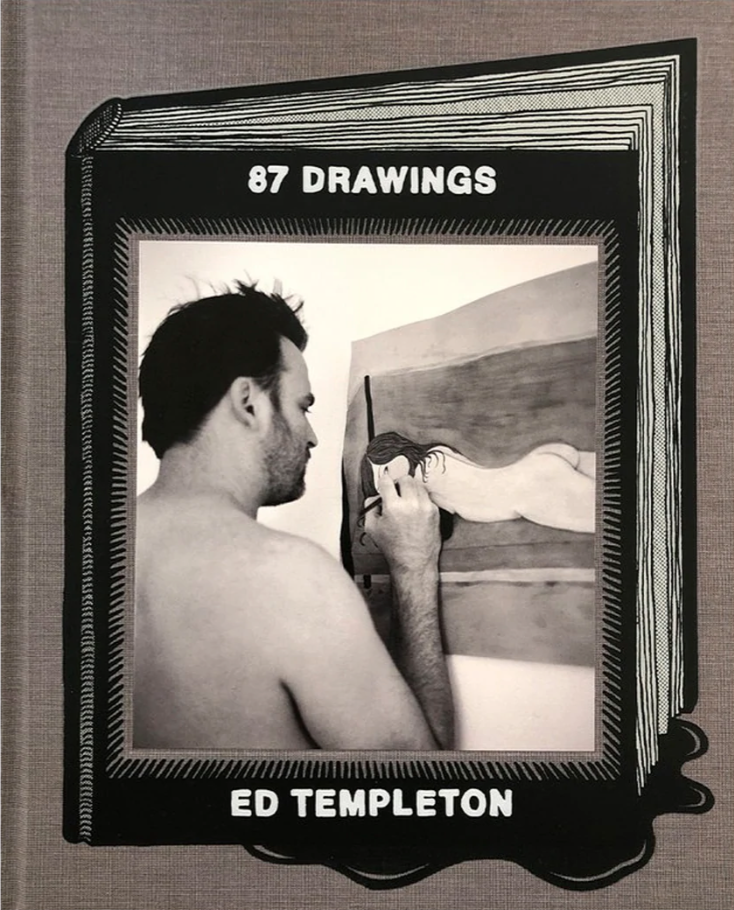

A special event was held at the Bookmarc Tokyo on May 6th to commemorate the release of Ed Templeton’s new book 87 Drawings. The book is a retrospective collection of the images that covers a span of over 30 years from 1990, and features personal drawings including several portraits of his wife and collaborator, Deanna Templeton; a self-portrait; and a drawing of them together. For the event, Ed talked to editor/writer Taku Takemura and photographer Taro Hirano via zoom from his home in Huntington Beach, California. Read on for the day’s conversation where they talked about the time when they first met and the creative process behind his new book.

“Loving Love and Hate”

I sometimes feel that Ed Templeton’s works of art resemble the spirit of skateboarders. He observes his hometown and tries to fit in or strays from the scenery. He laughs or gets angry on the street. He may be happy or suffering. Ed is the owner of Toy Machine Skateboards and a professional skateboarder that I admire, so maybe I tend to see his photographs and paintings in a favorable light? When I review his work again with this in mind, I always know that that is not the case, and what’s appealing about his work has never changed for me. Through the monitor, Ed and I meet for the first time in a long time. I wonder what he would tell me this time.

Taku Takemura: It’s been so long since I last saw you. Almost 10 years?

Ed Templeton: Yeah, it’s been a very long time.

Takemura: Do you still live in Huntington Beach?

Ed: Yes. It’s a really crazy place. During the pandemic, nobody here in Orange County cared about it. It’s a very conservative place, a republican place, so nobody wore a mask, nobody respected anybody else… It’s a very strange place.

Taro Hirano: But you’ve been living there for a long time, so you must love it there?

Ed: I love it and I hate it at the same time. Where I live is a big source of inspiration for my photographs and for my painting, probably because I like it and I dislike it at the same time. There is a lot of things that bother me about where I live, and it kind of fuels a lot of art work I make.

Hirano: Then what if you live in the city where there is nothing to hate about, you wouldn’t be inspired to create art?

Ed: Not necessarily. I don’t think you need to hate or both love and hate, but that’s just what it is for us. Because our families are here, we have deep roots here. Skateboarding also kept me here originally. So it’s just for us, it’s a love-hate relationship now. It’s a beautiful place, I’m not angry that I live here. We live by the coast and the weather is always amazing so I have a lot to be happy about. I think anywhere that I live would be the same because I like to look at, and in some ways, criticize but also celebrate people

“It’s a combination of something I made up completely but also using photographs as a reference”

Takemura: There may be some people here who are new to you, so can we start with some basic questions?

Ed: Yeah, of course.

Takemura: Last time I interviewed you, you said you were into ninjas before you got into skateboarding. How did the boy who wanted to become a ninja got into skateboarding?

Ed: [Laughs] I originally saw a few kids skating down the street and they ollied up the curve. And I couldn’t believe they could jump up the curve with a skateboard. So as soon as I saw that, I wanted to do that. That was when I was 11 or 12 years old, very late actually, for the skateboarders. Then when I started skateboarding, immediately I was welcomed into a group of people because I had a skateboard. Some kids I would normally be scared to hang out with, some punk rockers with mohawks, they said, “Hey, come hang out with us because you have a skateboard,” and they gave me a punk tape. And I started listening to punk music and started skateboarding. So I think everything that happened to me happened because I decided to skateboard one day. And then I fell into this crazy world, and here I am, 40 years later.

Takemura: What was the skate scene like when you first started skating?

Ed: It was kind of small. Huntington Beach and the Southern California was always a big skateboard and surfing kind of place. There were lots of surfers in my high school, but it also wasn’t popular. People would try to beat you up for being a skateboarder. So it wasn’t a cool thing to do. But it also was a good scene especially here, because the industry was based here. Vision Skateboards was in Costa Mesa right next town over. So there was a lot of people who were sponsored or a lot of pros lived here. Mark Gonzales lived in my hometown, so I would see him skating as a little boy. How amazing is that to be able to see Mark Gonzales, you know?

Takemura: I see. Now you are a skater, photographer and painter. Which did you start first, photography or painting?

Ed: For me, painting was first. I turned pro for skateboarding in 1990, and I started painting the same year. I had always been drawing as a kid, and after going to Europe for some skateboard contests, I came back very inspired to become a painter. And only four years later, I started doing photography.

Takemura: What inspired you to paint? Did you see someone’s paintings?

Ed: I had been looking at art books mostly. Where I live is not a very cultural place with lots of museums or art to go see. But luckily, my grandparents took me to some museums up in Los Angeles, so I did see some art. But mostly I was looking at books, and I was very inspired by a German painter named Egon Schiele. And when I came back from Europe, there was so much art in museums and in public there, it just made me want to become a painter. I was 18 years old. I was probably kind of naive and I just thought I want to paint. I thought it’s romantic and cool to be a painter, especially reading those books about Egon Schiele and different artists. So I started painting, I just did it.

Takemura: Let me ask you about your new book, 87 Drawings. I feel that a lot of your work is related to where you live, Huntington Beach, and I love how you capture both good parts and bad parts of the city without any preconceptions. Huntington Beach is a beautiful town with a lot of surfers and it also seems like a great place for businesses to market as well. How do you see the city you live in and the people living there? How do you get inspired?

Ed: I was shooting photos for years. I still do on the Huntington Beach Pier, and all around Huntington Beach and my area in general. In the early days, I was painting life where I would have someone sit and draw a portrait live. But over the years it’s changed, and a lot of my recent paintings has been based on my own photography essentially. I’d take multiple photographs and make sort of a composite using Photoshop sometimes to make multiple layers, and then, make a drawing of that. Photographs have been really helpful in forming the painting and making it look a little more realistic, and also, all the little details that come from a painting. So my new paintings have lots of trash on the ground, specific clothing that people are wearing, and style of plants and walls and architecture from Huntington Beach, Orange County are all have been wrapped in through my photography. So what’s happening is photography and painting are kind of starting to become together in a lot of ways.

Takemura: You certainly have many drawings with fine details.

Ed: Like this drawing in the book (#2), that’s something that came from driving in the car. Deanna was driving and this is an iPhone photo from the car, but then I go in and make new details. So the little bunny stuffed animal hanging from the thing was not there, trash wasn’t there… I change a lot of things and add more things. There is another one in here (#33)… The girl on the bike is not from a photograph, I just drew that. But then the man on the bench behind her and this man sleeping on the ground were both from separate photographs. And the architecture and the bench and the sign were from a photograph and I changed the sign. So that’s just the way to make all these different things. It’s like a combination of stuff I made up and references from photographs.

Takemura: That’s interesting.

Ed: It’s been fun learning over the years to add that because some of the drawings are so simple in a lot of ways, just a side profile or something that comes from memory. But I’ve been having a lot of fun with my paintings and some of my new drawings, incorporating all these different things. To me, it makes it more layered. I call it a hyperbolic reality. It’s like reality but you keep adding things and it becomes a heightened reality. There is a lot of truth but also a lot of statement, something that I’m putting into.

Hirano: If photographs are becoming your source material for your paintings, how do you distinguish photos for your photography and for drawings/paintings?

Ed: There is a lot of difference. A lot of the source material could come from iPhone photos even, which I don’t use in exhibitions or books for the most part. Although I did do an HB Pier photo show in Tokyo couple of years ago, which was cell phone photos, but that’s very rare. The photographs that are reference material, a lot of times are really bad photographs. One of my new paintings has a boy in a wagon. And the photo is so terrible but good enough to use it as a reference material. I could see the shape of the wagon and how the boy looked like and make a drawing based on this really bad photograph.

“We all are ridiculous things and we do stupid things, and it’s kind of interesting to illustrate those things. So I have to try to find the right mixture because I do love my fellow humans out there.”

Takemura: 87 Drawings is a collection of the images that cover a span of over 30 years from 1990 to 2021. What is the concept behind this collection?

Ed: I was talking with the publisher, Chris from Nazraeli Press. I told him that I’ve never made a book of my drawings before, and he was like, “Oh, we should maybe do something.” I wasn’t thinking about doing it, but when he invited me to do it, I started looking at some of my files because when I make a drawing, I’d scan it and save it on the computer. And when I started looking, I realized that there were hundreds of drawings to choose from. It was really fun to make an edit for the book and figure out what things should be used. There’s a small book by David Hockney called 72 Drawings by David Hockney and that was the inspiration for the title of the book. I didn’t know what number it was going to be, and we actually changed it at the last minute. It was supposed to be 85 Drawings, and then we realized we had 87 in there. So I had to go in and redo the title [laughs.]

Also, it’s funny because a lot of my photo books have artwork on the cover, and now my drawing book has a photo on the cover. Because David Hockney’s book has a shot of his studio [on the cover] I thought I should have a studio shot, and this was the coolest studio shot we had. Also, he has these numbers in the book at the top. That was also the inspiration for having the numbers at the top like that. It was just fun because David Hockney is a painter that I like a lot. It’s fun to just take inspiration from some book he did as a starting point for my book. It’s a very different book, but it was almost like having a conversation with an older painter. It’s like, because he did this, I’m going to do this, and that’s what everything is. That’s what skateboarding is. You see someone do a trick, and you’re like, “Oh, I want to do that but I’m going to do it a little different,” and you do something. And that’s how everything progresses, you know? I like the idea of having a conversation with someone I respect.

Hirano: I believe Nazraeli Press is famous for photo books? Could you tell us a bit about your publisher?

Ed: Yeah, he’s a famous publisher. He does Todd Hido books and Mark Steinmetz books, a lot of really great photography books and has been doing it for so long. But he’s also changed over the years, and he does so many other things besides books now. He has a farm and he’s making olive oil, and he’s doing books almost on the side it seems like. So it was kind of interesting he was inspired to publish the book of the drawings. But even though he’s known for photography, he has done some art books through the years, so it’s not super strange for him.

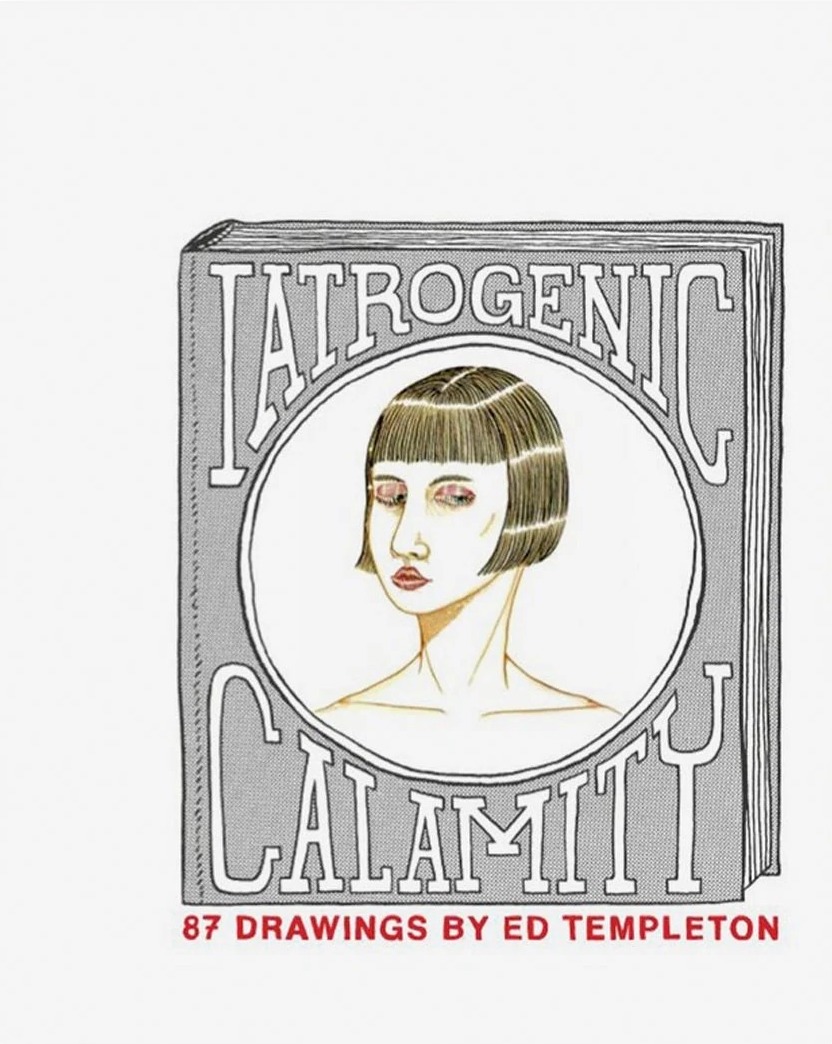

Takemura: It says “Iatrogenic Calamity” on the first page of your book. It looks like a subtitle of the book, but what does it mean?

Ed: Even Americans have a hard time with that one. Iatrogenic is a very strange word that nobody uses. You never hear it ever in any conversation. It means that the thing you are trying to do to help you also hurts you. So if you go to the hospital because you’re sick, but then you get even more sick at the hospital, that’s called an iatrogenic disease because you got it at the hospital. I like sometimes finding strange words to use for my books. I have one called “Tangentially Parenthetical” which nobody likes to say because it’s hard to say [laughs.] I probably make my books not sell very much because people don’t understand. But I just like having fun with the words. And that was like a fake cover of an imaginary book, if you will. It’s kind of funny because obviously, within the pandemic that just happened and there’s a lot of iatrogenic calamities happening.

Takemura: Also, is this your grandmother on the last page?

Ed: My grandmother, yes. She had just died and I was very fortunate to be in the room when she died. We were all holding her hand, so in a lot of ways, it was very sweet and peaceful death. But it’s also very strange because when someone dies, there’s a strange period after they die. Before the practical things happens, like people come to take the body, there is a moment where you’re sitting there in the house with your dead grandmother. I don’t think any of my family knew how to process that or how to act. But I thought, in the tradition of old paintings, a lot of times in the past when someone was dead, they would take a death mask. So in that tradition, I made a drawing of my grandmother. That’s why I used it in the book to dedicate the book to her, because she’s the one who showed me museums when I was young and I felt like she was the person who planted the seed to be an artist. There is a dedication here, it says, “This book is dedicated to Constance Templeton who is responsible for exposing me to art at a young age, causing a paradigm shift that has enriched my life immeasurably.” Paradigm shift is when your world changes, you suddenly see things in a different way. It’s like your worldview changes and that’s what my grandma did for me. She changed my world.

Takemura: This book also consists of several drawings of your wife, Deanna, and the portrait of you two. What does she mean to you?

Ed: She means a lot to me because over the years we have started working together more. We help each other with our projects. She just did a book this last year called What She Said published by Mack Books, and I did the layout for that with her and the design part of it. I also trust her opinion on my projects. She might question me about a photograph and make me think about it more, asking me “Why would you use this photograph?” It’s good to have that kind of person who you respect. And over the pandemic, it’s even more interesting because we don’t go outside anymore [laughs.] For a long time, we have not been going outside, and we started cooking together. We suddenly learned how to cook over the last two years, so that’s been really nice.

Hirano You mentioned that you love and hate Huntington Beach, and you like to criticize and celebrate the town and the people living there. I don’t think it’s easy to balance it out. it’s easy to criticize a crazy situation but not easy to accept it positively. But you do it so well, and I think that is your art, and that’s what I love about your art.

Ed: Thank you very much. Thomas Campbell, a friend of mine once told me that it’s really easy to make paintings about hate, but it’s really hard to make a joyful painting. So I agree with him, but I like to try to find a balance if I can, because I like to have some kind of criticisms. I think sometimes humans are ridiculous. We all are ridiculous things and we do ridiculous, stupid things, and it’s kind of interesting to illustrate those things. So I have to try to find the right mixture because I do love my fellow humans out there. It’s a celebration of how ridiculous we are, that’s really what it is [laughs.]

Takemura: I heard that Thomas Campbell grew up in Orange County but he hated, it so he moved to Santa Cruz. Is that true?

Ed: Yeah, it is true. He grew up in Dana Point which is south of where I am, and I think he also hated it. It’s a weird place for someone like Thomas or me. On the political spectrum in America, we are considered liberal or progressive or on the Democratic side, and where I live right now is very Republican and right wing. It’s like there are Trump flags everywhere, so it just feels kind of weird in some ways. That’s one of the parts I want to criticize when I’m doing work about this place.

You know, there’s a Japanese show called Old Enough that is now on Netflix, and everyone’s talking about it in America. We watch movies every night and some of the movies are more serious and depressing, so to clean our palette after depressing movie or a sad movie, we watch one of those Old Enoughs. It’s super cute and it reminds us of Japan and just how cute everybody is and the kids are so sweet [laughs.]

Taku: Well, thank you for sharing your stories about the new book today. It was very interesting.

Ed: I know it’s not allowed right now for us to just come over as a tourist, but I hope that we can come back soon, hopefully this year. Thank you so much for coming tonight!

Ed Templeton

Born in 1972 in Orange County, California and based in Huntington Beach, California. Ed Templeton is an artist, photographer and professional skateboarder who founded Toy Machine Skateboards. He was inducted into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame in 2016. Templeton has published numerous books and zines of photography and drawings. His work has been exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA), the International Center of Photography (ICP), and the Palais de Tokyo, among others. His work is included in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ghent, Belgium, the Orange County Museum of Art, and the Bonnefanten Museum.

Instagram:@ed.templeton

Taro Hirano

Born in 1973. After graduating from Musashino Art University, he started his career as a photographer in 2000. While based on skateboarding culture, he has contributed for culture and fashion magazines as well as advertisements. He ran No.12 Gallery from 2004 to 2019, and had curated exhibitions for various independent artists. His books include POOL, BARABARA, WORKSPACE IN TOKYO, Boku to Senpai, LOS ANGELES CAR CLUB, THE KINGS, and I HAVEN’T SEEN HIM.

Translation Nao Machida