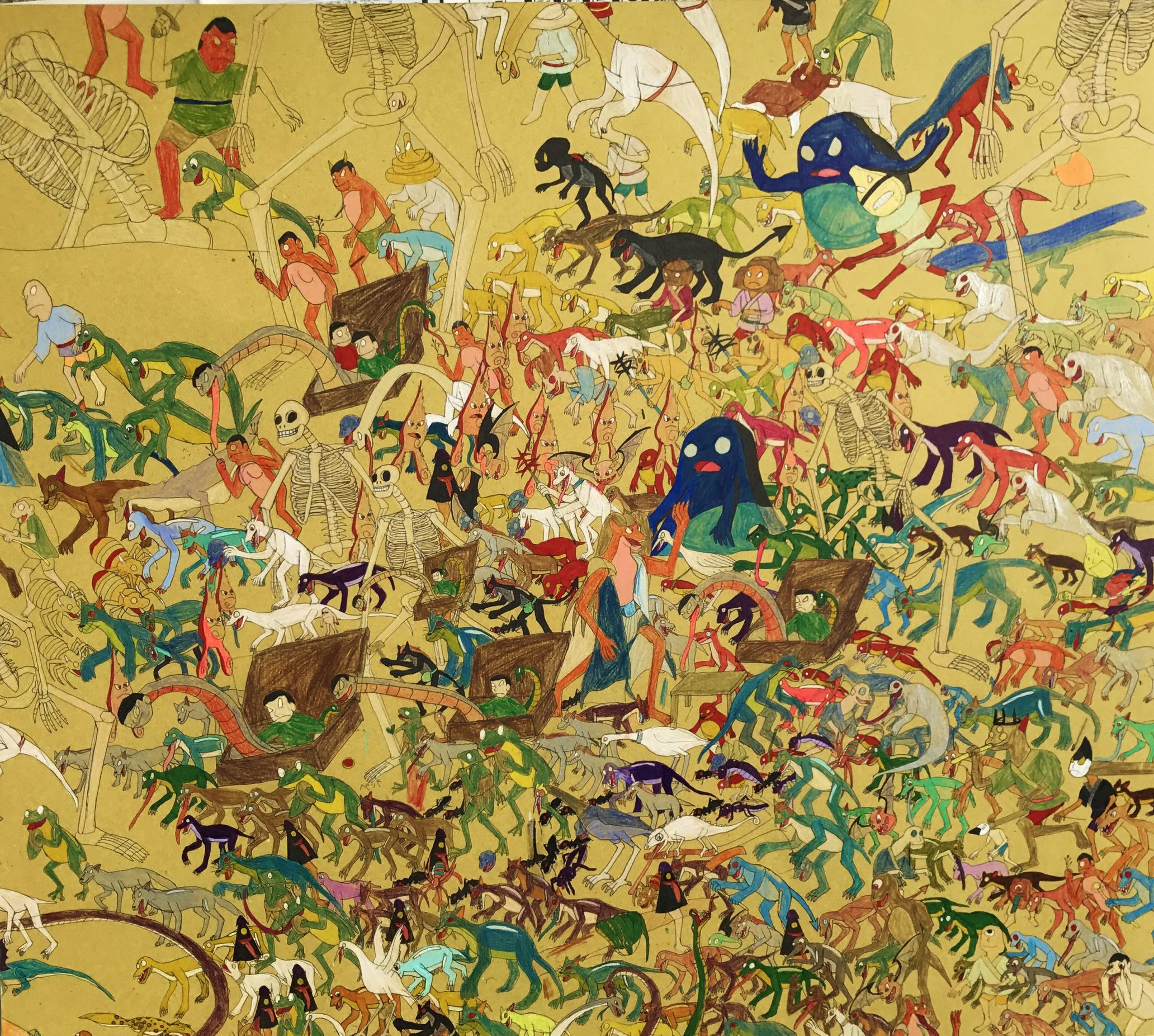

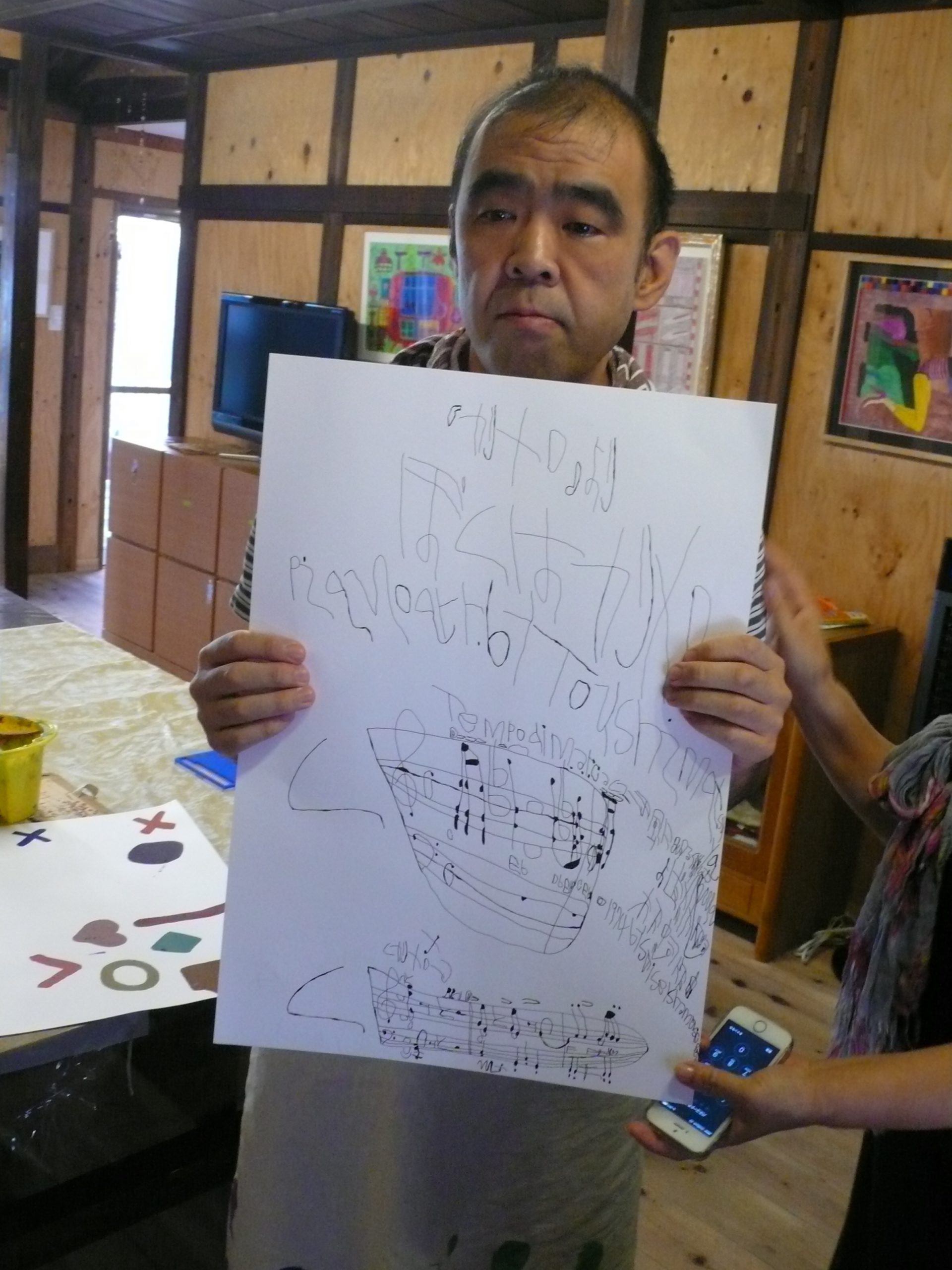

At the annual Outsider Art Fair in New York, the Tokyo-based art dealer Yukiko Koide has had great success presenting Ukai’s works to foreign collectors. His compositions are packed with dinosaurs, Japanese and foreign figures in historical costumes, giant insects, ancient sailing ships, monsters, and robots.

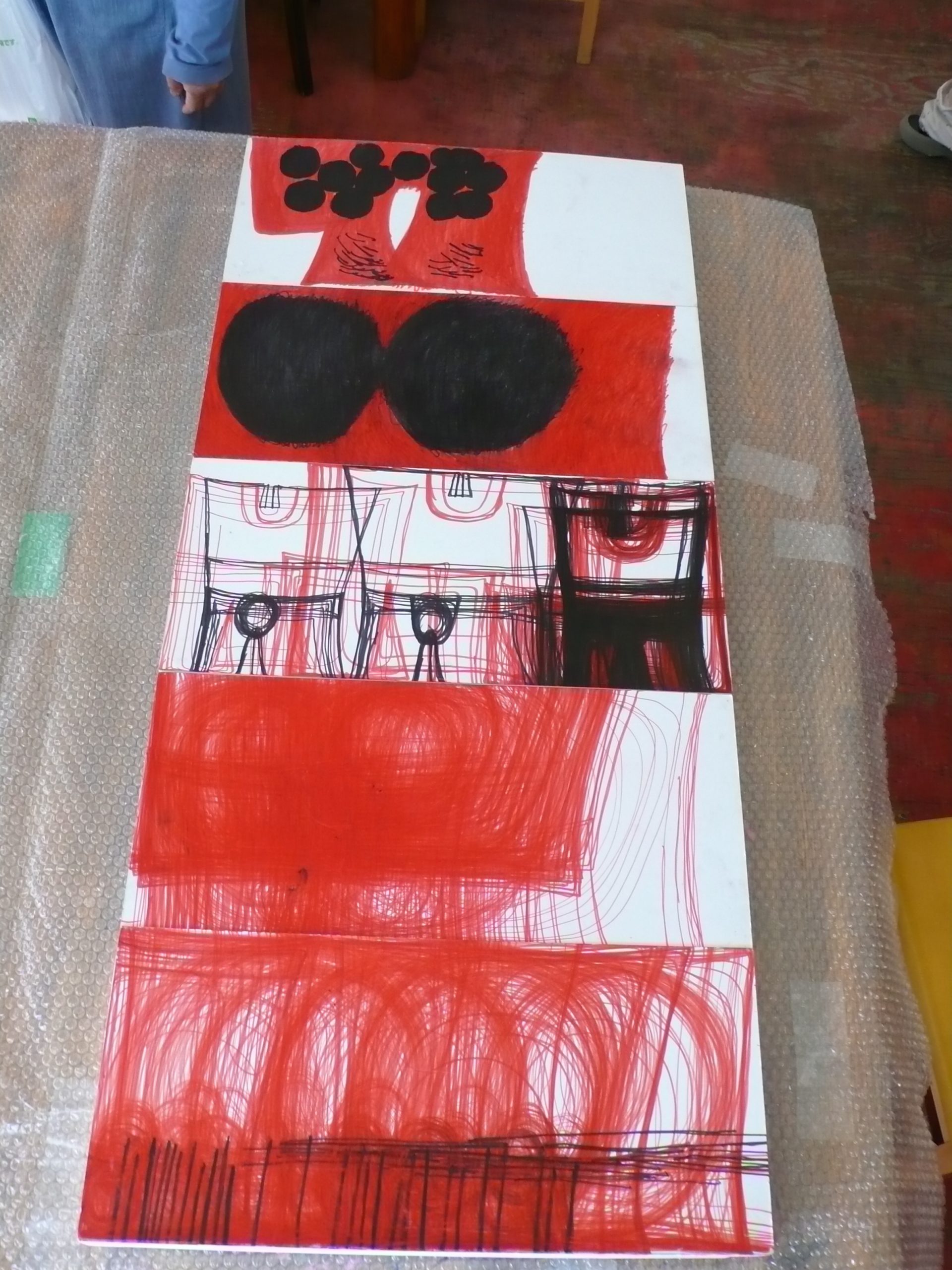

In their works, Japan’s art brut creators often interpret their subjects, even if their art is abstract. (After all, the subject of abstract art is the nature and expressive potential of art itself.) Examples of such abstract works include Akiko Yokoyama’s drawings in a simple, powerful palette of black, white, and red marker ink on paper. (In the exhibition Art Brut from Japan, Another Look, which I curated for the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, I included a group of Yokoyama’s bold drawings. That exhibition opened in November 2018 and ran through April 2019.) Yokoyama is associated with Kobo Shu, an art workshop for disabled people in the city of Kawaguchi, in Saitama Prefecture, north of Tokyo.

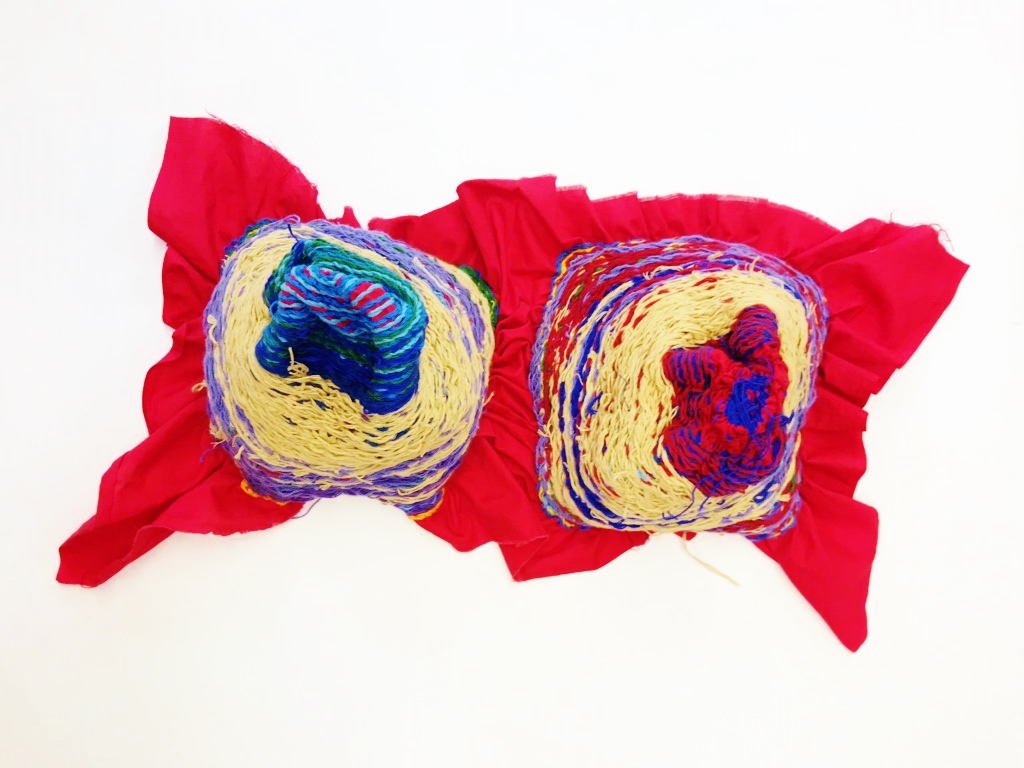

Momoko Nakagawa, who was born in 1996, is another young, female artist who creates colorful abstract drawings on paper. Using ballpoint pens and markers, she produces dynamic webs of thin black or colored lines. Her compositions resemble engineering drawings for avant-garde buildings. Yumiko Kawai, another artist associated with Atelier Yamanami, uses cotton fabric and embroidery thread to make mysterious, three-dimensional works resembling breasts or unknown organic growths. At the same art workshop, Momoka Imura also creates unusual fabric works. Using soft, brightly colored cloth, Imura makes round blobs that she covers with plastic buttons. These strange objects feel very odd and also charming at the same time.

Photography Edward M. Gómez

Photography courtesy of Atelier Yamanami

Photography courtesy of Atelier Yamanami

Photography courtesy of Yukiko Koide Presents, Tokyo

Photography Edward M. Gómez

The artist Takuya Tamura has created a distinctive method of depicting his subjects in silhouette. He uses bold marker colors to make grids shaped like men, women, animals, or other subjects. Despite the regularity of this technique, in Tamura’s hands, it is very expressive.

Photography courtesy of Atelier Yamanami

Three more artists who produce highly original works of art brut include Koji Nishioka, Fumiko Okura, and Kazumi Kamae. Nishioka is associated with Atelier Corners in Osaka, where he makes drawings of musical scores whose written notes and horizontal lines he distorts and transforms into rhythmic, abstract compositions.

Photography Edward M. Gómez

Okura makes her mixed-media collage works at Kobo Shu. She cuts photographs of female faces from magazines and often photocopies them. She writes names and words repeatedly on small pieces of paper and then uses clear tape to join together all of these elements into irregularly shaped objects. These unusual objects appear to be two-dimensional compositions and three-dimensional sculptures at the same time.

Photography Edward M. Gómez

Also at Atelier Yamanami, the ceramics artist Kamae makes sculptural figures with two or more faces and titles that often refer to the director of the workshop. Her sculptures’ roughly textured surfaces, undulating forms, and ambiguous expressions are their hallmarks.

Photography courtesy of Atelier Yamanami

Works like these have been shown in gallery and museum exhibitions in Japan and Europe. They have been presented for sale at the Outsider Art Fair in New York and at only a few galleries in the United States. But the demand for these works from overseas collectors is increasing. In New York, Venus Over Manhattan, one of the city’s newest contemporary-art galleries, recently presented a solo exhibition of the ceramic sculptures of the Japanese art brut artist Shinichi Sawada. A review of this exhibition in the New York Times noted that, with their little horns, claws, and spike-covered bodies, Sawada’s creatures remind viewers of “imagery from Japanese mythology and medieval bestiaries.”

In order for Japanese art brut to flourish overseas, the cooperation of existing galleries is necessary

Jennifer Lauren Gallery in England and Cavin-Morris Gallery in New York regularly show works made by Japanese art brut artists, and in Lausanne, Switzerland, Galerie du Marché has sold works by the artist Itsuo Kobayashi. Kobayashi lives in Saitama, where, for more than 30 years, he has filled notebooks with detailed, illustrated descriptions of every meal he has eaten, including take-out food from convenience stores. These works became very popular when they were shown in the Swiss museum’s exhibition in 2018-2019.

The Japanese art dealer Nobumasa Kushino, a leading researcher in the art brut and outsider art fields in Japan, brought Kobayashi’s colorful, illustrated books to my attention. Until recently, Kushino had his own gallery in Fukuyama, in Hiroshima Prefecture. Now he works for the arts council in Shizuoka. In recent years, Kushino has written and published several books about his outsider art discoveries, including Yankee Anthropology: The “Art” and Expressions of Breakthrough People (Film Art, Inc., 2014) and Living on the Outside (Taba Books, 2017). (These books were published in Japanese.)

In order for more of the work of Japanese art brut artists to reach collectors overseas, more foreign art dealers must gain access to it from its sources in Japan. Or they must collaborate with galleries in Japan that already represent some of these artists. However, for most foreign art dealers, there is a language barrier when it comes to communicating effectively with business colleagues in Japan. Even though English is the most common language in the international art world, it helps to be able to communicate more precisely in Japanese with contacts in Japan.

Foreign art dealers should also keep in mind that many Japanese self-taught artists and their families or guardians, or the social-welfare organizations with which they are associated, like to move slowly in developing relationships with potential foreign representatives. Many of these artists are newcomers to the international art market. Many foreign art dealers have never had any direct business experience with Japanese institutions.

In Tokyo, Shino Sugimoto and Hanayo Haginaka run ACM Gallery, which is located near Ebisu Station. (This gallery’s name is an abbreviation of “Arts and Creative Mind Association.”) Sugimoto and Haginaka show the work of numerous self-taught artists, including Hironobu Matsumoto, who makes large-scale, semi-abstract maps of the world, and Miruka, a young woman in Osaka who makes drawings of birds. Both of these artists use colored pencils and inks on paper.

In an e-mail interview, Sugimoto and Haginaka wrote, “Compared to Europe and the United States, the art market in Japan is small. It is difficult for galleries to sell not only outsider art but also art in any other field.” These art dealers mentioned that, in Japan, most collectors of contemporary art are not familiar with the history of art brut and outsider art. They do not recognize the value of self-taught artists’ work in relation to modern-art and contemporary-art history. As a result, these collectors cannot accurately estimate the investment value of self-taught artists’ works.

Sugimoto and Haginaka explained that the public’s and the art market’s understanding of the value of the work of talented self-taught artists would increase if museums paid more attention to the art brut and outsider art fields. They noted that they believe the public would like to see more diverse forms of art presented in museums — and even that the functions of museums need to be reconsidered and revised.

They wrote, “For example, it would be great if museums could become places that promote social well-being and what is good for society.”

Photography Edward M. Gómez

Within Japan, active interest in art brut is rapidly developing

In recent years, the Shiga Prefectural Museum of Modern Art in Otsu has been developing a significant collection of art brut. It has presented high-quality exhibitions of this kind of art and published some notable catalogs looking at the history of self-taught artists’ creativity in Japan. Shiga Prefecture is well known for its ceramic-making traditions, so it is not surprising that many art brut artists, such as Shinichi Sawada or Kazumi Kamae, who have become known for their innovative, fired-clay sculptures, come from and live in this region.

Tsukasa Ikegami, the chief curator at the museum in Shiga, recently noted in a written interview that, in Japan, museums are “searching for the language and ways of looking” to use to describe groups of artworks that “cannot be perfectly explained by modern-art theory alone.” He noted that museums must strive to accomplish this task in relation to their existing collections of modern art.

With regard to looking at, presenting, and understanding the work of art brut and outsider artists, Ikegami observed, “First of all, basic research about works of art and artists cannot be overlooked. The greater the increase in the number of curators and researchers who are interested in art brut, and of institutions that collect this kind of art, the more complete this basic research will become.”

From the point of view of Europe and North America (the territories in which the related art-collecting and art-research categories of art brut and outsider art were born), the emergence of serious interest in this kind of art in Japan has dramatically broadened the art brut field. Strong, common technical and stylistic characteristics that are visible in the works of many self-taught artists in Japan have reinforced the notion of “Japanese art brut” as a distinctive phenomenon within the broader history of art brut and outsider art.

Yutaka Miyawaki, the director of Galerie Miyawaki in Kyoto, whom we met in the first part of this article, has had many years of experience promoting and presenting art brut works of the highest quality from Europe and Japan. In a recent interview, he said, “In Japan, we should appreciate the extraordinary creative energy of this kind of art and the artists who make it. Such understanding will help reinforce the value of art brut.”

Miyawaki is a great admirer of what he calls art brut’s “radical spirit.”

He said, “The artists who make this work really are not ‘outsiders.’ Instead, what they create offers a counterbalance to more conventional, boring, fashionable art. We should be fascinated by this aspect of art brut.”