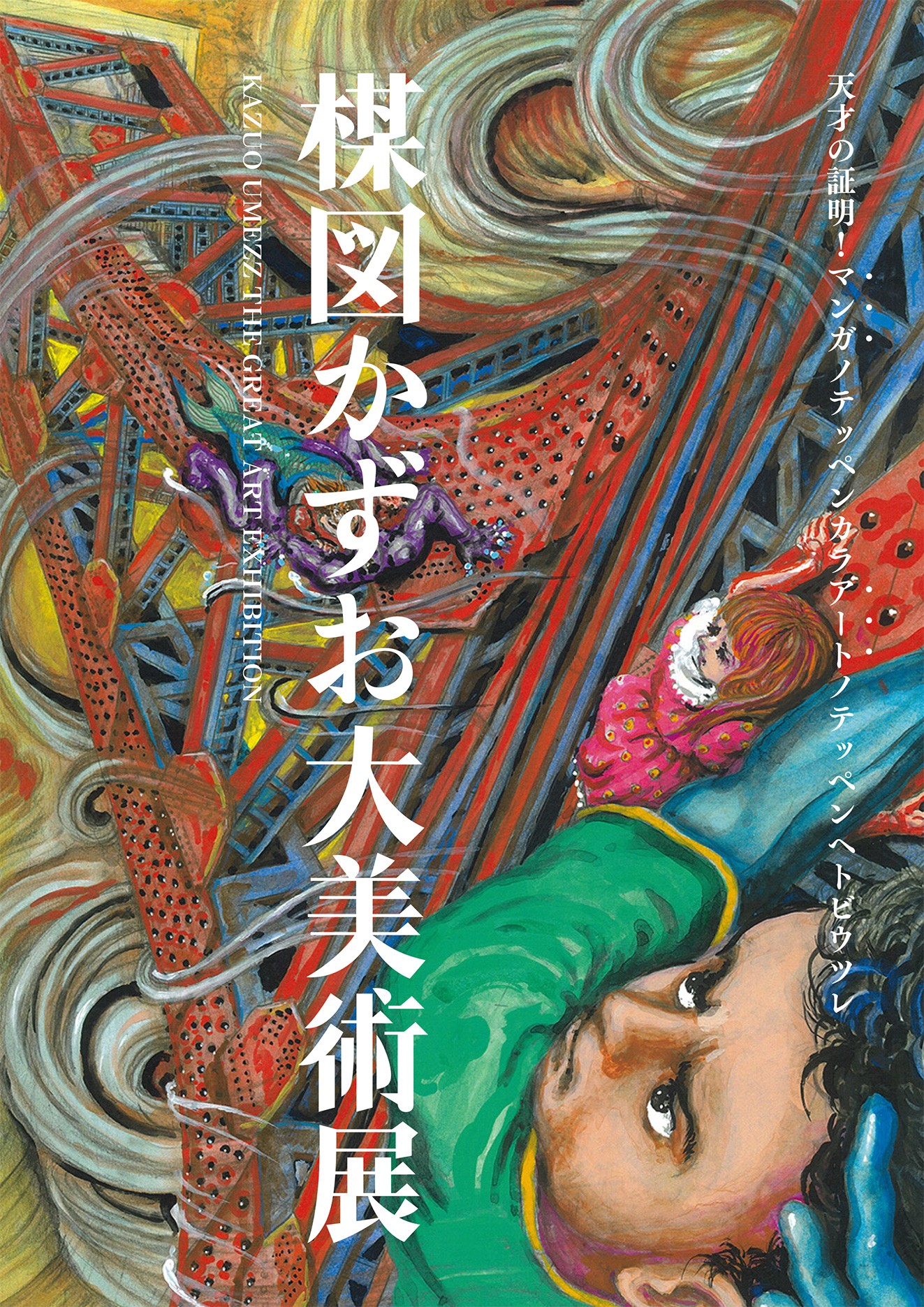

Kazuo Umezu, manga artist and author of iconic mangas such as The Drifting Classroom, Watashi wa Shingo, and Fourteen, showcased new work for the first time in 27 years. Umezu, who’s welcoming his 86th birthday this year, has entered new territory through his new series of 101 paintings. “Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition,” held at Tokyo City View at the beginning of the year, was met with great success. Starting from September 27th, the exhibition is now available at the Abeno Harukas Art Museum in Osaka.

Winning the Heritage Award for Watashi wa Shingo at the Angouleme International Comics Festival inspired the manga artist to create his 101 paintings titled “Zoku-Shingo: Chiisana Robot Shingo Bijutsukan.”

Once you read this interview, there’s no doubt you’ll feel the esteemed Umezu’s energetic spirit.

In the latter half of the interview, Umezu brings up Taro Okamoto, who believed humanity hadn’t progressed. He created the primitive-feeling Tower of the Sun and blew Expo ’70 out of the water, which had the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind.” You’ll see that Umezu shares a similar sentiment and soul, too.

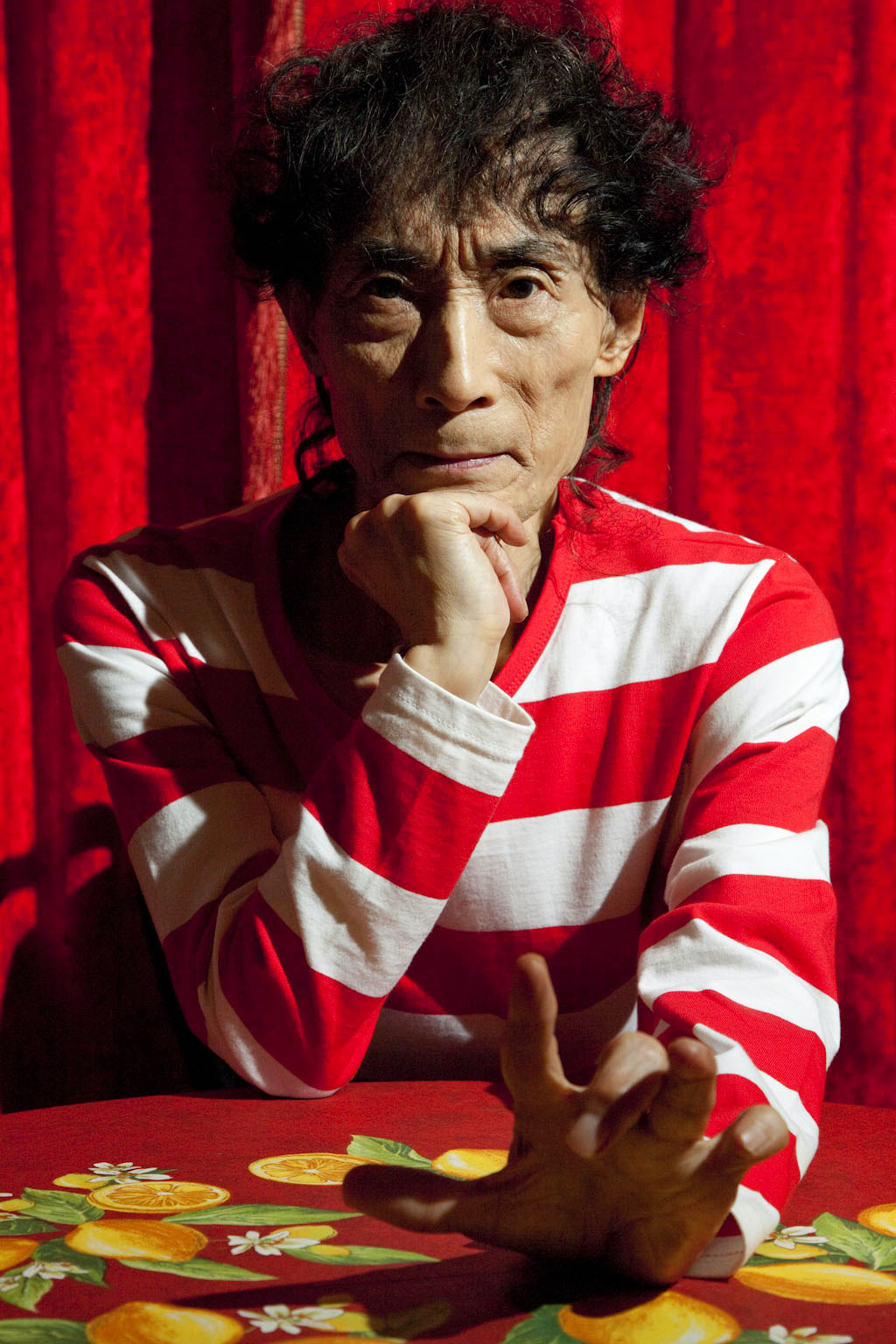

Kazuo Umezu

Kazuo Umezu was born on September 3rd, 1936, in Wakayama prefecture. He decided to become a manga artist in fifth grade after becoming inspired by Osamu Tezuka. Umezu made his professional debut in 1955 at 18 with Mori no Kyodai. He gained nationwide recognition as a horror manga artist with titles like Nekome no Shojo and Reptilia. In 1975, he won the 20th Shogakukan Manga Award for The Drifting Classroom. Umezu published hits like Makoto-chan and Orochi afterward. In the 80s, he published mangas that depicted the near future, like Watashi wa Shingo and Fourteen. He’s gained an international fanbase with his creative world-building. “Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition” is now being held at Abeno Harukas Art Museum in Osaka.

http://umezz.com/jp

The predilection for using pretty colors

――It’s been a while since your exhibition, “Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition,” was held in Tokyo from January to March this year. Have you received any responses and thoughts about the exhibition?

Kazuo Umezu (Umezu): People talk to me a lot whenever I’m walking down the street, so it seems like many people went to the exhibition. No one has told me it was boring (laughs).

Everyone seems to have been moved by the exhibition; it gives me strength whenever they say words of encouragement in a lively way. It makes me happy when someone says, “It was great!” People saying hello or coming up to me proves they pay attention to my work. It’s reassuring that many people are like that. It makes me feel like it’s all been worthwhile.

――I also went to “The Great Art Exhibition,” and the thing that stuck with me is how beautiful the paintings and colors you used were. It seems like you made a point to use both primary and vibrant colors. Did you pay special attention to anything in terms of painting or incorporating colors?

Umezu: I realized I’m the type who tries to use beautiful colors to draw.

I used such colors to draw in middle school too. Aside from colors, I was also particular about using various kinds of paint. As a middle schooler, I would use red ink for red, dyes for blue, and food coloring for yellow.

I used acrylic gouache for “Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition.” I was excited to choose which colors to use because they were all so beautiful. The dark colors are pretty too. Each color has a distinct beauty, but when you mix another pretty color, both colors can hold their own. That’s why I did my best to use beautiful ones.

Some say you shouldn’t mix different colors or apply paint onto a canvas without anything else in art, but modern-day paint is pretty [so it doesn’t matter].

――Paints do look more beautiful nowadays.

Umezu: You can get paint that already looks like it’s been mixed, so you don’t have to do extra work.

The theme for the exhibition is “A series of paintings.” I could draw whatever I wanted, but it was inevitable for me to create rules. If a random color popped up in a series of connected paintings, people would ask, “What’s going on?” One rule was to use red and pink for Marin, a girl, and blue and green for Satoru, a boy. I used those colors everywhere they went in the paintings. With that said, the color of his pants is yellow in some instances and brown in others.

It wouldn’t be a problem if each painting were a complete piece, but using disjointed colors wouldn’t have worked since the paintings are all connected; the entire series wouldn’t be coherent and impactful. I’m sure there are rules to art that people from long ago created, but I think you can develop your craft by creating new ones for yourself.

“Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition” Tokyo (Closing), Tokyo City View (Roppongi Hills)

Wanting to make people thrilled and surprised

――You held your exhibition first in Tokyo and then in Osaka in September despite the pandemic. What was the significance of holding a big exhibition during times like these?

Umezu: I, too, was thrown into the pandemic, so I gave this some thought. Even in a world with covid, a recession, and conflict, we will always want stimulation and fun as long as we’re alive.

As the title of the paintings suggests, to feel “Zoku [zoku]” is to feel excited in any situation, even if the world is upside down. We should have things that draw us to them and make us go, “Wow! That’s so cool!” We need spiritual nourishment no matter the situation.

But even without thinking about all that, I still believe we need things that excite us no matter what. I painted with the desire to make everyone excited and surprised, regardless of covid. I feel like your focus shifts on what you’re looking at [if it’s interesting], thus making you forget about your pain, even if it’s just for a second. That’s essential.

――I feel the same way. I read in another interview that the words “human deterioration” popped up when you were working on “Zoku-Shingo: Chiisana Robot Shingo Bijutsukan.” How did you try to reflect those words in your work?

Umezu: The paintings depict somewhat of a competition between robots and humans. I just thought that humans would deteriorate the more robots advance because they wouldn’t be able to keep up with robots. I feel like people are convinced that everything should and will progress. They don’t think about deterioration.

I started thinking about this because people cause harm to others daily. I’m sure each person has their reasons, but seeing such things made me think, “Well, we’re going downhill.” When things are progressing, things go in a good direction. But things are going in the wrong direction, making morale low. I feel like the future is about returning to nature. Once there’s no civilization left to progress, the only choice would be to return to nature. We’ve reached a point where the forefront of progress is almost out of reach. Modern progress is about numbers. Once we get results using them, we won’t be able to revert the process. Things will only continue moving forward. We listen to science telling us what to do and operate accordingly without understanding what’s at stake. If electricity stops working, progress will also stop. Then, we humans wouldn’t be able to do anything. We’d disintegrate. That’s why I feel like the direction we’re heading in is that of deterioration. I call it the reformation of deterioration (laughs).

“Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition” Tokyo (Closing), Tokyo City View (Roppongi Hills)

I won’t continue drawing unless I hear a voice inside me saying, ‘That’s good”

――(Laughs). Change of topic: you’ve been living in Kichijoji for a long time. I also live in an area not too far from you, and I sometimes see you walking around. Does Kichijoji influence your creativity or ideas?

Umezu: Not at all. Whenever I draw something based on Kichijoji, it’s more like a journal of my everyday life. Rather than it being dramatic, it’s more like nonfiction. But that’s not what I strive to do. Kichijoji, San Francisco, or New York; where I live doesn’t matter because I live in my head. However, I will say that Kichijoji is convenient for shopping (laughs).

――Your mangas are highly appreciated abroad too. How do you think your foreign audience perceives your work? What sort of responses do you get from them?

Umezu: I’m not sure since I’ve never met them, but some movies make me say, “They took that from my work,” so I think my work is recognized abroad. I also read a Spanish book that was written about me.

I also read God’s Left Hand, Devil’s Right Hand in Japanese because I heard the translated version was published abroad. I don’t read my own manga once I’m done working on it. So, when I reread it, I was like, “Wow, look at that! That’s amazing!” I read it from the perspective of a reader. Not to toot my own horn, but it was impressive. I thought about watching the film adaptation, but I stopped because I felt like my manga would win (laughs).

I sound like I’m praising myself, but that’s how impactful the manga seemed to me. People might hesitate to read it because the human aspect of it sticks out, but the story is excellent. My career abroad has only just begun.

――It’s as though your mangas predicted modern-day society. In Watashi wa Shingo, you illustrated the computer, for instance. I still get surprised when I read your work today. How did you come up with this idea? Amid an era where so many things are happening, what does progress and the future look like to you?

Umezu: People still believe advancement is inevitable but must realize they have the wrong impression. That’s the only way to improve the future. At one point, I realized the job of the manga artist was to draw what would happen next.

I used to think of different stories in my head, but I never thought about reality or what was happening in the world. Looking back, every manga I drew aligned with whatever became popular afterward. There’s no other way to say it; my work has remained relevant through the years. But it’s not like I predict the future using logic.

――What was the process behind Watashi wa Shingo like?

Umezu: When I drew Watashi wa Shingo, there was a curse of mangas with a lot of research that went into them not doing well. I knew the manga wouldn’t perform well if I half-heartedly looked into robots and incorporated that into the story because of the curse. I used photos taken at a factory to reference realistic designs, but back then, you would see rows of square computers that weren’t interesting at all. I had to come up with an exciting design on my own. The robots at the factory differed significantly from what I drew, but I asked computer experts whether the robots I drew would function. I tried my best to merge my imagination and reality.

I won’t continue drawing unless I hear a voice inside me saying, “That’s good.” Once I hear it, I draw obsessively, no matter what anyone says. You run into hindrances if you work on one manga for six years. If you pay attention to them, you’d be discouraged, and your work will be confused. It’ll fall apart because of the lack of cohesion. Even if whatever I’m working on isn’t well-liked, once I hear my inner voice saying, “That’s good,” I have to trust it and complete the process.

――You stick to your gut once you start drawing.

Umezu: Another good thing is that I feel like there’s something other people and I have in common. As long as my intuition is correct, the things I like will begin spreading among the rest of society. I believe this is something that happens to me.

Whenever I draw something new, the content naturally becomes about the future. I foresee future events before I even know it. I feel like having a childlike spirit plays a significant role in this. Just because something is made into reality through science and logic doesn’t mean a new story is born. If you write about what happens in reality, nothing is exciting or fun about it.

Truth exists, of course, but it’s different from fiction. I want to create interesting stories. Having a childlike spirit is a profound thing. It’s a great thing I picked up. My stories feature children, so there’s a connection (laughs). The difference between adults and children is that adults might think something is childish, but children might think the opposite. Whenever I draw stories, the direction is usually determined by the protagonist. The age kept getting younger and younger, and in Fourteen, the protagonist became as young as three years old. That’s no longer about having a childlike spirit, as three-year-olds are children (laughs).

――True (laughs).

Umezu: I recently read an article in which Yasunari Kawabata-san said, “You need to have a childlike spirit.” I felt there was a disconnect because his works were moving and dealt with everyday subjects. But I realized you need a childlike spirit to have an artistic and dramatic one, or else you wouldn’t be able to create a good piece of work.

That’s why having a childlike spirit is an important criterion. But that doesn’t mean I’m disregarding nonfiction. Everyday life is nonfiction, so you must connect the two to establish a narrative. How that could look depends on the artist’s skills.

――That allows the artist to show off their skills.

Umezu: Old mangas have a childlike spirit, but recent mangas are about jobs, to put it simply. I believe mangas should have a wonderful youthful spirit; they shouldn’t portray work. It’s vital to have both a childlike spirit and polish. In that sense, I guess I’m the best at what I do (laughs).

The content of God’s Left Hand, Devil’s Right Hand, is chaotic, but I feel like it represents a childlike spirit. It’s like, “Now, this is what I want to draw! This is it!” The term youthful spirit can also be linked to artistry, which is why it resonates with me to this extent.

With that said, I’m not making fun of reality. I can’t change reality, so all I ask for is to have a free inner world. If we’ve been able to evolve as humans regardless of the era, then I want to say that I’ve used my imagination to the fullest to create things.

“Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition” Tokyo (Closing), Tokyo City View (Roppongi Hills)

“I painted to the best of my ability, so I want everyone to see my works”

――Your exhibition in Osaka opened in September. What part of the exhibition do you want to highlight for prospective visitors? Also, what’s your image of Osaka? Do you have any memories there?

Umezu: I’m so grateful people want to visit my exhibitions many times. Those who saw my paintings in Tokyo and those who haven’t will find something about the paintings that move them. I painted them during covid, so I’m sure there’s something people could be drawn to. I hope they can look for that element. I feel like something about the paintings will resonate with people and make them say, “Oh wow, look at how detailed this part is!”

When I think of Osaka, I think of a big city. I’m from Gojo, Nara, so Osaka is the closest big city for those from Gojo. When I started drawing manga, I submitted a story to Shojo Book published by Shoeisha, and they decided to feature and serialize it. Haha Yobu Koe was serialized for a year, and I also drew other stories, but I felt that I still didn’t have enough skills. I brought my story to a publisher in Osaka because I wanted to start over. I drew mangas in Osaka until that publisher went out of business. After that, I came to Tokyo.

――I didn’t know you drew manga in Osaka!

Umezu: Unlike the culture in Tokyo, Osaka’s culture has no pretense. There were many unashamedly childlike mangas, so that was fun (laughs). People said pulp fiction books were low-brow, but that made them good. Yaneura 3 Chan is funny. I feel like mangas in Osaka were more open with their emotions, and the same could be said about the people there. It’d make me happy if people in Osaka could view the exhibition in a different light from people in Tokyo. I hope they could see the humor in my work and be like, “That was funny,” or “That part was a gag.” Some might also see the scary parts as a gag (laughs).

I painted to the best of my ability, so I want everyone to see my work. When I think of Osaka, I think of Taro Okamoto-san, who was powerful and brilliant. I have my strengths in other areas, and I can proudly say I can come up with stories like no other! I’m just as good as Taro Okamoto-san! Picasso drew comics, but I’m just as good as him! I’m just as good as anyone else! If people could view my paintings thinking about how I feel just as capable as people from Osaka, then I believe they could feel even more excited (laughs).

■Kazuo Umezz The Great Art Exhibition

Dates: ~ November 20

Venue: ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum, Osaka

Address: ABENO HARUKAS 16F 1-43 Abenosuji 1chome, Abeno-ku, Osaka 545-6016 JAPAN

Hours: [Tues. – Fri.] 10:00-20:00, [Mon., Sat., Sun., & national holidays] 10:00-18:00

*Last admission is 30 minutes before closing.

Admission: Adults ¥1,700, University students / Senior high school students ¥1,300, Junior high school students / Elementary school students ¥500, and kids under 12 are free

Web: https://umezz-art.jp