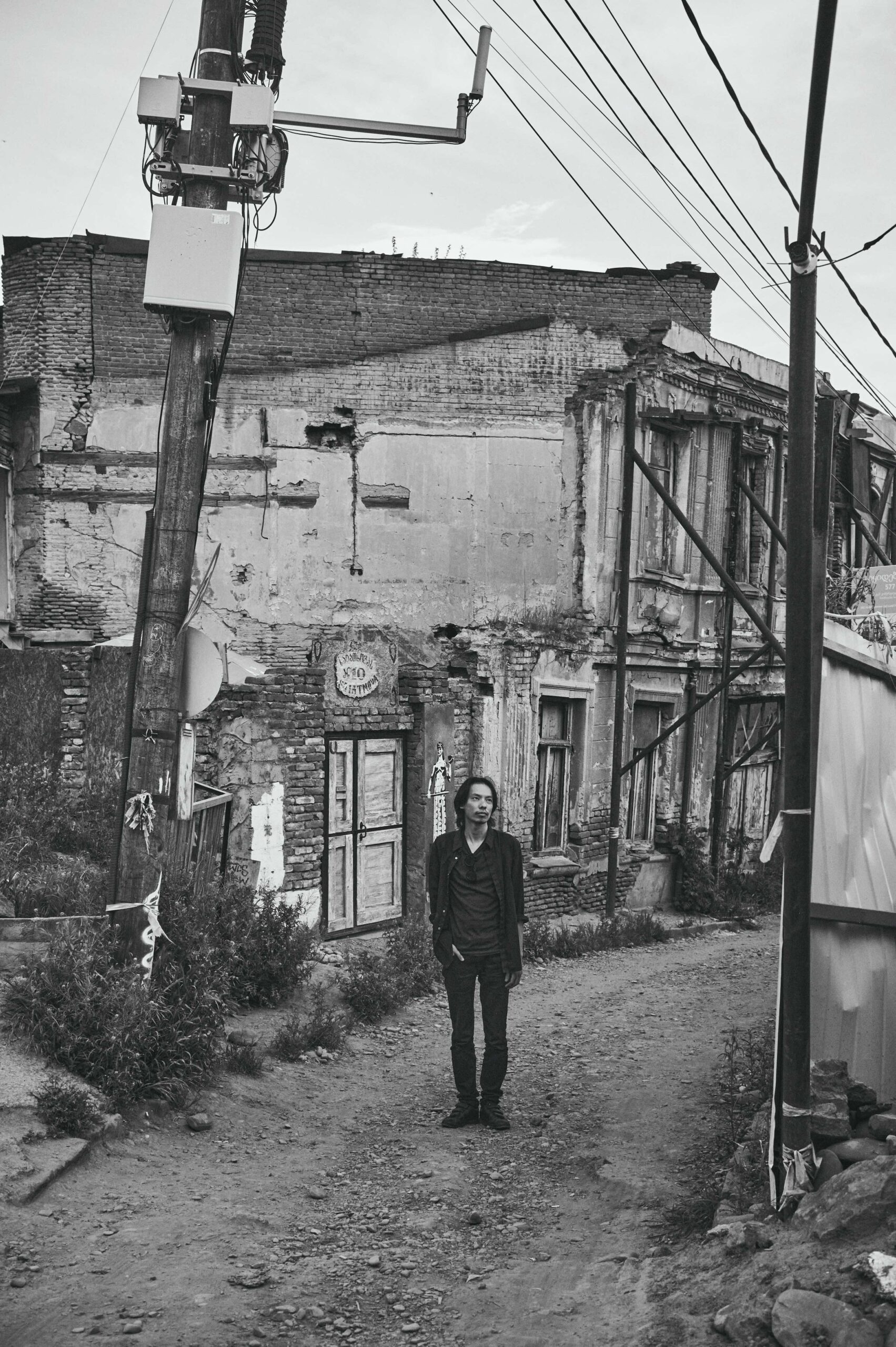

More than 30 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia has retained some of the Soviet era in its architecture. Its unique and exotic cityscape is a mixture of Eastern European and Western Asian cultures. The mixture of exposed red brick, modern architecture, brutalist buildings from the Soviet era, and crumbling housing complexes all coexist in the country’s architecture. At first glance, these seemingly contradictory elements create a strange sympathetic feeling that gives the city an exotic color.

One Japanese architectural designer was so fascinated by Georgia that he started his own business in its capital city of Tbilisi. He is currently working on a project to breathe new life into historical buildings that are falling into disrepair by leaving them as is and renovating them. The average monthly income of people in the city with futuristic landmarks designed by famous architects and seven-star luxury hotels, is equivalent to 30,000 to 40,000 yen. Where is Tbilisi headed in the midst of gentrification?

We interviewed Nao Tokuda, who moved from Kansai to Tokyo, Copenhagen, and then to Georgia, about where he continues to expand his activities. What is his goal in the country dubbed “the last unexplored country in Europe?”

The site of a former electric power company built in the Soviet era. Currently, only a few companies occupy the building as tenants. Rumors of its demolition continue to abound.

Leaving behind a small world to take on challenges in the unknown

–Denmark is famous for its design. But it’s quite unusual for someone to move from Copenhagen to Tbilisi, Georgia. What made you make the move?

Nao Tokuda: First of all, it all goes back to the reason why I left Japan. I grew up in downtown Kansai. There were no foreigners in my neighborhood and I had no exposure to foreign countries. My life started to take a turn when I moved to Tokyo and met my half-Japanese and returnee friends.

I experienced such culture shock there that it was as if Tokyo was my first time abroad. It was my first experience greeting people with hugs, which is a common custom nowadays (laughs). But it was there that I realized what a small world I had been living in! (laughs). That’s when I started thinking about living abroad.

At first, I thought about studying abroad, but a good friend advised me that since I already had a career as an architectural designer, I should make the most of it and get a job. That’s when I started researching architectural design firms around the world.

–Did you move to Copenhagen because you were offered a position at an architectural design firm?

Tokuda: Yes. I had always liked Scandinavian design, but I honestly would have been happy to work for any design firm that was interesting to me because I was confident in my work skills. But I was never a person who was open to foreign countries or to foreigners, and I had hardly even been abroad. Of course, my language skills were also limited, and I had never visited Copenhagen before. Getting an offer from a design firm there was the only opportunity I had to move to Denmark.

–Perhaps someone with no expectations is better able to dive into the unknown without being afraid.

Tokuda: I lived in Copenhagen for five years and worked at a local design office surrounded by locals. Just like I did in Tokyo, I was like a sponge and absorbed a lot. Denmark’s standards are high for everything. The environment and education are excellent and they also have good taste. I’m not kidding. It’s an environment where architects are everywhere.

–What made you transition from such a good environment to a developing nation like Georgia?

Tokuda: It’s easy to get around from Copenhagen, so I would often travel around Europe on weekends and holidays, and became interested in Eastern Europe. I was intrigued by the restrictive Soviet-era architecture, the unique atmosphere of the cities, the low cost of living, the people’s lifestyle, and all the other things you don’t find in the West. People in the East admire the West, because perhaps they want to join the EU. They also have insecurities regarding their positionality to the West. There’s a part of the East that is similar to my old self who wasn’t able to speak English well, wasn’t comfortable with foreigners, and wasn’t assertive.

I’ve been to Latvia, Ukraine, and many other Eastern European countries. But I felt that Georgia could provide the best environment for what I learned in Japan and Denmark. I’m also able to experiment and be creative in ways that are impossible in Japan or Denmark. To me, Tbilisi feels like a laboratory.

–How do you actually feel being here?

Tokuda: Coming from Denmark, where the cost of living is high and everything on average is high-end, to a poor country in the easternmost part of Europe, where the average monthly income is about 30,000 to 40,000 Japanese yen, the gap was shocking (laughs). But in Georgia, you don’t feel self-conscious, and it’s a very comfortable place to live. I think everything from the architecture and design to the local club, art, and fashion culture, is interesting.

However, it was very difficult to find work locally the first year or two after starting my business. I still work remotely on Danish jobs while making local connections. I’m still experimenting.

In front of the Japanese tearoom deep in the old city of Tbilisi, lies a place that feels like you’ve slipped back in time.

–Western Europe is very competitive, but the infrastructure and international environment makes it an easy place for us Japanese people to work. On the other hand, although Georgia has a thriving tourism industry, it’s difficult to see how open-minded they are towards immigrants, since it’s still a developing nation.

Tokuda: In my case, I was partially attracted to that environment. As far as I know, there are almost no foreign or Japanese architects or designers there, so there’s basically no competition. Besides, I wanted to try competing in an environment that differed from Western Europe, one that doesn’t have everything already in place.

–You have worked on many modern design projects, but this project to renovate an abandoned building into a teahouse seems to be the complete opposite approach. How did this come about?

Tokuda: The teahouse is located deep in the popular tourist area called Old Tbilisi. It’s a historic area where the streets of the 18th century are still intact. I liked the location because of its ruins, but I also wanted to incorporate a symbol of traditional Japanese culture into the area. We renovated the second floor of an abandoned building over 100 years old to turn into a teahouse, but on the first floor of the building is UZU, a community house run by Japanese people, which was originally a place to promote Japanese culture to Georgians.

–Did it happen because you got approval from owners who liked Japanese culture?

Tokuda: Not at all. First of all, Georigans don’t even know what a tearoom is, so I had to explain that concept to them. With help from a Georgian event organizer, we held workshops with local university architecture students and young architects to promote the project. I’m probably the only person who would come up with the idea of creating a Japanese teahouse in a local Georgian town (laughs). But we were cautious of which elements to respect and which new elements to incorporate into the new design. In the end, we decided to stay true to the original façade as much as possible.

–I was surprised by the stunning location. It was as if I had slipped back in time and time had stopped. Not only that, but the contrast between the exterior and the tearoom is also unique.

Tokuda: The building itself is tilted at a 5.8 degree angle due to years of deterioration, but we’ve done our best to respect the exterior of the building as is and kept it intact as much as possible.

The texture, which has a plaster-like appearance, is actually cement. Cement has a history of several thousand years in Georgia, so we commissioned a local craftsman for that. The tatami mats, which are essential for a tearoom, were imported from Japan, and a Georgian ceramic pot is placed in the center, on top of which a bonsai tree is displayed, to create an even more Japanese atmosphere.

–The way it looks with and without the bonsai tree is completely different. Where did you order the bonsai from?

Tokuda: You’re right. I also think the bonsai is an important part of the room. I purchased it from Bonsai.ge, a plant center in Tbilisi that carries bonsai trees inspired by Japanese bonsai.

I want to preserve brutalist architecture while transforming memories of a dark history into future possibilities.

–Do you plan to continue to work on projects that combine traditional Georgian and Japanese culture?

Tokuda: The teahouse project is complete, but we will continue to maintain and update it. We’d like to use this as a model case for various projects. One we are currently undertaking is a project to renovate a housing complex built in the Soviet era.

–Soviet-era architecture can be seen all over Tbilisi. It’s all very photogenic, isn’t it?

Tokua: They look cool to foreigners like us, but that’s because we see them through a filter. For locals, it’s a negative legacy that reminds them of the communist era, so they’re not particularly fond of them. Soviet-built apartments were built in large numbers because they were inexpensive and could be built in a short period of time. And because they used the same template, they all look the same. Urban development has been actively trying to get rid of these apartments that are relics of a bad era. It’s a shame that this has led to the creation of so many strange, unnaturally-colored buildings, like a theme park with no coherent theme.

–It’s not only photogenic, but also a heritage, a culture, and a design that should be preserved.

Tokuda: Precisely. They’re doing things that are totally unsustainable which is causing thc city to revert back in time. I think we shouldn’t look at this architecture as a “negative legacy,” but rather renovate it in a cool way and reuse it. I’m working with young local architects on a project to achieve this.

Project updates and other information is available on the official website or on Instagram.

Nao Tokuda

Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1983. Moved to Tokyo after graduating from Osaka University of Arts. After working for about ten years as an interior designer for commercial spaces at a design and construction company and a design office in Tokyo, Tokuda moved to Denmark. He worked for a design firm in Copenhagen for five years designing interiors for various spaces, both large and small, including boutiques, cafes, and hotels. In 2020, Tokuda moved to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, and established Design Studio NAO. He has received several international awards for his work on various projects and continues to work mainly in Japan and Europe.

「Design Studio NAO. LLC」

Instagram:@designstudionao

Photography Kazuma Takigawa

Translation Mimiko Goldstein