The first part was about Sibitt’s discovery of hip hop and theater. This time, he spoke about his work regarding writing, which is at the center of his expression, and his new project, 8 ∞, which includes participants such as Rully Shabara and Gozo Yoshimasu.

The initial urge to write an idea

—In Oto de Miru Dansu, you’re credited as a narrator. Is what you did with that role similar to what you do today?

Sibitt: Yes. It’ll be interesting if I could pass down things people don’t know about, or if someone else could pass it down after I die like, “Here’s a story of something that happened.” I think of myself as an “ear person,” as I think everything in this world is music. I believe in sounds more than the visible world. I thought about how I would enjoy dancing if I lost my eyesight one day. I wanted to create a story through a person’s dance and make the audience listen to things they usually wouldn’t listen to and feel something. I told a story that I had envisioned in fine detail from watching the dancer, Neji-san, dance.

—How do you rank the act of writing, speaking, singing, or rapping?

Sibitt: The act of writing comes first. It’s an impulse. I can’t help but write to an unhealthy degree.

—So, writing comes first?

Sibitt: More so than writing, it seems like I get a flash of inspiration like, “Oh!” I’m driven by this sense of duty to write an idea when I get one. When I write, it feels like I enter a forest of words and go on a journey of seeing where they take me next. I think I say the words aloud, whether it’s a meter of a poem or just my voice. As of late, I’ve begun digging even deeper; I wonder, “Why is it shaped like that?” [when I see] just one letter. I got an offer last year from a museum of kanji (Japanese characters) in Kyoto to show an exhibition about where kanji or words originate. They already have a meaning to them, but the museum wanted me to have a two-month exhibition where I trace back the origins. However, because the state of emergency was issued, it became an unfulfilled exhibition. I didn’t even do it for a week. But it reaffirmed the joy of words for me. It was an eye-opener, as it made me question why I hadn’t thought about something so interesting before.

—I see. It turned into a process of rediscovering sounds.

Sibitt: Regarding the act of writing: when the exhibition started, I tried looking at other people’s and my writings again, as though I were using a magnifying glass. For instance, the left and right sides of the kanji for 行 (read as gyo or ko, meaning line/verse/row) look similar, but [one side is] a bit slanted. Perhaps this is because long ago, people didn’t have matching straw sandals. Perhaps on their “way to” (行き, read as iki) somewhere, they would wear a sandal on their right foot, wear one on their left foot on their way back, and adjust the balance. I imagine 行 represents the shape of straw sandals. A big reason why I trace back the roots of words is because of a theme I have, which is “The future is nostalgic.” We don’t know what the future holds, so I know it’s weird to use the word nostalgic. The “Ah, I’ve seen this before” feeling, as if I’m going back in time, feels fun again.

Shinganginga Shokei, the result of having an inquisitive spirit towards words

—On the flip side, there are some cases where the past feels new. Is your interest in language related to the book version of Shinganginga?

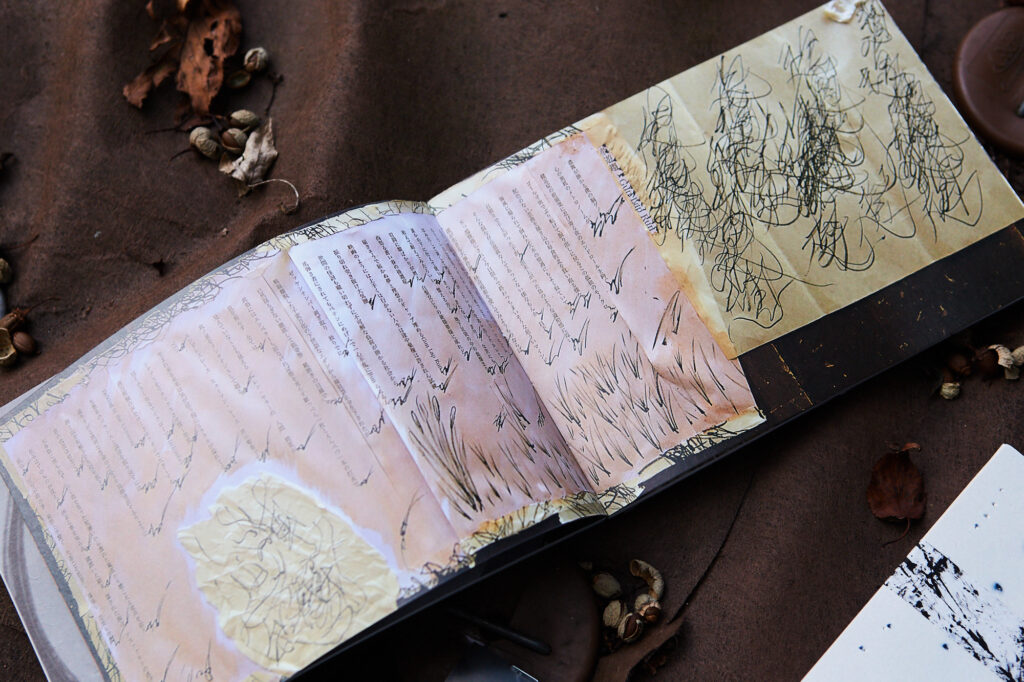

Sibitt: Yes. Because I wanted people to see my exhibition, when I was making Shinganginga, I honed in on succumbing to the act of looking at words through a magnifying glass. I didn’t make the works overtime, though. I made them in about two weeks, nonstop. I wrote them, hit them, erased them, got on top of them to step on them; I made them using various frictions.

https://sibitt.exblog.jp/28546796/

Photography Kazuo Yoshida

—I was surprised when I picked up the physical book, as it has such a demanding presence. I felt the power of your photographed works and the joy of the words themselves.

Sibitt: It would make me happy if people want to read the actual thing, or if people who work with words or art could use this opportunity to take a good look at what they do. Right now, we can’t touch, and we need to distance ourselves from one another; we can’t even shake hands as much. We’re not conscious of what we touch each day. On the other hand, in the world, there are people like Satoshi Fukushima-san (editor’s note: a researcher of accessibility issues and a professor at the University of Tokyo) who are deafblind. We mustn’t forget that some people understand words for the first time when people touch their fingertips using finger braille (editor’s note: a method of communication for deafblind people using six fingers—the index finger, middle finger, and ring finger on both hands—as a braille typewriter). Satoshi Fukushima-san talks about the world of touching with his fingertips. It’s vital to think about what we touch today.

8 ∞, a project with international artists, and meeting Gozo Yoshimasu.

—That perspective ties in with a current project you’re working on, 8 ∞.

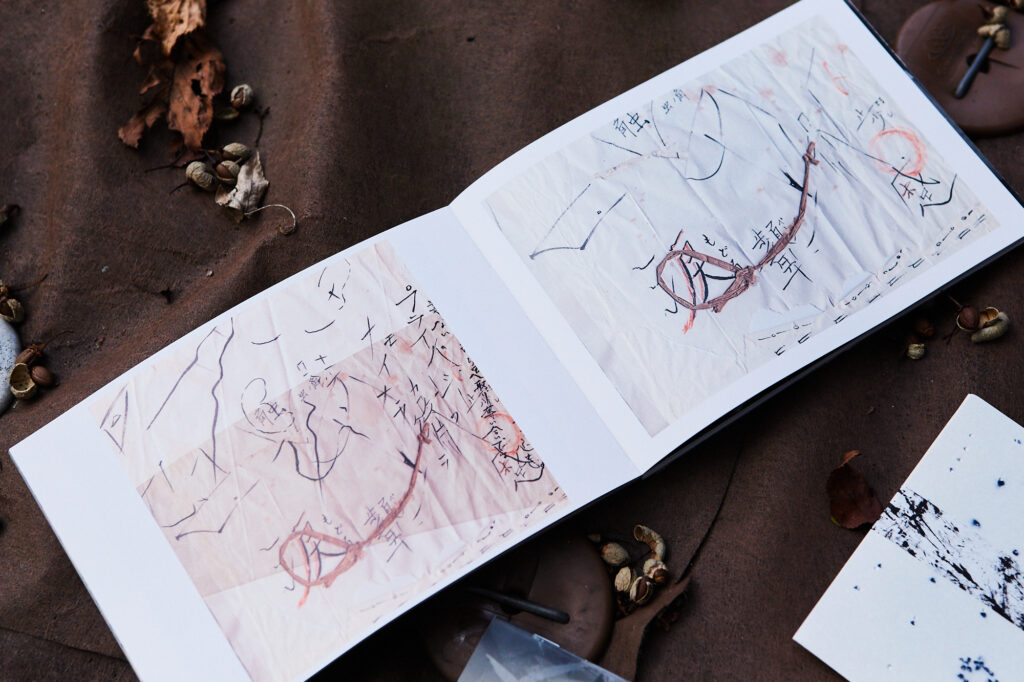

Sibitt: 8 ∞ is a project where instead of just creating my work, I look at completely different people’s work with a magnifying glass and make things that make me think, “Doesn’t this mean x y z?” with this person with a Ph.D. degree from Hiroshima University and other people. When I worked in a hip hop environment, I didn’t care about other people and didn’t seriously read other people’s lyrics or written works. I read your work and so on and analyzed it by looking through a magnifying glass, like “I wonder what this person was doing.” It was fun to deepen my understanding, and I started approaching people. For example, I had Gozo Yoshimasu (editor’s note: a poet born in 1939 who represents contemporary Japanese poetry) read “Irezumi,” a poem he wrote in the 70s, in his voice. He gave me a letter, and that is a work of art in itself. I felt like the gaps in each line had some meaning, like a signal. I felt like it was an artwork, not a letter. My current mission is to see how seriously I can deal with other people’s poems because I met someone who pours their energy into understanding other people’s minds by interpreting their poems, going to the place that inspired said poems, and writing after breathing the air they breathed.

—How did you meet Yoshimasu-san?

Sibitt: As a university student, I only read a few of Yoshimasu-san’s works. Like I said before, I wasn’t interested in other people (laughs). I started 8 ∞ because I wanted to, and I don’t know when the project will end. I reached out to Gary Snyder for it. He replied to me saying, “I can’t participate this time because I’m finishing a big collection of poems.” His reply was a poetic one, too. He told me he was looking forward [to my project]. I approached different people like Saul Williams and Kae Tempest (formerly known as Kate Tempest), but it was spontaneous. So, I didn’t know about the current scene or anything. Little by little, I reached out to people who made me wonder what poems they were writing and what they’ve got to say, as well as the surrounding people. And I thought Yoshimasu-san was an obvious choice.

—You approached people you didn’t personally know.

Sibitt: Yes. I contacted a bookstore in Hokkaido called Shoshi Yoshinari. I wrote a long letter to them, and they got me in touch with him. I was just actually on a phone call with Yoshimasu-san this morning.

—Yoshimasu-san used to work with jazz musicians. Also, because of the jazz poetry movement in America, he became a spiritual pillar of jazz. People like Saul Williams, Kae Tempest, and Mike Ladd all have connections with hip hop. I feel like your work as an artist today draws from these movements.

Sibitt: I don’t think that way at all, but I have this extreme [belief] that you can understand the world if you listen to the words of a poet, that it’s everything. I think it’s my misunderstanding, in a good way. Different information and words are everywhere, but poets sift through them all and leave one speck of words. I want to believe in this big misunderstanding that if we listen to the words and voices of poets, then it’s enough for that to be the entire world.

—We can’t be out in the real world as much because of the pandemic. As such, some people are more aware and sensitive about words than before. As such, I bet people are showing interest in 8 ∞.

Sibitt: A vocal artist from Indonesia called Rully Shabara sent me a handwritten poem, an audio recording, and a typed-out piece. It was all in a language he created. Nobody can speak it or understand it. He even invented the letters. He’s in a different ballpark; he doesn’t make you understand, and yet, when you listen to his voice, you could picture things like a dolphin or water. When I saw that, it made me think back to how people first wrote words to communicate something, like how a child writes backward or writes made-up words. We should know that people think about many different things even though they feel frustrated when they can’t or don’t know how to communicate and don’t understand another person even though they’re trying. When you read Satoshi Fukushima-san’s book, you’ll learn that silence is scary, like silence is hell. There was a time when he begged people to talk to him about anything, as he felt like he was alone and floating in space due to not being able to see and hear others and himself and come into contact with what others were saying. We must understand that some people don’t want to be spoken to while some think the exact opposite. I wonder what words we should say to them in such situations.

—You express the idea of not being understood and not understanding in Shinganginga.

Sibitt: Shinganginga derived from 8 ∞. In about the second song, I say, “Breathing is living.” When we talk to vegetables or trees, we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, so it’s as though we grow that way. I feel like what poets, or those who speak to others in a particular field, do is equivalent to them saying, “By listening to voiceless voices, I think about what I’m encountering and what I should be listening to. As long I could hear that, it’s enough.” I want people to know that such people exist in the world. Though they may not appear at the forefront, those who work to express people, language, and talking to others exist all over the world, and I look forward to that. As I meet more people, it reminds me to spend time with and listen to people’s words.

Field recordings; everything is music

—After you made Shinganginga, you made an instrumental track called “Chikyu Naut Ouou,” (CHIKYU NAUT -翁嫗 OUOU- 語部:志人/sibitt). It’s an interesting ambient song based on field recordings, and it doesn’t have a beat.

Sibitt: When I made that, I was asked to do a long-distance poetry writing workshop with people who worked in a social welfare facility. Because there was a delay due to it being long distance, and the event hosts wanted to forcibly make something out of it when I didn’t think we had to rush. So tension arose, and we couldn’t create anything. However, during the few weeks I spent with them, I made “Chikyu Naut.” They inspired me to make it.

—Was it your first time using a field recording?

Sibitt: I have a recorder around me every day and have been using it for about ten years out of habit. But I haven’t used them in my work until now.

—So, it’s not like you listen to the field recordings and then write something down?

Sibitt: I have a studio in a warehouse made out of clay, and I always hear the sounds of nature in the background. When I play the synths or listen to an audio recording, how it sounds changes depending on the rain, a quiet night, or when many frogs cry. On top of making something everyone can listen to, I hope to demonstrate with ease that everything is music instead of coming up with words, as I believe the sounds in people’s homes add to the music. I want to go somewhere and think about making field recordings. I still don’t know what I want to do, but I want to travel more.

Sibitt

Sibitt was born in Japan in 1982. He is a poet, author, songwriter, and storyteller. Through examining his means of Japanese expression, he has become an artisan of words who shows new possibilities hidden in language. Aside from music, Sibitt works as an artist in domestic and international performing arts and classical theater. Starting in 2020, he began hosting 8∞, a project of endless stories with international artists. Currently, seven poets/ “voice performers” are involved: Sibitt, Khyro, Rully Shabara, Nanorunamonai, Bleubird , Bianca Casady, and Gozo Yoshimasu. In 2021, Sibitt released his self-produced album, Shinganginga alongside Shikakushi・Shokkakushi Shinganginga Shokei.

sibitts official blog Wheres sibitt? : sibitt.exblog.jp/

TempleATS: templeats.net/

8 ∞:88project.info/

Translation Lena Grace Suda