The Hong Kong protests were reported daily around the world in 2019. It was the largest series of demonstrations since the return of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, with the aim of achieving five goals, the “Five demands, not one less” including the “complete withdrawal of the extradition bill from the legislative process” and the “implementation of universal suffrage”. As the clashes between citizens and police forces intensified day by day, photographer Michiko Kiseki continued to shoot the demonstrations in which protesters clashed with police and the young people who took action and appealed for freedom and democracy. Kiseki held a photo exhibition named “#まずは知るだけでいい展 [#You only need to know first]” in December 2019 to show the truth she had seen during her eight-month long stay in Hong Kong, which received a great response. She also published a photo book “VOICE Hong Kong 2019” in February this year.

Although these are reportage photos, they convey the reality of Hong Kong in a different approach from that of documentary or news photography, as is typical of Kiseki, who has been photographing famous musicians and the world of entertainment. Why did she suddenly start photographing Hong Kong protests? We sought the answer through Kiseki’s words and her powerful body of works, which definitely makes us think, “All you have to do first is to know.”

As I repeatedly asked myself why I was taking photographs, I realized that Hong Kong, my roots, was the place for me then.

–What are the components of your solo exhibition “The Place” in Kyoto, which opens on April 28?

Michiko Kiseki (Kiseki): I am planning to exhibit photographs taken in Hong Kong in 2019 and 2021, as well as a works that were shown at Gallery Niepce in February. I’m still working on the layout, though. Until now, I have not been able to exhibit the photos taken in 2017 in the other parts of Japan than Tokyo, so I made the decision this time because it will be during the KYOTOGRAPHIE, which is a perfect timing.

— There were two kinds of speculation on the internet as to why you decided to stay in Hong Kong for an extended period of time to do a series of shootings in Hong Kong in 2019. One was that you had some kind of change of heart while working on fashion and commercial photography in Japan, and the other was that you wanted to re-examine yourself.

Kiseki: Both of them are interrelated. I used to live in Hong Kong, but I grew up and became a freelance photographer without recalling it because it was a memory from my childhood. Thankfully, I was getting a good amount of work, but there was a time when I lost my mental balance while working so busily. I kept vaguely thinking about my work, my relationships, and repeatedly asking myself what I was doing photography for. Around that time, in 2016, I accompanied an artist on a tour of Hong Kong, and when I walked the streets alone during my free time, memories of my past living in Hong Kong came back to me suddenly. That made me want to remember what kind of place I lived and how I grew up, so I went back to Hong Kong in 2017 to take photos.

–Was that an extended stay?

Kiseki: Three days and two nights. It was just a light-hearted idea to go there for now.

— Was it like going to your alma mater casually when you went back to your hometown, or did you suddenly have a question when you had achieved some results in your career?

Kiseki: Yes, I didn’t go looking for answers to the questions I felt in 2016, but I guess I wanted to fill a void in my heart with something. In fact, I got a tremendous amount of power from the local people when I was shooting all over the city. Despite Hong Kong being an economic powerhouse, there is a clear gap between the rich and the poor. Even so, I was inspired by the vitality of all the people. When I began to wonder what these people are feeling in their lives, I realized how small my problems are and how small the world I had been living in is. The following year, in 2018, I was more motivated to shoot more closely into their lives, so I went to Hong Kong again. As a result, I decided to take at least six months off work and stay in Hong Kong, because I didn’t think a short stay would clear everything up. In that sense, it was due to both a change of heart and a motivation to re-examine myself.

–I visited Hong Kong for the first time in 1998, and I remember being similarly surprised by the gap between the rich and the poor. People living in high-rise apartments and people selling meatballs and other food at street stalls were all living in the same area. But what was impressive to me was that everyone was so powerful, and I could feel their “lives” in the raw.

Kiseki: I had the same feeling. At that time, I was devasted, thinking that I wanted to end my life, but I realized that it was no big deal.

— I’m sure there were many reasons for the inner conflict you had, but what exactly were they?

Kiseki: Everything and anything (laughs). It related to work and relationships. I really enjoyed shooting of the live shows and the artist photo shoots. But sometimes people would say, “Any kind of photo is okay as long as subjects are captured,” which stressed me out and made me vaguely wondered if it didn’t have to be me. I guess it was also due to a tight schedule I had at the time.

–Being freelance is not “free,” is it?

Kiseki: Yes, it really is (laughs). So, I had a moment when I felt like I was doing the work with no passion. I had always loved photography, which is why I became a photographer. Although I was not necessarily able to give 100% to everything I did, but I had a strong feeling of hesitation toward “doing something without passion,” and above all, it was disrespectful to the artists.

–Triggered by the feeling “I don’t want to hate the photographs I have been faithfully dealing with,” you reset everything once and settled yourself down in Hong Kong to renew yourself mentally, right?

Kiseki: Yes, that’s right. There were also a lot of constraints, and it is true that it was a time when those feelings were piling up.

The meaning of taking photographs has changed at the protest in Sheung Wan

–You went to Hong Kong in 2019 to get rid of those feelings. According to the official announcement, the Hong Kong Protests started on June 9, 2019, how did you spend that day?

Kiseki: I was in Tokyo that day. I was somewhat aware of the situation in Hong Kong through the news, including the enactment of the “Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation,” but I was extremely busy with work arrangements and visa issues before I left Japan for six months, so I was not able to do any solid research. I knew that I had to go there and see it with my own eyes.

–I thought that the demonstrations became more active around the time you started shooting.

Kiseki: I entered Hong Kong about a month after the protests started, but there is no doubt that it was a chaotic situation. Immediately after my arrival, I was attended by a private local guide in Hong Kong. As we walked and talked, I gradually got a grasp of the reality of the situation, and then he asked me, “Would you like to come to the demonstration on Sunday?” By witnessing it firsthand, I gradually understood what was going on.

— At the time, could you have anticipated that you would be taking such in-depth photos of the demonstrations?

Kiseki: The demonstrations were peaceful in the early days after we arrived, but the situation was becoming serious day by the day. The first demonstration I saw was in Sheung Wan on July 28, and at that point it had become quite radicalized. Tear-gas granades were flying everywhere, and the area was a complete mess. I witnessed young people being beaten and arrested right in front of me. Anyway, it was shocking. The smoke from the tear gas made it difficult for me to breathe, and I had to be rescued by an aid person. But I started working on more in-depth shooting.

–In that context, you were unexpectedly plunged alone into a serious vortex of protests. But when I read the text on the belly band of the photo book VOICE Hong Kong 2019, I got the impression that you were taking photographs in response to the words you heard from the people you met. Naturally, the tension must have increased, and I think the meaning of shooting changed as well. Am I right?

Kiseki: I myself was born and raised abroad, but I don’t speak English. So during my stay, I went to an English language school in the morning and went out to shoot demonstrations in the afternoon. But with the language barrier and the frequent demonstrations, the first month was a totally mess.

The demonstration in Wan Chai on August 31st was the one that changed my mind about shooting. I will never forget it. At that night, in the midst of many police officers and protesters, a boy next to me grabbed my arm just as he was being arrested and shouted, “Help!” But I couldn’t do anything. At that time, journalists had to ask for names and Hong Kong IDs of those who were arrested to see if any of those people would be later released. I really felt my helplessness. All I could do was to shoot and transmit the information, but since then I started to wonder what it would bring and what help it would lead to. While I was asking around to Japanese media and acquaintances, a friend of mine from elementary school sent out an SOS. At first, the two of us spread the hashtag “#まずは知るだけでいい [#You only need to know first]” on Twitter and opened a new Instagram account to pick up the words of each and every person in the area.

–What were you doing during the clashes between protesters and police at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University on November 17, 2019?

Kiseki: There was a big clash at CU before that, and I couldn’t go because I was far from home, but I had heard some Hong Kong Polytechnic University students saying that they would defend their university, so I knew something was going to happen. The demonstration was a standoff with the police force, bordered by a bridge in front of the University, and when a fire bottle thrown by one student hit an armored car and caught fire, the Hong Kong police issued an order to arrest everyone on campus for “riot” charges. I didn’t understand the language and local information was not immediately available to me, but I received tons of calls and emails from friends telling me to leave immediately if I was at the Polytechnic University, so I rushed to the exit and was released after the most rigorous checks imaginable.

Deep-rooted social issues and complexly intertwined local sentiments.

— It’s an unbelievable situation. In your photo book, I think what you want to convey is tied to the words of the local people, what kind of interactions did you have with them?

Kiseki: There were not always violent clashes going on in the streets or on campus, so I walked around and talked to all kinds of people and picked up their words.

–Are there people with whom you have become more connected because of the demonstrations?

Kiseki: Most of my friends in Hong Kong now are people I met at the demonstration, and we still keep in touch.

— Can you tell us about the most dangerous moment during your stay in Hong Kong?

Kiseki: When I was leaving the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, I was worried that I might be detained and when I was hit by a tear-gas granade.

–The fear of being detained is immeasurable.

Kiseki: Yeah, I strongly felt my life was in danger.

–Although you have lived in Hong Kong for some time, you were not a party to this issue, were you? I wondered what motivated you.

Kiseki: I saw young people being beaten up and arrested, which is something I have never seen before, but the actual problem is much deeper than that. In addition to their harsh living conditions, as exemplified by their housing and labor problems, they also complained about the lack of respect for their identity as Hong Kong people. I don’t want you to get me wrong, but as a photographer, I honestly wanted to know the background of this issue and my curiosity was aroused. I also feel that I was motivated by their feelings more than that.

Another thing was that I was confronted with the fact that I had been living in ignorance and indifference until then. While I felt a stronger desire for Japanese people to know about Hong Kong, I also felt that I had found the significance of photographing the people living in Hong Kong who are doing their best to preserve their lives.

“I don’t want to give out specific answer for photography, and I still want to take photographs that are not consumed.”

–I know your photo book the STRONG will in Hong Kong is all in color. Could you tell us why VOICE Hong Kong 2019 is in black-and-white?

Kiseki: I had made all my works in black and white except for client work, so the STRONG will in Hong Kong is my first photo book in color. The reason is simply related to the power of information transmission that color photography has. In contrast to the documentary aspect of former, in which I wanted to convey the current situation, I think of VOICE Hong Kong 2019 as “memory.” Photography is a medium that can contain both memory and record, and recently I feel that color photographs are about recording and black-and-white photographs are about memories. I chose to use black-and-white for all the photographs to preserve the memory of Hong Kong, an event that happened two years ago. Because black-and-white photographs contain less information, there is more room for the viewer to ponder, pause, and imagine. I can also learn from their imagination. In that sense, I think my experience in Hong Kong even changed my expression as a photographer. Color is better for those who want to convey detailed information accurately, but in this work, I did not want to give an answer as much as possible. I would be happy if, as you look at the photos, you could imagine the color and location of something in the images, rather than the story completing itself on its own. I want people to just get to know it first, and beyond that, I want to leave it up to the viewer to decide what he or she thinks about it.

–You also stayed in Hong Kong at the end of 2021. What kind of changes did you feel from the photographer’s point of view after COVID-19?

Kiseki: Everything that we couldn’t see had changed. Of course there were changes due to the impact of COVID, but I hear that there are people living in Hong Kong now who cannot move overseas due to economic or language reasons. I was overwhelmed by the power of people who remained positive while accepting the current situation.

–The text in the photo book says “struggling.” Is this word “struggling” synonymous with the “living”?

Kiseki: I think so. However, it is not literally “fighting.” There are various non-violent ways to struggle. There are those who use words to struggle against something, and there are those who struggle for enduring something without showing it.

–Anyway, continuing to live is also a struggle, isn’t it?

Kiseki: It really is. In that sense, that sort of realization must have been the source of the power of the local people I felt in 2016 and 2017.

–Like the issues in Ukraine, I think that even if people take action against unreasonable power, it is mostly the citizens who suffer the backlash or have a hard time. What do you think photography can do and what do you think is the power of photography under such circumstances?

Kiseki: First of all, what I felt from my experience in Hong Kong is that history repeats itself. I think it is important to archive the facts and pass them on to future generations. While there are a variety of mediums with different characteristics as a means of conveying information, photography should function as a medium that remains in the memory without being consumed, rather than transmitting vast amounts of information one-sidedly.

–Video footages can be arranged in arbitrary sequences, making it easy for the creator to guide the viewer. Photographs, on the other hand, capture what happened in a moment as it happened. You can make it arbitrary by adding captions, so it’s basically the viewer’s thing. In the sense that it can show the facts of the past, I think photography is an excellent medium.

Kiseki: Photography has a documentary aspect, but I think memory is a major factor of it. Various people imagine the thoughts of the subjects, and the memories from when I photographed them overlap with them. When I talk with visitors to my exhibitions, I feel helpless, but I am also encouraged by the fact that I was able to give them an opportunity to think about such things. I believe that the repetition of these acts is a meaningful experience for me.

–What kind of activities do you hope to pursue in the future?

Kiseki: I will probably shoot in the context of commercials, documentaries, and journalism, and there may be food and animal photography there. A lot of my past client work has been music-related, and I have a lot of experience being helped by music. Music is great. Certainly, my experience in Hong Kong may have been a turning point for me as a photographer, but it increased my experience in photography up to that point. I still don’t want to give out specific answer for photography, and I still want to take photographs that are not “consumed.” Also, I don’t want to categorize my photos into any kind of types. I want to be honest about my original desire as a photographer, which is to take pictures of what I want to take pictures of.

Michiko Kiseki

Born in Belgium, Kiseki later spent time in Hong Kong and France. Graduated from Nihon University College of Art, Department of Photography, she worked at a photography studio and as an assistant before going independent. She has worked as a portrait photographer for various artists including Brahman, The Yellow Monkey, and Sonar Pocket. For 8 months from July 2019, she stayed in Hong Kong to work on her series of works, and in February 2022, she published a photo book VOICE Hong Kong 2019, which captures a series of protests that continued for about 6 months, triggered by the proposed amendment of the ” Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation,” and the people living there. Since returning to Japan, she has continued her activities as a freelance photographer, focusing on music and documentary photography.

www.kisekimichiko.com/

Photography Michiko Kiseki

Interview Hiroyuki Watanabe

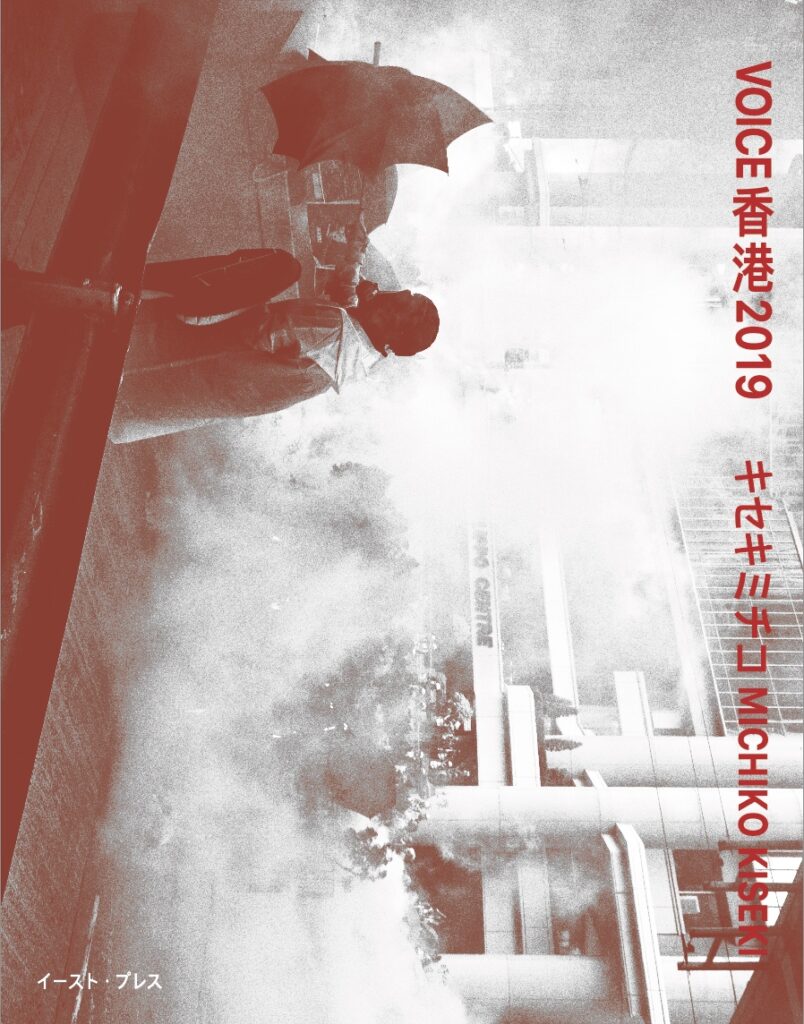

■VOICE Hong Kong 2019

A photo book by photographer Michiko Kiseki that captures the frontlines of Hong Kong protests in 2019 and the people living there. Price: ¥6,600.

www.kisekimichiko.com/shop

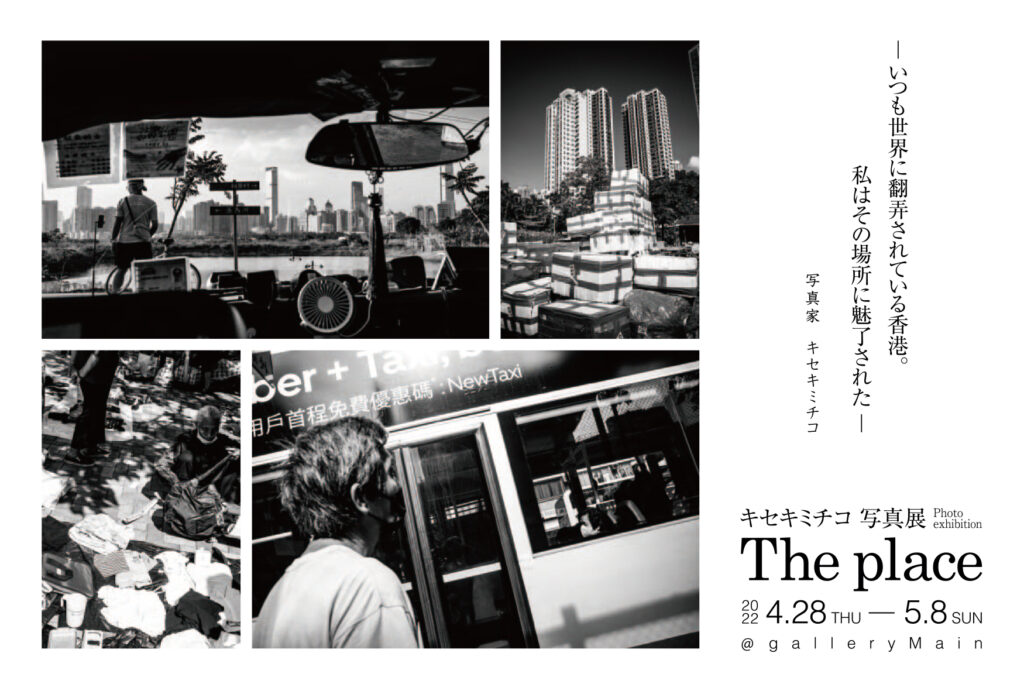

■The place

Dates: April 28 – May 8, 2022

Venue: Gallery Main

Address: 2F, 543 Shimourokogata-cho, Gojo-agaru, Fuyacho-dori, Shimogyo-ku, Kyoto-shi, Kyoto

Hours: 13:00-19:00 (18:00 on the last day)

Official website: https://gallerymain.com/exhibiton_michikokiseki_2022/