As the 62nd Grammy Award nomination of the compilation album Kankyo Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990 (2019) illustrates, Japanese environmental music of the 1980s has recently made a comeback. Satoshi Ashikawa, who passed prematurely in 1983 at the age of 30, was someone who had made a mark on the world of Japanese ambient music. While incorporating contemporary music and Murray Schafer’s theory of Soundscapes, he created his own “music as a landscape.” Not only did he create serene and discreet music, he designed sounds that could be utilized effectively in everyday life, and started his company in 1982. A tragedy occurred the following year after he started his company Sound Process Design. After Ashikawa’s passing, Munetaka Tanaka took over the company and continued Ashikawa’s legacy, working on sound design for cultural, commercial, and transportation facilities. One of the sound designers on those projects was Yutaka Hirose.

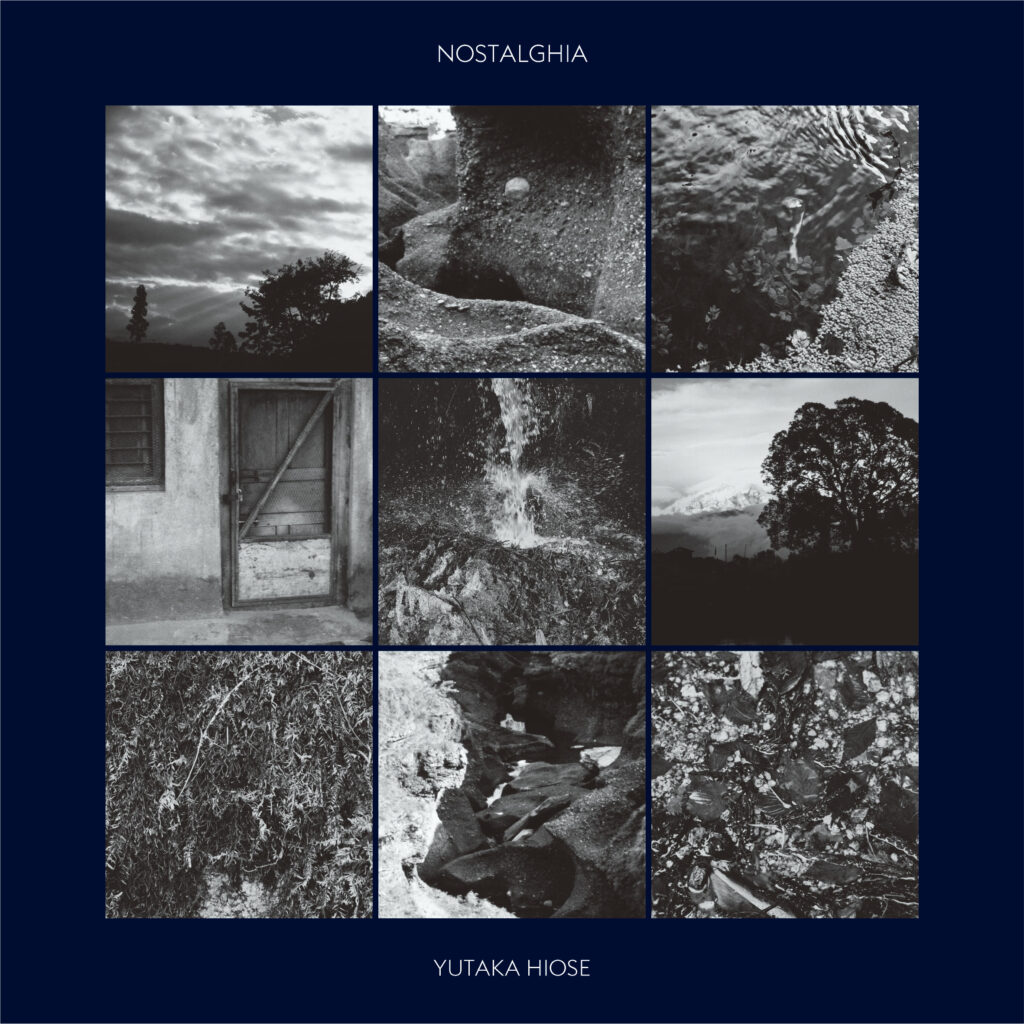

In 1986, Hirose released Nova, the only musical album to come out of the Misawa Home Sound Design Research Lab’s “Soundscape” series. Although the record remained out of print for a period, Hirose assisted with the resurgence of ambient music, and re-issued the record with bonus, previously unreleased recordings on the Swiss label We Release Whatever the Fuck We Want, in 2019. The re-issue of Nova, a record that holds as much significance as Midori Takada’s Through the Looking Glass (1983) and Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Music For Nine Post Cards (1982), amassed a great deal of attention. Now, Hirose has completed his second album Nostalghia, his first in 36 years.

Nostalghia is an album made up of two LPs, including one CD with seven tracks and another with nine. The album includes recordings based on works created after the release of Nova and newly edited versions of environmental sound designs recorded between 1987 and 1991. Thus, this work is a combination between a valuable archive and a brand new musical release. In part one of this two-part interview, Hirose speaks about the changes in his creative process post-Nova, and his background in free improvisation and free jazz.

From notated music to improvised production

– The recordings in Nostalghia were recorded from 1987-91, after the release of Nova in 1986. What was your objective for those recordings back then?

Yutaka Hirose: They were initially created for stereophonic sound. I wanted to build sounds based on space rather than do something musical. Nostalghia was created from two left and right channels. But at the time, the sounds were built from eight unmixed channels with disparate sound sources randomly playing in history museums and science museums. The sounds were intended to be constantly changing, and were to be played at specific facilities. I had no intention of listening to it in stereo back then. I ended up creating a two-channel mix solely to keep a record of it.

– Nova was released as a part of “Soundscape,” Misawa Home’s environmental music series. The concept was to make music to play in a specific environment. How do your new record differ from Nova?

Hirose: For Nova, we used sheet music and input each note into a computer. Afterwards, during the mixing process, we added environmental sounds to build atmosphere. But in Nostalghia, I didn’t use sheet music or input anything into a computer. Instead, I added notes improvisationally. For example, I recorded a number of melodies and phrases that I played improvisationally, and designated each sound lump a “group.” I used each “group” and composed them as if I were splicing them together.

– Why did you change your approach?

Hirose: I’ve always liked improvisational music, but it also took a lot of time inputting notes into a computer. So much so that I thought that would be all I would do for the rest of my life (laughs). I thought it would be faster if I played the notes myself then selected and spliced the notes together afterwards. There was also more freedom that way. Instead of pre-selecting notes by writing them out, this album was created much more freely by playing the sounds, combining notes that I thought would fit together, adding effect A to one and effect B to another, then splicing and shifting them.

In Nostalghia, I wanted to focus more on the sounds themselves rather than melody. Since people have a tendency to get caught up by a melody, my intention was to create a sound organically. I wanted be able to hear the sound objectively, to let it speak directly to people’s souls, or to create a space in which people can enter into the world of sound.

– Was being able to create interesting tones an advantage of creating music improvisationally?

Hirose: Yes. I usually lay down the foundation of my work first with low end and keep adding layers of harmonics until I end up with high end notes. If you think about that, it’s important to consider how those tones are created, and how they affect my playing. My playing is influenced by the tones I hear. In other words, the timbres of the sounds lead where the music goes. If you start inputting that into a computer, it has to be notated properly which then makes it difficult to come up with interesting tones. Instead, the instrumental elements tend to come to the fore. Even synthesizers end up sounding like instruments. I wanted to try something else for it to not end up that way, which is how I ended up improvising.

Being influenced by Derek Bailey’s tone in his teens

– You mentioned earlier that you’ve “always liked improvisational music.” Which musicians did you like specifically?

Hirose: I’d say I liked most of the music released on Incus records. I listened to artists like Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, and Tristan Honsinger a lot. And Anthony Braxton. I listened to Bailey’s Lot 74 – Solo Improvisations (1974) in my teens, and even went to the MMD trio (Min Tanaka, Milford Graves, Derek Bailey)’s 1981 performance in Japan.

Bailey’s shows were extremely interesting. He opened my eyes to different uses of harmonics. It was really fun to watch him play. I could enjoy his music sincerely since my first listen, without ever rejecting it. A while after, Evan Parker came to Japan and had a great show at the Nippon Seinenkan Hall in 1982. I could listen to his circular breathing sax solos forever; it was so satisfying to listen to. There was barely any audience there, though (laughs).

– Have you ever felt there were ambient elements in Bailey’s music?

Hirose: His tone was so captivating. To me, his nonlinear approach to improvisation felt more ambient than chaotic. I never really listened to ambient music, though. I started listening to ECM in high school and grew interested in free jazz after that.

– ECM was created in 1969, and represented artists like Bailey who created eccentric works. They continued to build an aesthetic label/sound throughout the 70s. Did you like the works from that era?

Hirose: I liked Bailey and Dave Holland’s duo record Improvisations for Cello and Guitar (1971) and Paris Concert (1971) by Chick Corea’s jazz group Circle, which Braxton was a part of. But within ECM, I actually really liked Eberhard Weber, Steve Kuhn, and the like. I loved their sound, and simply thought their music was pretty.

Most ECM works are not very lively, meaning they work in spatial settings, as well. You can listen to it naturally, you can listen to it as sounds, and you can enjoy it without putting emotion into it. You’re able to enjoy the music in different ways because there’s no specific climax to the music. The way I listen to sounds is more free, and has changed dramatically through my exposure to ECM.

Being conscious of the free jazz structure during the creative process

– In Nostalghia’s liner notes, Toshiya Tsunoda writes that the record was “conscious of the free jazz structure.” What specific structure was that referring to?

Hirose: The first song, “Seasons,” is the most obvious example. Most of its structure is free jazz, and is mostly improvisational. There are a bunch of detailed elements scattered throughout. It’s made to not repeat the same thing from start to finish. Some good examples with similar structures are Albert Ayler’s New York Eye and Ear Control (1966) and several of Don Cherry’s albums.

I also like contemporary music even more than I like improvisational music, and listen to artists like Iannis Xenakis and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Stockhausen came up with a technique called “group composition.” Instead of keeping track of individual sounds via total serialism, you utilize different groups of sound by scattering them and tracking their changes. Instead of categorizing structures of individual sounds with serial composition, it categorized things into groups and scattered them. I talked to Mr. Kakuta about how we were conscious of that sort of approach and of other free jazz structures.

– Speaking of free jazz, you often mention that you like Masahiko Togashi’s albums and listen to them a lot.

Hirose: That’s true. When I was reading Swing Journal, I thought I would try listening to Japanese jazz as well, and not just Western jazz. The record I stumbled upon first was Mr. Togashi’s. I used to listen to Spiritual Nature (1975), Guild For Human Music (1976), and Essence (1977) a lot. Mr. Togashi’s music is very Eastern, very Japanese. That caught my eye, and I got really into the drumming and percussion elements of his records. They sounded like falling water droplets; it was very comforting to listen to.

– How about Japanese free jazz musicians like Yosuke Yamashita and Masayuki Takayanagi?

Hirose: I used to listen to Yosuke Yamashita. But I never got to Masayuki Takayanagi back then. As far as I know, none of it was even playing on the radio. I just listened to the music that I happened to stumble upon.

– How about people in the 1980s, musicians like Masabumi Kikuchi, Yoshio Suzuki, and Yasuaki Shimizu, who incorporated ambient sounds from a jazz perspective?

Hirose: I didn’t know them back then. I never encountered them.

Yutaka Hirose

Sound designer. Born in 1961 in Kofu City, Yamanashi Prefecture. Released album Nova as part of Misawa Home’s Sound Design Research Lab series “Soundscape” in 1986. In the same year, Hirose joined Sound Process Design, a company started by Satoshi Ashikawa, and worked on the sound design for projects in several cultural and commercial facilities. In 2019, Hirose re-issued Nova. Released by Swiss label We Release Whatever The Fuck We Want, the record included a bonus track with unreleased recordings and gained worldwide attention. In May of 2022, Hirose released Nostalghia, his first album in 36 years. Hirose plans to release Trace Sound Design Works 1986-1989 with the same label on July 1st.

Translation Mimiko Goldstein