Paris-based composer/artist Ryoji Ikeda has continued to revolutionize the electronic music and sound/media art landscape since the mid-90s through his radical and innovative pieces, performances, and installations. On October 23rd, Ikeda had his first solo live show in Tokyo in roughly five years. He also screened “superposition,” which he has shown globally since 2012 but not in Tokyo. It was a rare chance for people to experience Ikeda’s recent and current art. In this article, ICC chief curator Minoru Hatanaka, who’s been loyally up-to-date with Ikeda’s career, including his time in Dumb Type, reflects on the audiovisual performance and the true worth and possibilities of the esteemed Japanese genius.

The debut of “superposition” in Tokyo

After five years since 2016, Ryoji Ikeda held a live show titled “Ryoji Ikeda [live set]” and screened the film version of the performance piece “superposition,”titled “Ryoji Ikeda superposition special screening,” at WWW and WWW X in Shibuya.

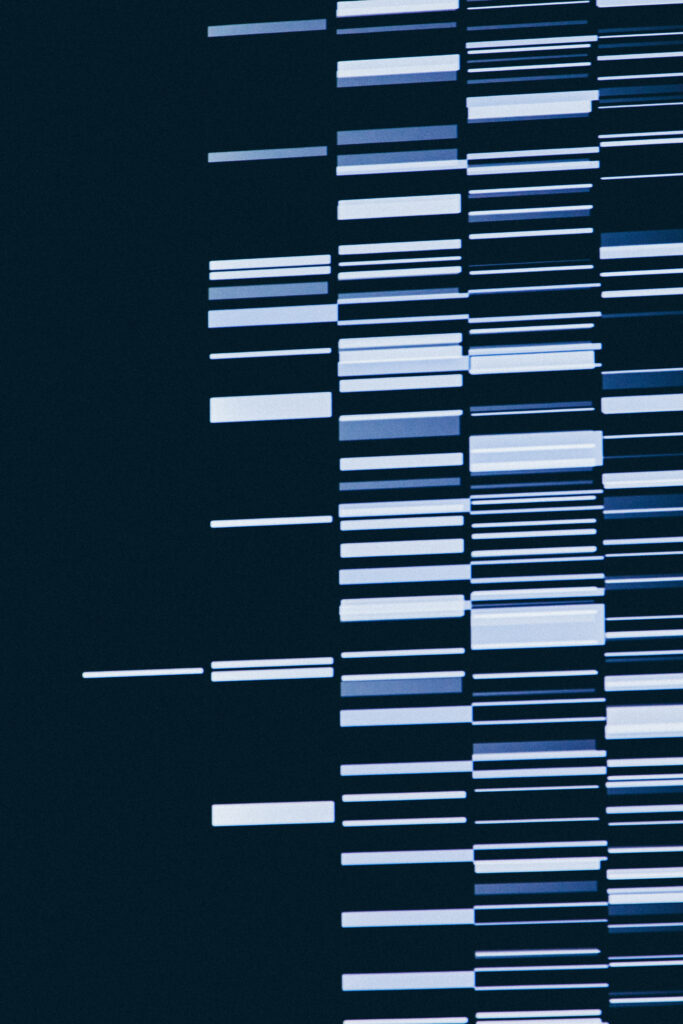

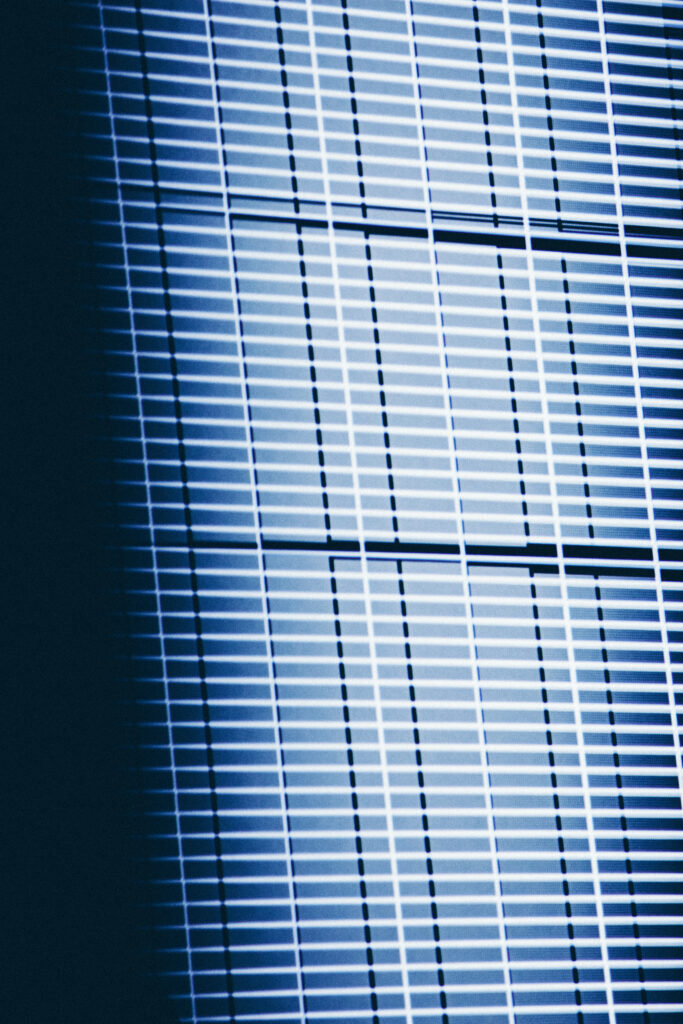

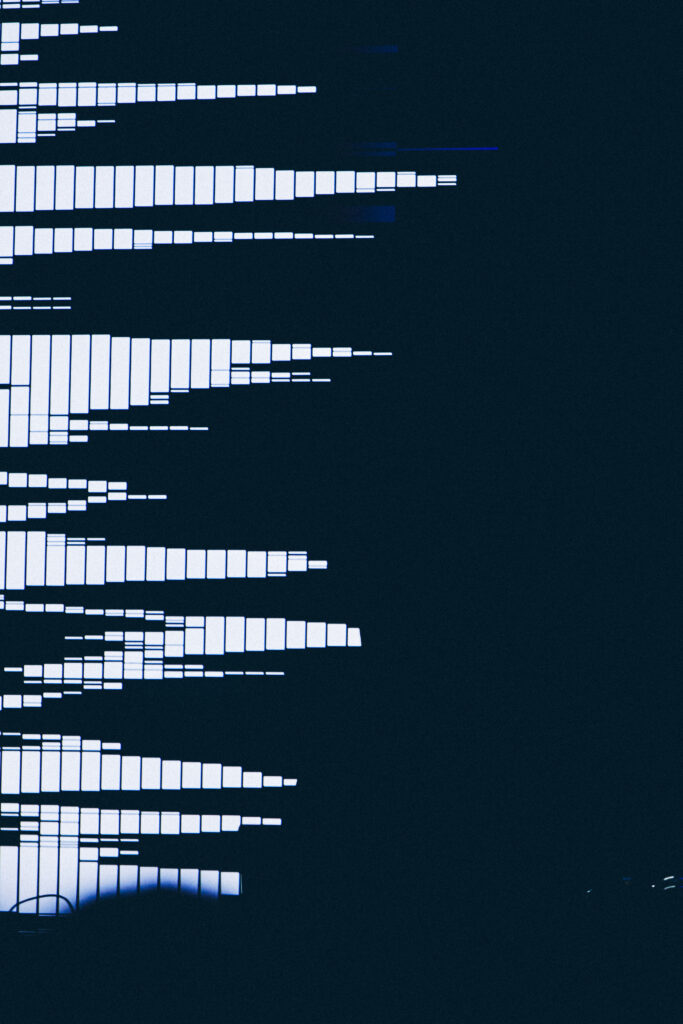

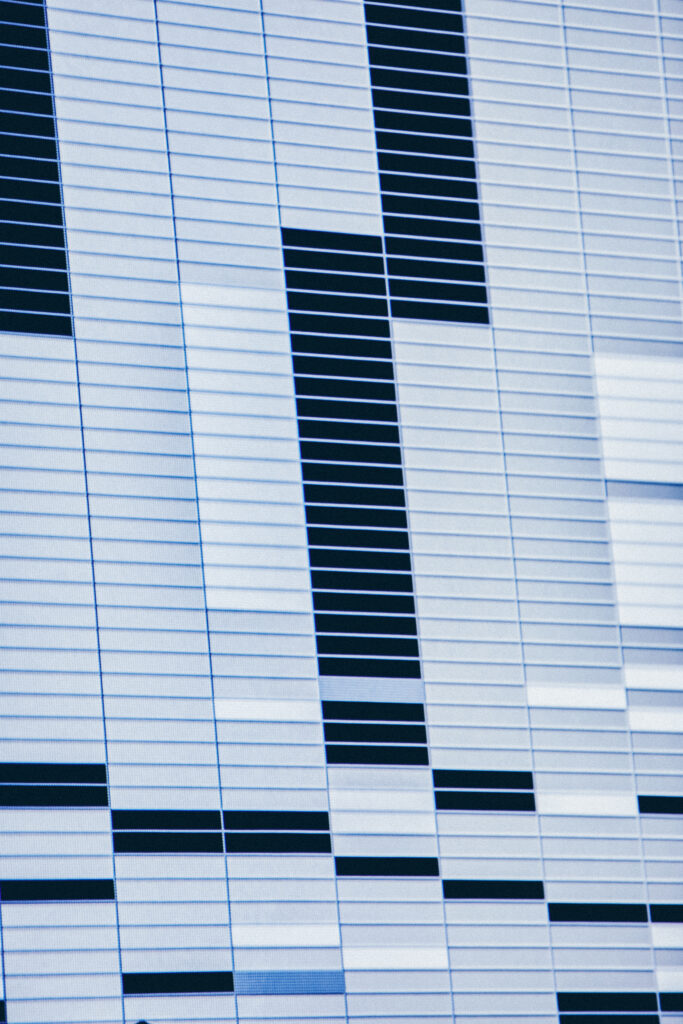

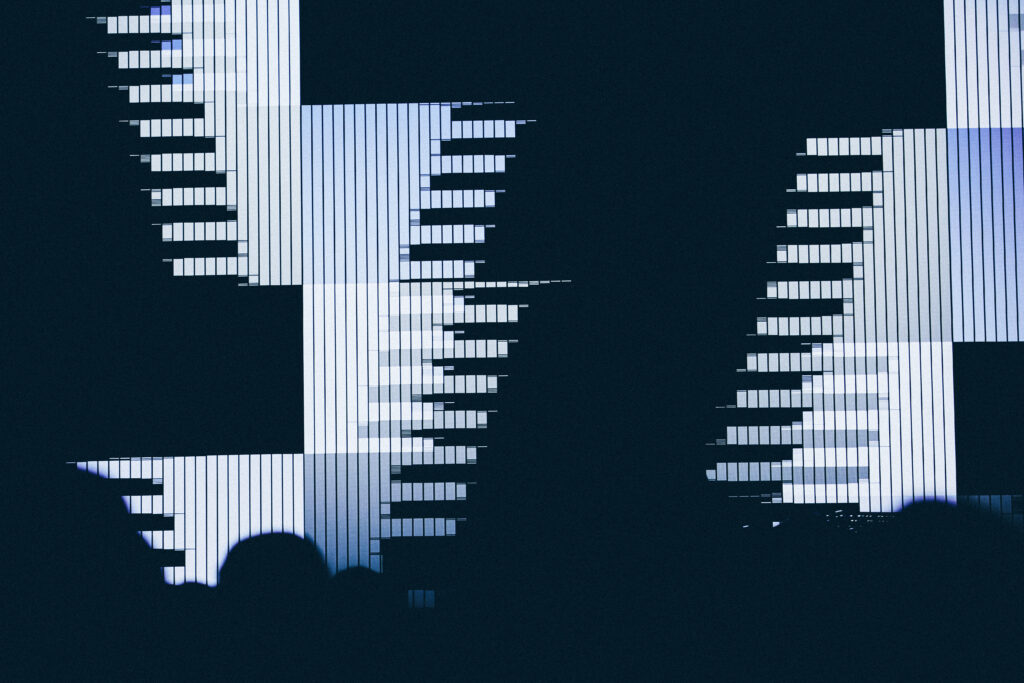

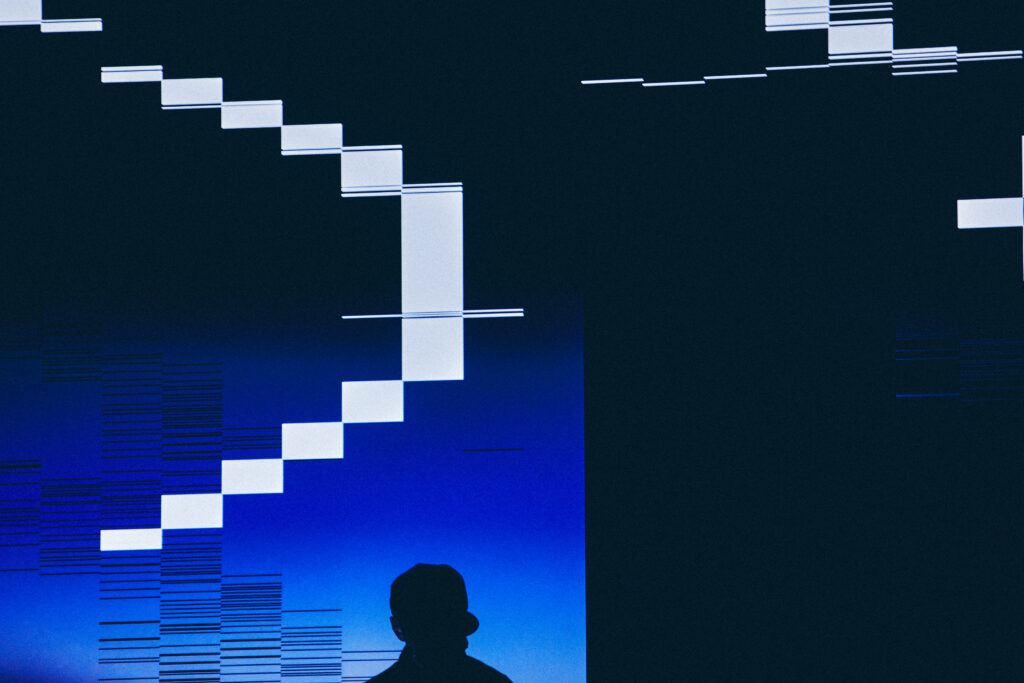

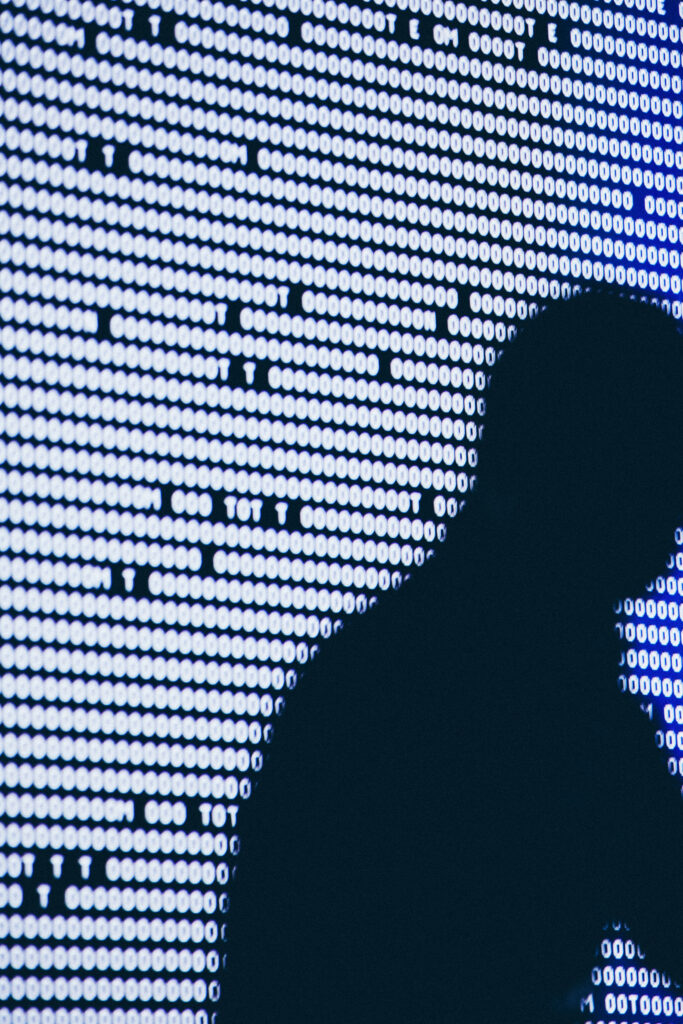

The artist first performed “superposition” at the Georges Pompidou National Center for the Arts in Paris in 2012. Within Japan, although he technically premiered it at KYOTO EXPERIMENT in 2013, it had never been shown in Tokyo before. Until recently, Ikeda performed without performers, using only motion and sound, but this time, he introduced two performers—a man and a woman—for the first time, which was a surprise. Ikeda is known for pushing minimalism to its limit, using fundamental elements, such as sine waves and white noise, in terms of sonic art. Onstage, he overwhelms and challenges the audience with a flood of images, numbers, and words, which could be described as information overload. In “superposition,” video projections and computer monitors of different sizes are placed onstage, which effectively creates a three-layered theater with the back, middle, and front. The space between the background and the middle area is for the performers. Further, by splitting the graphics shown on the screens, Ikeda produces a space packed with information alongside the feeling of time becoming fragmented.

A universe only made possible via an intense, overwhelming experience

As the title suggests, in quantum mechanics, a qubit can be in a superposition of 0 and 1. In one of the few interviews he’s given, Ikeda stated that his aim with this piece was to “present a state that even the most skilled scientist can’t explain and no one can understand” *1. “superposition” is a pure audiovisual experience and has no coherent narrative for the audience to grasp (needless to say, I’m not against works with such narratives). To use an example, it’s like the Stargate sequence in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the film, the audience’s point of view suddenly shifts to the character’s, and one experience superimposes on another. The sequence is created solely with audio and visuals; it portrays David Bowman encountering intelligent life, the birth of the universe, and the earth. It’s a sensory experience; one can’t understand it with descriptive words. One could experience and perceive similar things through Ikeda’s “superposition.” The audience receives ample information; they compute it through sounds, visuals, and vibrations. Isn’t there a realm that one can’t verbalize, is more abstract, and can only be realized through experience? The intensity of Ikeda’s piece made me consider this.

As I mentioned earlier, this was the first time Ikeda’s art included performers onstage. The two performers, a man and woman, were given roles to play as part of the piece, but they weren’t there to dance or act. The performers faced each other at a distance in the center of the stage. Through Morse code, typing, and so forth, they quoted scientists and mathematicians like Einstein, Shannon, and Poincaré. The texts were then displayed on the projection screens. It isn’t strange to assume this was a dramatic change for him. In the past, he didn’t have people typing things onstage.

Looking back on his collaboration with dancers and other performers in Dumb Type in the interview mentioned above, he said he hardly believed in the idea of human beings performing onstage. Interestingly, he’s now showing interest in the vibe that only humans have. Some might posit that he developed this notion in his later works for a percussion ensemble, like “music for percussion” (2016-2020) and “100 cymbals” (2019). But the relationship between humans and his music pieces differs from the relationship between humans and his audiovisual works. In the latter, the human has a flesh and blood relationship, which appears as an alien element.

The film captures the large screen at the back of the stage, the middle area with ten projection screens in front of the performers, and ten computer monitors in the front row head-on. As the visuals emerge from the darkness, the depth of the images initially comes across as flat, but little by little, the layers become visible. As such, the compositional beauty of the stage is pronounced. Additionally, “superposition” has been reiterated as an installation called “supersymmetry” (2014).

*1: Interview with Ryoji Ikeda (Interviewer: Kazunao Abe), Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM), 2014.

https://special.ycam.jp/supersymmetry/ja/interview/index.html

(Accessed on December 2nd, 2021)

A live show full of surprise, fun, and joy, which rejuvenates the senses

The live show was held in a different, standing-room-only venue. In the past, the artist himself never appeared onstage during his live performances, except in the early stages of his career, but recently, he’s been playing onstage. However, he’s still highly anonymous, and he keeps the factors that identify him to a strict minimum. I don’t know if this is also related to his interest in the vibe that only humans have, but it seems like he’s chosen an apt way of presenting his works, a la distinguishing between presenting audiovisuals and live music.

Ikeda has succeeded in cutting the music down as much as possible and constructing it like a geometric object. The influence of his music is immeasurable. It has birthed many artists who have followed in his footsteps, forming a particular style to this day. But even then, his work’s distinctive. I was reminded once more of this fact at his show.

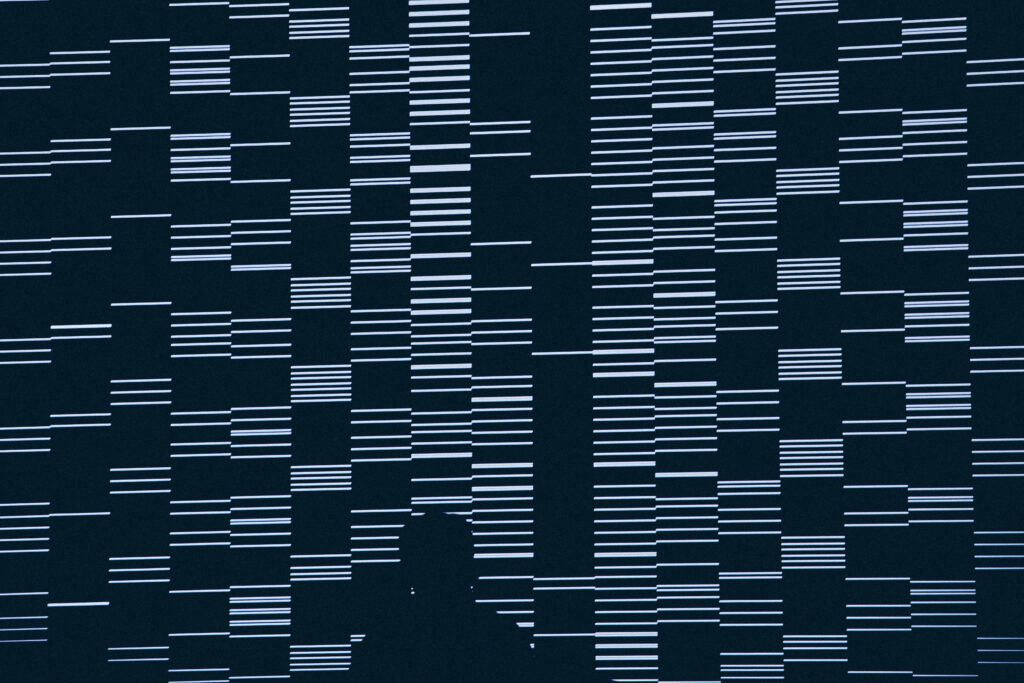

Compared to “superposition,” the monotone graphics were simple and synchronized with the sound. Instead of having a barrage of too much information, the detailed synchronization felt so good. If we trace back to Ikeda’s art, we can observe that, more than anything, they’re characterized by the fact that they never fail to deliver palpable joy. Ikeda’s art, which explores the technological potential and human sensations to the limit, is unpredictable, fun, and joyful. They rejuvenate the senses beyond logic and reflect the myriad emotions of those who experience the art. This is one of Ikeda’s brilliant characteristics, which can be seen in his installation series, “test pattern” (2008〜), where the audience could find their own way to relish the experience.

I also felt this in the second half of the show; his DJing. He played rock music that betrayed his style and public image in a good way. In his live performance, the music changed from minimalist beats to 8-beats and then to break beats. The dancefloor was filled with heightened excitement.

The screening and the live show allowed us to experience Ikeda’s diverse style; the event confirmed that these aren’t separate sides, but rather, are the very essence of Ikeda.

■『superposition [cd+booklet]』

・A 12-track CD (54 minutes) and a 96-page booklet.

・Limited edition of 999 copies with a card stating the edition number.

■『superposition 』

・The 4K film, recorded and edited from his performance at KYOTO EXPERIMENT in October 2013 (at Kyoto Art Theater, Shunjuza), is now available on-demand (for a certain fee).

*For more information, go to the artist’s official website (https://www.ryojiikeda.com/) or codex | edition (https://codexedition.com).

Ryoji Ikeda

Ryoji Ikeda was born in Gifu in 1966 and is based in Paris and Kyoto. As one of Japan’s pioneering composers and artists, Ikeda pursues the essential traits of sound and visuals through mathematical precision and meticulous aesthetics. As one of the few artists who successfully work across the spheres of visual and sonic art, his career has garnered attention from around the globe. On top of his music, he’s been involved in the “datamatics” series (2006〜), the “test pattern” project (2008〜), the “spectra” series (2001〜), the “cyclo.” project in collaboration with Carsten Nicolai (2000〜), “superposition” (2012〜), “supersymmetry” (2014〜), “micro | macro” (2015〜), and so forth. Using sound, image, material phenomena, and mathematical concepts as materials, he creates live performances and installations that immerse the viewer/listener. Ikeda continues to showcase his work at international museums, theaters, and art festivals. In 2016, he collaborated with the Swiss percussion group Eklekto on a music project called “music for percussion.” He composed music for acoustic instruments without any electronic sounds or images. They released an album together in 2018. In 2001, Prix Ars Electronica awarded him the Golden Nica Award for Digital Music. In 2014, Ikeda was awarded the Collide @ CERN Award, co-founded by Ars Electronica with CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research).

www.ryojiikeda.com

Photography Kosuke Matsuki

Translation Lena Grace Suda