Chihei Hatakeyama is a musician who released a new album “Late Spring” from Gearbox Records. He started working on ambient music in the early 2000s. Looking back on the situation surrounding music in those days, new improvisational music scenes emerged simultaneously in cities around the world such as Tokyo, Vienna, Berlin, Chicago, New York, and London from the 1990s to the 2000s. Hatakeyama was timely exposed to these trends which were often described as “a new paradigm of improvisational music” or “sound improvisation,” in real time. And he became involved in the improvisational music scene himself in the late 2000s. In doing so, according to him, he came to incorporate improvisational techniques into the production process of ambient music.

In the second part of the interview, we will focus on the charm of the improvisational music scene in Tokyo in the early 2000s, which constituted one of his musical backgrounds, the utility of improvisational performance in music production, the relationship between live performances and recordings, and musicians he appreciates now.

“New attempts were coming out one after another.” The appeal of the improvisational music scene in the early 2000s

——In the second part, I would like to ask you mainly about the relationship between improvisational music and you. At the end of the first part, you said: “I used to go to improvisational live performances in the early 2000s.” It coincides with the time when Off Site in Yoyogi, one of the bases of the improvisational music scene in Tokyo was opened. Is there any event that left a strong impression on you?

Chihei Hatakeyama: I’ve been to the Off Site several times. Those were probably Sachiko M’s event and the live performances of Atsushiro Ito and Tetuzi Akiyama. The most shocking improvisational live was the Amplify Festival hosted by John Abbey from ERSTWHILE Records. It was held at the Star Pines Cafe in Kichijoji in 2002, and it was insanely interesting. Moreover, despite the fact that it’s an improvisational live, a lot of listeners came for some reason (laughs). But anyway, it was an event where domestic and foreign musicians gathered and performed in various combinations. I was particularly impressed by the duo of Thomas Lane and Marcus Schmicler. Thomas Lane was using an analog synth called EMS, which looked new to me.

——What kind of charm did you find in improvisational music at that time?

Hatakeyama: I like reading books, and I was struck by Atsushi Sasaki’s book “Tech Noise Materialism” (Seidosha) published in 2001. There is a chapter entitled “Free Improvisation in the 21st Century” that mentions musicians like Yoshihide Otomo, Sachiko M, and Derek Bailey. In retrospect, it’s unusual that Mika Vinio, Jeff Mills, and Satoshi Ashikawa appear in the same book (laugh). But at that time, It was quite common to talk about, say, Alva Noto (Carsten Nicolai) along with Taku Sugimoto. Anyway, using the book as a clue, I met music that I had never heard before, which was refreshing and interesting. Also, at that time, the technological development of equipments was visibly progressing, a lot of music that obviously did not exist in the previous era was appearing. I was attracted by improvisational music partly due to a lot of new attempts and equipments coming out one after another in this field.

—— At that time, haven’t you worked on so-called sound improvisation characterized by the stoic performances mainly consist of muted sounds and the frequent use of silence?

Hatakeyama: I had tried a few recordings before releasing my first album (“Minima Moralia”), but it wasn’t quite convincing. I liked listening to improvisational live performances, but when it comes to making my own work, I had to rely on my own taste and aesthetic . Otherwise I didn’t have any mean to measure the value of my work. Thinking about what kind of music would suit me, I thought the beat would impose a limitation on the sound. As such, I decided to start off with a quiet music with no beats, that has a glimmer of melody appearing occasionally, which came to fruition in an album called “Minima Moralia” released in 2006. So I wasn’t trying to do ambient or drone in the beginning.

——Did you get any clue for your own music production from the exposure to sound improvisation scene?

Hatakeyama: There may not be many people who think of it like this, but in terms of the influence from the improvisational scene at that time, the biggest thing would be “landscapes made with sound”. For example, the music of Toshimaru Nakamura and Tetuzi Akiyama has imaginative aspects that would make listeners imagine that the scenery of the sound changes and the “visibility” of the scenery is generated as time goes on. I was inspired by this kind of spatial width of sounds. Though “Minima Moralia” is often categorized as ambient music, I think it actually shares similarities with that kind of improvised music, such as the way the sounds are used, composed, and mixed.

Utilization of improvisation as a method in “Late Spring”

——You sometimes use improvisation as a method. For example, in this “Late Spring”, one of the concepts was “to find a good take from one-take improvisational recordings”.

Hatakeyama: That’s right. There are some songs that have been slightly modified, but basically all of them are recorded in one take. The concept for the seventh song, “Thunder Ringing in the Distance,” which is a recording of improvisational performance of an acoustic guitar, was to avoid overdubbing and to add no supplemental sound so as to keep as much of the sound as it was recorded. To put it the other way around, I had a specific concept for each song that would determine the direction of performance beforehand, and I recorded several performances made under that concept and adopted the best take.

——What inspired you to come up with the idea of “one-take improvisation” like a jazz solo album?

Hatakeyama: There are several triggers, but one of them was a gathering with Toshimaru Nakamura, Tetuzi Akiyama, and electronics player Ken Ikeda, which happened before the coronavirus pandemic. What we talked in that gathering was: “Rather than constructing sounds through overdubbing, a recording of one performance leads to a good piece of work.” Besides, I also work as a recording engineer. Now, DAW has become so convenient that we can easily replace just one part of song. So as part of my work, I was doing something like replacing only the ad-lib part in a jazz session with another take, which made me wonder if it is really okay to keep doing something like this (Laughs). With that kind of personal experience, I decided to record the entire performance as much as possible.

——It may be closer to the feeling that you prefer the unedited version of Miles Davis’ On The Corner. Is the jumpiness-like glitch noise in the 7th song “Spica” also one-take recording of improvisation?

Hatakeyama: That’s right. It’s also part of one-take performance with a modular synth. In that sense, I think that traces of my play are scattered in the sound. If you look for them while listening to it, even people who usually listen to jazz may be able to enjoy it.

——I think it would be interesting to listen to it along with Masabumi Kikuchi’s synth solo. For “Late Spring” you adopted a one-take recording of improvisation, but what do you think is the musical element unique to improvisation that cannot be obtained by constructing everything in a DAW in advance, for example?

Hatakeyama: It may be personal sense of time reflected in the sound after all. If you make everything with a DAW, the sound will be bound by the time signature. Of course, depending on the settings, you can create a tune in which its time changes, but it’s very difficult to do that by inputting all the required data. However, with improvisation, for example, the player’s sense of time that may slightly shifts on the spot is reflected even in a tune of a four-quarter time. With a sequencer of newest modular synth, the time of respective phrases match, but since it’s analog, it feels a bit out of sync compared to the sound made with a laptop DAW. But that’s not too bad.

“Even if the types of music seem totally different on the surface, you are able to trace their histories back to John Cage”

——By the way, I first learned about you not in the context of ambient music, but in the magazine “Improvised Music from Japan 2009”. You were interviewed in the article about the series of events “AFTERWARDS” co-hosted by you and sound artist Makoto Oshiro. Why did you start planning an event in collaboration with Oshiro?

Hatakeyama: To put it simply, our houses were close (laugh). I used to live in Fujisawa, but I moved to Nishiogikubo, Tokyo around 2007. At that time, Taro Nijikama invited me to the cherry blossoms viewing, and about 40 people gathered, including Oshiro. When I talked to him, it turned out that Oshiro had just moved to Tokyo as well and that his house was within walking distance from my place. That’s why I started going out with him for drinks and talking about planning an event together. After that, the first event was held in June 2008.

——According to the article, AFTERWARDS is derived from Natsume Soseki’s novel “And Then”, and one of the concepts was ‘thinking about “Afterwards” of music through events’.

Hatakeyama: Yeah, that’s right. I was hosting live shows where completely different types of musicians and artists were mixed. Until around 2010, such a different combinations were rather appreciated. So looking back now, the lineup seems quite chaotic (laugh). However, you will know that they actually share a common ground if you trace their roots. For example, if you trace back through the history of ambient music, you will first reach Brian Eno. And Eno was influenced by John Cage. In that sense, it can be said that sound art and live electronics have the same root. Even if the types of music seem totally different from one another on the surface, you may possibly be able to trace their histories back to John Cage. In other words, it also means you can’t see their common ground unless you trace the process back to that point.

——Do you still like to listen to Cage’s music?

Hatakeyama: What I often listen to lately is Arnold Schoenberg, under whom Cage was studying. While making audibly chaotic music using atonality and twelve-tone techniques, he sometimes added dark melodies or songs to his music. I really like such a balanced approach. Also, when I retraced Schoenberg’s music, I could tell that it was a difficult time for music to develop properly, partly because of two world wars and the unstable social situation. After the war, Cage began to become active as a composer, and the well-known “4’33” came out in 1952. It feels like there was a leap, or Cage skipped the history that was supposed to be there. It was too radical, wasn’t it? So, It makes me wonder what would happen if the history of music after Schoenberg had been built up appropriately.

——I see, the fact that Cage had such an impact makes us believe what you said about him: One will come upon Cage when he/she traces the history back.

Hatakeyama: Well, Derek Bailey began his quest for free improvisation in the mid-1960s, so it’s later than Cage in chronological order, but some part of Bailey’s music feels like a pre-Cage work. It may be partly because Bailey’s melody was influenced by Schoenberg’s disciple Anton Webern. But the biggest thing is that, in contrast to Cage who went too far ahead, Bailey traced the musical genealogy back to the point where Cage had not appeared yet, and reinterpreted the history leading up to Schoenberg.

“Reciprocal feedback between live performances and recordings”

——Compared to Schoenberg’s time, the factor of recordings has been added to Bailey’s activities as an important aspect of them. In 1970, Bailey launched his own label, Incas Records, together with Evan Parker and others. It is sometimes said that improvisation that put emphasis on one-time performance has poor compatibility with recordings that can be listened to repeatedly, but what is the relationship between live performances and recordings for you?

Hatakeyama: Personally speaking, live performances occupy an important part of my activities, although it’s hard to do them now due to the coronavirus pandemic. I often be able to go to the next step by going back and forth between live and recorded material. I try out the playing style I practiced during a live performance with a recorded work, or put what I thought during the recording at home into practice in a live performance. It’s a relationship where one factor provides another with feedback mutually. When I do a live performance by myself, it’s impossible to reproduce the sound that was precisely constructed with a DAW like a recorded material. So I try to make different music every time, using improvisational method as clues.

——Why did you start using improvisation as a method for recordings?

Hatakeyama: When I first started doing ambient music, I used to construct music elaborately with DAW. However, the result created out of this process was nothing more than what I have just expected, which often made me stuck. In the first place, I was not good at making something in accordance with plans (laughs). However, it was really big thing for me that I became able to edit music on a laptop PC. With it, you can play something on the spot and edit the material later as many times as you like. After the release of “Minima Moralia”, I started using improvisational techniques consciously to calm my mind and play without thinking in front of the equipment.

——You are also involved in label management and event planning, and sometimes plays the role of a producer in both live and recorded material. Are there any musicians who attract your attention now in relation to improvisational music?

Hatakeyama: There are a lot of musicians who capture my interest. Recently I was impressed by this musician called iwamaki who is making a tune by layering noise and drones with synthesizer in quite a geeky fashion. She sometimes appears in my events as well. Also, I think the following artists deserve attention: Leo Okagawa, a sound artist who often plays live at Suidobashi FTARRI and is very familiar with records, and Ayami Suzuki, an artist who uses her own voice for making/playing music and has released a duo work called “Undercurrent / Wanderlust” with Okagawa. Suzuki also sings with a guitar by herself, which is very good as well.

Chihei Hatakeyama

He released a solo album “Minima Moralia” from Chicago-based avant-garde music label Kranky under the name of Chihei Hatakeyama in 2006. Since then, he has released many works from independent labels in Japan and overseas, such as Rural Colors in the UK, Under The Spire, Room 40 in Australia, and Home Normal in Japan, and has also performed live tours overseas. He is well known abroad and was ranked in the top 10 of Spotify’s 2017 “Most Played Japanese Artists Overseas”. In April, the album “Late Spring” was released from Gearbox Records in the UK.

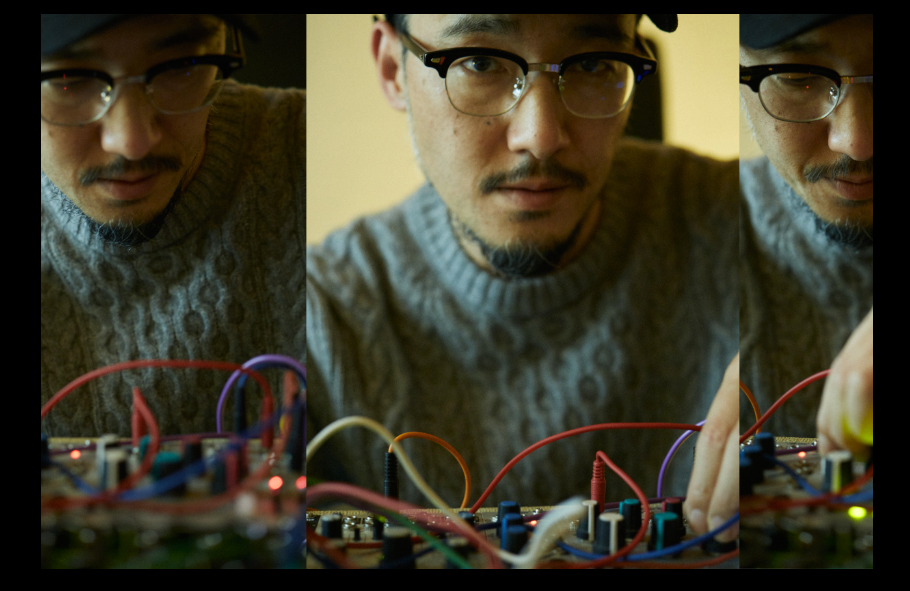

Photography Teppei Hoshida

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)

Translation Shinichiro Sato(TOKION)