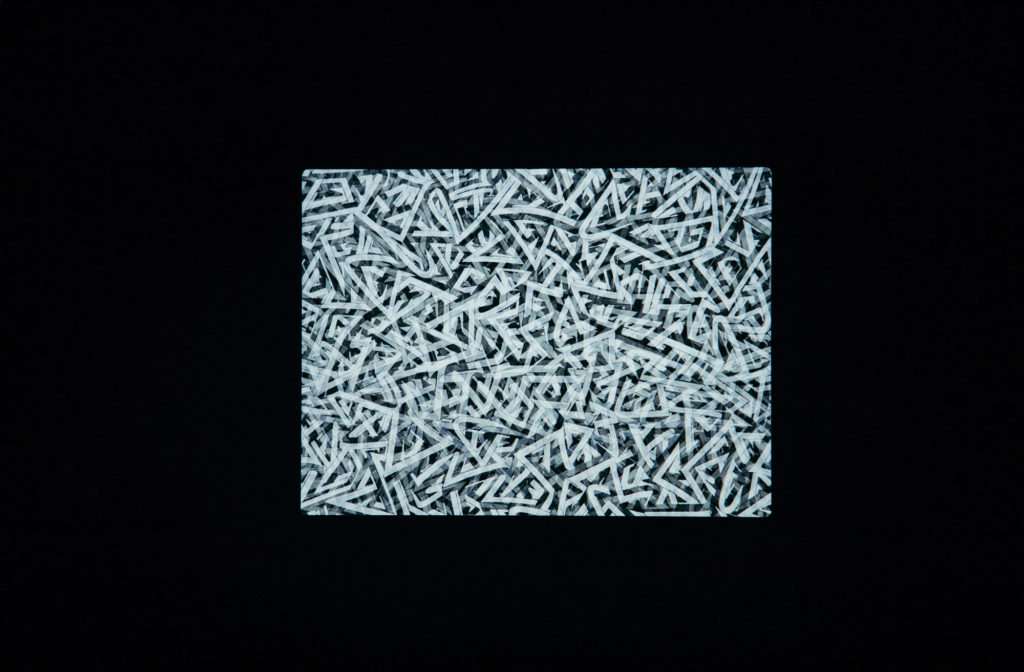

Shaped like illegible letters, the “Quick Turn Structure,” or QTS, a motif that repeatedly appears in New York-based artist Enrico Isamu Oyama’s impactful art, active since the early 2010s, bears symbol-like features, as well as a unique sense of mystery. Anyone who stumbles upon Oyama’s work ends up asking themselves: are these letters, or shapes? Is it something to read, or some kind of rhythmical pattern?

This motif finds its roots in aerosol writing, a subculture in which Oyama has been interested since his high school days. Focusing on QTS, he has been expanding his art through paintings, three-dimensional figures, sounds and installations, analyzing the history and trends of aerosol writing, as well as the physical sensations and thoughts related to his act of drawing. In 2011, he collaborated with Comme des Garcons to decorate the collection with his artwork.

Redrawing the line connecting street art and contemporary art

-I heard that your interest in aerosol writing started in high school. Were you actually writing on the streets at the time?

Oyama: I did a little when I was in high school, but I can count the times on one hand. I was not a street writer. If anything, I would write on a piece of paper and show it to others. However, at the time, there was a strong tendency in the community of street culture to think that those who weren’t writing in the streets were not real writers but fake and unconvincing, and there was a time when I was struggling with my artistic identity because of that. I was feeling that I failed to be a real writer. Though, it is true that aerosol writing influenced my drawing. That fact is a reality, not a made up. So, with that as a starting point, I decided to digest this influence and reinvent my own artistic idiom and share it with the world. In this way, I concieved the motif “Quick Turn Structure” and conceptualized it as my iconic expression. Currently, I’m reinterpreting street art to my extent, with a particular focus on visual language, and presenting them in the field of contemporary art. By clarifying the distance between myself and the street culture, I’m clarifying where I stand and what I want to convey.

-You’re also doing a study on street art; specifically, what are you researching?

Oyama: Street art means a lot of things and includes different type of artists and works. Banksy is street art, but not aerosol writer anymore. In my case, I’m interested in a particular type of street art called aerosol writing, especially the one which developed in New York around the 70s and 80s. However, I’m not specialized in that field as a researcher, but rather as an artist; I’m absorbing as much as I can of it.

-Talking about that era, what interests you the most?

Oyama: Aerosol writing has its roots in the early 70s in New York; it blossomed in the 80s and, since the mid-80’s and 90s, it has evolved in different places and ways interntionally. New York in the 70s and 80s was an energetic place filled with the important seed of street culture. For example, just as Jimi Hendrix developed and expanded the potential of the electric guitar, aerosol paint pushed the potential of street art to the next level in that era. It’s exceptionally fascinating how everyone started painting on subway cars; it’s like an artistic medium that goes across town. Many of the writers of the time were very young, so their range of daily activity was limited, and that’s why, through the subway system, they devised a method to show their existence in the form of art to the public who lived further away from them. The aerosol writing of the time in New York was impressive in terms of design too. New York, where abstract expressionism was born in the late 40s, became an important location for the art scene, forming an intimate relationship with the concept of abstraction, which is why some of the aerosol writers in the 70s and 80s also had tendency towards abstraction. Banksy and other artists in the Europe conveyed their message of social criticism and satire through concrete illustrations; New York artists such as Futura 2000 and Rammellzee, for example, focused on abstraction through letter forms and created their own original universe. There was a lot of potential for expression in aerosol writing in that era, from their visual aspect to the way they “hacked” the city like urban guerrilla.

The reason for using the term “writing” instead of “graffiti”

-In recent years, you’ve been using the term “aerosol writing” instead of the relatively generalized “graffiti.”

Oyama: One of the reasons was that I personally met and talked to one of the pioneers of aerosol writing, the New York artist PHASE2, who passed away in 2019. He didn’t appear in the media in his later years, but he always hated the word “graffiti” and was persistent in calling this culture “writing.” In Japanese, graffiti becomes “rakugaki,” meaning scribble, which has a negative nuance, hinting at illegal, troublesome behavior. Not only PHASE2 but also other pioneer writers of the early 70’s would call their expression “writing.” However, around the same time, the adults and the media started defining it as troublesome behavior, hence the term “graffiti.” So, in a sense, the word “graffiti” came from the prejudice and bias of the people outside this culture.

-Nowadays, some writers actively use the term graffiti.

Oyama: Some of the writers of the next generation say that what they’re doing is graffiti, an attack on society; vandalism with a rebellious spirit. Every culture and expression changes slowly over time. There was indeed a time when the essence of street art was illegal and rebellious, and such aspects are still there, but it’s fine for them to change; not all artists are like that. I myself wasn’t writing on the streets, and I’m involved in writing from a different angle, and if vandalism were at the sole core of this culture, I think it wouldn’t have spread all over the world this much. It is actually more complicated, or became complicated and diverse over time and we can not summerize it in one essential element. I personally see one of the most important appeals of this culture is straightforward self-expression through writing one’s name, which even a child can do. Sensibility or curisosity of a child is common among different languaghe spheres, social classes or ethnic groups worldwide, and I think that’s why writing spread universally. Reinterpreting this culture from the perspective of “writing” rather than vandalism is where I stand, and the message I want to convey with my art. In that sense, I am using the term aerosol writing.

-In your art, one can see important elements of modern and contemporary painting such as “abstraction,” “movement” and “repetition.” There are also techniques of modern painting that sort of “erase” the picture, instead of “drawing” it. Are you consciously introducing elements of the so-called fine art in your production?

Oyama: I wouldn’t say consciously, but rather spontaneously; I look at contemporary and modern art paintings, and I have many favorite painters. For example, Christopher Wool. First, he draws a line on a smooth surface support base with aerosol paint and wipes it, leaving a trace which becomes the painting. I also associate these kinds of works to Futura 2000’s. Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning is also deeply fascinating. Rauschenberg was a post-war American artist. He erased a drawing he got from Willem de Kooning with an eraser and presented it as his own work. On the streets, you can often see writings that were later erased with a roller, leaving slightly different color on the concrete wall; I see a sort of connection between that and Erased de Kooning.

Solo exhibition Noctilucent Cloud, showing new concepts such as spacing compositions inspired by stone gardens and ink espressions

-I heard that you went and researched different zen temples in Kamakura and Kyoto for this exhibition. Could you tell us about any creative input you got from that experience?

Oyama: The idea to visit temples came from Mr. Hitoshi Nakano, the curator of this exhibition. I’ve been based in New York for eight years now, and I’ve been somewhat thinking about my Japanese heritage and how to naturally reflect that in my practice: that’s why I went with him. Zen and Buddhism are profound cultures, though; it’s impossible to understand them with just one visit, so I just went there to find some inspiration.

-Specifically, what kind of inspiration did you get?

Oyama: I was particularly inspired by rock gardens. When placing stones in a rock garden, you’re practicing how to form space with the minimum amount of elements. If you identify the appropriate points, the space will fill with the relationship with each placed stone. In particular, the stone garden at Ryoan-ji Temple was the most unassertive, hard to describe: it was just there, and I was captivated by that. That’s not specifically reflected in this exhibition, but in Exhibition Room 5, the largest one with 700 square meters, I aimed to create an appropriate spatial relationship by limiting the number of exhibited pieces to six, which is very few considering the size of the space.

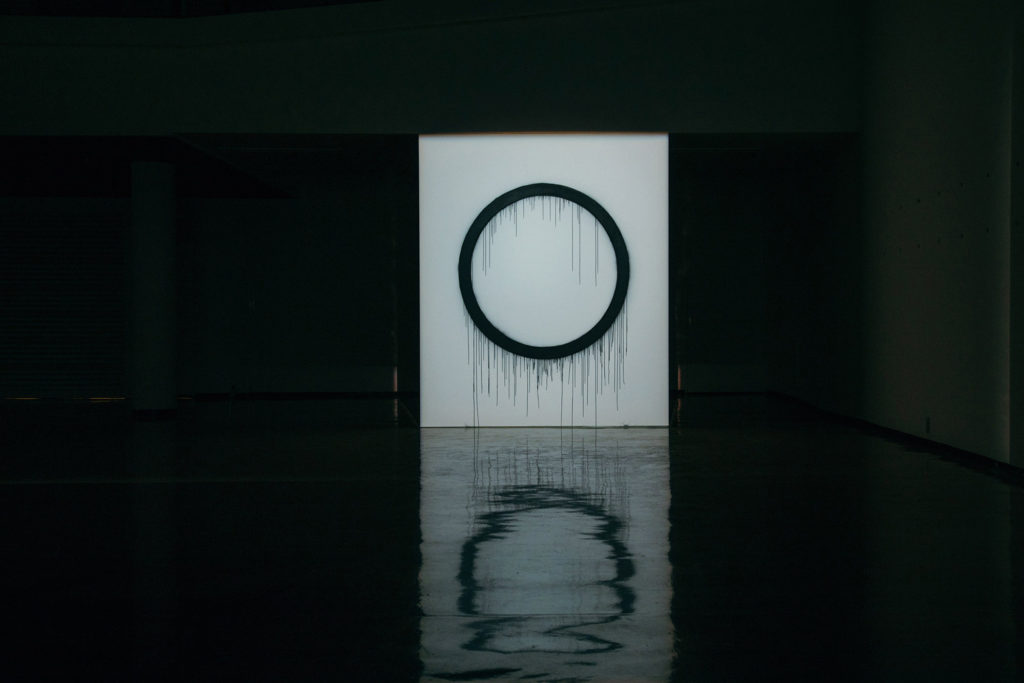

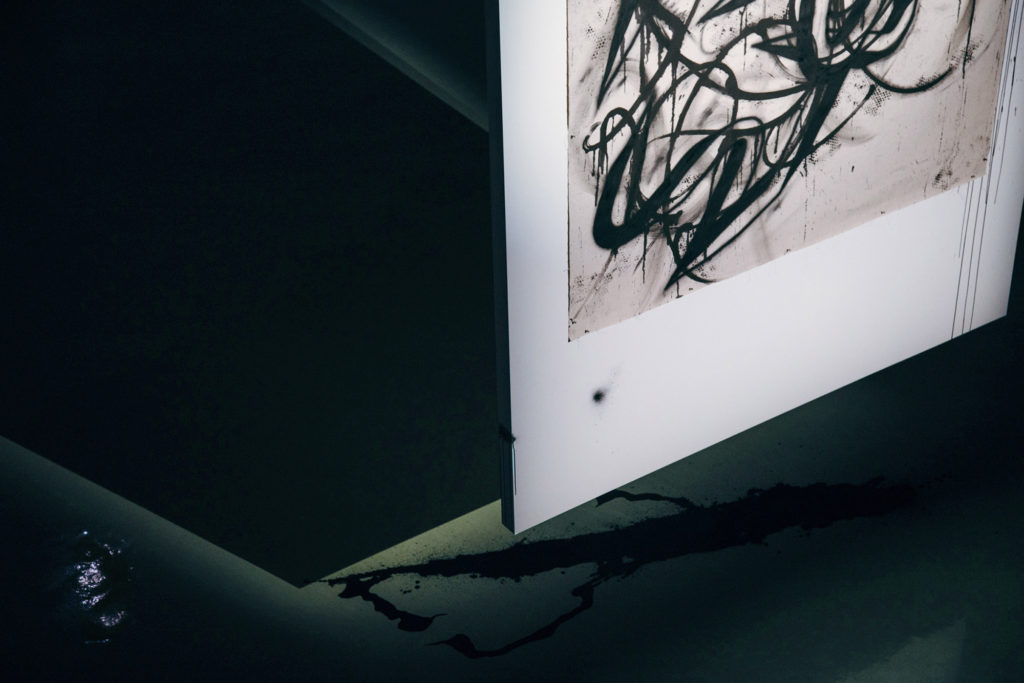

-In that exhibition room, there is ink drooping on the floor where the pieces are hung, to make the viewers feel some kind of presence is there. Is that kind of spatial practice like some sort of extension of writing?

Oyama: It’s about showing the paintings as an installation, which includes how to arrange and display the pieces. Even in my studio, it’s common for aerosol paint to droop on the floor. This installation is an extension of that feeling. In the Exhibition Room 5, some pieces made with aerosol paint and ink are showcased. Sho (Japanese calligraphy) is also another kind of writing. At first glance, Sho and New York writing may seem completely different expression, but they have something in common: they both pursue artistic formation letter shapes. This production is also based on that.

-The new three-dimensional piece Cross Section / Noctilucent Cloud is also on display. Can you interpret it for us?

Oyama: For this piece, I used a heat-insulating material called “styrofoam,” which is used in construction for buildings. I piled up about 200 plank-shape styrofoams whose thickness is 1.5 centimeters so it becomes about 3 meters high and cut off one side of it with a heat cutter. The physical sensation of cutting it is similar to that dynamic feeling of swinging my arm to draw a long line when I do live painting. It’s the feeling of giving a shape by roughly cutting through a large accumulation of styrofoam. You could say that this piece acts as a wide brush stroke with three-dimensionality in the space of the room. That and, styrofoam is originally light blue. I colored it black, but I slightly left the original color in some parts. If you look closely at the details of this black lump, you can see hints of light blue leaking from it. It reflects the image of this exhibition, the Noctilucent Cloud, glowing pale in the night sky.

-Although it looks very solid, it somehow looks light too.

Oyama: Styrofoam is a voluminous yet light material. There’s a piece by Jeff Koons which is a balloon-like sculpture made with solid metal. One of the interesting aspects of contemporary art is emphasizing the gap between how a piece looks and what’s it made of. The lightness of our postmodern society, sense of temporaly construction, and the way street art as signs floats and circulates in the urban space; those are some of the inspirations why I used styrofoam.

The act of redrawing lines creates new expressions and cultures

-The collaboration with composer and pianist Toshi Ichiyanagi during is one of the highlights of the exhibition, in my opinion.

Oyama: Mr. Toshi Ichiyanagi is the artistic director of the Kanagawa Arts Foundation, which hosts the exhibition. A project to commemorate the 20th anniversary of its inauguration is underway. Mr. Ichiyanagi was once active in New York, just like me. The keys of a piano, the music scores; they’re black and white, like my artworks. On the day of the event, a young pianist will perform Mr. Ichiyanagi’s compositions in the exhibition space.

-2020 was a year full of events that shook our social values, such as the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. Last year, you published your exchange of letters with Mr. Tetsuo Kogawa entitled The Semantics of Aerosol: Thoughts and Arts after the Pandemic – A Dialogue with Tetsuo Kogawa; could you tell us about the post-pandemic mindset we should all adopt?

Oyama: The pandemic is still ongoing, and it’s hard to say anything conclusive about it, however, we could at least say that our post-corona values and perspectives are different from how they were in pre-corona. For example, the word hikikomori used to have a negative connotation, but after the virus, remote work is recommended, and we could say that hikikomori-like lifestyles are at the forefront of our era. What we’re doing is the same, but its value changes depending on how you draw the line between positive / negative, encouraged / discouraged. It is about changing context and I think this may also happen in different scenes, for instsnce, art / non art. I’ve started doing my practice since there was a deep gap between street culture and contemporary art. In recent years, street culture’s way of expression has stepped over the boundary line of fine art, and that’s why it’s now acclaimed in that field too, but the line drawn between them hasn’t essentially changed. I think what’s happening is some type of street art or artists are just picked up by and integrated into comtemporary art keeping the border between the two realms. Instead, I think that by redrawing the fixed lines, by changing and shifting the boundary line, the values and perspectives of the world can change dramatically, and new expressions and cultures can be born.

Enrico Isamu Oyama

Born in Tokyo, 1983. In 2007, he graduated from the Faculty of Environment and Information Studies of Keio University and completed his Master of Fine Arts at the Department of Intermedia Art, Graduate School of Fine Arts at Tokyo University of the Arts in 2009. Starting from his unique motif “Quick Turn Structure,” that reinterprets the visuals of aerosol writing, Oyama is developing his art into different expressions such as painting, three-dimensional objects, spaces and media. He recently published The Semantics of Aerosol: Thoughts and Arts after the Pandemic – A Dialogue with Tetsuo Kogawa (Seidosha).

Website: http://www.enricoisamuoyama.net

Twitter: @enrico_i_oyama

Instagram: @enricoisamuoyama

Enrico Isamu Oyama – Noctilucent Cloud

Dates: December 14, 2020 – January 23, 2021

Venue: Kanagawa Prefectural Gallery

Address: 3-1 Yamashita-chō, Naka-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa-ken

Time: 11:00-18:00 (admission is permitted until 30 minutes before closing)

Closed day: January 7, 2021

Entrance fee: 800 Yen for adults, 500 Yen for students and people over 65; Free for high school students and younger

A collaboration event with composer and pianist Toshi Ichiyanagi will be held on Sunday, January 17th.

URL:https://yakouun.net/

Photography Ryosuke Kikuchi

Translation Leandro Di Rosa