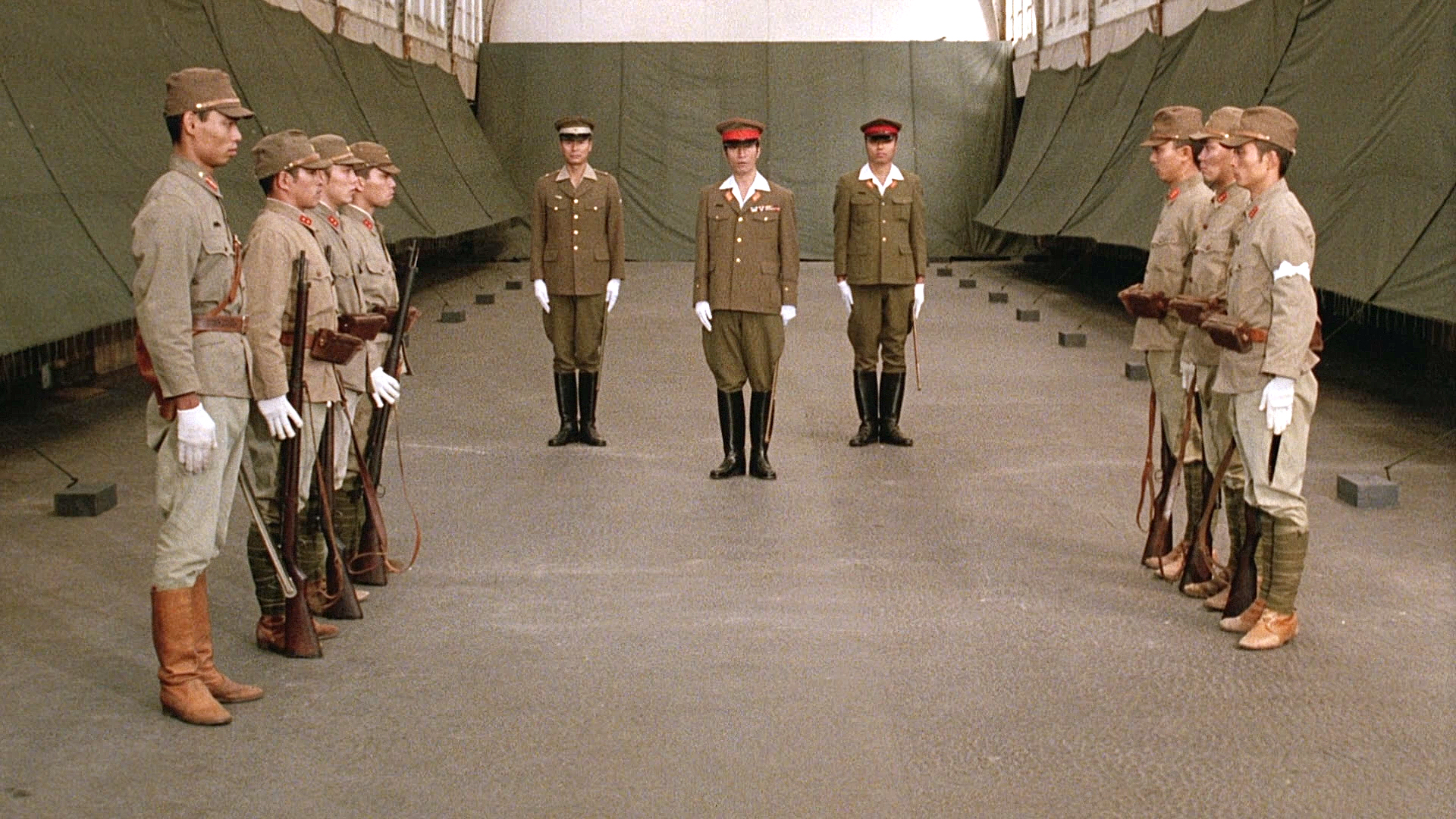

Before film director Nagisa Oshima’s works become nationally archived, the 4K restored versions of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence and In the Realm of the Senses are currently being shown in movie theaters all over the country. Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983) is based on the book, The Seed and the Sower by author Laurens van der Post. The story is set in a Japanese POW camp in Java, Indonesia, in 1942 during WWII; it looks deeply at how individuals exist amid the darkness of wartime violence and the place where life and death belong. Simultaneously, the film illustrates how the human spirit can be moved beyond the reality of the situation.

©Nagisa Oshima Productions

The Japanese soldiers, such as Yonoi and Hara, abide by the belief of protecting their god—the totality and order of the nation—and eradicating a sense of individuality without questioning whether it’s right or wrong. Hara’s words, “I’m ready to die,” echo this mentality. The Japanese soldiers’ distorted sense of discipline manifests in the devious ways they treat the prisoners of war.

In contrast, the foreign prisoners, such as Lawrence and Hicksley, adapt to their environment and live to fulfill their individuality based on modern values like social norms and rationality. Celliers appears beautiful, heroic, and charismatic, but his spirit is haunted by his “original sin,” in which he betrayed his younger brother and, in turn, himself. Through his interactions with Hara, Lawrence discerns the Japanese soldiers’ ancestral worship, views on life and death—a primitive aspect at the root of the soldiers’ mindsets—and the existence of the individual spirit.

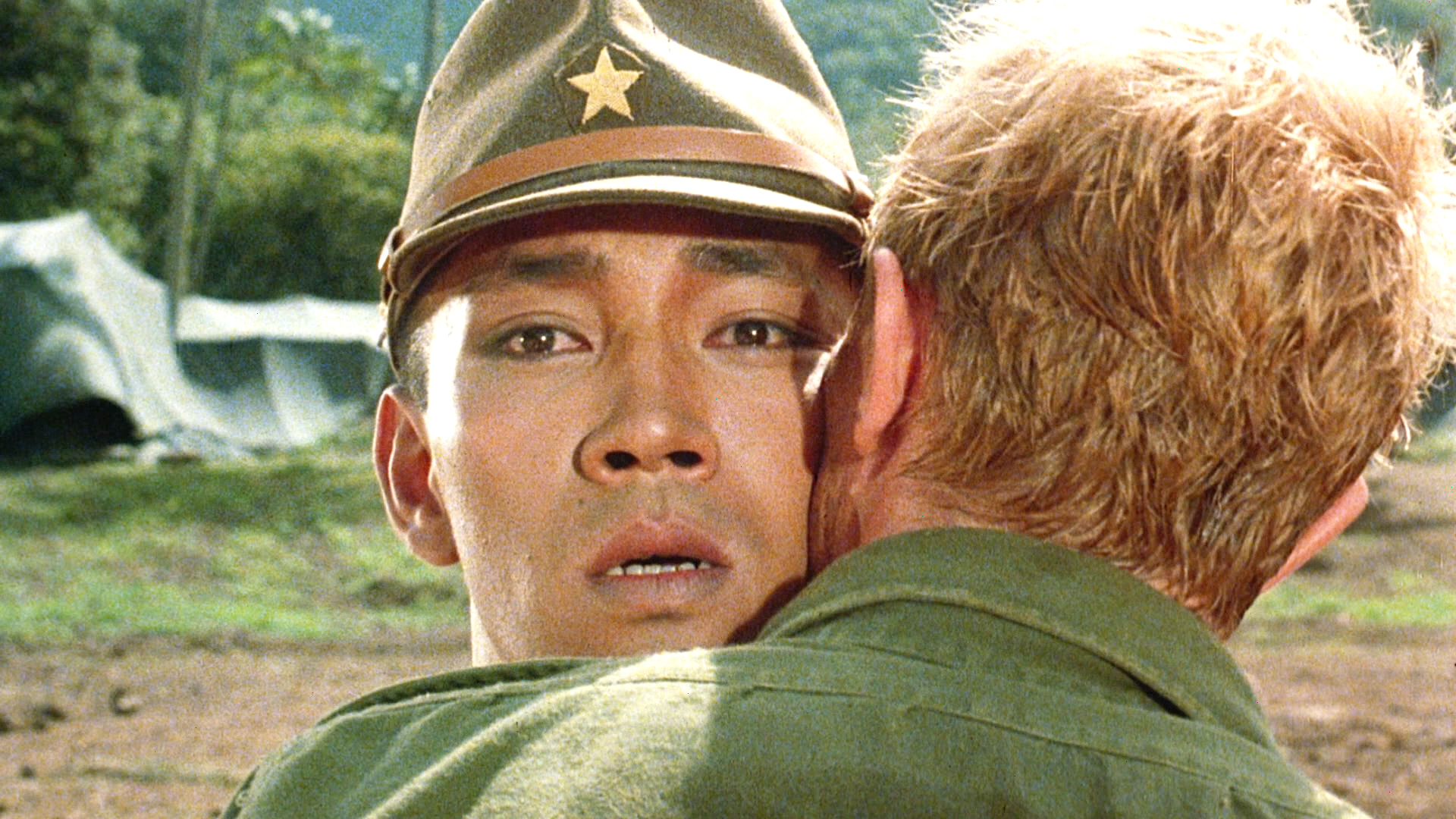

On Christmas night, the eve of Lawrence and Celliers’ scheduled execution, Hara pretends to be drunk, and playfully releases them, entrusting his individual intentions to the non-exist “Father Christmas,” the symbol of the festival. Although Yonoi scolds Hara for his actions, he gives him a cigarette in private, an imperial gift.

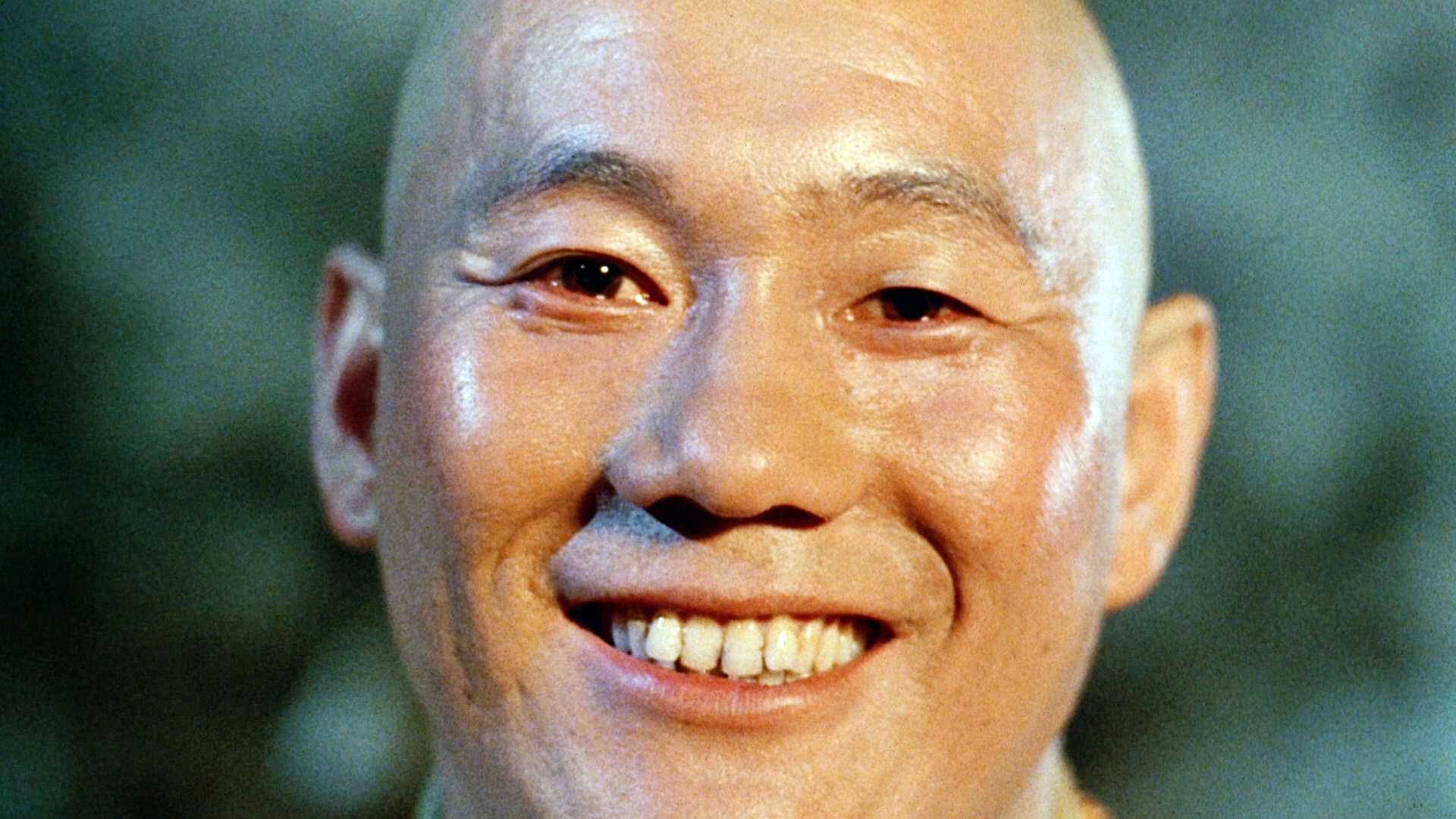

In exchange for his own life, Celliers frees Yonoi’s tortured soul, saves the prisoners, and sows a seed in the hearts of everyone. And once again before his final moments, Hara releases the tearful Lawrence and his own soul with the words that night “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” and a radiant smile.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence condenses the heart of human emotion and dramatically depicts the individual’s introspection on life and the seeds of forgiveness and salvation that get passed from one person to the next, which is written about in the original book in detail. We spoke to Naofumi Higuchi, film director and the leading expert on Nagisa Oshima, about the film’s background and appeal.

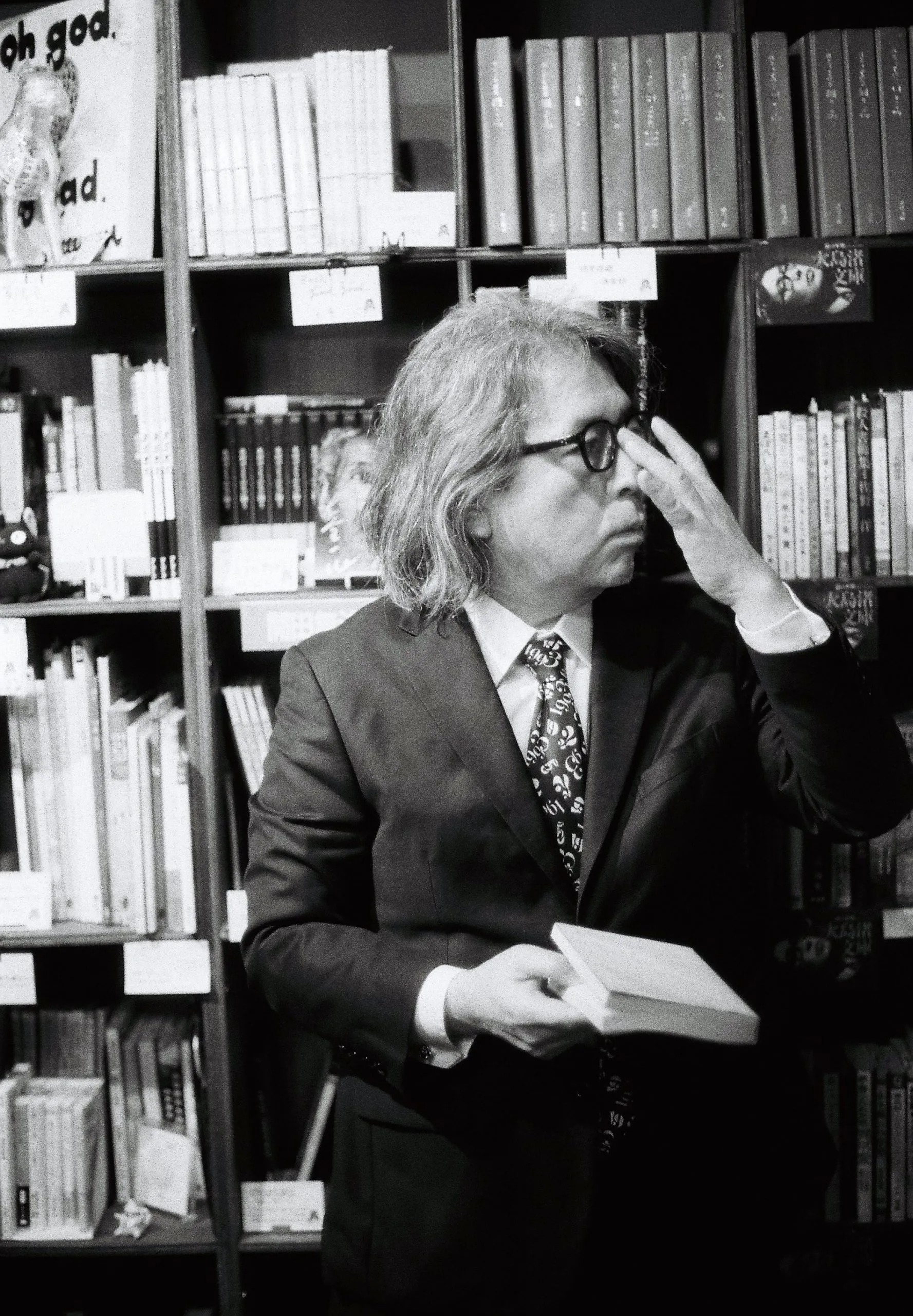

Naofumi Higuchi

Naofumi Higuchi is a film director and critic born in 1962. His book, Oshima Nagisa Zeneiga Hizou Shiryoshusei (Kokushokankokai), got first place in the Kinema Junpo Award 2021 for Best Film Book. Other notable books include Oshima Nagisa no Subete, Kurosawa Akira no Eigajutsu, Jisoji Akio Saiki no Garan, Akiyoshi Kumiko Chosho, Romanporno to Jitsuroku Yakuza Eiga, Suna no Utsuwa to Nippon Chinbotsu 70nendai Nihon no Chotaisakueiga, Showa no Koyaku Mou Hitorino Nihoneigashi, Good Morning, Godzilla Kantoku Honda Ishiro to Satsueijo no Jidai, and more. Higuchi has directed Intermission and The Master of Funerals. He also operates “Neko no Hondana,” a shared bookstore in Jimbocho where shelves by movie people such as “Nagisa Oshima library” and “Shinji Aoyama library “ are collected.

Photography cooperation “Neko no Hondana“

Achieving both radicalism and popularity through Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

— Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence deals with profound issues at its core. Simultaneously, each actor’s individuality shines, and the soundtrack has become a timeless masterpiece. Among Oshima’s films, this has especially garnered a wide range of fans. What makes this film unique?

Naofumi Higuchi(Higuchi): Nagisa Oshima is a director that’s perceived differently according to the generation. During the golden era of filmmaking, the 1950s, he graduated with a degree in law from Kyoto University and joined Shochiku, the most conservative Japanese film production company, where he made films that broke the formula of traditional Japanese filmmaking with his subject matters and methods. By the 60s, he founded Souzousha, an independent film production company. Oshima’s unconventional works were embraced during the student protests and campaigns against the Japan-US Security Treaty, an era of upheaval and searching. As an innovative, leading figure, he was popular among the youth at the time. The director’s original fans looked up to him as a lone, antiauthoritarian champion, but he had the selfish desire to be both popular and radically fierce.

Oshima had a persistent intent to show the people something radical in the form of something popular since the beginning of his film career. The postwar Japanese left didn’t gain popularity, was at an impasse, and eventually crumbled. Perhaps, fundamentally, he felt there was no point in appealing to oneself [as opposed to appealing to the masses]. For instance, he cast superstar singer Harry Belafonte as the Black airman in his socialist film, The Catch (1961), based on a book by Kenzaburo Oe, and for Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1968), he cast underground icons like Tadanori Yokoo and Juro Kara. His works were very artistic, but he loaded them with journalistic codes so people would talk about them more.

Two decades later, Oshima stuck to his intent and got the opportunity to create Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence with the international market and film festivals in mind. At first, he made a film proposal for a conventional literary epic with respected, famous domestic and foreign actors so that he could jump on the Japanese blockbuster bandwagon. However, Oshima couldn’t cast said actors because of differing ideas and schedules, so he cast Ryuichi Sakamoto and Takeshi Kitano at the last minute. Oshima didn’t know of Sakamoto initially, but he acutely understood people’s stage presence. This casting choice became one of the primary factors that gave the film exceptional artistry and mass appeal.

The popularity that Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence gained is one of the director’s achievements, considering his wish to reach an audience. Until then, people had this image that Oshima made arthouse films that were solemnly shown in small movie theaters. But the casting of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence was so strong that it was decided it would be shown in big movie theaters that previously showed box office hits from abroad like E.T., despite the film’s artistic content. Some of his original fans criticized the film, saying the casting choice was a deliberate ploy to get attention, but young people responded with fervor. The director especially got a lot of support from young women. At the movie premiere of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Oshima ran onto the stage like a Japanese idol to greet the audience of young women cheering, wearing a shirt by Kansai Yamamoto that said “THE OSHIMA GANG” with a bandanna on (laughs).

Film critics said Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence was a film portraying Western and Eastern cultures as opposite ends, but Oshima rejected the idea, saying he didn’t make such a thing. He hastily explained that he depicted people being drawn to each other, using a critical choice of words. Even if people are bound by various obligations, burdens, pride, certain encounters, and many other hardships, people will always irrationally be attracted to others, even if it doesn’t come to fruition.

On the contrary, rather than perceiving the film as obtuse, the young women fans recognized the simple, true nature of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, despite the film being many of their first introduction to the director. The letters they sent him arduously detailed their observations. Oshima felt that they truly understood what the film was about and preserved the letters with great care. He replied to some of them too. Oshima and the women fans were in sync with each other in their haste and urgency to get to the heart of the matter without reason or pretense, embodied by his pesky, original fans. To this extent, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence could be seen as the materialization of Oshima’s ideal—the coexistence of radicalism and popularity.

An authentic presence, a baroque balance that has no predictable harmony

–I believe Ryuichi Sakamoto and Takeshi Kitano delivered memorable performances because they didn’t have any acting experience and were able to reflect the impression they got from the scenes and the original book. How was Oshima able to create a complete film with non-actors?

Higuchi: Oshima thought it was boring to only work with people that strictly followed his orders. He didn’t ask the actors to deliver a technical performance; he wanted them to show him something unpredictable. Even if the inexperienced cast showed apprehension on set, Oshima told them there was nothing to worry about because he valued their command of presence, not their technical skills. He had faith in the cast. Being on the receiving end of that trust entails a lot of responsibility, and giving that trust as a director is an act that requires courage. That’s why the actors in his works deliver fresh, momentous performances only made possible with the exhilaration of leaving things up to chance.

The true essence of acting in films doesn’t lie in the technique but in the actor’s presence: this was Oshima’s pet theory. He mentioned that his order of priority in casting was 1: amateur, 2: singer—he didn’t have 3 or 4—and 5: movie star. His best masterpiece with a starring amateur is probably Boy (1969). He visited an orphanage in Meguro in search of a boy to play the protagonist and selected a real orphan to play the part, thus depicting an authentic presence.

Further, for the most part, Oshima only shot one or two takes per cut, which would surprise many seasoned actors, but this way, he was able to capture the raw quality of non-actors. David Bowie gives a remarkable performance through his own interpretation of his character in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and I bet Oshima was delighted to witness his eccentric ways.

As a whole, the structure of the film is somewhat awkward. It has a sort of baroque imbalance, as if Oshima shot intricate scenes with momentum and quickly put them together. Take the scene where Lawrence and Celliers talk to each other over a wall in their separate cells. Lawrence recalls his past in short sentences, while Celliers’ recollection is told through elaborate visuals. Visually speaking, there’s a clear imbalance here. Oshima had shot the only scene that included a woman, which was Lawrence’s recollection, but it all got cut. This resulted from Oshima’s sensibility, as he believed the film would be stronger if it only had men, even if that meant it would lack balance.

By using the cast, location, issues during the shoot, accidents, and changes to his advantage, Oshima completed Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence as something unpredictably brilliant. The filmmaking process parallels the story, in which people clash awkwardly and eventually develop a rapport.

The music and art that perfects the worldbuilding of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

—I get the impression that although the film is set in Java during wartime, the film’s location feels like it doesn’t exist anywhere in the world thanks to Ryuichi Sakamoto’s enigmatic score and the conceptual set design by art director Shigemasa Toda. I feel like Oshima was able to create a sort of utopia, which was what he wanted to develop through the film, because of the music and art department.

Higuchi: Oshima first asked David Bowie to create the soundtrack of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, which is now a part of film music history, but he said no because he wanted to devote himself to his role. The film score was born because Sakamoto voluntarily asked if he could make it. Oshima didn’t instruct or direct the musician but instead anticipated what his creativity and unpredictability could create. The director was the polar opposite of directors like Akira Kurosawa, who had a complete vision in mind and gave meticulous instructions.

Shigemasa Toda, the art director, had a distinctly singular aesthetic that people couldn’t process in an easy-to-understand way. So, most critics of his time didn’t recognize his true genius. That sense of restlessness in Oshima’s films is largely thanks to Toda’s art direction. There’s an anecdote: in Masaki Kobayashi’s film, Kwaidan (1964), it cost a massive amount of money to build the set, which was bursting with Toda’s strong point of view. Ultimately, the production company went bust because of that. After hearing this rumor, Oshima decided to meet Toda. He wondered what sort of weird person would come, but Toda was quiet and polite, to his surprise. It made him think, “Wow, this is the madman” (laughs). That’s how Oshima was drawn to him. Oshima’s works were very artistic, so he often had a modest budget, but Toda was so talented that he only needed a little money to demonstrate his vision. For instance, he would place something that shouldn’t belong in the scenery. He could change the film’s world, like flower arrangements, by making the set come alive. There’s no art director like him.

When you look closely, the film has a strange aesthetic, but Toda didn’t embellish it for the sake of being strange; he derived the visuals from the essence of the film, so it all surprisingly works well. The most specific example is the main POW camp set. We, as the audience, treat it like it’s normal, but no POW camp looks like that. The set, made out of timber, concrete, and tents, is basically like a greenhouse made out of glass. In the original book, The Seed and the Sower, the camp is where seeds of peace get sown and nurtured in the hearts of people on opposing sides. In other words, it functions like a greenhouse. POW camps don’t look like that, but when David Bowie, Sakamoto, and Peter Barakan, who tagged along, visited the location to see the finished set, they didn’t think it was odd-looking because Toda understood the essence of the story.

The significance behind showing a film that focuses on the true nature of humans today

–Young people today could have the opportunity to discover Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, now that it’s in theaters in 4K.

Higuchi: I feel like the themes Oshima put into Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, like “people get attracted to other people,” “the difficulty of obtaining true freedom,” and such, could be more easily understood today, which people call “the era of division and disparity” than when the film was first released. I especially think the young generation, whose awareness of LGBTQ+ people and issues is standard, will clearly and instantly understand the heart of this film, much like the young women who loved the film back in the day. Forty years after Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence’s first release, you can see how the young audiences that fill the seats in movie theaters feel genuinely moved. The times have finally caught up with this film.

■Merry Christmas Mr.Lawrence 4K restored version

Website: unpfilm.com/senmeri2023

©Nagisa Oshima Production

Direction Akio Kunisawa

Photography Hiroto Nagasawa

Translation Lena Grace Suda