flowers (AKAAKA Art Publishing), a photo book by photographer/director Yoshiyuki Okuyama, was published this year. The collection of photos he took over the years in his late grandmother’s home, which he now uses as a studio, is a dialogue with her via flowers. Until recently, Okuyama had presented many photographic works using people as subjects, so why did he publish a photo book depicting flowers and living space? We conducted an email interview to find out.

——How did you start taking photos for flowers?

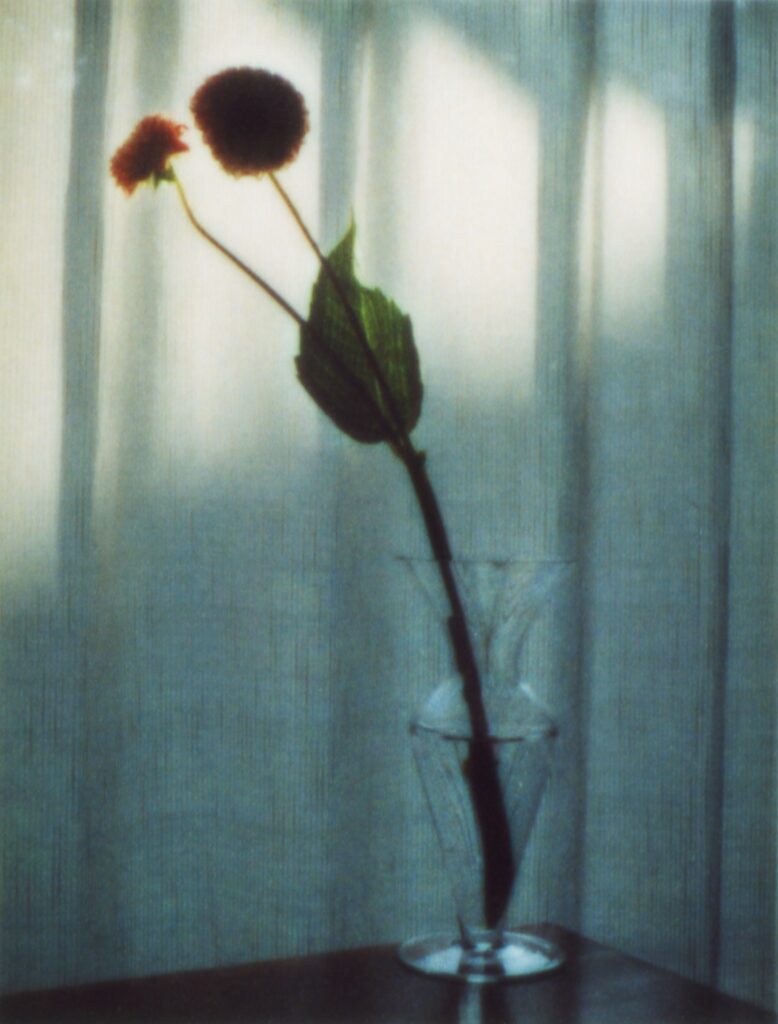

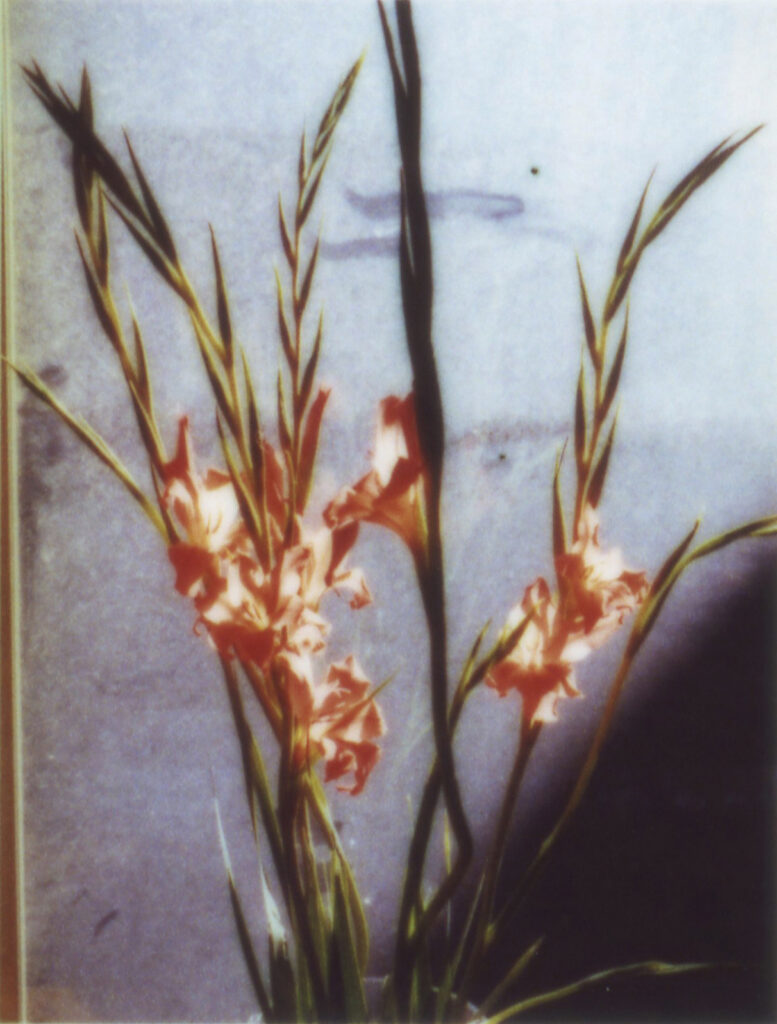

Yoshiyuki Okuyama (Okuyama): When I first met Megumi Shinozaki-san, who runs a flower shop called edenworks, she asked me to photograph unsold flowers before she had to throw them away. She wanted to preserve the flowers, which once bloomed beautifully but were decaying as living things do, by having me take memorial portraits. That resonated with me, so I began receiving one flower per week and photographing it in my studio.

The studio I use now is the house my grandmother used to live in while she was alive. I remembered how she loved to arrange and display flowers. Once I also started placing and photographing flowers on the windowsill, I eventually felt like I was having a dialogue with my late grandmother by facing those flowers.

When she was alive, we didn’t get the chance to talk to each other too much. You can say I’m still filled with regret whenever I press the shutter button today. The pretty sunset that illuminates her room feels oddly lonely, and I finally understand how she felt there. That’s why when I was photographing flowers, it was like having a dialogue with my grandmother. To take it a step further, I was photographing myself until that point, including my regret.

The initial impetus for me to create the book was photographing my grandmother’s empty house after she passed away. I wanted to know what perspective she viewed the house from and what she felt as she spent her days, so I placed large and medium format cameras on a tripod to photograph from an angle close to hers.

Then, I met Shinozaki-san. The structure of flowers is like a dialogue: it’s a mixture of my perspective of my grandmother through flowers and my grandmother’s perspective before and after her death, which I had already been photographing.

——Did you shoot the flowers that Shinozaki-san handed you just as they were?

Okuyama: Yes. Shinozaki-san had visited my studio a couple of times, so I entrusted her with selecting flowers. So, I just photographed the flowers she provided me.

——How long did it take for you to photograph flowers?

Okuyama: It took about three years, I think.

——Are you planning on shooting flowers in the future?

Okuyama: I currently don’t have plans on photographing them. Because [the medium of flowers] is a book, it’s important to hold exhibitions, get featured on different platforms to look at flowers from multiple angles, and allow the audience and me to transform it. With any piece, it’s not like it’s over once the book is complete; that’s the beginning.

With flowers, I had an installation with edenworks at PARCO MUSEUM TOKYO a year before it became a book. With that as the starting point, I could inch closer to the essence of [flowers] if I try exhibiting it in various ways over a long time.

A conversation with two viewpoints: “my grandmother’s perspective” and “my perspective”

——You used many types of cameras for the book, such as a 110 camera for flowers, medium and large format cameras to shoot spaces like the kitchen, study, and bedroom, 35mm, and polaroids. I was struck by how the main subject, flowers, were blurry, as you used 110 film for them while the photos of the rooms were crisp. How did you distinguish which cameras to use?

Okuyama: The theme of this photo book is “A dialogue with my late grandmother through the medium of flowers.” Generally speaking, it’s composed of two perspectives—my grandmother’s perspective and my perspective—going back and forth in a dialogue.

As for my grandmother’s perspective, I mainly propped 4×5, medium format, 35mm, and polaroid cameras on a tripod to photograph the interior. The key detail was the position of the camera on the tripod. I distanced myself from the camera and used a remote shutter release without touching the shutter button, so the camera could act like my grandmother when she was alive or after she passed away. By doing so, I eliminated the act of photographing as myself as much as possible. What did I have to do to make the camera be and see things as my grandmother rather than me taking photos with a camera? I expressed my grandmother’s unstable field of vision—she had a stooped posture—by making the tripod unbalanced and positioned at a low angle. By purposefully not making the [lens] focused, I recreated her weak vision. She was found lying on the floor when she passed away, so I photographed the view she must’ve seen. I dedicated myself to various techniques so the reader could also feel my grandmother’s perspective. I used comparably big equipment, so it could be separate from my physicality as much as possible. It made the camera exist as an independent thing.

On the contrary, to take photos of my grandmother via flowers from my perspective, I used equipment that was as small and light as possible and a camera that highly embodied [me]. To put it simply: a camera that’s like an eye and has no presence. Then, I coincidentally found a 110 camera my grandfather had used in the closet of [my grandmother’s] Japanese-style room. It’s way smaller than a 35mm camera. It’s so small it fits in the palm of your hand. Also, the fact that it belonged to the house was a deciding factor, as it felt natural and unforced.

More than the texture of the complete product, I chose the equipment according to the physicality [of the camera] when photographing things.

——You published your book with the title flowers, but did you always want to name it that?

Okuyama: This applies to any piece, but I rarely [take photos] with the goal of publishing a photo book. I only compile them into a book when I accumulate photos that make me think, “By publishing this series as a photo book, there’s a possibility the reader’s and my interpretation could change a lot later on.” Meaning, by cementing [the photos] as a book, people could draw a temporary conclusion from it. In contrast to their particular response at the time, when people look back on said book in the future, they’ll have new reflections on it. That in itself is the beginning of the piece. It’s the first step towards figuring out the essence of what the photos are conveying.

Personally, it feels like I’m making a time capsule when I make books. Once you make it, you can’t change the compiled photos, composition, design, or anything else. That’s why it makes you feel the passing of time and realize some things. Regardless of the genre, the crux is how much you can make the audience notice things in your work.

——Kaoru Kasai-san and Yuuki Adachi-san did the design for flowers. You previously worked with Kasai-san on As the Call, So the Echo. Why did you decide to work with him again?

Okuyama: Whenever I look at Kasai-san’s design, it always reminds me of an artisan with dirt on his hands. His bare feet are touching the ground, so to speak. [His work is] like a living thing, warm temperature, smelling the wind, listening to the sound of the stream. It’s as though this land we cherish is expanding in the background. I feel a warm kindness [from his work].

Previously, Masayoshi Nakajo-san wrote about Kasai-san, and there was a line that I related to deeply: “[He] unearths kindness, a quality that humans tend to forget, once more. Though what he was able to do with this theme comes from his character, the joy it brings is ours.”

For both photobooks, As the Call, So the Echo and flowers, I wanted to make a simple and honest book with that soft kindness at the core, which is why I approached Kasai-san.

——What did your grandmother mean to you?

Okuyama: For me, she was a symbol of kindness.

——Who do you want flowers to be seen by?

Okuyama: I wanted my grandmother to see it.

From how to take photos to what to take photos of

——This is slightly off-topic but has your relationship with taking photos changed at all because of the pandemic?

Okuyama: I don’t feel like my attitude towards photography as a whole has changed due to the pandemic.

However, there are things I can only shoot post-covid. One of the things I’m currently working on is to observe and photograph Tokyo post-covid.

——It’s been a decade since you won the Excellence Award for Girl in the 34th New Cosmos of Photography competition in 2011. What has and hasn’t changed regarding your way of thinking as a photographer?

Okuyama: A significant change is how my interest has shifted from the act of photographing to themes, subjects, and coming face to face with external elements. When I started out ten years ago, I would pursue technical photography skills and go through trial and error every day. But I began spending more time thinking about what I want to take photos of instead of how I want to take them. Of course, before I can think about what I want to photograph, it’s a given that I have to think about how to do it. But the [amount of] time for that has decreased. I barely get started by [considering] how I want to photograph.

What probably hasn’t changed is my sincere attitude towards creating things.

——Is there anything you have in the back of your mind when you shoot?

Okuyama: My state of mind changes depending on the time and place, so it’s generally hard to say. But I can say I always work on something with honesty.

——Lastly, you’re working more and more as a director, including directing for commercials. Is there anything different for you between creating moving images and still images?

Okuyama: In my case, when I make both films and photos, I’m making a production, so there isn’t a big difference in how I view them. But teamwork is certainly more imperative when filming because there are more people involved. I can’t do anything alone. Communication between the staff, cast, and everyone involved directly informs the finished product. Of course, communication is important in photography too. But ultimately, it feels like I’m doing that all on my own. On the other hand, with filming, everyone’s part of a team from start to finish. From preparing, filming, to the finishing touches, every word I say to everyone becomes part of a production, so I work with a sense of nervousness.

Yoshiyuki Okuyama

Director and photographer. Born in 1991 in Tokyo. In 2011, Okuyama received the Excellence Award for his photo book titled Girl by 34th New Cosmos of Photography. Then, he received the Photography Award for the 47th Kodansha Publishing Culture Awards in 2016 for BACON ICE CREAM. Okuyama’s noted photo books include flowers, As the Call, So the Echo, The Good Side, The Town You Live In, POCARI SWEAT, Los Angeles / San Francisco, and so on. Okuyama’s celebrated exhibitions include BACON ICE CREAM (PARCO MUSEUM TOKYO, 2016), The Town You Live In (Omotesando Hills Space O, 2017), As the Call, So the Echo (Gallery916, 2017), White Light (CANON GALLERY S, 2019), and so forth. Furthermore, he creates TV commercials and music videos as a director. A Taiwanese edition of BACON ICE CREAM was published this summer by Taiwanese publisher Uni Books.

https://y-okuyama.com

Twitter:@okuyama_333

Instagram:@yoshiyukiokuyama

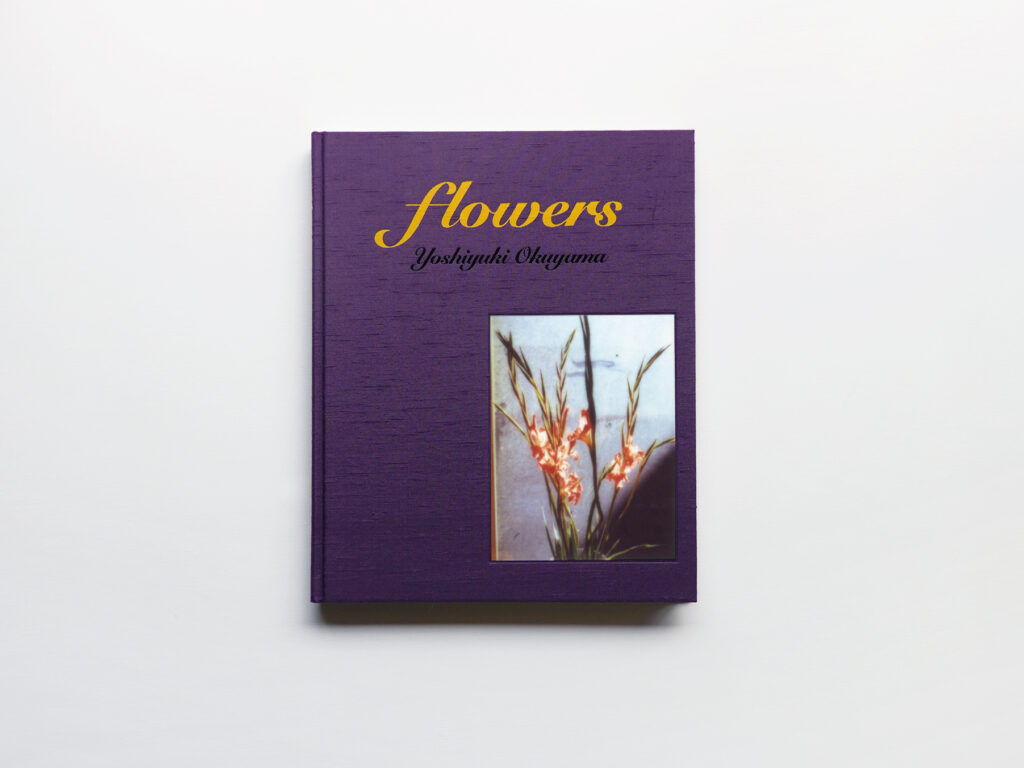

■flowers

AKAAKA Art Publishing

¥ 5,000+tax

Book Design:Kaoru Kasai,Yuuki Adachi

Size: H261mm × W216mm

Page:152 pages

Binding:Cloth Hardcover

http://www.akaaka.com/publishing/flowers.html

Translation Lena Grace Suda