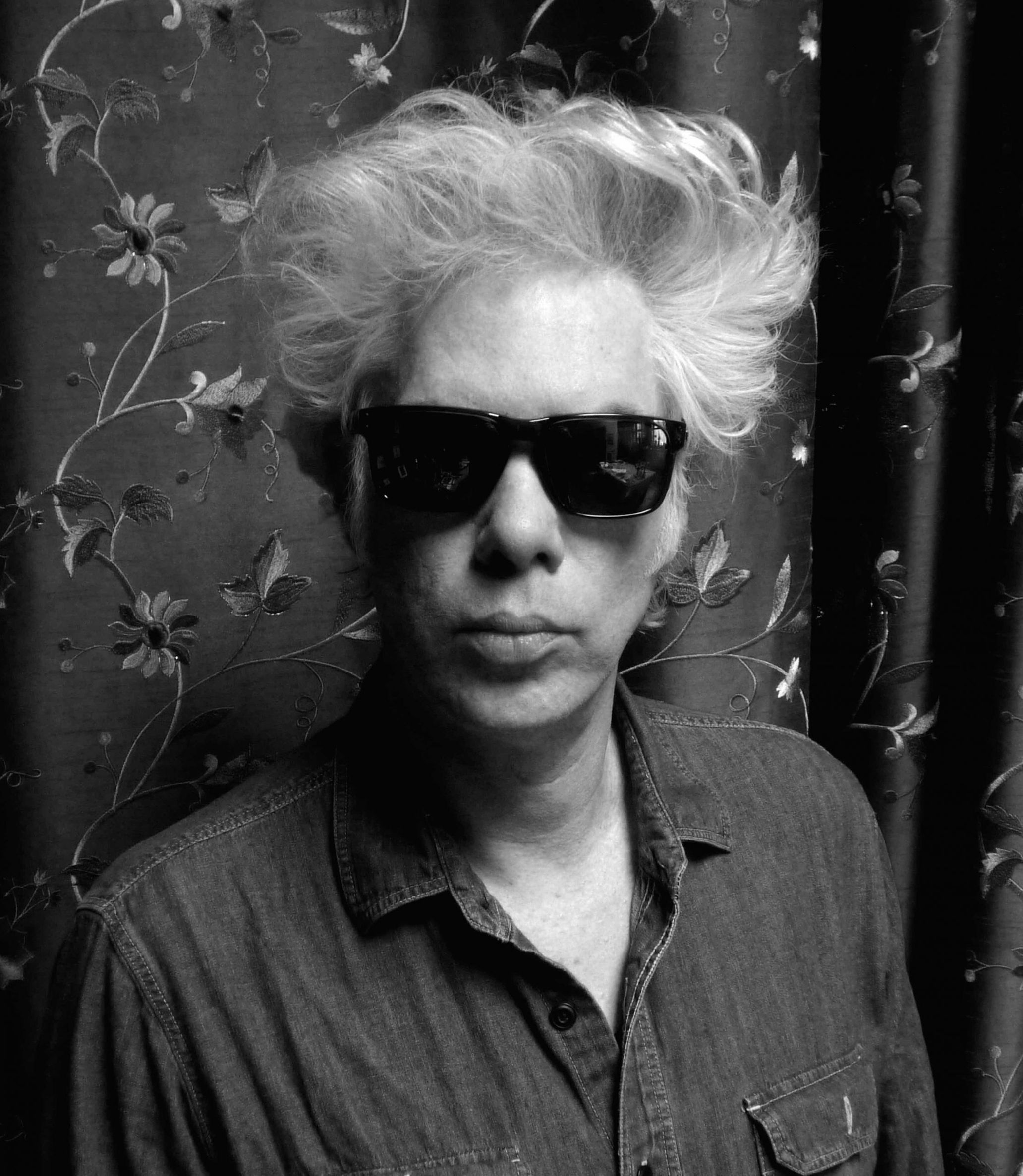

Jim Jarmusch’s first large-scale special screening was held in July. Twelve works shown in this event include his first feature-length movie “Permanent Vacation” (1980), “Stranger Than Paradise” (1984), “Down by Law” (1986), the movie Tom Waits was starred for the first time and “Mystery Train” (1989), in which Yuki Kudo and Masatoshi Nagase appeared and attracted a lot of attention. Jarmusch is known as a director who has a close relationship with many musicians and has a deep and extensive knowledge of music and those involved in music have played an important role in his movies. Let’s look back on Jarmusch’s footsteps and the movies and music he left behind.

©︎Sara Driver

The influence of Yasujiro Ozu’s works and the style of Japanese cinema were brilliantly digested in his works.

It wasn’t in the movie magazines that I first learned of Jim Jarmusch, but in the late-night TBS program “The Poppers MTV.” Hosted by Peter Barakan who is known as YMO’s lyricist, the show had been frequently playing video clips of British new-wave and so-called world music to capture the hearts of Western-music enthusiasts who weren’t satisfied with American chart music. Occasionally, Mr. Barakan also introduced his favorite Western films, one of which was the trailer for “Stranger Than Paradise.” Perhaps the lead actor John Lurie caught his eye because he was the leader of the punk jazz band The Lounge Lizards, which was causing a stir in the New-Wave scene in New York.

I found this movie really fresh not only due to its musical aspect, such as contemporary music-like BGM composed by Lurie and the eccentric blues number “I Put a Spell on You” by Screamin’Jay Hawkins, which is played many times in the movie as a theme song, but also due to monochrome cool images, incomprehensible jokes made in impeccable timings that would make audiences uncertain whether they should laugh at or not, and the seemingly unintentional screen layouts that were in fact perfectly calculated. Everything single aspect of it was fresh.

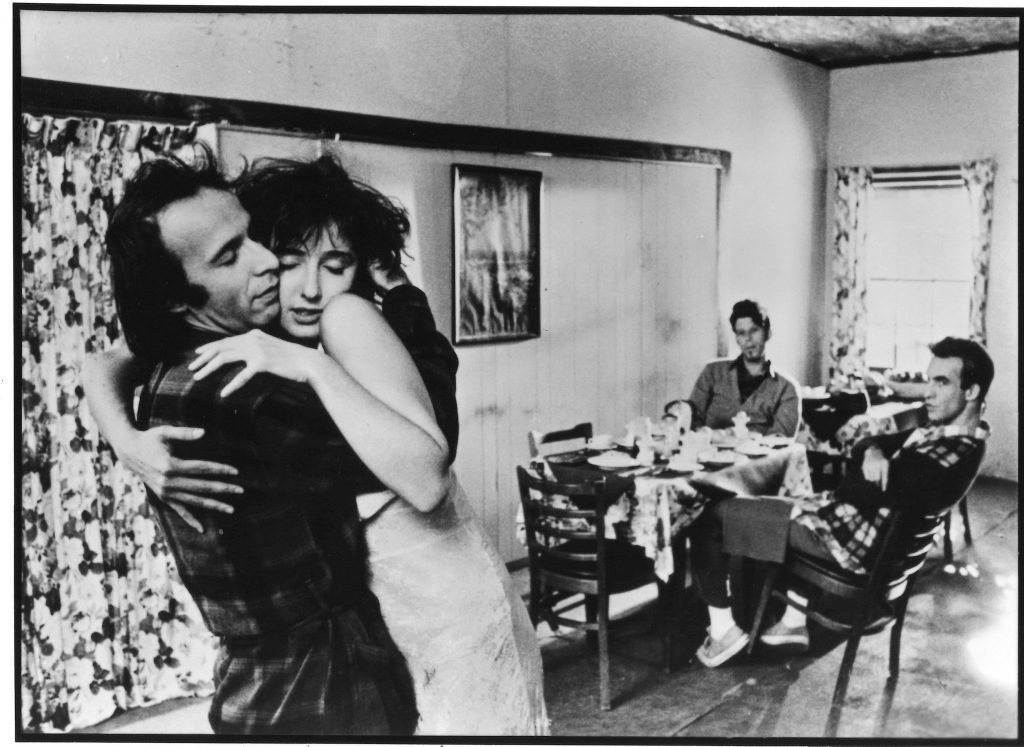

On the other hand, “Stranger Than Paradise” gave me a strange sense of familiarity. The characters in the movie are all quiet and have very few lines. I’ve heard that these silences confused many audiences in the United States, but for Japanese people, they were totally understandable. We knew those silences in the movie equal to “…” in the lines of the manga, and these are exactly where the true feelings of the characters are hidden.

We understood where these strange familiarities were coming from when we watched the scene where protagonists bet on horse racing and learned the names of race-horses: “Late Spring,” “Passing Fancy,” and “Tokyo story.” All of them are the titles of Yasujiro Ozu’s movies. Jarmusch is a worshiper of Japanese cinema. Of course, there had been directors who had expressed respect for Japanese movies, but no director had digested that style as successfully as him.

Perhaps partly because of that, “Stranger Than Paradise” released in Japan became a remarkable hit despite the fact that this was originally a movie for cinephiles. The independent theaters, which were called mini-theaters, were all packed with audiences. Movie poster of it were a staple of cultural boys and girls’ bedrooms until the advent of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. People called this movie by its abbreviated name “Stopara” and teased it in comparison with a comedy manga (I think it was Koji Aihara’s work). People also said “What’s so interesting about that? Everyone must be watching it forcibly”. In that sense, this was one and only indie movie.

© 1984 CINESTHESIA PRODUCTIONS INC. New York All Rights Reserved

Following the big hit of “Stopara”, the director’s first work “Permanent Vacation”, was also shown in Japan and became a hit. Filmed while he was in New York University, the movie gives a glimpse of Jarmusch’s cultural roots, which was not revealed in Stranger Than Paradise. The main character, the boy, is dressed in 1950s fashion, dancing to a hard bop as if he were cramping, and describes himself as an eternal traveler. Yes, Jarmusch was a man who admired Beatnik writers such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.

Beatnik was at the center of counterculture from the 1950s to the 1960s, praising dropouts from the regime and vagabond lives, but by the time Jarmusch moved to New York, it had already become a thing of the past. “Stopara” was a result of trial and error of Jarmusch who wanted to create a new expression method that inherits the spirit of Beatnik culture.

© 1980 JIM JARMUSCH

One and only filmmaker who draws literary series of short stories in movie format

Therefore, it was inevitable that Jarmusch teamed up with singer-songwriter Tom Waits in the laid-back jailbreak comedy “Down by Law” after “Stranger than Paradise.” In Japan, Tom Waits was underrated partly due to his catchy nickname “Drunk poet” or to an episode in which he had made his voice hoarse, longing for Louis Armstrong. However he originally was a Beatnik freak who had made a song “Jack and Neil” dedicated to Kerouac’s “On the Road”. Also he was a regular actor in Francis Ford Coppola’s work because both of them were fellow fan of Beatnik culture. (Coppola later produced the movie version of Kerouac’s On the Road).

© COPYRIGHT 1986 BLACK SNAKE INC

Coppola was a senior of Jarmusch as a filmmaker in that he had fulfilled his dream of continuing his career independently just as Beatnik poets in the movie industry that is pretty much all about the money. Coppola realized his dream by shooting blockbusters such as The Godfather and Apocalypse Now, but Jarmusch took a completely different approach.

The symbol of his approach is Roberto Benigni, an Italian actor who starred with Waits and Lurie in “Down by Law”. Although he attracted worldwide attention as a result of this work, he was already popular in his home country. Jarmusch sought to gain popularity outside the United States and secure his creative freedom by working with non-American stars. Through this perspective, we can understand why he starred Masatoshi Nagase and Yuki Kudoh in the first episode of the trilogy “Mystery Train” set in a motel in Memphis.

Starting with this work, Jarmusch has become one and only filmmaker who travels the world to draw “series of short stories” in a movie format. “Night on earth” (1991) depicts the interaction between taxi drivers and passengers in five cities around the world: Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome, and Helsinki. As the name suggests, “Coffee & Cigarettes” (2003) contains 11 short stories on the theme of coffee and tobacco.

© 1991 Locus Solus Inc.

© Smokescreen Inc.2003 All Rights Reserved

Perhaps, this unique attitude makes us think that Jarmusch has more friends in musical fields than in movie industry. Of course, the main reason is that he is a music lover himself, but probably because there are far more artists around the world who are earning money in many places in the world and doing their own activities freely.

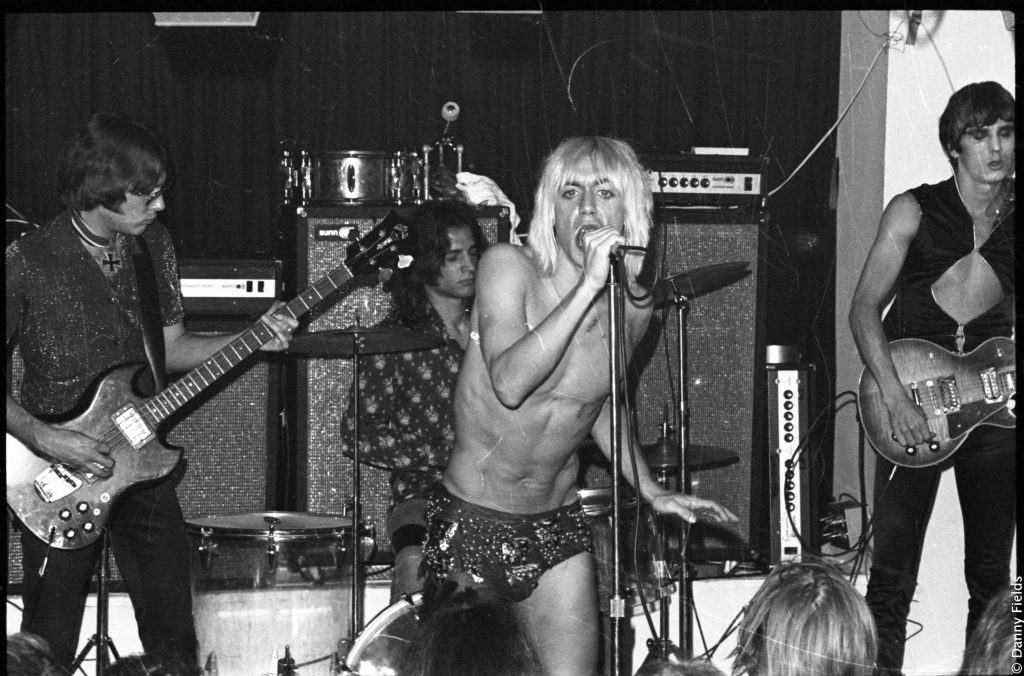

Musicians who have been driven by a friendship with Jarmusch to appear in his works include John Lurie and Tom Waits mentioned above, the late Joe Stramar who appeared in the final part of “Mystery Train”, leader of Utan Clan RZA who appeared in “Coffee & Cigarettes” and was in charge of the soundtrack for “Ghost Dog (1999)” and Neil Young and Iggy Pop who were featured respectively in two live documentary movies, Year of the Horse (1997) and Gimme Danger (2016).

© Mystery Train, INC. 1989

©️ 1999 PLYWOOD PRODUCTIONS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2016 Low Mind Films Inc

The Western drama “Dead Man” (1995), in which Young was in charge of sound track and Iggy appeared as an actor, was the turning point where Jarmusch was highly regarded in the context of American cinema. It starred Johnny Depp, who was already a star. However, if you watch the movie, you can see that Jarmusch was not getting intimidated at all, but rather taking an aggressive stance. The whole story was shot in black and white. Young’s music was a storm of noise guitar with no melody, and the main character William played by Depp is an accountant, not a gunman. Moreover, he was hit by a bullet in the early part of the movie and was destined to die soon.

With this movie as a trigger, Jarmusch came to be regarded as one of highly acclaimed director. And as a result, Hollywood stars such as Forest Whitaker (“Ghost Dog”), Bill Murray (“Broken Flowers”), Tom Hiddleston, Tilda Swinton, and Mia Wasikovska (“Only Lovers Left Alive”) , and Adam Driver (“Patterson “) aspired to work with him.

© 1995 Twelve Gauge Productions Inc.

©2013 Wrongway Inc., Recorded Picture Company Ltd., Pandora Film, Le Pacte & Faliro House Productions Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

©2016 Inkjet Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The latest work “Dead Don’t Die” depicts the reality of America itself

Jarmusch’s latest work, The Dead Don’t Die (2019), was an exciting work that dared to fake out the American film industry, who began to treat him as a big-name. It could belong to as a the genre of zombie panic movie. Therefore, it’s an surefire project in modern Hollywood, but he made it as an offbeat comedy.

Exaggerated acting is essential in this kind of movie, but he cast Bill Murray, Adam Driver, and Chloe Sevigny who tend to act in a deadpan tone, as main characters. What an ironic casting it is! All three are actors who have previously appeared in Jarmusch’s work, but this work also features Tilda Swinton, RZA, Steve Buscemi and Rosie Perez who have appeared in Jarmusch’s work. So it can also be described as a kind of reunion movie. Of course, his sworn allies Tom Waits and Iggy Pop also appear, and the character called Coffee Zombie portrayed by Iggy, who only speak “Coffee” is worthy of remark.

© 2019 Image Eleven Productions Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The zombies in “The Dead Don’t Die” have a strange habit of calling the name of what they used to love before they died. The pioneering work of this genre, “Zombies” directed by George A. Romero (1978) was set in a shopping mall, and zombies were depicted as a metaphor for people who were swayed by the consumer society. In that sense, “The Dead Don’t Die” can be said to be an orthodox zombie movie that draws on the essence of “Zombies.”

And the desolate sight of the city where zombies are roaming reminds us of locked-down cities under the influence of by the coronavirus pandemic. Jarmusch’s work, which was once totally fresh, now depicts the reality of America itself. Of course, that’s not because Jarmusch has shrunk to accommodate the taste of the audience. Rather, the United States has finally caught up with Jarmusch’s sensibility. It’s strangely emotional for me, a Japanese who has been watching over him since the beginning of his career, to witness that fact.