I met the organizer of the event, Pablo, by chance. He told me repeatedly, “We continue living normally; it doesn’t matter if we’re in a war.”

Following my visit in March, I went to Ukraine, which has been under invasion by Russia, for the second time. I reported on occupied villages and cities destroyed by the Russian troops, like Kharkiv and the surrounding areas of the capital Kyiv. My previous stay was for a month, but I stayed for three weeks the second time. With only a few days left, I headed towards Odessa in the south of Ukraine. It looks out onto the Black Sea and is an important area with the largest port within the country. Because of this, the Russian troops are intensely targeting Odessa from sea and land. Although there haven’t been missile attacks in the city center, I saw on the news that the troops have bombed numerous shopping malls and hotels, leaving behind casualties. Further, Odessa is also known as the pearl of the Black Sea and is a prominent vacation spot with historical buildings and beaches with white sand. I felt it was an enticing place to visit last to take photos.

But the reality was harsh. I certainly sensed a touristy vibe from the cobblestone streets and historical architecture, but there were almost no foreign visitors because of the war. The city stood still. Even to this day, on the white, sandy beaches lined up with holiday homes are signs saying, “Beware of land mines,” an effort to prevent the troops from coming ashore. One can say the reason there are so many signs banning photography all over the city is that the Ukrainians don’t want vital militaristic information, such as the city’s landscape and terrain, to be leaked. Like Kyiv and Kharkiv, air-raid alarms go off countless times per day. I eventually felt dreary and walked around the city in a sad mood.

Meeting Seva serendipitously

Suddenly, a young man asked me where I came from when we walked past each other. His name was Seva, a 19-year-old local student with a canvas and aspirations to make a living as a painter in the future. “I’m carrying a drawing I just did right now. Do you want to walk and chat with me?” I followed him for a change in mood.

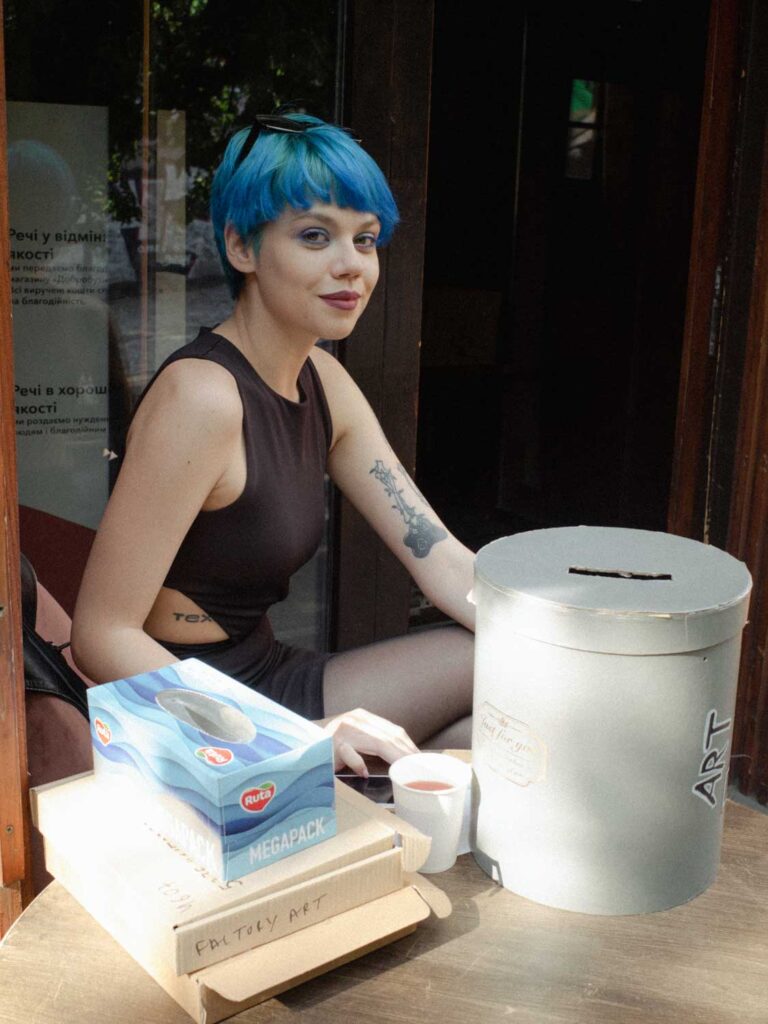

We arrived at the back entrance of an ordinary-looking housing complex. Once we went through the door, we came across a renovated art space that used to be a warehouse. It was initially run as a club but is now closed after martial law was declared after Russia’s invasion. One of the primary members, Pablo, told me they’re temporarily using it as an art space and are exhibiting artists’ works. Seva’s work was one of them.

According to Pablo, the community is managed by members from different occupations, such as café staff, hairstylists, and musicians. They host events from time to time to raise money and donate them to volunteers.

He invited me, “We’re throwing a party this Friday. Do you want to come?” Sadly, I had taken all the photos I needed and had to go on a train to Poland that Friday evening. I explained my situation and told him I’d stop by in any case. Then we parted that day.

The day of the party. I went through the backdoor of the housing complex and saw that Pablo was setting up the DJ booth in the courtyard. They were throwing a small rave and were using the courtyard as a dancefloor. From there, I could see the blue sky. It felt good. The other organizers were getting ready for the party with excitement too. Maybe it was because we were in Ukraine, but many flowers were on display. “The event’s until 9 PM. You can’t go outside past 10 PM in Odessa, so this is a brief, fun moment,” Pablo said, laughing.

After a short while, music started blasting from the speakers. Some of the organizers took their place on the dancefloor and began dancing. I felt a bit bewildered seeing people dance in front of a DJ in Ukraine during the war. Pablo looked at me as though he saw through me and said, “You think this is strange, don’t you? I understand. But we continue living normally; it doesn’t matter if we’re in a war.” I decided to extend my stay in Odesa by one day right away. I wanted to witness the situation for a little longer.

Once it was past 3 PM, people gradually started to come in. Dressed up to the nines, people would hug, dance, and enjoy themselves. They were all friends of the party organizers or friends of friends. Partially due to the organizers not promoting the party too much, there were about 15 people. It might not sound like a lot, but to begin with, Ukraine is under martial law. Perhaps that scope was the limit, but they were undoubtedly having a good time.

The DJ mostly played techno, but some songs were city pop-ish. There was a song with a very catchy melody, and a girl in the crowd was singing along. I went up to the DJ because I wanted to know the name, and he told me it was a remix of a well-known Russian song. He looked it up on my phone immediately. I was stunned as I realized they were dancing to the enemy’s music during wartime. That’s how deeply embedded Russian culture is in Ukraine, and it reminded me of how it’s not a clash of cultures and customs but rather a one-sided invasion.

Carrying on as usual during wartime

I headed back to the backdoor to rest. I stepped outside and saw the city deserted as usual and could hear the faint rhythm from the other side of the door. Who would ever imagine people having a party in such a place? Part of me was happy to be at a secret party.

After I had a breather, I heard an ominous sound; an air-raid alarm. I opened the door and ran back inside. I was surprised again, as everyone was still dancing with all their might. Sure, the venue was loud, and no one could hear it. But you get notified on your phone, so everyone must’ve known about the alarm. Some people looked at their phones, put them back into their pockets, and went back to dancing again. No one stopped dancing under the sky with air-raid alarms. I finally understood what Pablo meant when he said they continue living normally.

I asked Pablo, who was fixing the sound, what normal meant to him. He replied swiftly, “To have fun in any situation. You get it, right? You always take photos. And you probably do that in any situation. Likewise, I meet my friends like this and have fun listening to music. That’s normalcy for me. I continue doing it.”

According to him, they spent March and April not doing much because of martial law. But they got tired of that and began hosting parties every Friday starting from May. For those of us who live in peaceful countries, it might seem unusual for people to dance in wartime. But that’s from the perception of the outside. Being invaded was an abnormal experience for them, as they danced every day until the war started. So, they can’t discard their source of happiness even if alarms are going off.

My eyes met with a young man named Yuri, a local rapper. He rapped in Ukrainian on the spot along to a fast electronic track. I couldn’t understand what he was rapping about, but he told me his thoughts: “When the war started, everything became dark. So many people in this country lost their families because of it. Everyone’s hearts are hurting. I wouldn’t say that’s why we do this, but my friends and I talk about our dreams when we meet. That alone is fulfilling. I think I’ve become a bit optimistic.”

I then realized Seva, the painter, was nowhere to be found. When I went outside, I saw that he was hanging out with other young people in front of the entrance. “Listen, I can’t go inside because I’m on the blacklist for some reason,” he said with a small smile and shrugged his shoulders. He got into a minor quarrel with another member the other day. But Seva wasn’t the type to hold a grudge, so he was enjoying his reunion with other friends outside the venue.

The youth keep on dancing

In Ukraine, the sun sets late. It finally started to set around 8 PM. The DJ said something over the mic in Ukrainian, and one of the people in the crowd told me, “This is the best part!”

Two more hours until curfew. Perhaps we were close to the peak of the night. More people started arriving, making the total count about 30. The crowd moved to the beat with glowing expressions on their faces. Some would chug their drinks and let out a yell, but that was charming. I couldn’t help but smile too.

“I’m so glad I decided to stay for another day. I’m so happy I could be here,” I said to Pablo. He replied, “I’m glad to hear that. It’s not like us to be gloomy and do nothing just because we’re in a war. We do our best to have fun. That’s our normal.”

He put on a brave face, but I’m sure a part of him was frustrated because, without war, they would be dancing until morning. It’s already been three months since the invasion, with no signs of a ceasefire.

There wasn’t much time left until curfew, but the youth continued to dance while air-raid alarms went off.

Photography Hironori Kodama

Tlansration Lena Grace Suda