Tatsuki Fujimoto is a manga artist who is primarily characterized by his indifferent eyes on the subject matter that drives his stories.

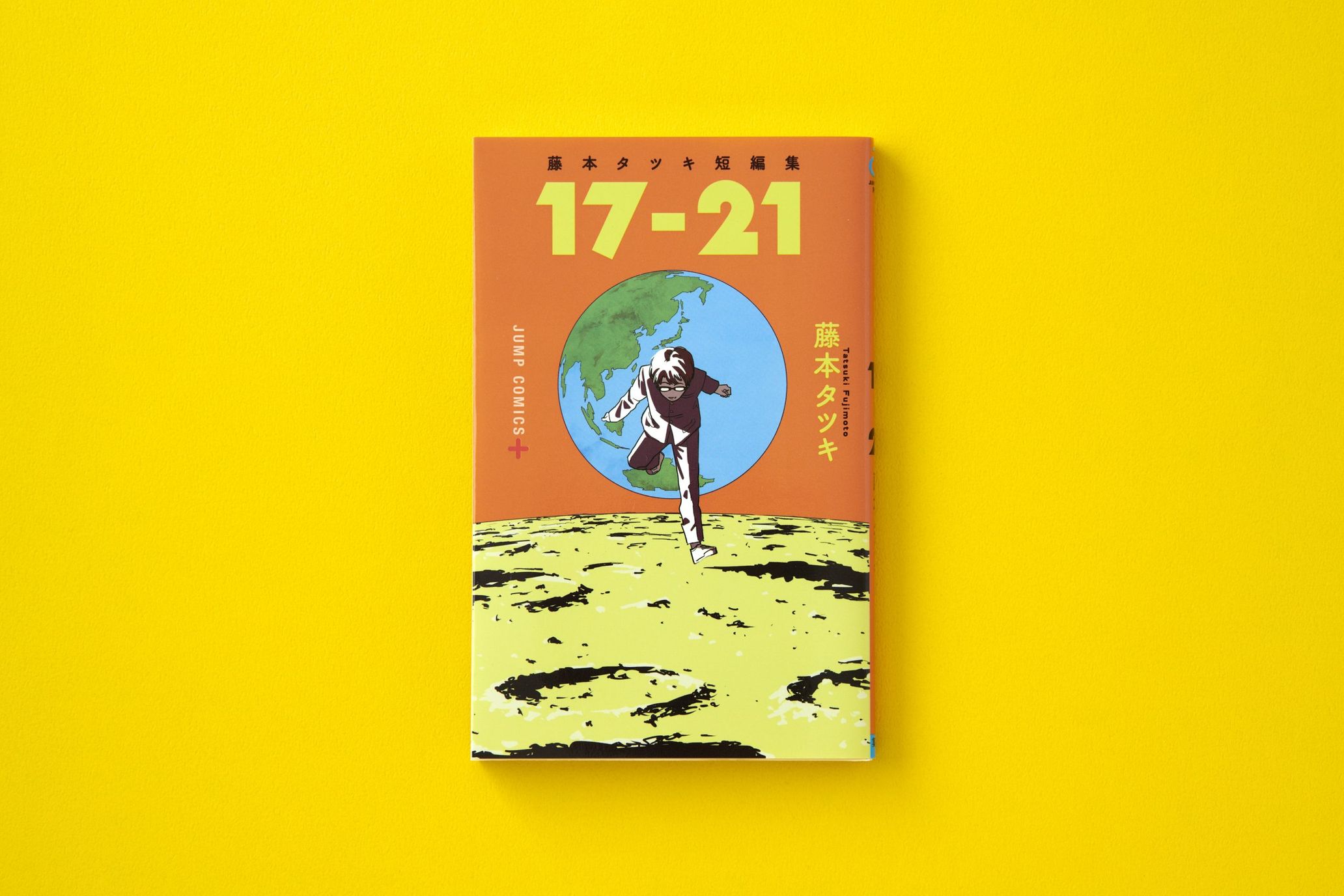

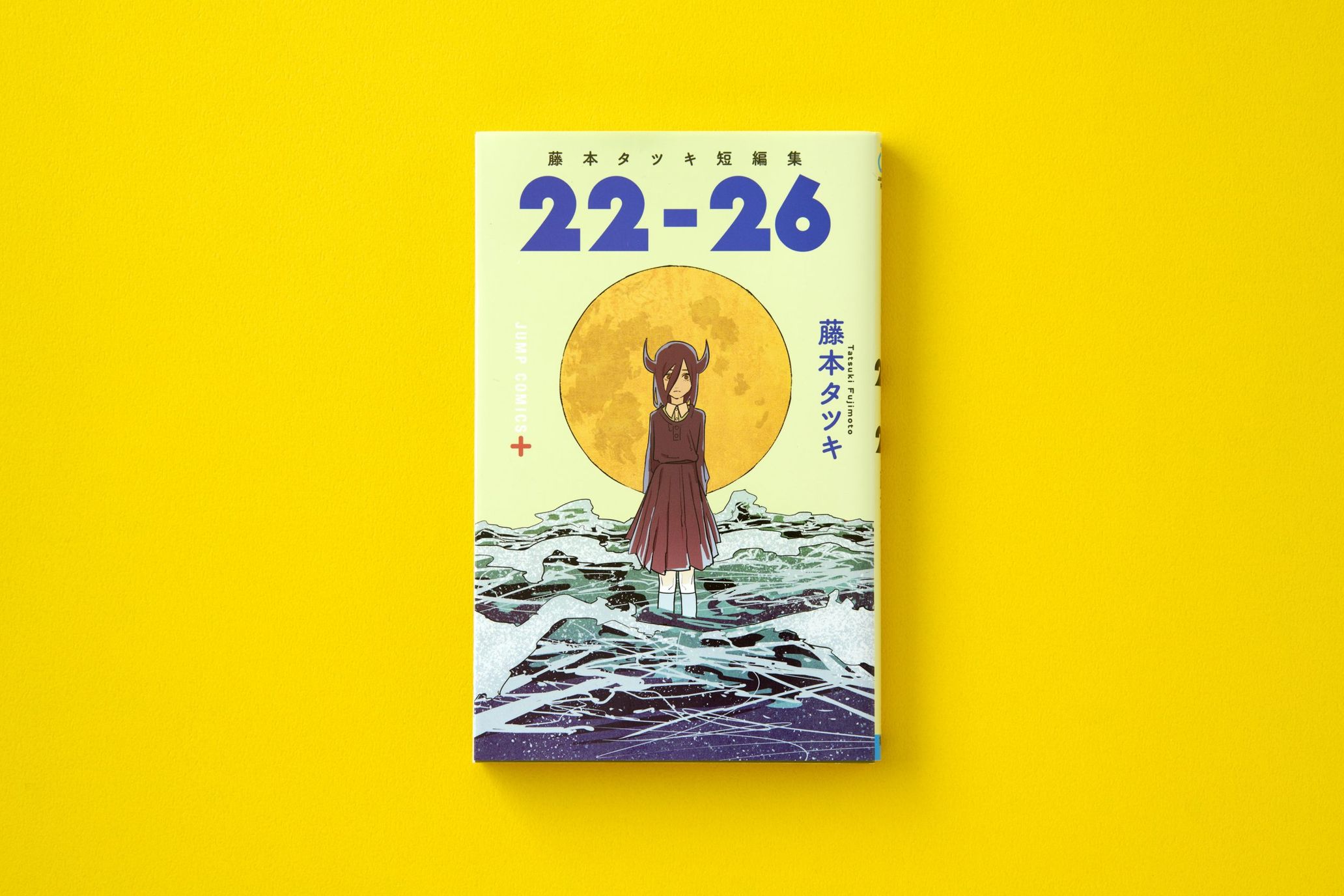

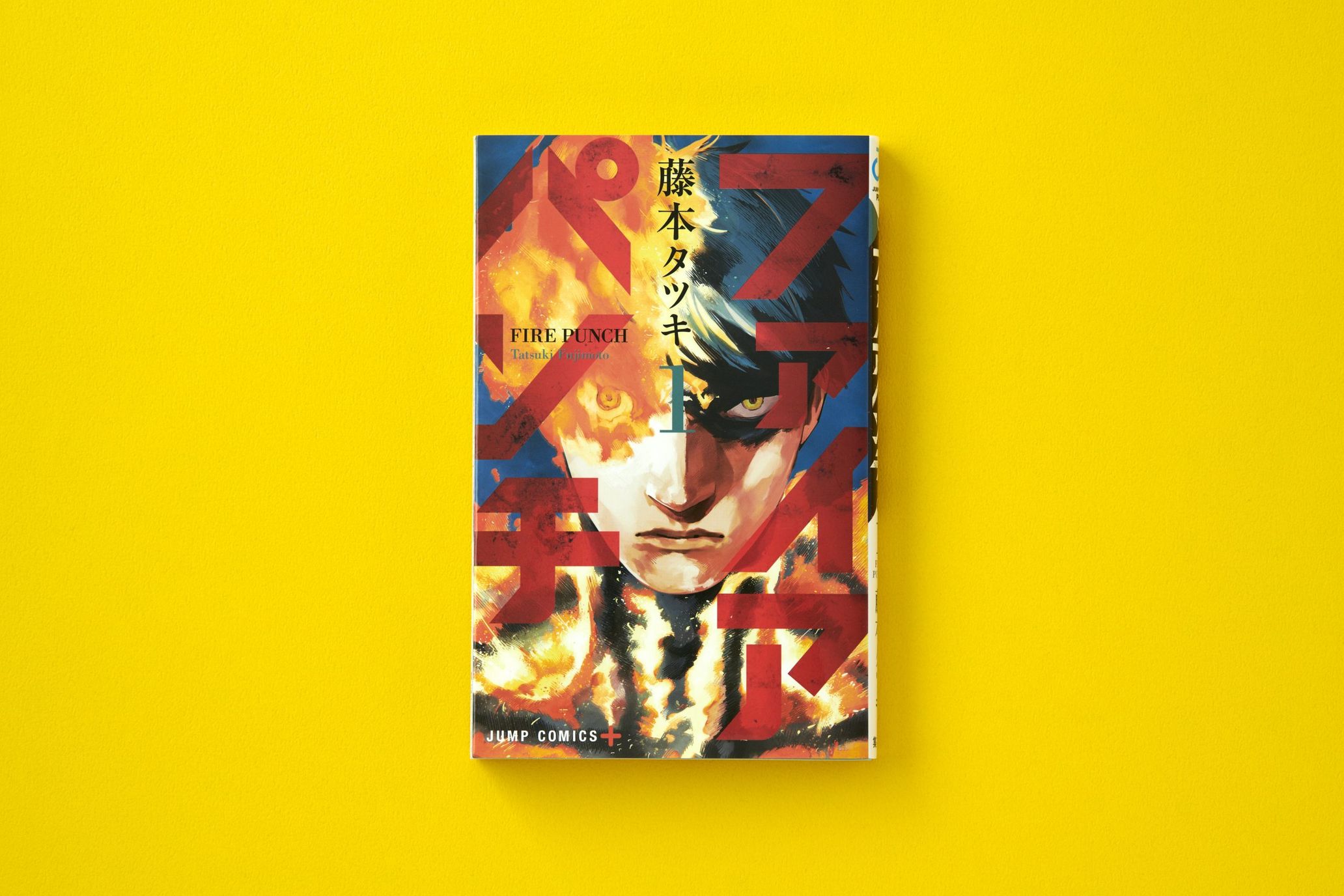

When one takes a look at his career as a manga artist, one would notice that, despite the spectacular success of Fire Punch and Chainsaw Man, he has spent much of his career as a “one-shot manga” artist. Fujimoto’s career as a manga artist began with his first award-winning work, Niwa ni wa Niwa Niwatori ga ita (庭には二羽ニワトリがいた, “There Were Two Chickens in the Garden”) (2011), which means that until 2016, when the first episode of his first full-length work, Fire Punch, appeared on the Jump+ web magazine, Fujimoto Tatsuki had spent roughly seven years working on short manga. The pace of his work was so extraordinary that he sent one story to his editor every day, and used the prize money from his one-shots to cover his living expenses when he was out of work for a while after graduating from university.

These facts and anecdotes demonstrate Fujimoto’s precociousness as a full-length manga artist and at the same time clearly show his lack of attachment to the subject matter of his stories. Even taking into consideration the fact that in the realm of shōnen manga, a “one-shot” manga is basically a stepping stone to forthcoming serialized manga in a magazine, it is clear that Fujimoto is not afraid to generate one pattern after another without regard to the subject matter of his own stories. Rather, it seems as if he sees a story as an interchangeable tool for developing his storytelling skills and achieving great success as a manga artist.

This kind of his artistic quality is demonstrated in a paranoid sort of way in his first full-length work, Fire Punch, in which the protagonist is an avenger, a hero, a god, and nobody at the same time, changing his name and even his identity from time to time. Such interchangeability is also evident with regard to the multiple female characters surrounding the protagonist, and the overall structure of the story is barely stabilized by the half-forcible maintenance of their one man-one woman relationships that the protagonist and female characters have. This bizarre fluidity in the narrative, which has been described as a “plot twist,” is precisely what reveals Tatsuki Fujimoto’s indifference to the subject matter in the story.

At the same time, it is important to note that the fluidity of the narrative in Fire Punch is optimized for the so-called “buzz marketing strategy,” which increases the number of views by inducing communication on SNS. Considering that the serialization of Fire Punch started as part of the “New Serialization Spring Campaign” of JUMP+, it is clear that the extreme nature of the story, with each episode taking a completely different turn, was accepted as a novelty mainly on SNS, and contributed greatly to the increase in JUMP+ site accesses.

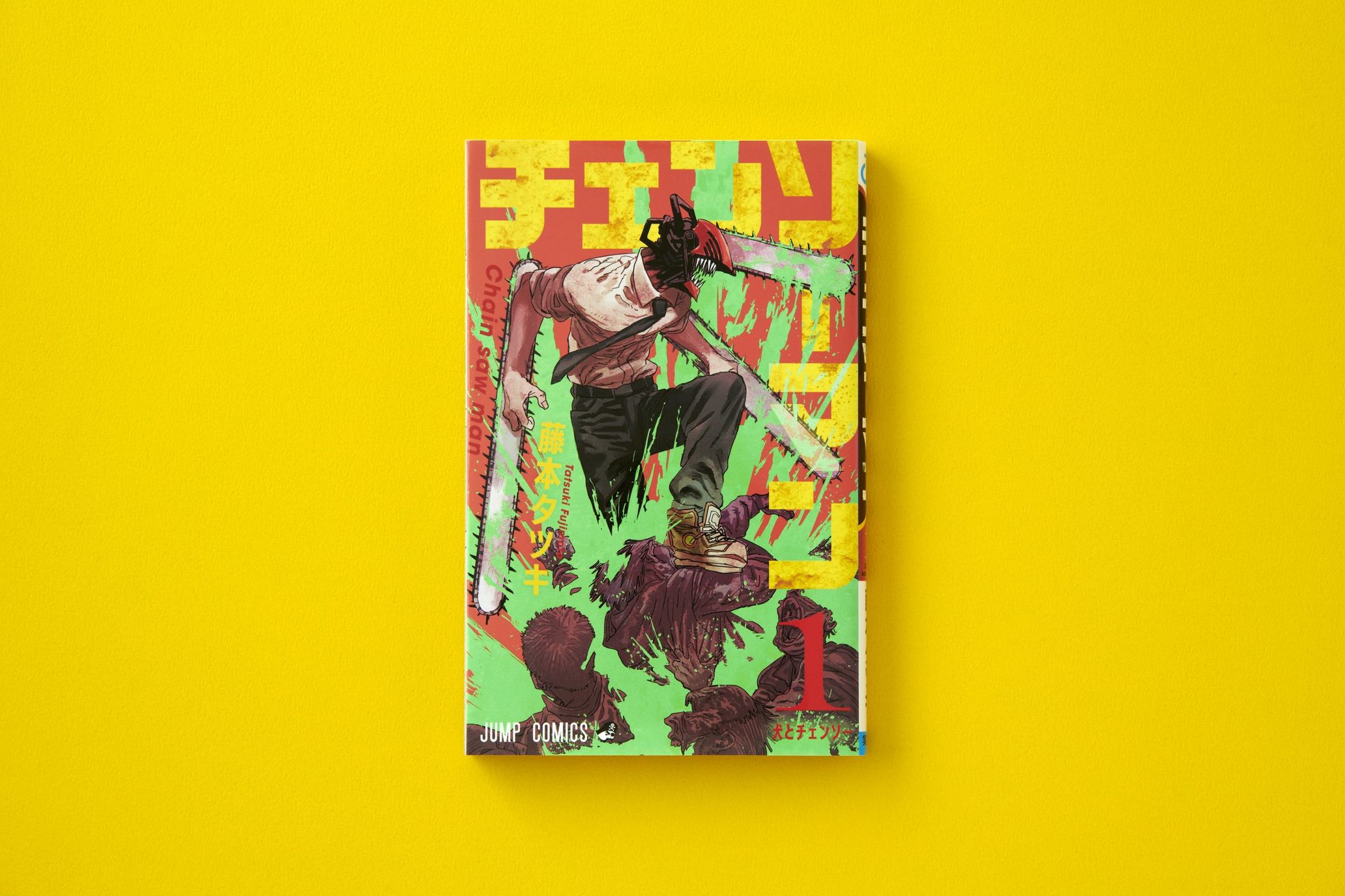

The situation surrounding Fire Punch can be summarized as a collusion between Fujimoto’s indifferent attitude toward the subject matter of the story and the SNS-centered consumer environment, but what is more suggestive is that the reader’s desires seem to have intervened in the story itself. The peculiar style of manga production, in which an interchangeable and open-ended story is brought together into a single form through the reader’s desire, is very important when considering the manga artist Tatsuki Fujimoto. This second characteristic was manifested in his next full-length manga work, Chainsaw Man. I will unfold it step by step.

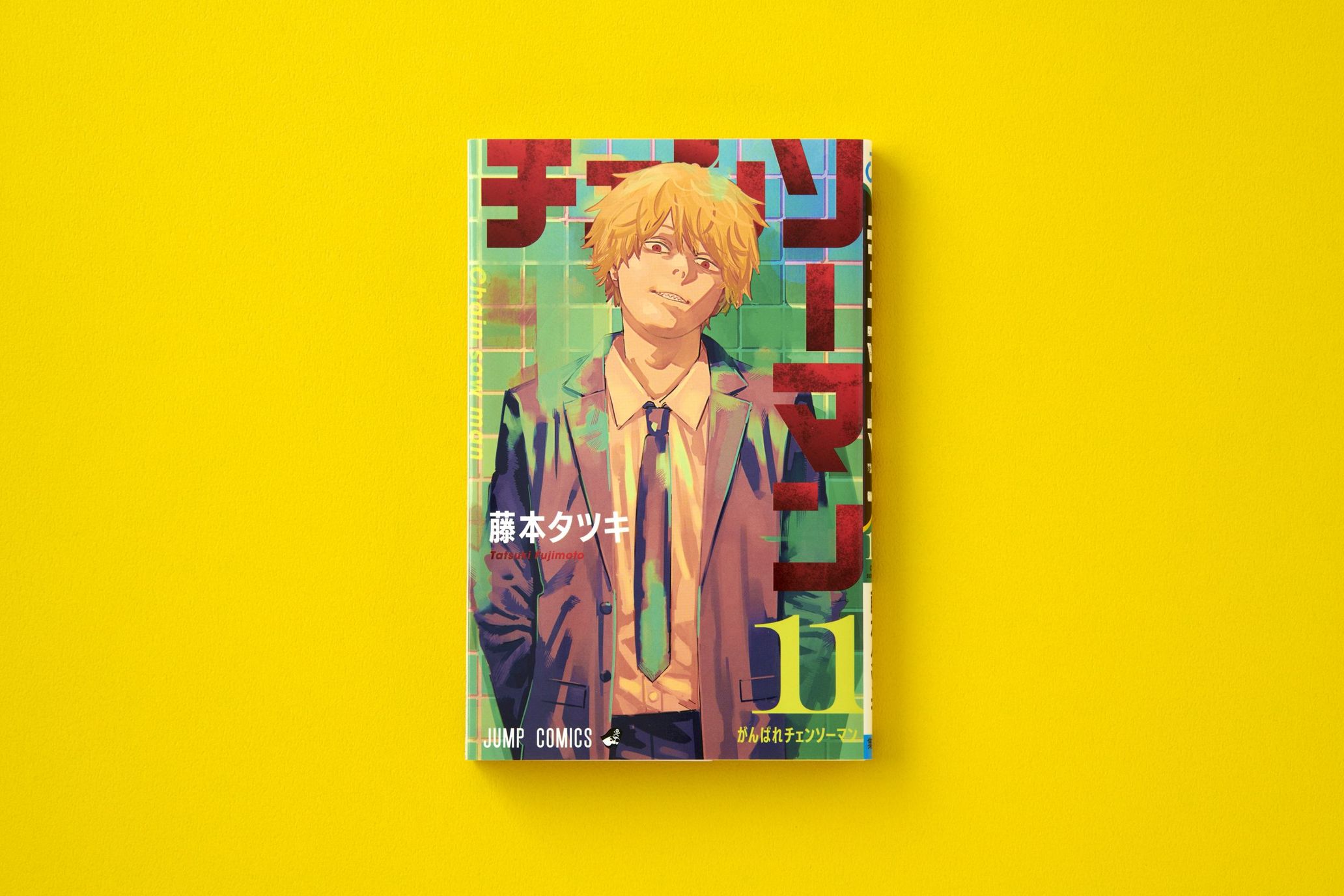

The Complicated Narrative Structure Behind Chainsaw Man

Denji, the protagonist of Chainsaw Man, is an orphan who is underage and has no job or education at the time the story began . He is a devil hunter who hunts the monstrous demons that infest the world in the story, and is exploited by the yakuza. He is living in extreme poverty, even selling his own organs and one eye to help pay his debts. He is a demon exterminator who seeks a “normal life,” but at the same time he is somewhat satisfied with his days with his partner, Pochita, a demon. However, his small happiness does not last long. Denji is cut into pieces by a Yakuza traitors, and he dies. However, his partner, Pochita, replaces his heart and Denji is reborn as a half-human, half-demon, saw-headed, deformed being. After Denji, who has fused with Pochita, kills the yakuza who betrayed him, a woman named Makima, who claims to be a devil hunter for the Public Security Bureau, comes to the scene. That is how the first episode goes.

The next several volumes depict how Denji, who works as a devil hunter under Makima’s command, interacts with Aki Hayakawa, a public safety devil hunter, and Power, a demon who has taken over a human corpse, and gradually develops a pseudo-family-like relationship.

It is important to note that the “normal life,” a situation where he would not have to worry about food, clothing, or shelter as long as he did the work he was given, that he consistently seeks and temporarily obtains is a wish that is driven by Denji’s origins of extreme poverty, and is by no means an intrinsic wish. This is tragically revealed in episode 82. In this episode, Makina confesses that she dared Denji to establish a pseudo-familial relationship with Aki Hayakawa and Power, and then had him destroy it irrevocably by his own hand, in order to mentally break down Denji, who was poor but self-sufficient, and force him to give up the “normal life” he was seeking. The episode, in which Denji becomes mentally incapacitated after it is revealed that the “normal life” he was seeking for was nothing more than bait to draw Denji into her plot, is one of the turning points in Chainsaw Man. What is revealed here is that his success as a devil hunter and the motives behind it were all planned and fictitious by someone else. Needless to say, the author of Chainsaw Man Tatsuki Fujimoto’s indifference to the subject of the story, which was discussed above, is linked to the absence of a basis for the motive of Denji, the protagonist of Chainsaw Man.

Nontheless, what complicates The Chainsaw Man is that the author who plays with the story and Makima who plays with the motive somewhat overlap, while the storyline that follows seems to criticize such a way of being. Specifically, it is Denji’s interaction with Aki Hayakawa and Power, which was only a stage set to hunt down Denji, that becomes the driving force behind his resurrection and revenge against Makima. In other words, by depicting how the accumulation of micro-relationships outfoxes the plot depicted by the antagonist, it suggests to the reader the allegorical theme of the antagonist being rebelled against by the subject who was supposed to be merely a replaceable pawn.

However, as a matter of course, the plot in which such an uncertain element in the work becomes the decisive factor in the storyline is merely something that has been skillfully designed by Tatsuki Fujimoto. What we have here are three layers of subjectivity: the subjectivity of Denji before episode 81, the subjectivity of Makima who controlled it behind the scenes, and the subjectivity of the author who designs the storyline, including the miscalculation of Makima’s plan. In the story of Chainsaw Man, the protagonist’s subjectivity is first denied, followed by the denial of the antagonist’s subjectivity. But it should be noted that by the avoidance of identification of the author and the characters, the existence of Fujimoto, the subject of the story’s designer, is brought into the background. In other words, the story of Chainsaw Man is within the author’s control, and it is not a thorough criticism of the author’s failure to recognize the inherent value of the subject matter, be it the protagonist’s motivation or the development of the story, and toying with them as he pleases.

Why, then, did Tatsuki Fujimoto present such a complex narrative structure that could be called an act of false self-criticism? The answer is simple: to deceive readers. Even taking into account the fact that the series of Fire Punch on JUMP+ was followed by the serialization of Chainsaw Man on Weekly Shonen Jump after its favorable reception, the difference in readership between JUMP+ and Weekly Shonen Jump is obvious and Chainsaw Man was subjected to more severe scrutiny with the possibility of discontinuation of the series in consideration. The extremely tricky plot-twist technique embraced in Fire Punch could not be used because of the readership of Weekly Shonen Jump above all, So I believe he had to be conscious of the formula of expressing some theme through story manga. In the process, he may have created the narrative structure of Chainsaw Man.

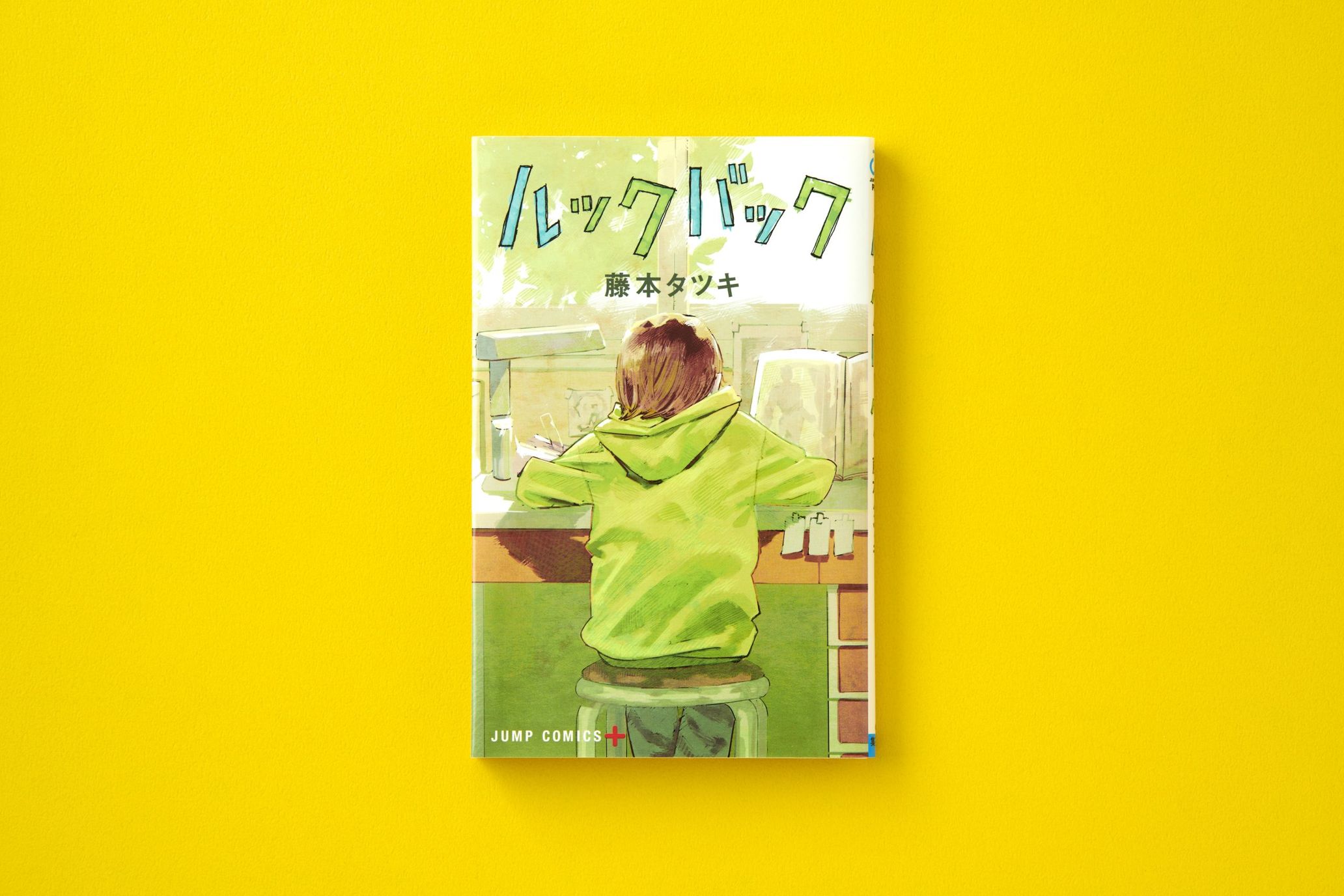

Tatsuki Fujimoto’s recent strange style, formed through the collusion of the absence of a subject matter and the reader’s gaze, does not, however, seem to be adopted in the one-shot manga form, which is created solely by the artist’s hand. While both Look Back and Goodbye, Eri are technically sophisticated, the subject matter they deal with is quite general: the former deals with the acceptance of the sudden death of a close friend, and the latter with overcoming middle-age crisis by bringing an end to adolescent memories. There is no unique and remarkable twists like in Fire Punch, which abandoned the theme in advance, or The Chainsaw Man, which deals with a self-critical theme. In this sense, Tatsuki Fujimoto certainly needs readers.

The second part of The Chainsaw Man has just started in JUMP+ magazine on July 13 of this year. With his reputation as a manga artist, his position in the media in which he is published, and above all, the way readers look at him, all of which are different from the past, what kind of relationship Tatsuki Fujimoto will establish with his readers?

Translation Shinichiro Sato

Photography Yohei Kichiraku