Ambient music was initially a concept proposed by Brian Eno in 1978 as an ambience that highlights the uniqueness of the environment in a particular space. Now, the term is used ambiguously to refer to music with a minimalist and peaceful sound, and can include everything from electronica and background music to environmental music. While Eno’s music communicates an image without invoking a clear concept in the music itself, an innocuous effect of the resurgence of ambient music in the 2010s is that by reinterpreting sounds designed solely for environmental music as a part of ambient music, it can now be enjoyed as a musical piece rather than as a purely practical piece. I believe the value of Japanese environmental music is being rediscovered in the same way.

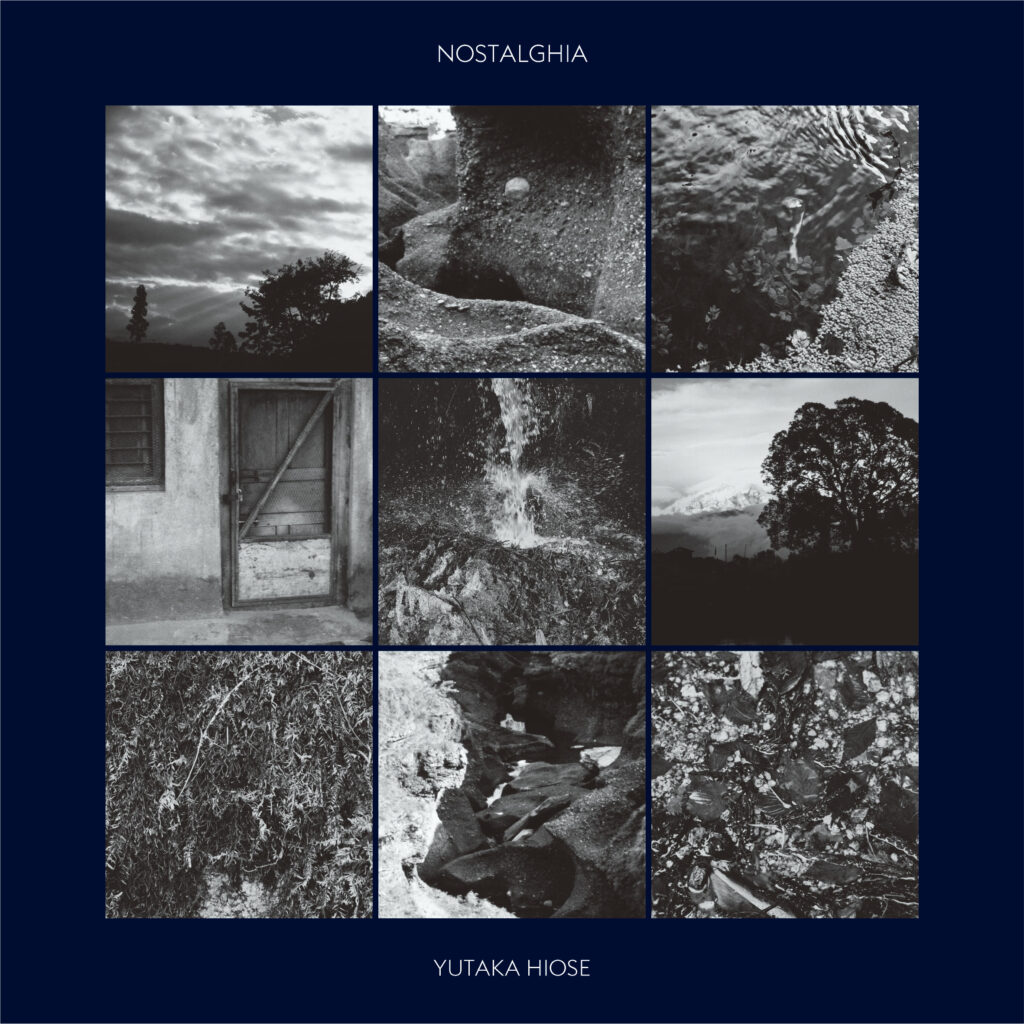

It could also be said that the significance of sound designer Yutaka Hirose’s second album Nostalghia, his first in 36 years, has been newly discovered through this trend.The recordings used in this album were originally recorded from 1987~’91 to be used to play in public facilities. Since Hirose himself repurposed and “musicalized” those recordings to create this record, Nostalghia has been redesigned as contemporary music. In addition, although the album itself is not intended to be played solely in a specific space, each song on the record is presented for a separate space. – It feels unnatural to call this ambient music.

Originally, there were seven CD’s worth of previously unreleased recordings. With the help of music supervisor Tatsuto Inoue of Fushigi Ongakukan and artist Toshiya Tsunoda to select the songs and with musician Taku Unami mastering the record, Nostalghia finally saw the light of day. The finished product not only sounds unlike ambient music, but also sounds alien to Japanese environmental music. In the second half of this two-part interview, Yutaka Hirose speaks about Brian Eno, Sound Process Design, Nostalghia’s “fear,” and coming up with the term “Japambient.”

The changing image of Brian Eno

– When did you first come across Brian Eno’s music?

Hirose: I first learned about Eno when I had just started middle school. At the time, I was listening to his Roxy Music era and his early vocal albums, which is why he gave me a strong glam rock or prog rock impression. That was my default image of him, which is why I was confused when I first heard Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978). The Japanese version of Discreet Music (1975) wasn’t released until the 80s, so my first encounter with Eno’s ambient works was Music For Airports.

It was Ambient 4: On Land (1982) that changed my image of Eno. I was wildly impressed. Unlike Music for Airports, there’s life in On Land’s sound. Featuring several musicians like John Hassell, the sounds on that album are as colossal as the Earth’s foundation. I was in complete awe.

– How did you perceive that type of tranquil music before Eno popularized the term “ambient music”?

Hirose: Although the term “ambient music” wasn’t used, music that sounded similar existed. Terry Riley’s In C (1968), Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells (1973), Steve Laihe’s Drumming/Music For Mallet Instruments, Voices And Organ/Six Pianos (1974) were some examples of minimalist music. Riley had been using tape loops since the 60s, so the technique used in Eno’s Discreet Music wasn’t all that new. The key was that Eno introduced “ambient music,” a different, new, unique style of music.

I was more interested in the Obscure record series over the ambient series. I was heavily influenced by Gavin Briars’ use of strings and acoustics in The Sinking of the Titanic (1975). The concept of the Obscure series was to promote experimental music. Eno was bringing contemporary and experimental composers to the forefront as a producer. I think his experience doing that morphed into the ambient series.

Working at Sound Process Design

– You got to know Satoshi Ashikawa right before his death in a tragic car accident in 1983. You even brought your own tapes to Sound Process Design, the company which Mr. Ashikawa built.

Hirose: I met Mr. Ashikawa when I went to the Harold Budd concert in Japan (1983), which he organized. I listened to Harold Budd’s music on records before, but this was the first time hearing him live. I was intrigued by his unique sound, and that led to listen my listening to Mr. Ashikawa’s records. Afterwards, I thought it would be nice to give Mr. Ashikawa a gift when I met him again, so I brought my own tapes.

– What was most appealing about Mr. Ashikawa’s music?

Hirose: Probably how he forms his music around singular notes and silences. Mr. Ashikawa’s Still Way (1982) uses harps, pianos, vibraphones, and other instrumental components to create singular notes, or points, in his music. I think that’s how it differs from Eno’s ambient music.

– After the release of Nova in 1986, you made music to be played in different science and history museum spaces and other facilities as a part of Sound Process Design. What was the reaction to that type of music back then?

Hirose: It was only meant to be used for the museums, so I didn’t get any direct feedback. I just kept doing my job.

– Since the 1990s, the term “sound art” has been used to refer to the presentation of sound in spaces. How did you feel about such trends?

Hirose: I had stopped making sounds after the 90s. I was no longer listening to trends, let alone hopping on them. Maybe it’s because I moved out of Tokyo, but I had cut off all information.

Echoes of “nature = fear” in Nostalghia

– You could’ve exhibited these works as sound installations, but instead, you created an album. Why did you choose to release Nostalghia in CD and LP formats?

Hirose: In 2019, I reissued Nova with We Release Whatever The Fuck We Want. After that release, I was approached by a lot of people asking me if I would want to release an album of my unreleased tapes. Considering my age and the possibility of death, I decided to put out an album of things I worked on from my late 20s. I obviously didn’t want to release anything as is, so I processed and edited it a bit, and added my present self into it. I was especially particular during the mastering process, which resulted in the final product.

– The mastering was done by Taku Unami, correct?

Hirose: Yes. We actually changed the mastering a couple times. We had a more aggressive master and a more quiet master. The aggressive master sounded too metallic and harsh, so upon discussing it with Mr. Unami and Toshiya Tsunoda, we decided on what you hear today.

– In recent years, we’ve seen a new age revival and a resurgence of ambient music. Through that trend, Japanese environmental music has been getting rediscovered abroad, and has been getting reimported into Japan. You could say that environmental music that was meant for soundscapes is now being redefined as ambient music. How do you feel about your music, that was initially created to be heard in specific spaces, being listened to as ambient music?

Hirose: I released it intending for it to be a spatial music album. In the LP, all nine songs are meant for nine different spaces. Nostalghia isn’t only made up of serene sounds that symbolize ambient music. It also includes rather harsh, grating metallic noises and muddy soundsl. Spaces and nature don’t just possess nice, gentle elements. It also has a scariness to it. I actually think there are more scary factors than not. I want listeners to understand that aspect of it while listening, too.

– You’re saying that sounds of nature aren’t the superficial sounds you imagine them to be, like bird calls or flowing water. You think the disturbing sounds of the drone from Nostalghia is a more accurate depiction of nature?

Hirose: Precisely. That was intentional. The producer had asked me to include natural sounds. Since I was still in the trial-and-error stage while making Nova, I obliged. But Nostalghia is different. The first song, “Seasons,” puts an end to the Nova era, and takes the music to the next level. Looking back, it was a fear I had towards nature. For example, people often pray at shrines to make sense of natural disasters, to calm mother nature down. Perhaps I was trying to express that sentiment through sound.

On the category “Japambient”

– In the liner notes, Tastuhito Ito uses the term “Japambient.” How do you feel about terms like these?

Hirose: I think they’re interesting words. If there’s “Japanoise”, why not “Japambient”? It makes it easier to explain to a foreign crowd. No matter how much we try to explain that it’s spatial music, they might interpret it as ambient. People are quick to categorize things.

– I think there are a lot of foreign listeners who want Japanese elements in Japambient music. Do you think there are any commonalities between music of different Japambient and Japanese environmental musicians? For instance between your, Mr. Ashikawa’s, and Mr. Yoshimura’s music?

Hirose: There are similarities, like how we think about Japanese seasons. We’re heavily impacted by the changing humidity and atmosphere we experience here. When foreigners listen to that, they may interpret those elements as Japanese sensibilities. Even if we use Western instruments or Western music theory, the subtleties in the notes might have a Japaneseness to them. That being said, I didn’t make Nova or Nostalghia with the intention of incorporating Japanese components. But it’s possible that some Japanese elements were put there subconsciously.

Yutaka Hirose

Sound designer. Born in 1961 in Kofu City, Yamanashi Prefecture. Released album Nova as part of Misawa Home’s Sound Design Research Lab series “Soundscape” in 1986. In the same year, Hirose joined Sound Process Design, a company started by Satoshi Ashikawa, and worked on the sound design for projects in several cultural and commercial facilities. In 2019, Hirose re-issued Nova. Released by Swiss label We Release Whatever The Fuck We Want, the record included a bonus track with unreleased recordings and gained worldwide attention. In May of 2022, Hirose released Nostalghia, his first album in 36 years. Hirose plans to release Trace Sound Design Works 1986-1989 with the same label on July 1st.

Translation Mimiko Goldstein