An incident in Shinjuku 2-Chome prompted a group of people to start organizing a party at a club and named it WAIFU. They displayed a policy that bans racial discrimination, transphobia, homophobia, and sexual harassment at the door. You could enter only if you agreed with the policy, and WAIFU turned into a safe space for people to enjoy the underground club culture like no other in Japan. On April 10, the organizers of WAIFU held a streaming event on SUPER DOMMUNE, which drew people’s interest as they discussed the history of trans culture and how it was connected to the club culture. The discussion also focused on issues about minorities including accessibility for people with disabilities at clubs.

Elin McCready transitioned to female in the U.S. and is in a same-sex marriage with Midori Morita. Midori is one of the organizers of WAIFU and SLICK, which is a series of outdoor rave parties. We interviewed Elin and Midori, the diehard club-goers, about their activities.

Discrimination Against Minorities Led to Starting WAIFU

――What was the incident that prompted you to start WAIFU?

Elin McCready: I went to a lesbian club in Shinjuku 2-Chome as a friend told me that Dora Diamant was going to be the guest DJ. (Dora was an iconic DJ of the queer scene in Paris.) Then, I was stopped at the entrance. I showed my passport, which stated my gender as female. Then, the bouncer got hold of another person, who insisted, “We don’t allow any trans women onto the premises. That’s our policy.” We were getting into trouble. Dora came by and said, “What’s the matter? Let her in.” She tried to persuade the owner, but it didn’t work out. Dora was about to start performing, but she went into the venue and retrieved her bag full of records. She said, “I am not playing. Good-bye,” and went home. The owner got really angry and screamed at us. The following morning, I told Midori about it and she was so enraged that she looked like a Super Saiyan.

Midori Morita: The government-issued ID proved that she was female. I started to question why there were no places or parties for trans people to go. We decided that we would organize events on our own rather than dealing with parties with shitty policies. I had been involved with organizing parties and I knew some people that I could reach out. This happened right before the Golden Week (a week in the beginning of May with many national holidays.) and many venues were already booked. However, Aoyama Hachi offered their place although there were some conditions. Once we held the event, we had more people than we anticipated. I realized that there was a need for gatherings like this. Aoyama Hachi said that we could hold the event on a regular basis. Hachi was busted in 2018 for letting customers dance until midnight, which was against the adult entertainment business law. I also wanted to take actions against the law.

――What are your thoughts on choosing a venue that was not located in 2-Chome?

Midori: First of all, I don’t have to go to 2-Chome. And, there are LGBTQ people, who go to 2-Chome, but are not necessarily big on the 2-Chome culture, where many bars play pop music by Diva-style singers. No matter which bar you go, you always hear the same music. I thought it would be cool to organize parties and build a club culture catering to these people in Shibuya area. Until Elin came out, I had no idea that 2-Chome could be uncomfortable for LGBTQ people. Most bars are for gay people and the percentage of lesbian bars is low. And, most entities are for cis people, and there are very few places for transgender and other sexual minorities to feel safe and enjoy their time. There is an existing power balance. We needed a place, which was not restricted by the existing conditions.

Elin: In 2-Chome, the majority is cisgender gay. Transgender, nonbinary, and asexual people —the minorities in the queer community— are ostracized. What happened to me was caused by discrimination against minorities. People go to clubs for two reasons: One is to enjoy music with high-quality sound; the other is to meet someone. In Berlin, most clubs specialize in music. Regardless of your sexual orientation, the club scene is really exciting. People’s gender identity or orientaiton is not necessarily relevant to how one is in the party context at all.

――Could you tell us why you decided to use the spelling “WAIFU” instead of “WIFE”?

Midori: When we decided to organize parties, the members were made up of different nationalities and background. We came up with WAIFU as a word that is known in both cultures and is an English word, yet we could use Romanized spelling. If you do an image search of #WAIFU, you end up with drawings of characters, which are moe-ish women with big breasts.

Elin: In animation and two-dimensional culture, there is a practice of calling their favorite character, “wife”, to imply that the character is your chattel. It’s the same as acting as if your wife were your property.

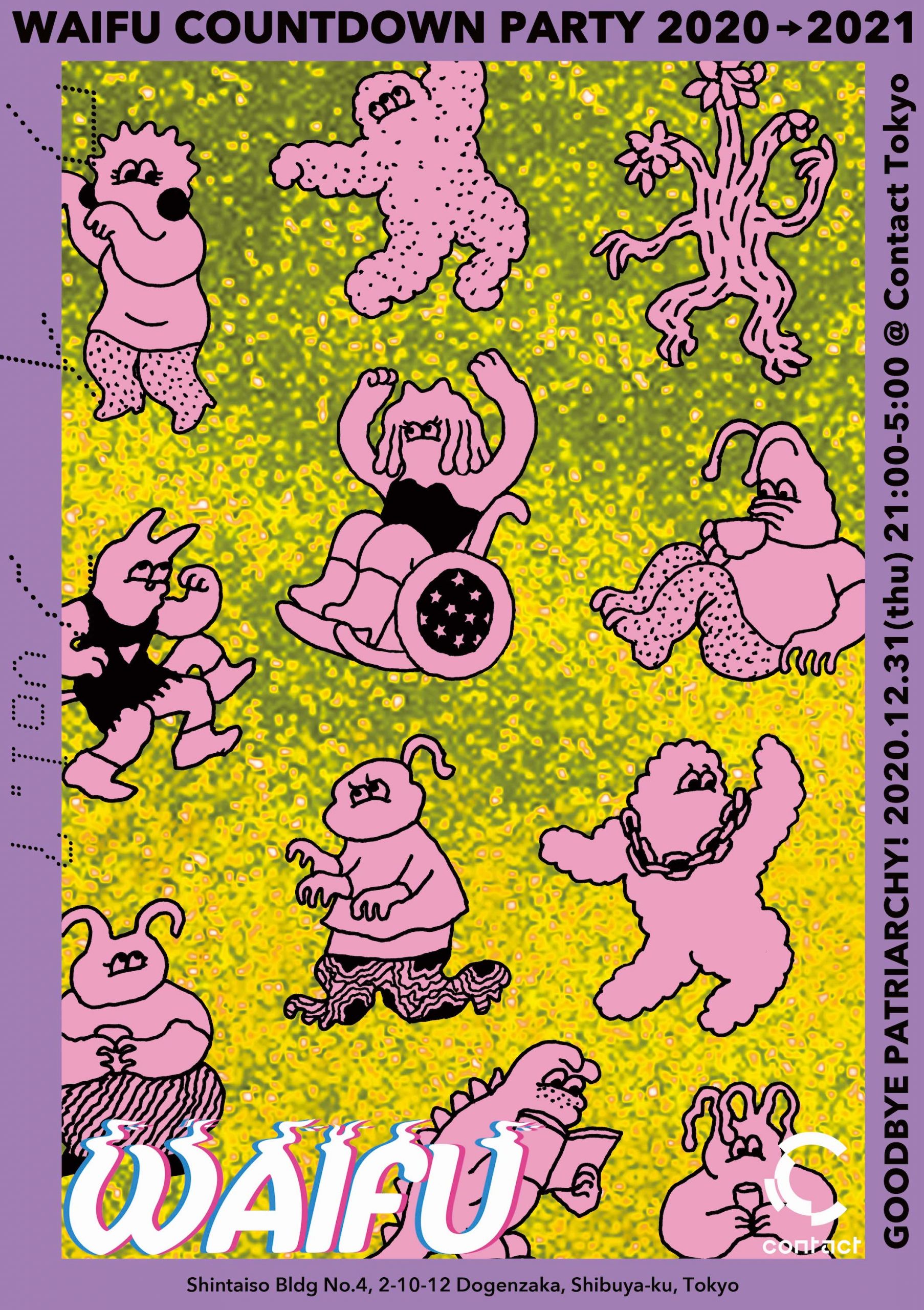

――What is the idea behind using pornographic and provocative illustrations? I am under the impression that it’s not in a positive context.

Midori: The word “queer” used to be a derogatory term, but there has been a movement to reclaim it by people daring to use it in a positive context. In light of that, one of the organizing members proposed the name WAIFU. It is not meant to be violent by objectifying Asian women and treating them as property. We thought it would be interesting if a search online for the word WAIFU would bring up many images of strong women one day as opposed to what we see now. At the same time, the two of us have been working for the recognition of same-sex marriage in Japanese law as “wife-wife”, so we decided to use WAIFU for a variety of meanings.

Elin: The old fliers and outreach videos used the spelling “WIFE.”

MIdori: Those were misspelled. We used a nude photo of a white woman for the first flier and it was controversial.

――Is it hard to navigate the complex world of sexual and gender minorities?

Midori: At one point, we were overwhelmed trying to deal with the complexity, but we would like to improve things gradually by listening to various opinions. We discuss and examine with the organizing members. As for WAIFU, the organizing members must understand feminism and LGBTQ. The logo and fliers are all designed by super-KIKI. Her title is feminist D.I.Y. Crafter. I would be happy if it make strong female images appear when people search for the word #WAIFU online in the future, and if WAIFU becomes a word that symbolizes feminism in underground culture.

――Do you feel that people don’t seem to understand what queer means?

Elin: We decided to organize a book club recently and I was thinking of picking up a book by Donna Haraway. However, the translated version of her book was extremely esoteric and was filled with difficult kanji and jargons in katakana. Maybe, no one is going to show up if I choose her book.

Midori: I think the fact that I am straight makes it worthwhile to be one of the organizing members of WAIFU. At times, I question, “What? What is that? What does that mean?” as a cisgender, straight person. I really want WAIFU and LGBTQ to be part of the larger society.

Elin: As for now, issues about gender and sexual minorities are

often only openly discussed in Japan and if you have no background, you can’t even express an opinion. Even within minorities, there is class and racial discrimination. But people else where have found ways to address these issues. For example, some parties in Berlin are very conscious of race and class.

A common goal in their lives.

――Has your relationship changed since your started WAIFU?

Elin: It’s hard to explain the change in a nutshell as my transition overlapped with the time we started to organize parties.

Midori: Until then, we were dealing with gender identity issue within the family. WAIFU was the turning point to start sharing the issues with the outside world and we became socially active.

――How did you deal with the rapid change in your life?

Midori: It was a drastic change. WAIFU became one of the pioneers in the Japanese club scene and queer community for stating the zero-tolerance policy at the door. The younger generation has also started to organize events recently stating the same policy.

Elin: After I came out as trans, I was featured in the media and people started to ask for my opinion. When I look back, I made some mistakes. I don’t think that was bad as my thinking shifts day by day.

Midori: Lately, I have been interviewed a lot about the new structure of our family. Elin and I used to be in a romantic relationship, but not anymore. She has a partner. I go through a phase of having a partner or not having one. Her partner was supposed to come to Japan and start living with us in January. However, it has not happened yet as the visa is not issued due to the pandemic.

Elin: I have not seen my partner for a year and it is really draining.

Midori: I am not sure what the alchemy was, but our relationship has changed drastically.

And, it didn’t get worse at all. The relationship we had when we met is completely different from the one we have now. However, I feel that we share the same goal in life. We want to hold on to our human rights and live happily. We want to do what we can to achieve that. I think that this is probably a common goal not only for us but for everyone.

――What was the challenge when you were organizing the parties?

Midori: We organized an all-night countdown New Year Eve event at Contact in Shibuya in December. We were going to have people in the venue, and even people who came to WAIFU parties started to complain, “How could you organize an event in a time like this?” Our stance of anti-authority is important and we have a sense of distrust and resistance against measures imposed by the government to contain Covid-19. Why do restaurants need to close at 8pm? Why do they have to stop serving alcohol?

――Couldn’t you agree with it?

Midori: Not completely. In addition to that, I really care about the younger generation, which was my motive to organize the party. If you are in your teens or twenties, “a year” is a precious period of time. If you tell them to stay at home because of the pandemic, it affects their mental health. The top cause of death among young people in Japan is suicide. Very few young people die of Covid-19 or illnesses. I wanted to support the young people and pushed my way through to execute the event. Before and after the event, people said all sorts of things and it was polarizing. It’s hard to figure out what is right immediately. You just have to make your own judgement.

Elin: We started to plan the event around October and November, and the Covid-19 infection rate was not increasing. So, we thought it would be fine. Then, there was a surge at the end of year, and, at one point, there was a discussion among the organizing members about canceling the event. But, the DJs had already offered to perform and we really didn’t have any money to cancel the event.

Midori: No, we didn’t have the money to cancel. At the same time, most performers really felt that it was more meaningful to hold an event under these circumstances regardless of getting paid or not. we also felt strongly about holding the event. If the club had asked us to cancel, we might have done so. As long as the club was willing to get people in the venue, I felt strongly about supporting the club culture. After that, all sorts of things happened and we took a break for a while from organizing parties and events. We did organize a memorial event on SUPER DOMMUNE on the anniversary of Dora’s death, who had passed away due to cancer.

Accessibility guaranteed, teaming up with the one and only underground “DOMMUNE”.

Midori: We invited Keita Tokunaga, a wheelchair user and a fashion industry journalist, and Tomoya Matsumura, a person with visual impairment, who launched a non-profit New Vision. They discussed about accessibility and clubs. Contact, the club in Shibuya, is one ofthe few places in Japan that can accommodate people with disabilities. The more underground the club is, the less accommodating the venue is for people with disabilities. When we were discussing about these issues on DOMMUNE, someone said, “Parco could be the best place in terms of accessibility. It has elevators and bathrooms for universal access that people with disabilities can use without any inconvenience. Why not organize parties at Parco?” Naohiro Ugawa, the head of DOMMUNE, was surprised to find out that Parco has advantages as such. Later, he touched on the issue at another event and declared that anyone with disability certificate can get free admission for DOMMUNE events. It is probably unlikely until the pandemic subsides, but it is possible to hold a party on Parco’s rooftop, and accessibility for all is guaranteed at this space. I hope that we can collaborate with DOMMUNE, which is an underground entity, to build a new platform together to convene events.

Elin: Queer people tend to isolate themselves, but they are kind because they feel other people’s pain, so it’s not like they can’t act out because of moral concerns.. I thought it was insupportable not to convene for the sake of abiding by the rules. We have to grasp the current situation and each person needs to act with responsibility.

――What kind of future do you envision?

Midori: I am so busy every day that I can’t think of anything concrete about the future, but it would be nice to organize events several times a year. It should be at a place with good conditions and open to all minority groups, featuring tons of brilliant underground performers. I hope to have actual events, not just streaming online.

Elin: I haven’t thought about the distant future, but I want to implement WAIFU in places other than Tokyo.

Midori: In Kansai area, there was an event called SLUT WALK OSAKA. We have been talking to the organizers of the event to collaborate down the road.

Elin: I am planning to live in Berlin for work for a year next year. It will be nice if I can develop relations with the queer festivals in Germany. Besides WAIFU, we started to organize an outdoor rave party called SLICK. WAIFU and SLICK have their unique characteristics and we want to keep them separate. WAIFU has its policies and we have the goal of creating a safe space using these policies and we create a safe place with restrictions. It’s queer and soft. On the other hand, SLICK is queer and hard. We have parties in Berlin in our mind. The performance we show at SLICK can’t be done at WAIFU. There is a risk that the it could remind people of past trauma. At SLICK, anything goes.

Midori: WAIFU is a gathering for people with awareness. As for SLICK, the point is to have people come and join the party regardless of their level of awareness. WAIFU might be too focused on becoming the safe place, but I think it’s important to have a place like that. We both need SLICK and WAIFU and will see what we can do to sustain them.

Elin McCready

She is a professor in the Department of English at Aoyama Gakuin University and a fashion model. She was born in Ohio and grew up in Austin, Texas. She holds a PhD in linguistics from the University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests are linguistics and philosophy, focusing mostly on semantics, pragmatics, and philosophy of language.

While studying at the University of Oregon, Elin became fascinated with the Japanese punk rock band BOREDOMS. In 1994, she had an opportunity to study at Waseda University. After graduation, she went back to Japan and met her wife, Midori. As club aficionadas, they hit it off and got married. After finishing graduate school, she worked as a researcher at the Osaka University, until she got her current position. She collaborates with Midori to organize WAIFU and SLICK events. She is also part of an art collective MOM that she formed with her current partner and Midori to present contemporary art work.

Midori Morita

Born in Nara, Midori is an artist and an event organizer. When the clubs started to pop up in the 90s, she decorated clubs as an artist using textiles, mainly in Kansai area. From 1994 to 1996, while teaching textiles at a university in Jordan as a member of JICA, she volunteered at a Palestinian refugee camp. She married Elin in 2000. They have three sons, Recently, she is focusing on nurturing creativity among young people. Her eldest son is a DJ and an artist in Tokyo. Since becoming a mother, she has been particularly interested in social issues and, in recent years, she has presented work in South Korea, which focuses on Japan-Korea relations and the state of post-war Japan.