In recent years, the category of art made by self-taught artists that is known in Europe as “art brut” and more commonly in the United States as “outsider art” has also become known in Japan, where the phenomenon of so-called Japanese art brut has emerged. What is this kind of art and what is its status in the broader world of art and culture in Japan today?

In Europe, the deeper roots of this kind of art can be traced back a few centuries, but its modern history as a field of research and collecting began around the middle of the 20th century. It was in the 1940s that the French modern artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) coined the term “art brut” after doing pioneering research in France, Switzerland, and Germany.

Photography Jean-Jacques Laeser, Archives de la Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

The French term “art brut” means “raw art.” It is used to describe works of art made by people who live on the margins of mainstream culture and society. These art-makers do not go to art schools to study art history or the familiar techniques and materials that are used by so-called professional artists to make art. Instead, art brut creators are completely self-taught. Often, to make their art, these autodidacts use whatever materials they can find, including old cardboard, scraps of wood, or thrown-away furniture and household objects, along with inexpensive paint and tools.

In developing his definition of art brut, Dubuffet pointed out several criteria that must be met in order for an object to accurately be identified as this kind of artwork. First, such an object must be created by someone who was not educated at an art school. As a result, in general, works created by art brut artists do not take part in a dialog with the styles and critical ideas of familiar, mainstream art history.

Of course, almost all forms of artistic expression are rooted in the culture, history, or attitudes of a particular place, but as Dubuffet noted, often the best examples of art brut appear to be unique creations that have emerged from their own worlds, mostly unrelated to familiar cultures.

As a result, definitive examples of art brut and the artists who produce such works are often described as “visionary.” The paintings, drawings, sculptures, or other objects they produce express very personal visions — interpretations of various aspects of the known world or images of imaginary worlds (as in the fantasy universe of the Swiss art brut artist Adolf Wölfli or the land of monsters and armies of little girls in the large-format drawings of the American outsider artist Henry Darger).

Dubuffet emphasized that each individual work of genuine art brut and each art brut artist’s complete body of work is something unique unto itself. It is this fascinating, hard-to-classify nature of art brut works that captures the attention of admirers of this kind of art.

In Japan, the roots of what has become known today as “aaru buryutto”(in katakana, transliterating the original French term phonetically into Japanese) can be traced back to the period following the end of World War II.

A few years ago, I curated the exhibition Art Brut from Japan, Another Look, which opened at the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, in November 2018. The exhibition catalog Art Brut du Japon, un autre regard/Art Brut from Japan, Another Look, was published in 2018 in a bilingual, French-and-English edition, by the Collection de l’Art Brut and 5 Continents (ISBN 88-7439-846-1).

Photography Catherine Borgeaud Papi, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Photography Catherine Borgeaud Papi, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Photography Catherine Borgeaud Papi, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

This well-known museum, the first and the leading specialized institution of its kind in the world, opened to the public in 1976. Dubuffet’s personal collection of approximately 5000 objects became the core of this new museum’s collection. Today, the museum owns almost 70,000 paintings, drawings, sculptures, textiles works, and other objects.

Tadashi Hattori is an associate professor at Konan University in Kobe, where he teaches art theory and art history. He the author of the excellent book Outsider Art: Contemporary Art’s Forgotten Art(Kobunsha, 2003)

Looking back at the historical roots of art brut in Japan, in the catalog of the 2018 Swiss exhibition, Hattori wrote: “In Japan, interest in the art of the disabled first emerged around 1940. It was most typically reflected in [the] Advocacy Exhibition for Children with Intellectual Disabilities, an exhibition that was held at Osaka Asahi Kaikan in January 1939. What the organizers of this exhibition aimed for was to raise social awareness about the disabled and advance proposed governmental legislation to support them, something in which, at the time, Japan lagged far behind in comparison with other countries.”

In that same exhibition-catalog essay, Hattori also called attention to the single most significant aspect of the Japanese art brut phenomenon. That is that it has primarily been associated with social-welfare institutions for disabled people, in which art-making workshops may be found. As a result, and due to the efforts since the early 2000s of certain representatives of social-welfare institutions in Japan, almost always, whenever an article or news report in the Japanese media refers to “aaru buryutto,” it refers to art produced by disabled people. The emphasis is on the promotion and presentation of such artworks as a social-integration exercise for the people who produce them, not on the aesthetic aspects of their artistic creations.

It is true that, many decades ago, when he was doing his own research, Dubuffet discovered the works of numerous self-taught artists who had been diagnosed with mental illnesses and were associated with psychiatric institutions. However, in describing the essential characteristics of art brut, Dubuffet never insisted that a genuine art brut artist must be someone who has been diagnosed with a mental illness or any other kind of disability.

In the catalog of the 2018 exhibition at the museum in Switzerland, Hattori also noted that, in general, the promoters and presenters of so-called Japanese art brut exhibitions in Japan have been “amateurs in art therapy.”

As he pointed out, they are not specialists in art and “they are not curators or art critics.” Hattori wrote, “In Japan, in the name of art brut, those at support facilities for the disabled and government-run social-welfare programs have led a movement to promote art made by disabled persons without making a clear distinction between art therapy and art activity.”

Keeping all of this background history in mind, it is now possible to recall Japanese art brut’s more recent breakthrough events, which have helped bring the intriguing, highly original creations of self-taught Japanese artists to the attention of the international art world.

In the early 2000s, the American gallery director Phyllis Kind (who died in 2018) became the first art dealer in the United States to show works by contemporary Japanese art brut artists. At that time, at her gallery in New York and at the annual Outsider Art Fair, which takes place in New York in January, she began showing drawings and other works by such artists as Katsuhiro Terao, Mitsuo Yumoto, Tomoyuki Shinki, and Kazuhiro Yoshimune. All of these self-taught artists were associated with Atelier Incurve, a social-welfare organization in Osaka whose main facility is its art-making workshop for disabled participants.

Phyllis Kind’s interest in this art from Japan helped open the door to its presentation by other commercial galleries and by museums in the United States and Europe.

For more than 30 years, Cavin-Morris Gallery in New York has presented high-quality exhibitions of European art brut and American outsider art. Several years ago, this gallery’s founders, Shari Cavin and Randall Morris, established their own personal relationships with various sources of art brut works from Japan, including the Tokyo-based artist Monma (he uses only one name) and Galerie Miyawaki in Kyoto.

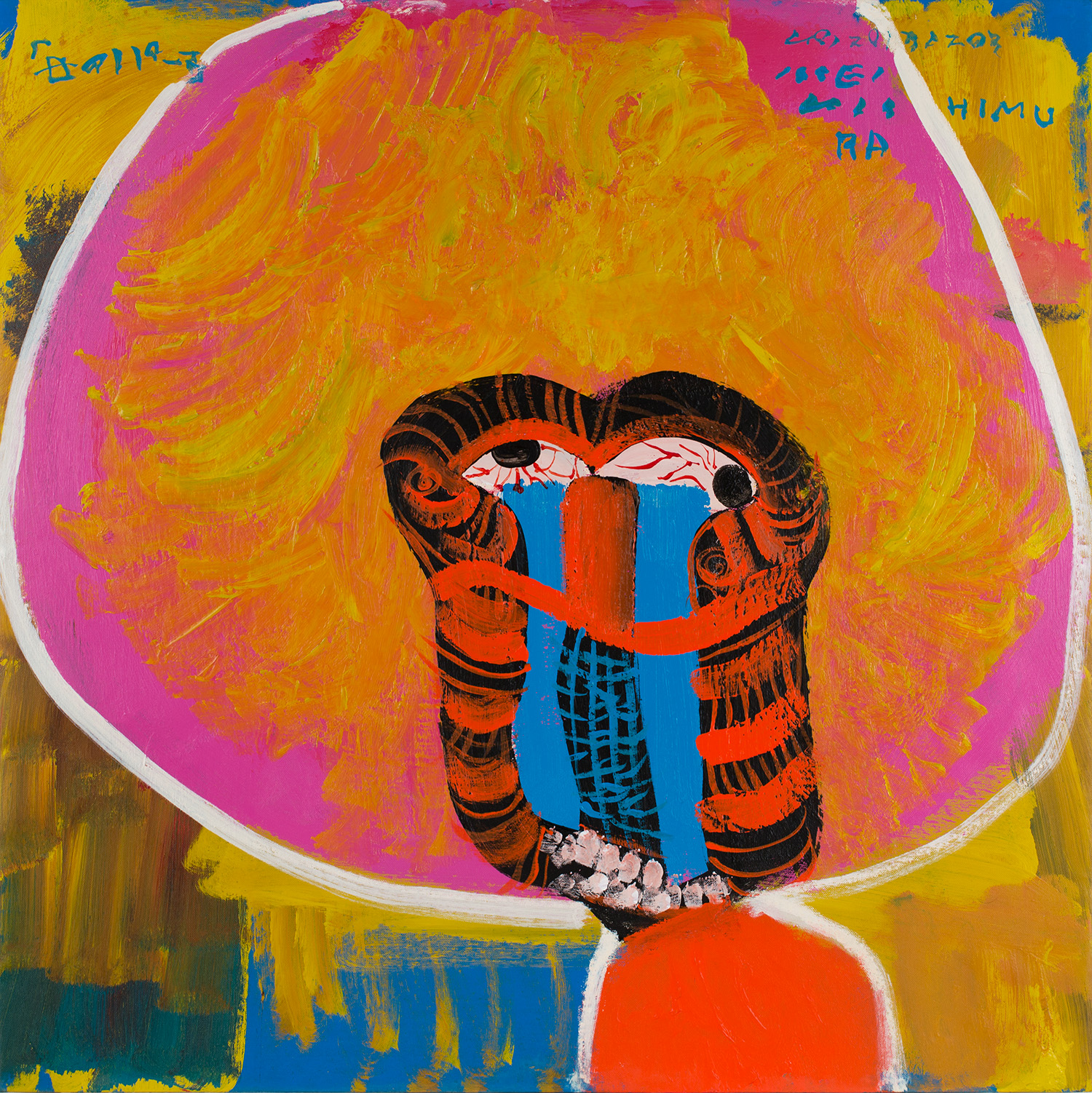

Yutaka Miyawaki, Galerie Miyawaki’s director, is one of the most active and well-informed presenters of genuine art brut in Japan. His gallery has presented exhibitions and published several notable books in this field. A few years ago, he introduced Cavin and Morris to the work of Issei Nishmura, a Nagoya-based maker of energetic paintings and drawings who is one of the Kyoto art dealer’s most original self-taught artists. Since that time, Cavin-Morris Gallery has presented Nishimura’s work in a solo exhibition and at the Outsider Art Fair.

Photography Edward M. Gómez

Photography Galerie Miyawaki, Kyoto, and Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York

Recently, Shari Cavin told me, “In the United States, we were the first to show the works of such Japanese art brut artists as Yuichi Saito, Yoshimitsu Tomizuka, Takashi Shuji, and Eiichi Shibata. As in Japan, art workshops for disabled people in the United States and Europe also have inventive programs. However, we have noticed that self-taught artists using clay or textiles have made especially strong, original works in Japanese workshops.”

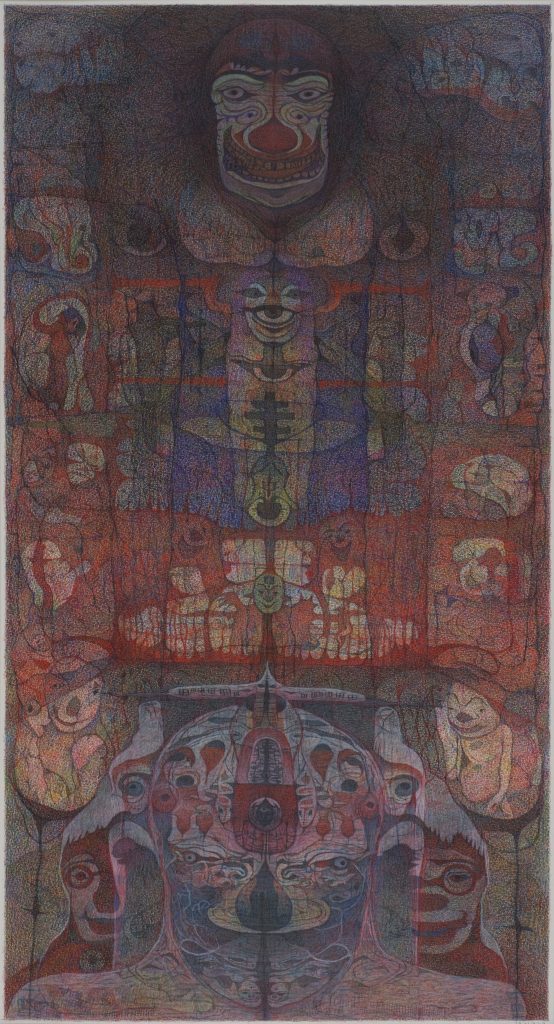

In the early 2000s, the introduction of art brut from Japan in the United States and Europe prompted a lot of excitement about and enthusiasm for such works as the bold, sophisticated drawings in pastel on paper of Takashi Shuji; the fired-clay sculptures of Shinichi Sawada, which depict otherworldly, imaginary creatures; and small, abstract drawings in ink on paper, gathered in tied-up bundles, made by Takanori Herai.

Photography Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York

Photography Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York

In 2008, the Collection de l’Art Brut presented Japan, an exhibition featuring the work of these three Japanese artists and nine others. In later years, other important exhibitions opened at the Halle Saint Pierre in Paris and at Le Lieu Unique in Nantes (in the north of France), among other venues in Europe.

In 2012, the exhibition Outsider Art From Japan opened at the Het Dolhuys National Museum of Psychiatry in Haarlem, the Netherlands. This same exhibition, now with the new title Souzou: Outsider Art from Japan, was later shown at the Wellcome Collection, a museum in London, where it offered a British audience an in-depth look at a diverse range of roughly 300 creations made by 46 artists.

Photography Jennifer Lauren Gallery, Manchester, England

Souzou: Outsider Art from Japan introduced foreign viewers to the three-dimensional textile works of the artist Yumiko Kawai, who for many years has been associated with Atelier Yamanami, in Shiga Prefecture, and also to the artist Marie Suzuki’s psychologically charged, colorful drawings referting to female sexuality.

After seeing the exhibition in London, I wrote an article about it for the Japan Times. In this review, I noted, “Representing a diverse range of art-making motivations, techniques, and themes, [this exhibition] features such unusual confections as Shota Katsube’s legions of miniature action figures fashioned from plastic-bag twist ties and Norimitsu Kokubo’s drawings of imaginary cityscapes, made with colored pencils and inks on enormous sheets of paper — one is several meters wide.”

The young art dealer Jennifer Gilbert, who founded Jennifer Lauren Gallery in Manchester, England, in 2017, presents exhibitions at different venues in London and other cities in the United Kingdom. In recent years, she has shown Japanese art brut artists’ works in England and at the Outsider Art Fair in New York. In a recent interview, she recalled, “The exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in 2013 attracted thousands of visitors. People are still talking about it today.”

How and where have works of Japanese art brut come to market both in Japan and overseas? How has the emergence of this kind of art affected the broader history of art brut? What are some of the most urgent critical debates concerning this kind of art, which have influenced how it has been appreciated, both within and outside Japan? We will examine these questions in part two of this article.

In part two, we will see what the Kyoto art dealer Miyawaki means when he says, provocatively, that Japanese viewers need to reconsider the history of art brut in Japan with “more understanding of this art.” Miyawaki argues that, in Japan, viewers need to “develop their eyes so that they may know how to look for and discover” this kind of art — and then properly identify it.