Culture can be born out of a specific time and place, and yet, it can possibly possess the ability to become timeless. In this series, “時音” TOKION invites people who are shaping culture today, to talk about the past, present, and future.

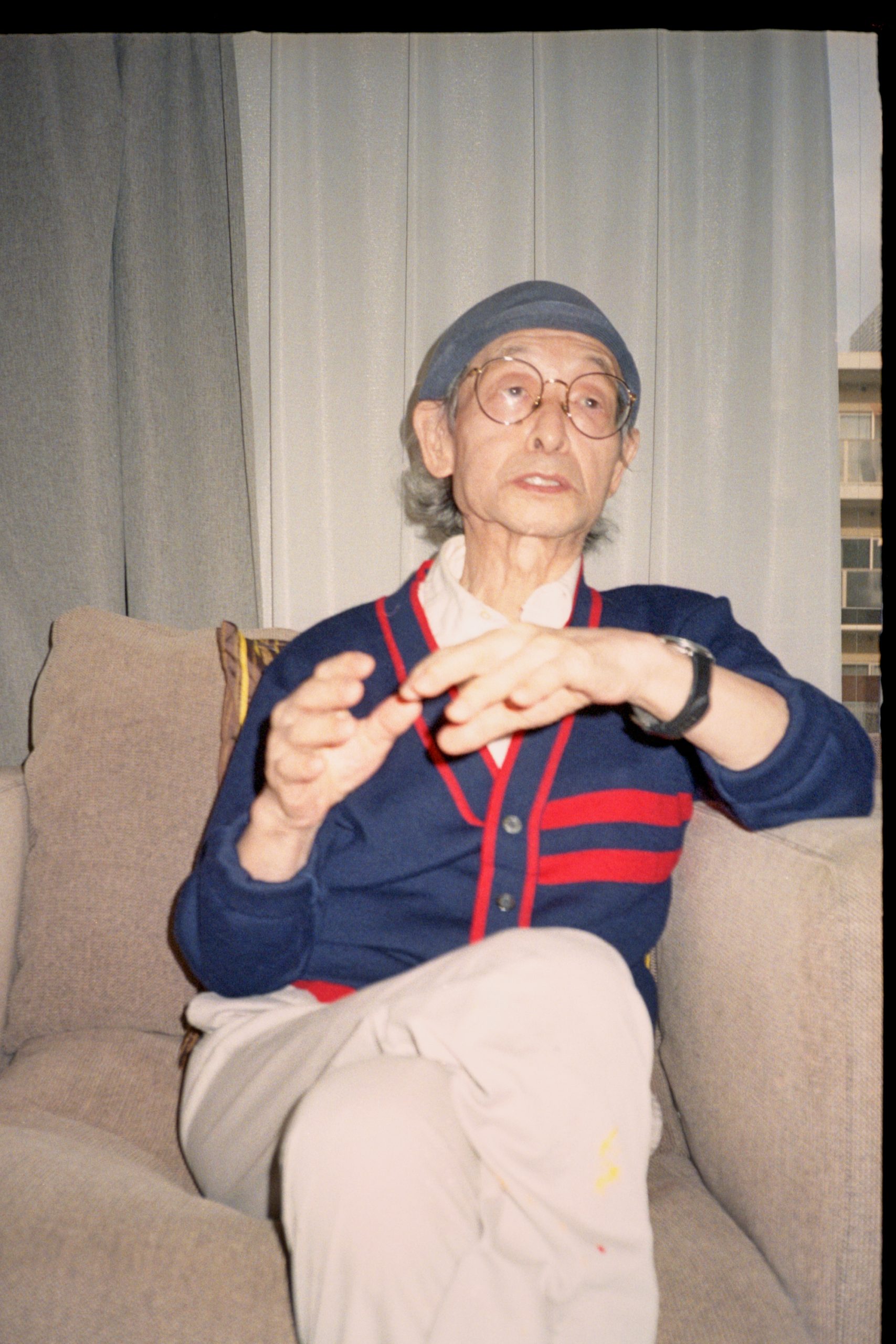

The 19th installment is about artist Keiichi Tanaami. Many of his collage-based works represent the deep unconscious, bolstered by his professional editing skills. The colorful mass of details is made of eloquent paradoxes, which leaves the viewer stunned.

In recent years, Tanaami has collaborated with fashion brands such as Adidas and Junya Watanabe and created album covers for musicians like Nina Kravitz and Aki Yashiro. As such, he continues to push the boundaries of his artistic career.

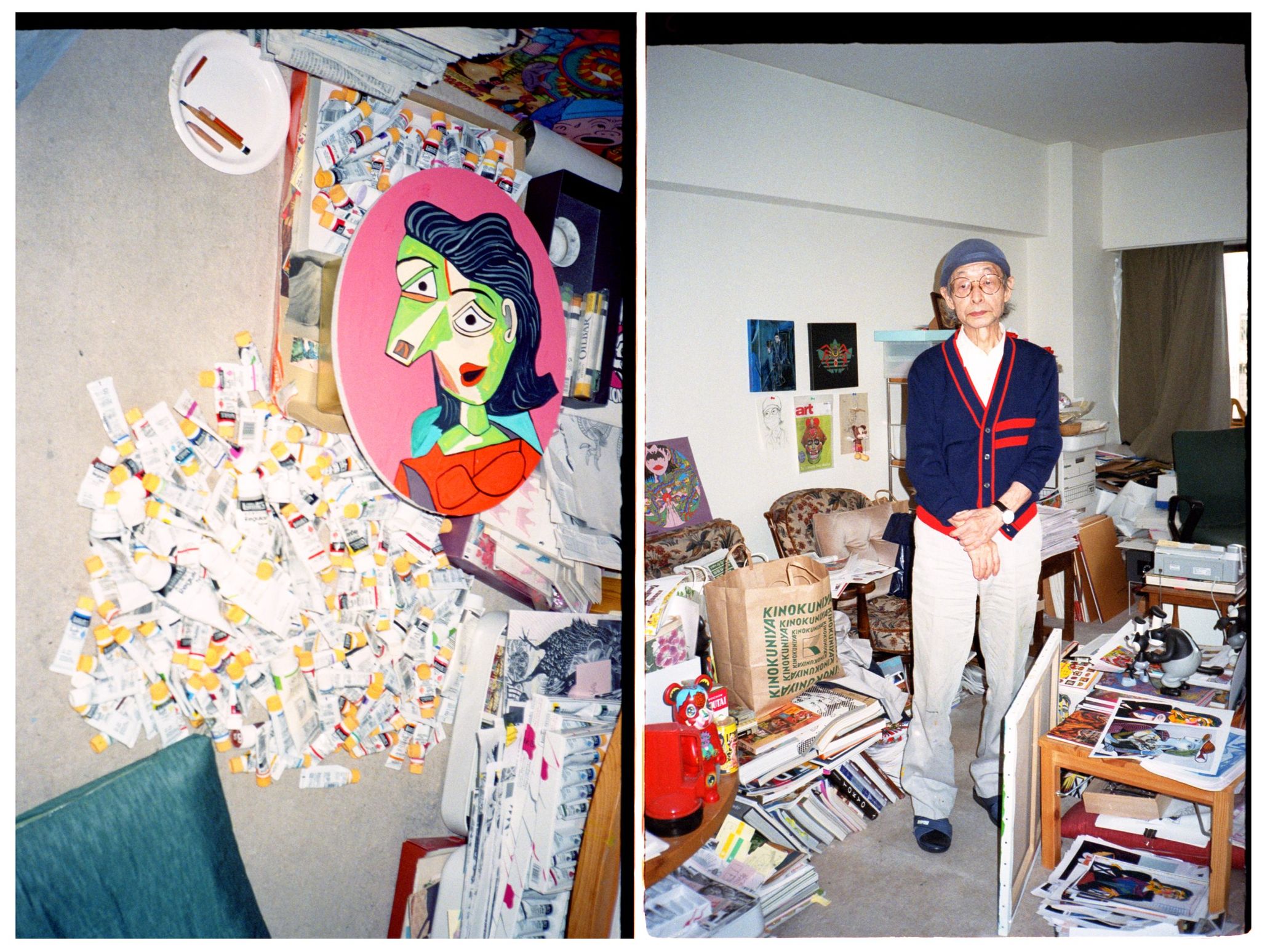

Instead of growing weaker with age, he bursts with vitality like geothermal energy. Tanaami says he has more creativity and wisdom today than his younger years. His life is a pursuit of light amid an uncertain future, a compass that shows the struggling world the way. We spoke to the artist in hopes of unearthing his core creativity and spirit in his studio in Aoyama, surrounded by his monumental works.

Keiichi Tanaami

Keiichi Tanaami was born in Tokyo in 1936. Since graduating from Musashino Art University, he’s worked as a graphic designer, filmmaker, and artist from the 60s onward without being limited by mediums and genres. His recent major exhibitions include “The World Goes Pop,” held at Tate Modern in London in 2015, “Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami,” at Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and “Memorial Reconstruction” at Nanzuka in 2020. Tanaami’s works are on permanent exhibit in globally renowned museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

At the intersection between art and design

–It’s my understanding that you honed your masterful collaged pieces, the foundation of your work, through a steady career in graphic design. Could you walk me through the changes in your career and art?

Keiichi Tanaami: After I graduated from the department of design at Musashino Art University, I worked in advertising at Hakuhodo. After roughly three years, I quit and mainly focused on design. My work during my Musashino days was mostly design-related, but I had already developed an interest in art then. My parents and relatives strongly advised me not to pursue art because they felt it was hard to make a living off it. I chose a career in design as a result of being realistic. I still wanted to work on my art skills, but I didn’t have enough time to do it; I had a dilemma because I felt like I was leading only a half-fulfilling life. Most of my friends at the time were artists rather than designers, such as Tomio Miki, Shusaku Arakawa, Ushio Shinohara, and Genpei Akasegawa. They belonged to the so-called “Anti-Art” movement. I couldn’t help but be in awe of who they were and how they lived as they strived for something completely different from conventional art.

–Were other people in your circle involved in commercial design and anti-art?

Tanaami: No, they weren’t. Professor Hiromu Hara of Musashino Art University, who was a leading figure in the field, always told me to focus on design rather than something as crude as drawing. And yet, I kept drawing, but it wasn’t like I didn’t enjoy designing. I constantly thought: “There’s no point if I don’t enter a space where I can express myself freely if I want my work to reflect my way of living.”

I spent my youth struggling with that, but one day, I realized the great importance of the discipline of design in art. Since then, I’ve incorporated design techniques and methods in experimental filmmaking and drawing. In other words, my design process plays a significant role in my artistic expression.

–Did you feel a sense of confidence in your work when you came across pop art, seeing as you worked in commercial design and anti-art and experienced the fusion of art and design?

Tanaami: I do think so, yes. For instance, Andy Warhol made books and films aside from paintings. His work didn’t strongly influence me as a painter per se, but I related to his thinking behind his creation process, the technique of directly incorporating the editing process into the final product, and the principles behind his pop art paintings. If anything, I was able to understand my anti-art friends’ ideologies through Warhol.

–How did you meet Andy Warhol?

Tanaami: I didn’t meet him until much later. There was only one foreign-language bookstore in Ginza, which my friend Gyu-chan (Ushio Shinohara) and I often visited. One day, the critic Jinichi Uekusa, a regular customer of the bookstore, dropped his books as he tripped down the stairs. Gyu-chan and I helped him. As a token of his appreciation, he told us about emerging art forms and artworks in America while showing us a copy of ARTnews. There were photos of pop art pieces like those by Warhol and Lichtenstein, and I was shocked. I thought, “I didn’t know people accepted this type of art.”

–Did you sense a design element from pop art?

Tanaami: Warhol and Lichtenstein used materials from commercial mediums and mass media to produce art. That was similar to what I would do as a graphic designer, so I started thinking I could also create fine art while maintaining my position as a designer.

–You met Warhol in person later on, yes?

Tanaami: Warhol was having a solo show at Daimaru, a department store, in Tokyo for the first time in 1974. I was asked to do the art direction for NHK’s one-hour television special. I wanted to use his face for the TV show’s visuals and asked the cameraman from NHK to photograph him. However, Warhol was in a bad mood from start to finish because he was tired from traveling, so we couldn’t go through with the photoshoot. So, I changed my initial plan and decided to create a collage from my own animation.

I sent him the completed footage, and he loved it, even though my design didn’t use Warhol as a motif. I had been fascinated by him before that point and was happy when I heard he was having a show in Tokyo. I feel like the final product naturally reflected those thoughts.

–You’ve had many Japanese and international collaborations with fashion brands such as Comme des Garçons and Adidas. You’ve also made artwork for musicians. How do you utilize the design framework when you collaborate with others?

Tanaami: Whenever I’m working on a collaboration, I don’t provide a visual the client wants and leave it at that. Collaborating on the overall design is essential, considering that I have a lot of experience as a designer. I start by putting out ideas, even if it’s a t-shirt project. I’ve spent many years painting and designing simultaneously, and today, I don’t feel like a designer anymore. I now feel like my job is that of an artist. Thankfully, I get fun job offers, so I’ve never felt distressed about it. I especially like working with clothes because they move. Great projects inspire my artistic expression, so they have a positive synergy.

The inspiration behind imagination

–A clear source of inspiration for your art seems to be your childhood experiences and memories of war.

Tanaami: I experienced the horrors of war when I was small, and looking back now, nothing compares to how shocking it was. None of my other memories are as intense as war. That’s how terrible it was. You might understand what I’m saying a little bit if you think about the situation in Ukraine: I saw people dying every day like it was normal. I wouldn’t have seen anything like it if it weren’t for war. Because I saw people dying as a child, the memories are engraved in my memory. I can’t erase them. I don’t try to depict war in an obvious way, but I have these memories I haven’t fully processed in the depths of my heart. Those memories present themselves subconsciously in my work.

–On one hand, you were influenced by American culture, but on the other, Japan fought them in the war. How did you come to terms with that?

Tanaami: When I started middle school after the war, I used to go to a small movie theater near Meguro station since there was nothing else to do. They specialized in American B-films, probably because of their wishes, and would play what you’d call propaganda films.

I repeatedly heard my parents talk about how America was the enemy, so I naturally had a negative view of the country. But I fell in love with the country as I started watching films that captured what made America so good, such as those by Disney and the Fleischer Brothers. I’d say there were quite a few young people who admired America.

–Your works feature American fighter aircraft but in an ironic tone.

Tanaami: I couldn’t fully understand the meaning of war as a child, but I saw suffering every day. My complicated and conflicted emotions, namely my admiration and negative feelings toward America, show up in my work.

I strongly remember the lunch boxes the American army would provide for us. We would get one parcel per household once a month because food was scarce after the war. One of the items was the lunches packed with food the American army would eat. They would place bright white bread, fish, sausages, fruits, and snacks in a balanced way in these nice lunch boxes. I was captivated by their beauty.

Also, there was what you would call a Western-style house next door, and an American commissioned officer’s family lived there. They had a small girl. I vividly remember how a maid who used to work there often gave me sweets like chocolate and gum that the girl used to eat. I became mesmerized by the American lifestyle through them.

–I have a negative image of war, as it destroys people’s everyday lives with its utter senselessness. It’s a reality that surpasses reality. Do war’s negative power and energy come to the fore in your work?

Tanaami: In many cases, the art I make starts to resemble the image I have of war, even though that’s not my intention. One example is my use of color. After the war, I returned to Tokyo from Niigata, where we had evacuated, and looked over the city from the top of Gonnosukezaka at Meguro station. I knew the city very well, but the trees and buildings were gone. Everything had changed entirely. In front of me was a red, scorched earth, and beyond the horizon was the most transparent blue sky I had ever seen. It was shocking to see the absence of things that were there every day and the landscape’s two different colors, red and blue. That experience will always influence the colors I use to draw and paint. And the memory of what I saw will always come back to me.

–One of the features of your art is your use of rich colors. Where do you get that inspiration from?

Tanaami: It’s said that childhood experiences influence one’s sensibilities regarding color later in life, which applies to me too. My grandfather ran a textile shop in Kyobashi, and his house was behind Takashimaya Department Store. I spent my childhood in an environment full of color; the city was decorated with neon signs, and Takashimaya was my playground. He had piles of textiles at home, and among the piles were labels you’d put on jackets. Back then, labels were so intricate. These fantastic patterns, like camels, were embroidered with gold or silver threads, so I never got bored looking at them. I feel my childhood experiences involving color inform my use of color today, which can be seen as excessive for some.

The shift in creating art during covid

–How did you spend your time when covid restrictions were strict? Did that period influence your art?

Tanaami: When I turned 70, I thought it would be hard to continue working as an artist, but my desire to express myself is stronger than ever. It’s become stronger because I was limited in what I could do due to the pandemic. I used to think you have a lot of creativity and wisdom in your youth and that they decline as you age, but it seems that isn’t the case for me. I’m sure I’ve grown physically weaker, but it’s so strange how I have more creativity now compared to my 30s and 40s. I come up with things I want to express one after the other, and my hands move on their own accord. Even if I have lower energy levels now, it doesn’t feel like it. I considered slowing down around my 50s, but that’s not even a consideration for me anymore.

–Does one of the reasons for that stem from how you had more time to think about things because society paused due to covid?

Tanaami: Perhaps. Looking back, I couldn’t spend time on what I wanted to do before covid because I worked across many fields. People wanted me to make quick decisions because of deadlines. But I had more time to myself once many things paused because of covid, allowing me to focus on my thoughts all day. That had a massive effect on me. Now, I come up with ideas I never had before, which has broadened my creative horizons.

Also, I started replicating Picasso’s “Mother and Child” during the pandemic. I first tried to paint around ten of them, but I had painted hundreds before I knew it. I’m not trying to study some skills from Picasso’s work. I realized that by looking at his work while I paint, my thinking never ceases to end. I can discover an array of things through that. For instance, Picasso drew strange-looking hands, and I began to understand why he did this the more I copied his work. It’s not like I was “possessed” by his spirit, but it was the first time I painted while paying acute attention to how his line of thinking started making sense to me. It was an exciting experience.

–I was under the impression you worked on your design-related projects using spontaneous ideas. But it seems like you distanced yourself from that method and created the pieces for your exhibition, “A Mirror of the World,” using ideas that came to you effortlessly and naturally.

Tanaami: When I started replicating Picasso’s “Mother and Child,” I studied it very well to convey the composition and details with accuracy, but I eventually began distorting the paintings a bit. From there, I got many ideas I wanted to test out, like what it’d be like if I painted “Mother and Child” without looking at it. It felt like I was experimenting over and over again. That didn’t change that I was copying his work, but I could tell my paintings were going in a new direction. It’s fun when your methodology becomes more diversified.

Picasso’s work has an infinite pool of different critiques, but we won’t see a creative genius like him that soon. Some artists’ works are fun to replicate, but I never run out of things to think about when I’m copying Picasso’s work. It makes me think things like, “Wow, Picasso’s posthumous works became Picasso himself.” It’s a scary thought, in a way, but I can’t stop painting. That’s what made him a talented artist. It’s said he painted close to 40,000 pieces. It’s impressive how he had the energy to do that. Apparently, he was fast at painting, and instead of simply mixing and creating colors on his palette, he would apply pure colors onto the canvas and paint directly on there.

When I worked as a designer, I didn’t have the habit of spending much time on and thinking about my work. I worked fast; I would get an idea of what I wanted to do in a meeting. I didn’t dig deep into my thoughts or struggle through trial and error. When I’m replicating Picasso’s work, the time I spend in front of the canvas is the time I think. By doing this, I get more ideas and feel more motivated. I feel like this for the first time because I stand on the shoulder of the giant that is Picasso.

Meeting Fujio Akatsuka

–I see that your studio has collages incorporating Fujio Akatsuka-san’s characters and expressions.

Tanaami: I’m an Akatsuka fan through and through. I used to envy him and developed a complex because I couldn’t become a manga artist even though I wanted to. We’re around the same age, but he was a massive star. Whenever we met, I would talk to him like he were a teacher, so our conversations didn’t flow. I wanted to be closer to him, but I put up a wall, so I sadly couldn’t foster a friendship with him.

I met Akatsuka-san through the film director Koji Wakamatsu-san. Wakamatsu-san used to go to a bar I frequented, and he introduced me to Akatsuka-san, who was already a star at that point. I was nervous, so I sat and listened to the two’s conversation. Wakamatsu-san said he needed help because he didn’t have enough funding for his film. Akatsuka-san took a couple of sips, thought about it for a while, and said, “Yeah, sure.” Not only was he a successful manga artist, but he was also a tremendous person.

–It sounds like he had a big heart beyond the average person’s understanding.

Tanaami: Yes. We started seeing each other daily at the bar, but I always saw him as superior. He often brought a young man wearing a necktie, and that was Tamori-san. He had a bit called “Hadaka no Show,” where Akatsuka-san would lie on the floor naked, and Tamori-san would pour wax from an absurdly thick candle on him. Akatsuka-san’s body would get beet red, and he would writhe and yelp in pain. That went on every day. It was so scary (laughs). The bar had a candle set just for him called the “Akatsuka set,” and they would perform their show everywhere. I was so impressed by him when I watched what he did. Akatsuka-san was an extraordinary man.

I was just in awe of him. Akatsuka-san was a kind person without a single bad bone in his body. He was pretty similar to my friend Gyu-chan, and I still feel like we could’ve been closer to one another had I been more open.

■A Mirror of the World

Date: November 12th to December 25th

Venue: Nanzuka Underground

Location: Jingumae, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 3-30-10

Time: 11 AM to 7 PM

Closed on: Mondays, Holidays

Entrance fee: Free

Official website: https://nanzuka.com/

Photography RiE Amano

Interview Akio Kunisawa

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)

Translation Lena Grace Suda