GEZAN

Formed in Osaka in 2009, GEZAN is an alternative rock band consisting of Mahito the People (vo., gt.), Eagle Taka (gt.), Yakumoa (ba.), and Roscal Ishihara (dr.). In 2012, the band moved its base to Tokyo and has been active throughout Japan based on its unique perspective. They run Jusangatsu, a label that sends out a variety of domestic and international talent. Since 2014, they have been holding the “Zenkankaku-Sai Festival,” a donation-based outdoor festival organized by Jusangatsu, which is free admission, with the idea of “letting people decide the value of fun for themselves.” The band released their fifth full-length album KLUE in January 2020, and in May 2021, they were joined by a new bassist, Yakumoa, and performed in “FUJI ROCK FESTIVAL”. The band released their first full-length album in three years, Anochi, produced with Million Wish Collective, on February 1, 2023.

http://gezan.net

Twitter:@gezan_official

http://mahitothepeople.com

Twitter:@1__gezan__3

Instagram:@mahitothepeople___gezan

GEZAN, a rock band led by Mahito the People, have released their sixth full-length album in three years, Anochi. While their previous album, KLUE, brought about innovation in dance and physicality by setting the tempo of almost all songs at 100 BPM, this new album brings in the Million Wish Collective, a voice ensemble consisting of 17 members, and results in an unprecedented work filled with countless “voices.”

The most significant change they have gone through after the release of their fifth album was the pandemic outbreak. The release tour was canceled due to major restrictions that prevented the band from performing live as they had done in the past. Furthermore, the world has been changing at a dizzying pace with the global spread of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, the Russian military invasion of Ukraine, and the shooting death of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Bassist Carlos Ozaki left GEZAN. However, during the pandemic, there were also new challenges for GEZAN, such as the “Zen-Kankaku-Sai Festival”. Above all, Yakumoa joined as a replacement bassist, and the band also met Million Wish Collective. It was in this ever-changing world that they created Anochi.

We interviewed Mahito the People, a core member of GEZAN, to find out how the pandemic affected the band, what possibilities he believes alternative music has in these turbulent times, and why the band focused on the theme of “voice” for their new album.

The loss of physicality in the COVID-19 pandemic

–In January 2020, just after the release of your previous work, KLUE, the pandemic occurred. How did the pandemic impact GEZAN’s activities?

Mahito the People (Mahito): I think the biggest thing was the loss of physicality. After the onset of the COVID pandemic, we could no longer do live shows. A Live show meant more to us than just making a financial profit, it was rather a place of communication where we could share the same water, so to speak. In the same space, we and the audience would salivate and sweat together, inhaling and exhaling the droplets together. That was very important for the band.

Right after the start of the pandemic, online live shows became popular. They can deliver visual/audio information similar to that of a live show, but they lack the exchange and collision of temperatures that is an essential part of a live show. I had been salvaged by such physicality, so I became terribly unbalanced. So did the band members. Carlos’ departure from the band was also due to the loss of pace in our daily lives, so in that sense, the pandemic had a great impact on us.

But at the same time, what was lost gave us an opportunity to question what was important to us. We tried to do some online live shows ourselves, and we even did some interviews online. Words like “thank you” and “good-bye” are only a few words when written, but when spoken face-to-face while sharing the vibration, the same words can have a completely different meaning. This kind of thing still meant a lot to me, so I realized what I had truly relied on.

— In May 2020, you held the “Zenkankaku-Sai (Sai here refers to a kanji 菜 meaning plants and vegetable)” instead of the “Zenkankaku Festival. I myself was watching it in desperate hope, and at that event, Roscal Ishihara challenged a 30-hour drum marathon, pushing his body to the limit. I think it was also an attempt to deliver a certain kind of physicality and live feeling through the Internet. What was it actually like for you?

Mahito: At that time, there were strong calls for “stay-at-home,” and we felt as if the world we live in is all about what is inside our rooms. Of course, there were people who had to leave their rooms, but inevitably we spent more and more time exposed to information. The information provided on cell phones and TV about the number of infected people and the updates on the development of vaccines acted just like a god, and we had no choice but to pray to it. I got tired of that.

Rather than trying to communicate something to people, I wanted time to just focus on the movement of the bass drum, snare, hi-hat, and the physical strength of the Roscal, without worrying about what was going on in the world. So I was very comfortable during those 30 hours. I tried it because I thought it would be possible to convey a kind of temperature through an online show, and I don’t think it was unsuccessful, but I don’t know now if we should dare to do it, going through all that trouble. It was so hard that it killed us (laughs). And right after it was over, there was the BLM movement that was growing increasingly visible. Even though I felt like I had been saved somehow by blocking out information, this movement confronted me with the reality that the times were moving in such a situation. I felt like I couldn’t run away even if I wanted to. So that experience had these two sides.

–Some musicians said that “Stay-at-Home” allowed them to have more time for recording and production, while others said that it strengthened the unity of the band. Was there any positive impact on your band that was brought about by the pandemic?

Mahito: Well, as far as we were concerned, I don’t think we could behave consistently. I would be lying, if I said the pandemic brought the band member closer to each other. One of two aspects of making an album and performing live was having something become a message through singing something, and the other half was confronting the monster inside me through shouting and strumming my nameless impulses as they were. These two coexisted. While I could send out messages through our records or even through social media, I didn’t know how to face the madness and impulses inside me when I stopped playing live. That’s why I became unbalanced and couldn’t behave consistently.

But that can be a positive impact because, as I said before, I became aware once again of how important live performances are. That is partly why I decided to make the film (“i ai”). A film can lie as long as the work is set in a different time period. So if you say, “This is set 10 years ago,” you can have a live show and mosh. While the “Zen-Kankaku-Sai Festival” was not possible, I was saved by the nature of fantasy, which allows you to lie. When the COVID-19 pandemic started, I was really afraid that the world would become a place where we would never be able to perform live again, so I felt it was necessary to properly record the memories of that time. So perhaps one of the positive impacts the pandemic had on us was that we were able to make that film.

–It is true that in a fictional world, it is possible to have a live show. The reason why people couldn’t gather in the first place was, of course, to prevent the spread of infection, and because the live houses were closed, but also largely due to what sociologist Ryosuke Nishida calls the “infection of anxiety”. In other words, even if there was zero risk of infection, the gathering itself attracted criticism.

Mahito: Someone even tsked at me when I just got on the train with a guitar on my back (laughs). It was just like the structure of bullies at school: people set up some target of attack and direct their negative energy toward it. It is not because the bullied children have done something wrong, but even if they have done nothing in particular, the people are looking for such a structure itself. I feel that the very human society in which adults live has the same structure as bullying. That’s how live houses were the focus of attention during that period. But the communication at those live houses kept me alive, and I became more aware of that, so I was determined to catch up on it.

Also, at the start of the pandemic, many things happened, such as band members leaving the band and people close to me passing away. It was not only because of COVID-19, but the silence of that pandemic made me think about how I should deal with such losses. Fortunately, I am now in a job where I can leave something behind, so I feel that I must create something not only through music but also through various other means.

“In the first place, being distorted in the same way that reality is”

–In retrospect, the dawn of the 2020s actually began not with the pandemic, but with the bombing of Iran’s national hero, Commander Soleimani, by the U.S. military. At the time, there were even fears of World War III. Then the emergence of the pandemic, the global spread of BLM, the corruption-ridden Tokyo Olympics, the war between Ukraine and Russia, the shooting of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and so on, and the world situation has been changing at a dizzying pace. So-called alternative music can be said to be something that has been confronting the fragility of common sense and footholds in reality, which can crumble at any moment. How did you accept that reality when you actually entered a world where existing common sense did not prevail?

Mahito: I think we have no choice but to be messed up along with the social destabilization, and first of all, we need to be distorted as much as our society is in order to get in tune with it. The word “pure” has always been considered a virtue, but now I don’t think it is such a beautiful word anymore. For example, as soon as you say “pure Japanese,” the term “pure” becomes a word used in the context of discrimination. Being pure, unblemished, and spotless is not beautiful at all; in fact, there are many layers intertwined and woven together. When confronting such a complex thing, I felt that I had to be messed up as well, otherwise I would not be in tune with it. I don’t think that straight-forward expression is the right answer at all.

This may sound too abstract, but I think that “first of all, being distorted in the same way that reality is” is an absolute requirement for expression in this day and age. I think many people create their own world by symbolically combining various things in their minds, but that doesn’t seem right. We have to face reality somehow. At least I can say that to dye the world in one color with one strong light is some kind of violence now. There was a time when it was considered a virtue to say, “A man’s gotta focus on one thing and break through it.” We are no longer in the age of that kind of force or violence.

I like horses. So I sometimes study a lot about horses, and when they are in a herd, they always have a leader. But in a horse herd, the leader is not the one who is bigger and stronger, but the one who is the fastest. In other words, in the event of an attack by a predator or some other danger, the leader is the one who can escape first. So horse leaders are the opposite of someone like Donald Trump (laughs). As you mentioned earlier, many things are happening in rapid succession, and the world is so messed up that can even be described as an emergency situation. To have a leader who is the first to be properly frightened, properly confused, and able to escape in such a situation is the exact opposite of the masculine aesthetic of focusing on one thing and breaking through it by force. I think that kind of feeling is very important.

–You went through a number of such chaotic events after the release of the previous album KLUE. How did the idea of releasing a new album come about?

Mahito: The day after Carlos left, we already started having studio sessions with members of the prototype of Million Wish Collective. I believe that when we let go of something and it disappears, it is time to seize the next something to replace that loss. Of course, I was very sad. But at the same time, I knew that if I stepped forward and made a move, there would always be encounters waiting for me, so I was like, “Let’s take this opportunity to play a new instrument with all the members.” Then Taka found the bagpipes, I picked up the trumpet, and Roscar started beating the bicycle (laughs). The day after we announced that Carlos was leaving, we had already started practicing.

I personally think that encounters and partings are set up to be equal in number. Well, as a matter of course, everything that you have encountered will always end up saying goodbye to you in the end when you are gone. The number of one cannot be greater than the number of the other, so even if something big leaves you, you will always have another big encounter. That’s how I understand from my life experience so far. So while I was sad, I was ready to start preparing for the encounter. In that sense, I guess I was already thinking of making the next album the moment Carlos left.

–It is unusual to pick up bagpipes, even if you are starting a new instrument.

Mahito: Taka has a weird monster inside him. He’s been like that since we first met. Anyway, I think he was also motivated to move his body, sweat, and play something. But bagpipes sound very political when you listen to them carefully. They are played at festivals, and they are also played in military songs. I think he has picked up an amazing instrument. It’s also inevitable.

A record of imperfection that can never be perfect

— You teamed up with the voice ensemble Million Wish Collective and performed for the first time at the Fuji Rock Festival in 2021. Why did you decide to focus on the theme of “voice”?

Mahito: After the start of the pandemic, what has been seen as the worst thing to do was to gather with a large group of people and talk and sing in a loud voice. Our first performance as a group was the show on The Red Marquee stage at Fuji Rock Festival, and the stage was filled with those two prohibitions (laughs). But I think voices are really diverse. When I was a student, I was sometimes told that I had a strange voice, but I don’t think there is a good or bad voice at all, although there may be a voice that is generally seen as useful, convenient, or comfortable. Even if that is the case, I have lived my whole life with this voice, and it has carried all the burden of conveying something to someone else, so it would not be real if I cannot affirm this voice.

Recently, when you record a song, you correct the pitch and remove noise to make it sound beautiful. It is true that my voice is distorted in some ways, but that is the complexity of my voice itself, and I don’t think it is right to remove it on the basis of whether it is useful or not. Also, the photos are all retouched. When I see celebrities removing some moles and leaving others, I realize how strange the world has become. We don’t even know if what we are seeing is a photograph or a composite image anymore. Even on Instagram, there are so many photos that have been beautifully manipulated with apps.

The problem is that the kids who see the pictures―or it may be right to describe them rather as composite images―of beautiful models, look at themselves in the mirror and think, “How ugly I am.” Thus, there are various mechanisms in the system of capitalism to fuel people’s sense of inferiority, accelerate their desire to buy more cosmetics or spend more money on plastic surgery. The same thing happens in the world of singing and the sound of musical instruments. Even though they call themselves a band, many groups make music that is no different from electronic music. For example, when it comes to drums, the hitting sounds and the fluctuation of the rhythm are the traces of a human being playing the drums, and it is not enough to have the snare or bass drum sounds in the exact position that they are supposed to be on the score. But then you get a smooth guitar and bass, and a song that could be sung by a machine.

But the truth is that the distorted voice has traces of the person who vocalized it. That is why I wanted to affirm such voices, and I think this realization led to the Million Wish Collective. In the first place, the members of Million Wish were not chosen because they have good voices. When we actually sang together, there were times when I was surprised to hear that they could sing much better than I had expected. (laughs).

— You were able to create choruses by layering and looping recordings of multiple voices, as you did on the previous album, and some of the songs on this album stand out for their interesting use of that collage-like format. But you are saying that there focused on the diversity of voices more than anything, right?

Mahito: Yes, that’s right. I think it is something that could be called spirituality. The same can be said about photographic works, but I like works that have the smell of the times when they were taken inside them, and that will properly age and become a thing of the past. Many expressions aim for eternity, and many creators create their work with that eternity in mind in its various forms. But I would like to cherish how things become old. In recording sessions, I strive for perfection in both the vocals and the band’s sound, but I also value the imperfections that prevent me from achieving them, and that is what I like about my works. I think that is what it means to be involved with others in the first place. Of course, we make choices when we create an album, but I focused on how to encapsulate that kind of “atmosphere”, not as a document, but as fantasy.

So, when you listen to Anochi five or ten years from now, the voices and other elements recorded in the work will make you think, “Ah, that brings back memories.” Becoming old means becoming the past, but at the same time, such properly aged things can shine with a futuristic brilliance. I believe that time doesn’t just flow in one direction. This is even more true now, especially in the age of archives on the Internet. So I really enjoy how time is becoming more and more open in both directions. Conversely, I am not looking for something futuristic that no one has done before.

This interview continues in the second part

Photography Yuki Aizawa

Translation Shinichiro Sato

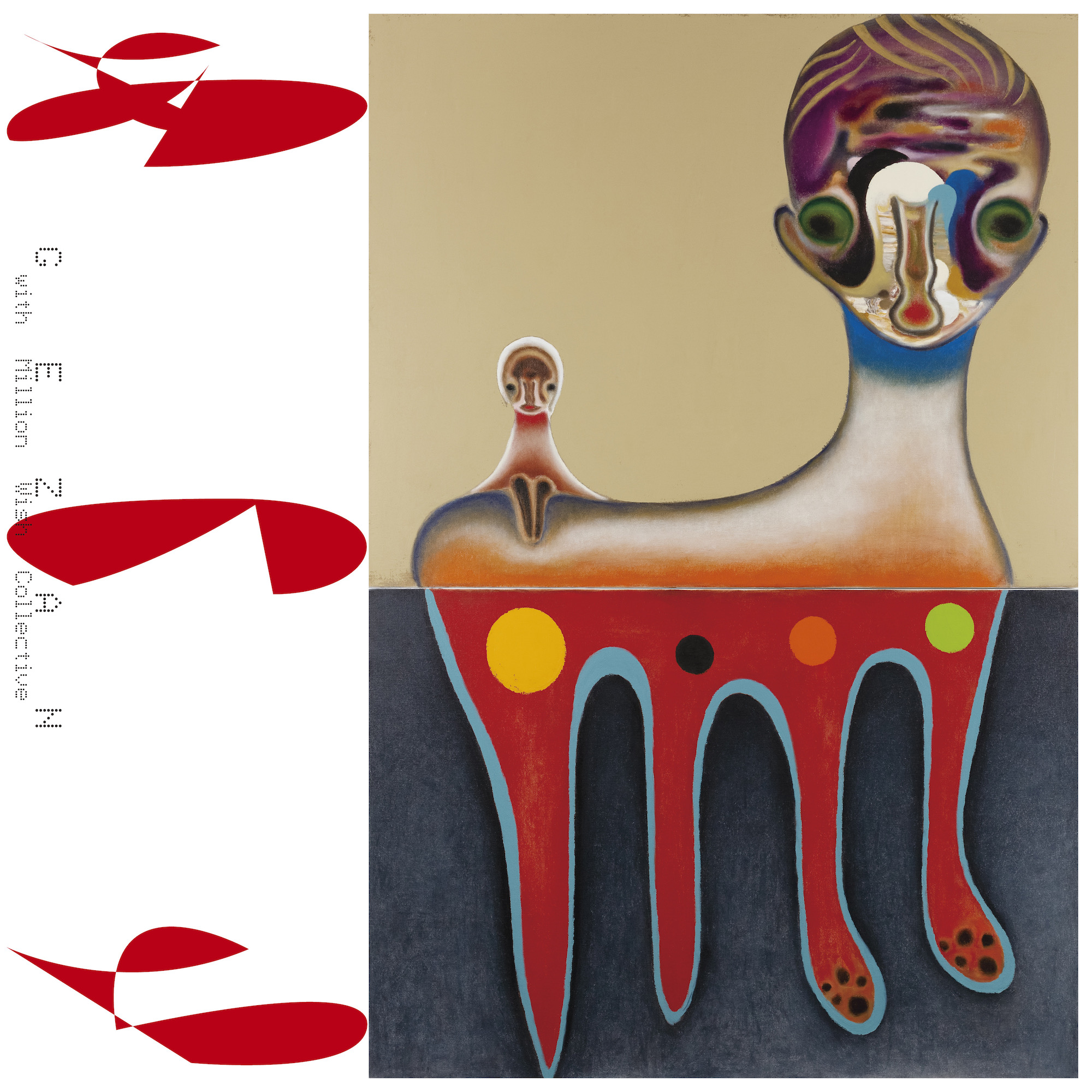

■ Anochi

Release date : February 1, 2023

Format : CD / Digital

Price : (CD) ¥3,300

TRACKLIST

1. A story before Life / (い)のちの一つ前のはなし

2. Chuken – Death Penalty Dog / 誅犬

3. Fight War Not Wars

4. We Can’t Take It Anymore / もう俺らは我慢できない

5. We All AFall

6. Tokyo Dub Story

7. SUITEN – INTERSECTION / 萃点

8. SORA TAPI WATASHI TAPI (bird talk) / そらたぴわたしたぴ(鳥話)

9. We Were The World

10. Third Summer of Love

11. Prelude to Finale Red caught Anochi’s eye / 終曲の前奏で赤と目があったあのち

12. JUST LOVE

13. Linda ReLinda / リンダリリンダ

https://gezan.lnk.to/ANOCHI

■Anochi release BODY LANGUAGE TOUR 2023

January 27, 2023 at WWW X, Shibuya, Tokyo

February 1, 2023 at Sound lab mole, Sapporo, Hokkaido

February 25, 2023 at FORCE, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka

March 2, 2023 at CLUB UPSET, Nagoya, Aichi

March 4, 2023 at UMEDA CLUB QUATTRO, Osaka

March 18, 2023 at LIVEHOUSE CB, Fukuoka

March 19, 2023 Hiroshima 4.14

March 21, 2023 at YEBISU YA PRO, Okayama

March 31, 2023 at F.A.D YOKOHAMA, Yokohama, Kanagawa WITH Soushi Sakiyama

April 2, 2023 at Saitama HEAVEN’S ROCK shintoshin VJ-3 / WITH Ohzora Kimishima trio

April 18, 2023 at Sunplaza Hall, Nakano, Tokyo

https://gezan.net/live/