In the Netherlands, where I live, life has returned to its former routine since the third vaccination was administered earlier this year. The Dutch value their freedom more than anyone else and has no fear of being seen. It is no exaggeration to say that masks have been a criticism, or even a taboo, for them since the peak of the corona epidemic, when it was mandatory to wear them. It is now almost impossible to see any local people wearing masks. The number of infected people is no longer reported in the daily news. These values and policies, which are the complete opposite of those in Japan, provide an interesting glimpse into a different kind of democracy.

Still unable to let go of my Japanese patience, I continued to live a life of self-restraint until this spring, but this summer I couldn’t stand still and began to fly out of Amsterdam.

Dutch photographer once recognised by Mapplethorpe but now forgotten

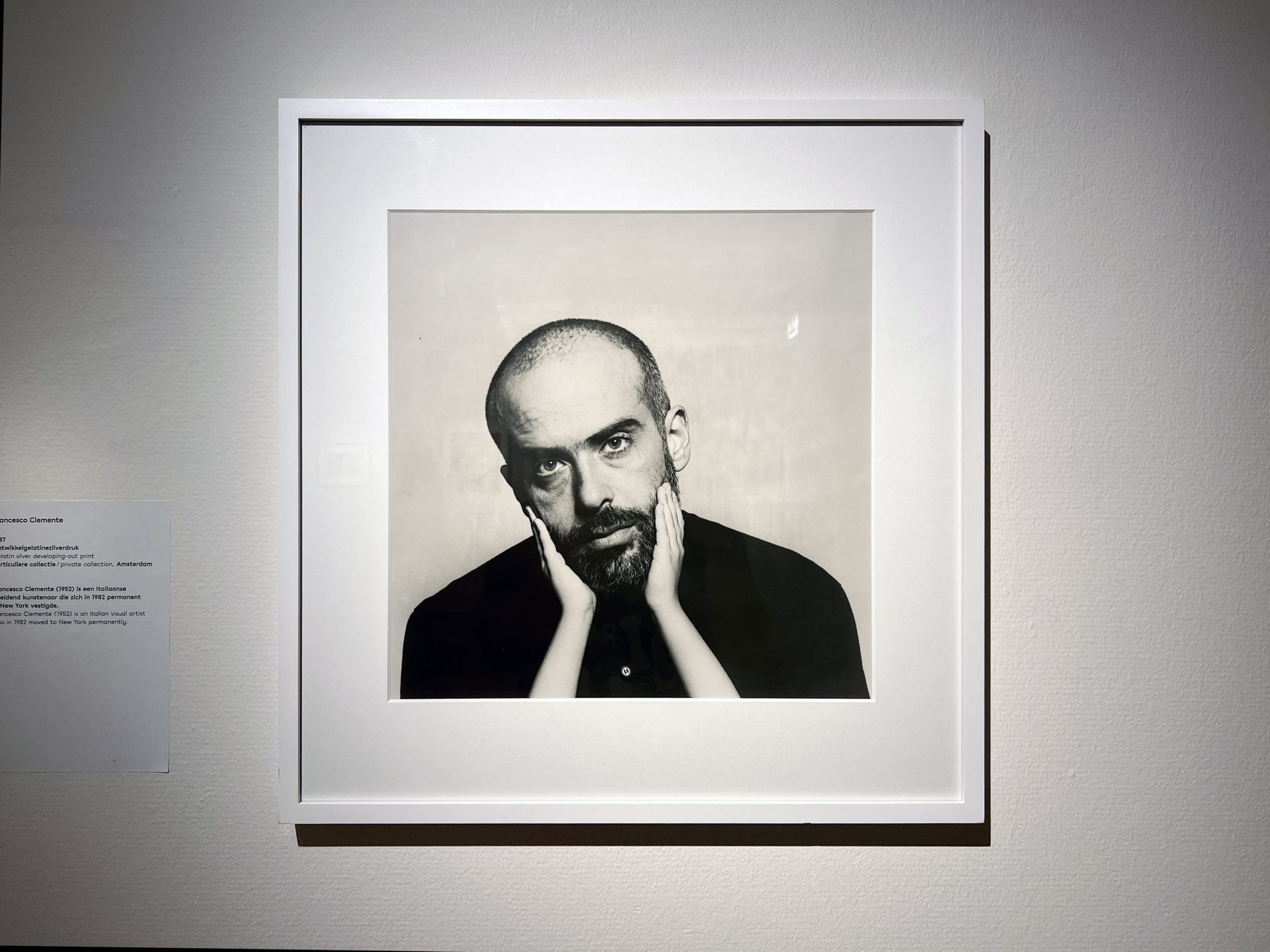

The first stop was to visit Den Haag, the administrative center of the Netherlands, for a photo exhibition by Dutch photographer Paul Blanca (1958-2021), currently on show at the Fotomuseum Den Haag. The exhibition is a substantial memorial to his death last year and consists of his most intense early work.

Blanca’s life has been a bizarre and spectacular one: in the 1980s, he made a name for himself as an art world hope with the audacity and subtlety that made Robert Mapplethorpe say ‘Paul Blanca is my only competitor’, but he gradually became addicted to drugs and alcohol.

Then, in 1995, a decisive event occurred. At the time, he was accused of being responsible for a bomb attack in Amsterdam. Despite the fact that there was no evidence and Blanca had an alibi, this incident led to his expulsion from the art world. His efforts were unsuccessful and he died at the age of 62.

Photograph extreme action

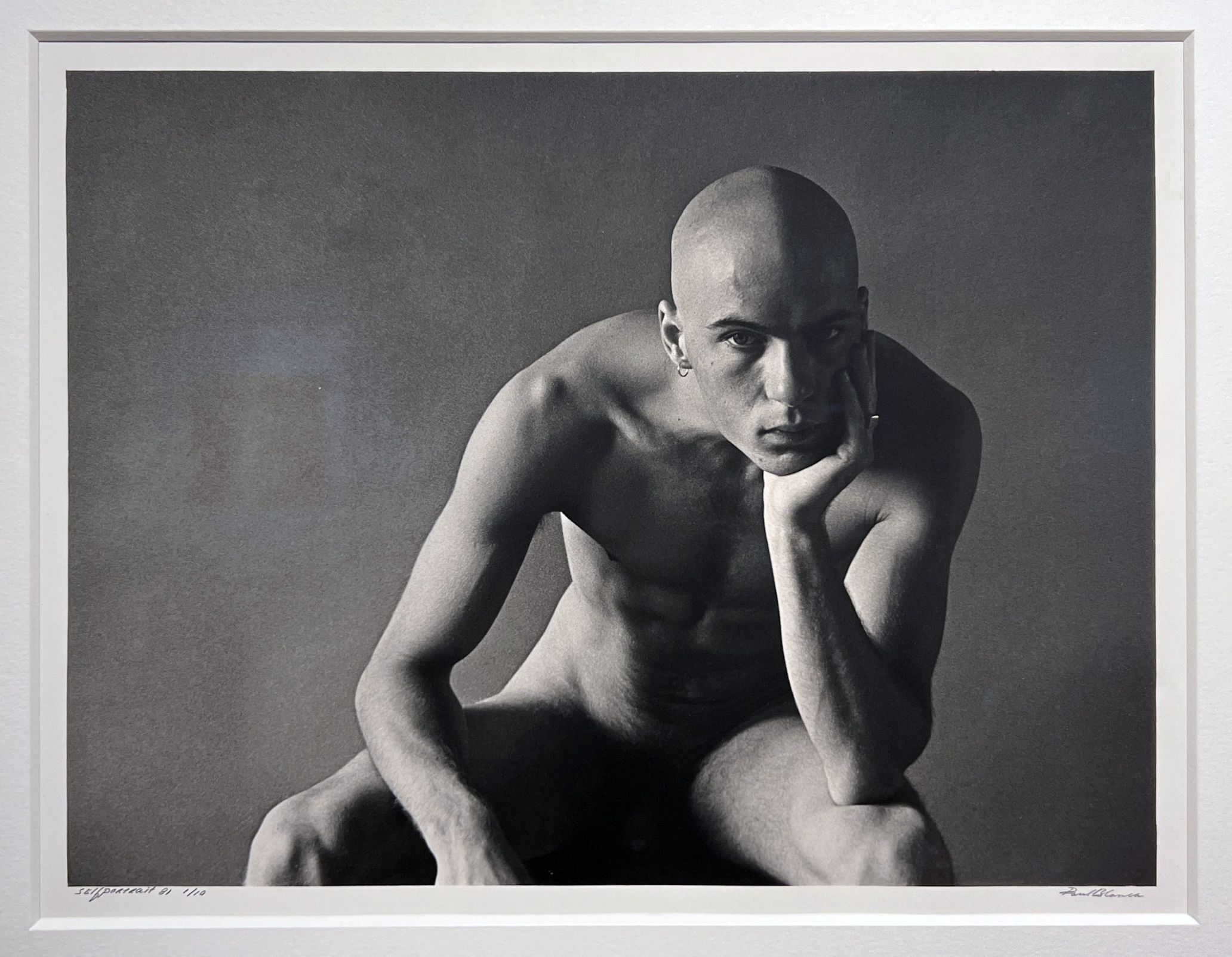

On display in the exhibition’s second room are a series of Blanca’s self-portraits from the 1980s, which can be regarded as his masterpieces. He performed uncompromisingly extreme actions in front of the camera, such as holding a live rat or several eels in his mouth, or piercing his cheek with an arrow.

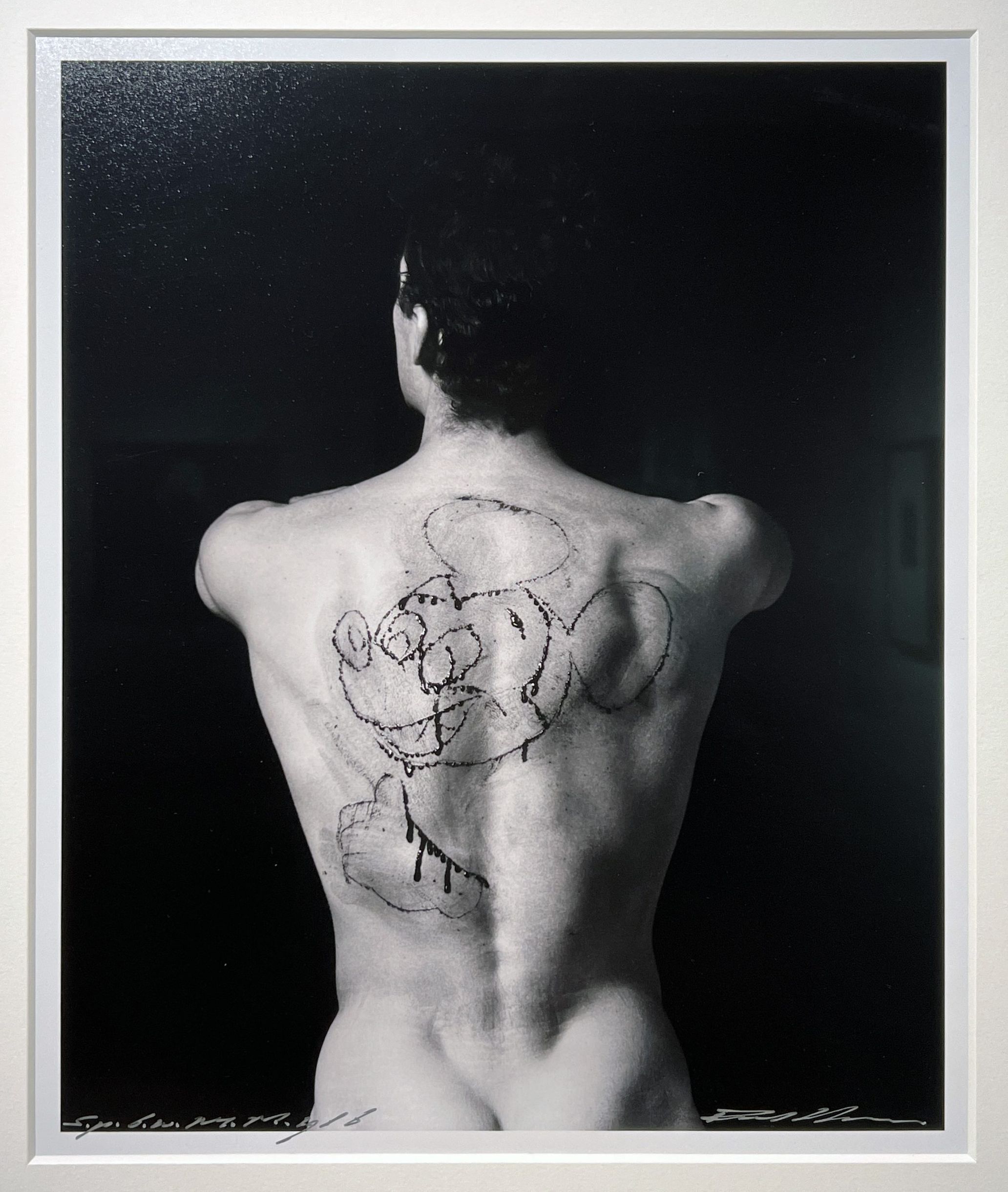

Photography is the best way to document the momentary display of restraint and concentration that comes from pushing the body to the brink. One of his most famous portraits is a shot of his own back, carved with a razor blade in the shape of ‘Mickey Mouse crying with his thumb up’.

Blanca’s violent and painful self-portraits are reminiscent of the body art of performance artists Marina Abramovic and Chris Burden, who in the early years of their careers attempted to push the limits of the body by making themselves into objects. At the same time, the fact that the painful scene succeeds in being aesthetically pleasing indicates that it is an expression in the context of Dutch portrait, which has continued since the time of Rembrandt and Vermeer. In Part 5 of my essays, I mentioned the Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf’s hybrid perspective of tradition and modernity, and the same can be said of Blanca.

Olaf and Blanca are from the same generation, but that is not the only thing they shared. Both had the Dutch master Hans van Manen as a mentor, and both had long careers as photographers who made portraits of their times. However, in contrast to the former’s rise to become one of the Netherlands’ leading photographers, the latter is now fading into obscurity after his death, which has been regarded as a taboo subject.

The strange life of Blanca

Here, let’s have a quick look back at his life. Blanca was born as Paul Vlaswinkel in 1958. Whenever he made a mistake, his stepfather would correct it with violence. To overcome this environment, he began kickboxing, which gave him a strong body, and he was discovered by the world-renowned choreographer and photographer Hans van Manen. As well as performing in ballets directed by Manen, Blanca also learnt photographic techniques and how to work with models from Manen, which led him to get into serious staged photography.

In 1979, Blanca had a chance encounter with Robert Mapplethorpe, who came to the Netherlands for a solo exhibition at a gallery in Amsterdam. Blanca then followed Mapplethorpe to the USA. In the 1980s, Blanca made a name for himself with a self-portrait series, but didn’t bring him the perfect breakthrough. Gradually, he began to turn to heroin and cocaine.

At the end of 1994, an attempted murder took place in Amsterdam. The car in which Dutch contemporary artist Rob Scholte and his then-wife were riding exploded. Scholte lost both his legs and his wife lost her foetus. Someone had planted a bomb under their car. Immediately after the incident, the Netherlands was in an uproar as a mysterious case with no known perpetrator or motive, but the following year Scholte announced three artists close to him as potential perpetrators. One of them was Blanca.

What the unsolved case has brought him

In the end, the police did not conclude that the three were the perpetrators and finally closed the case file without catching the real culprits. In an interview in 2010, Blanca said that Scholte at the time had links with criminal organisations and that he may have been victimised as a fallout from the trouble he had caused with them. In order to hide the truth, Scholte made Blanca the scapegoat because Blanca spent the most miserable life around Scholte. Despite this, Blanca’s galleries he belonged to expelled him and museums and collectors stopped buying his work. This was because, at the time, Blanca was in a situation where he could be suspected.

Although Blanca had consistently denied involvement since the time of the incident, he was in police trouble just four weeks after the attempted assassination of the Scholte couple. He was arrested for practising how easy it was to obtain illegal gas guns and hand grenades for a weekly magazine to which he was contributing at the time. Needless to say, people easily connected the hand grenade he was carrying with the bomb that attacked Scholte. Everyone in the city was convinced that Blanca was the culprit. Branded unilaterally as a ‘dangerous man with a weapon’, he was forced to live under siege. Blanca became increasingly dependent on drugs and fell into a negative spiral.

A quarter of a century after the incident, the prevailing theory is that they were not targeted in the first place, but a neighbourhood lawyer who owned a car very similar to the one the pair were driving on the day of the incident. However, the truth remains in the dark. It is unfortunate that, since this incident made Blanca’s life as an artist a misery, he is often mentioned only in connection with this bizarre incident, rather than his work.

Only in darkness does light shine

Despite his talent for producing sometimes brilliant masterpieces, Paul Branca has been shrouded in taboo for more than a quarter of a century.

The means of finding out about him are surprisingly limited, given that he has been treated as an invisible entity for more than a quarter of a century. The only published collection of his work to date is the catalogue of an exhibition held in Germany in 1993. The only other means by which we can learn about his activities and career is by following the Dutch-language articles that have been reported in the local media.

Nevertheless, I was drawn to Blanca, perhaps because of the deep darkness I saw in his life, overlaid with a Japanese photographer. Masahisa Fukase had an accident in the early 1990s when he was at the height of his powers as an artist, and spent the next two decades battling illness. His works lay dormant for a long time like a sleeping dragon and were rarely shown to the public until his death.

Only in darkness does light shines. The deeper the darkness, the brighter the photographer and his photographs. The two men died without saying much, but their works have not lost their appeal and will probably continue their wordless dialogue with the public.Now is the time to remove the ‘mask’ that has covered Blanca’s photographs for a quarter of a century and listen to his stories.

This autumn, a documentary recording Blanca in his later years, “Paul Blanca, This Film Will Save Your Life” directed by Ramón Gieling will be released. Although Blanca sadly did not get to see it completed, one can only hope that, as the title suggests, it will be the catalyst for a reappraisal and further study of his work.

■Paul Blanca, HOMMAGE AAN PAUL BLANCA

Exhibition Period: April 30th to August 14th, 2022

Location: Fotomuseum Den Haag (the Netherlands)