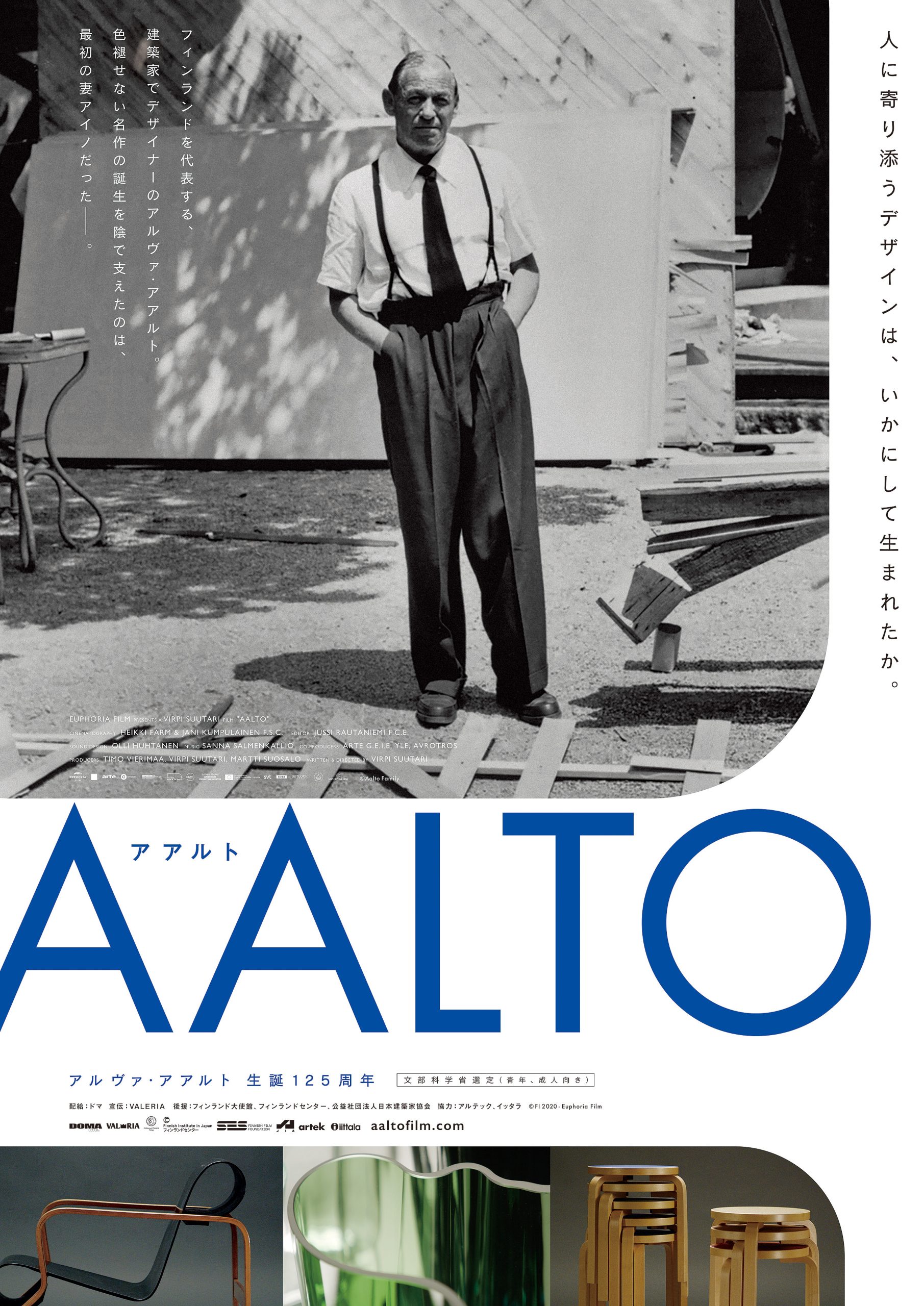

Aalto: Architect of Emotions, a documentary film about the distinguished late Finnish architect and designer Alvar Aalto, was released on October 13th, 2023, to commemorate the 125th anniversary of his birth. The film is a tapestry of beautiful moving images and music that shows the process of how Aalto gave shape to his ideas all over the world. Not only does it follow his life and body of work, but it illustrates the love story between Aalto and his first wife, fellow architect Aino, for the first time. In addition to rare family photos, archival footage, and testimonies from concerned parties, we get a window into the unknown side of the couple through their intimate letters. Upon her arrival in Japan before the film’s release, we spoke to the Finnish director, Virpi Suutari, about the insights behind making the film and her thoughts on Aalto’s work.

Virpi Suutari

Virpi Suutari was born in 1967. She is a film director and producer based in Helsinki, Finland. She is a member of the European Film Academy. Suutari’s film, Aalto: Architect of Emotions, won Best Music and Best Editing at the Jussi Awards, the Finnish equivalent of the Academy Awards.

Alvar Aalto

Alvar Aalto was born Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto in Kuortane, Finland in 1898. He was born to a land surveyor father and enrolled in Helsinki University of Technology in 1916. Aalto was born in a family of generational foresters and grew up loving trees since he was young. He established his own architecture office in 1923. In 1935, with his wife, Aino, he founded Artek to sell furniture, lamps, textiles, and more to the world. Aalto designed over 200 buildings in his lifetime, known for their masterful and superb combinations of organic shapes, materials, and light.

Aino Aalto

Aino Maria Marsio-Aalto was born in Helsinki. She enrolled at Helsinki University of Technology in 1913. She joined Aalto’s firm in 1924 and then later married Alvar. Her name became known after the release of her glass, Bolgeblick. She was Alvar’s private and public partner until she passed away in 1949.

A story based on the director’s adolescent experience with Alvar Aalto’s architecture

—―How did you first encounter Aalto’s architecture and works?

Virpi Suutari: Every Finnish person has encountered Aalto buildings, design objects, or furniture because we have so many Aalto buildings. Almost every Finnish family has some Aalto objects at home. We have Aalto kindergarten furniture, and in schools, we have furniture designed by Aino Aalto and other people from Artek. It’s part of our everyday life.

But what made me make this film was my childhood memories in my hometown, Rovaniemi, which is by the Arctic Circle in Lapland. It was destroyed and totally burned down in the Second World War, and in the 50s and 60s, Finnish architects, including Alvar Aalto, came to the rescue and started designing the city again. Aalto designed many magnificent monumental buildings for Rovaniemi, and one of them was the Aalto library, which I visited almost every day after school. The winters in Rovaniemi were harsh and cold—it would drop to minus 30 degrees. I used to go to the Aalto library because I needed a warm place, and it became a dear place for me. I loved everything about it: the shape of the main library hall, the leather chairs, and the beautiful glass lamps. I was also studying at the music school in the Aalto Theater, so I was in the Aalto buildings a lot, and those memories stayed with me.

I’ve been making documentary films for around 30 years, so I thought it was time to explore Alvar, Aino, as well as his second wife, Elissa Aalto, more carefully. I wanted to get to know them personally, but I also tried to understand why my experience in the library was so magnificent. What was so special about it? What was their architectural thinking? I wanted to understand that and share it with everyone else in Finland, Japan, and other countries.

――Alvar Aalto is such an iconic figure not only in Finland but internationally. Did you feel any pressure to make a documentary on him? How much time did you spend on the research?

Suutari: That’s a very good question because almost every Finnish person has an opinion on Aalto architecture. All the Finnish taxi drivers think they are the best critics of Aalto architecture (laughs). They’re critical but very proud at the same time. But then, there are Aalto Puritanists, who are these Aalto fans who think you shouldn’t say anything critical about Aalto.

Everyone has an opinion, but I knew that for my own view on Aalto, I needed to make my own film—a film that aesthetically came out of me—based on careful research. The core of the film had to be in my own childhood memories of my experience of the Aalto buildings. I knew there had to be this atmosphere of love, humor, and warmth. I knew that if I did my research well, I could do whatever I felt was the best with the material and be confident about it. That’s what I did. It was like the Aalto couple moved into my home for four years. I was constantly researching and thinking about them, so much so that I had dreams about them. In the end, my husband was tired of them. He is actually the voice of Alvar Aalto in this film because he’s an actor. When the film was finished, he told me very gently but firmly, “Maybe it’s time Alvar and Aino move out of our house and stay outside the gates of the house” (laughs). But now they’re in Japan, which I’m happy about.

――I was pleasantly surprised that this film is very human. It’s not just talking about their work. There are human relationships at the core of the film. Why did you decide to make a documentary with this kind of approach?

Suutari: I didn’t want to make an academic theoretical film. I wanted to do good research behind the film to ensure I didn’t make any mistakes, but I wanted to make a film anyone could enjoy. You don’t have to be an expert to see this film. Of course, you can be an architect to see it because I’m sure there are new things even for researchers and experts. But ordinary viewers can get so much out of it. I want to make films that can speak to anyone. Of course, I’m interested in the buildings, all the details, and beautiful objects, but I’m interested in human beings. That’s what I’m interested in as a documentarist.

It was important for me to look behind the scenes to figure out who Alvar Aalto and Aino Aalto were. Also, it was important to shed light on Aino Aalto’s role and her importance in creating Aalto architecture and design because she did most of the beautiful interiors we admire in the buildings they designed together. So, it was time to credit Aino and his second wife, Elissa.

“ But what touched me the most was Aino’s loneliness in her last years”

――It was interesting to learn about Alvar and Aino’s relationship, personalities, and how they collaborated through letters. What surprised you the most when you read those letters?

Suutari: I was surprised by how modern they were in their thinking. We tend to think people who lived 100 years ago were old-fashioned, but they were living in their own time. The Aalto couple especially wanted to be modern in every aspect of life. They were interested in new technology and broadening their ideas of sexuality, physical health, and things like that. That was a surprising element for me.

But what touched me the most was Aino’s loneliness in her last years. Alvar Aalto was a very outgoing extrovert. He had a wonderful, charming personality but was also quite self-centered. Sometimes, Aino Aalto handled being the CEO and artistic director of the Artek furniture company by herself. She had two teenage kids at home and was an architect, so she had a lot to handle. Aino was quite alone when Alvar Aalto worked at MIT in the United States. It was pretty touching to read those letters; she was constantly blaming herself for her feelings of loneliness and how she couldn’t think bigger like Alvar Aalto.

What also touched me about Alvar’s letters was his repeatedly craving and missing those first years they started working together. He always dreamt about that period when things were easier between them, and they were discovering new modernism together. He repeatedly wrote about craving to be back in that mental state of working together.

――The film features precious family photos and all kinds of family archives, and we get to see who they were as a couple. What did you discuss with the Aalto family in making this film? Did they give you a list of do’s and don’ts?

Suutari: It took a while to get their trust, but once I got it, I met Aalto’s other family and his grandson several times. With their trust in my project, they were open and didn’t give me any restrictions. Of course, I was in dialogue with them and would tell them what I’d do. But I was totally free to do whatever I wanted to do with the materials. I was very aware that some of the materials were delicate, like the drawings that Alvar Aalto did of Aino on her deathbed. You have to have a sensibility to use that sort of valuable material.

I’ll always remember the moment Aalto’s grandson came to my office. He opened his car, and there was this big brown box. We carried it to my office, and I started reading the letters that were in there. Then I told my assistant, “Okay, we’re making the film.” That material gave me the confidence to make a film that isn’t just about architecture but much more—about this timeless creativity between a beautiful couple.

――I read that Aalto was influenced by Japanese architecture in his projects such as Villa Mairea. When researching for this film, did you feel the influence that Aalto had from Japan?

Suutari: I think so, and people wiser than me have said there are Japanese influences in that house. For example, there is the winter garden, which reminds me of some Japanese features and spaces. They never visited Japan, but they certainly had some Japanese literature. At the time, in Stockholm, there was a famous Japanese tea house, and many architects were influenced by it. Researchers said Aalto probably visited that tea house as well and got ideas. Also, his use of wood: it’s like the forest has entered the interior. In the living room, there are these wooden pillars. So, there are some similarities to Japanese thinking, like how the interior and the exterior are in dialogue.

Villa Mairea is probably the most beautiful private house I’ve ever visited. I had the pleasure of staying there with my film crew and saw the house in different lights, like the morning light, and sitting by the fire in the evening. We also went swimming in the beautiful kidney-shaped pool and experienced all the luxuries. In those moments, you think, “Oh, what a wonderful profession it is to be a documentarist!” (laughs).

――In many documentaries, we see talking heads one after another and often get a very academic impression from them. But in this film, all the comments by experts were only in narration. It’s wonderful we get to be immersed in the whole world of Aalto along with the beautiful music.

Suutari: It was certainly our intention to make it like that. It’s challenging to make a film based on archives when the subjects are no longer here. The challenge was how to make the film fluid and organic and clean the dust away from the archive material. The soundscape, music, and editing had big roles in achieving that. It was a big, important choice to leave all the talking heads out and create one big narrator out of several narrators. It was more work for me to do it that way, but I think it made the film much more organic and beautiful, and the viewers could dive into the world of Aalto.

A film where the viewer can feel the beauty of the details, the Aalto couple’s forte

――After watching this film, I came to like Aalto more than before. Could you share with us if you have any personal favorite architecture or furniture that Aalto designed?

Suutari: Well, I’m sitting in the Artek store in Tokyo right now, and I’d like to have all the beautiful chairs and lamps from here (laughs). But I promised myself when I finished the film that I’d get myself a Paimio chair, and I did. It’s probably not the most comfortable chair to sit on, but it’s something I love every day when I look at it. It’s absolutely gorgeous. It’s like a sculpture, but you can sit on it too (laughs). This film process made me realize all the details because the Aaltos were masters in creating details in the buildings. All the door handles, handrails, and, of course, furniture and glassware were carefully thought through. The beauty relies on these details, and you get to see them more clearly after seeing the film.

――Is there anything you’d like to say to the Japanese Aalto fans and film enthusiasts looking forward to watching this film?

Suutari: I hope you check this film out because it gives you an enchanting, exceptional tour of the Aalto buildings worldwide. Not only can you see buildings in Finland, but you can also see ones in the United States and many European countries. If you can’t afford to go to those places immediately, it’s much cheaper to go to the cinema, buy a ticket, and be in those places. Also, you can dive into the beautiful love story of one of the greatest modernist couples, Alvar and Aino.

■Aalto: Architect of Emotions

Title: Aalto: Architect of Emotions

Director: Virpi Suutari

Year: 2020

Distribution: Doma

Advertising: Valeria

Supported by: The Embassy of Finland, Tokyo, Finnish Institute in Japan, Japan Institute of Architects

In association with: Artek, Iittala

2020/Finland/103 minutes/ (C) Aalto Family (C)FI 2020 – Euphoria Film

Official website: aaltofilm.com

Out in theaters nationwide on October 13th, 2023