Shigego Kubota’s retrospective exhibition is currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. Viva Video! The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota is an exhibition traveling in Japan through February 2022. This is the first large-scale solo exhibition of her works since her death, and the first to be held in Japan in about 30 years. In addition to the video sculptures and films works that represent Kubota’s artistic practice, the exhibition features drawings and documents that have never been publicly shown, presenting a comprehensive and multifaceted view of her creative activities from her early days to her later years.

New York-based contemporary artist and art critic Mark Bloch unravels the background of Kubota’s activities, which continue to generate a substantial impact on artists around the world, exploring what she had been thinking through and how she had been pursuing her own form of expression.

Encounters with Yoko Ono, Mieko Shiomi, and other artists

For Shigeko Kubota, recognition and internationalism were birthrights. She was born in 1937 in Niigata to a cultural family. Her grandfather was a painter in the Nanga style, 17th and 18th century Japanese painting that revered Chinese culture, with adherents that considered themselves literati. Both parents were teachers, raising her within a Buddhist culture, with an avant garde dancer for an aunt, leading her to collaboration with three post-war avant-garde movements: Hi Red Center, and Group Ongaku, started by two sound experimentalists with important roles to play for her: Mieko Shiomi and Takehisa Kosugi, and others. When Kubota met John Cage at Tokyo Bunka Hall in Ueno during a 1962 tour, Yoko Ono was a dancer in his troupe, back for two years from New York, fresh off the birth of Fluxus. Shiomi performed at Sogetsu Art Center as did Ono, her husband Toshi Ichiyanagi and Nam June Paik, Korean musician and Kubota’s life partner-to-be. Then, during Naiqua Gallery’s one year run in Shinbashi, Tokyo, Kubota and Ono both had solo shows. Finally, Kubota, Ono and Shiomi all populated the ensemble of Shelter Plan by Hi Red Center, themselves frequent visitors to Naiqua.

All this led to Kubota’s December 1963 solo show, 1st Love, 2nd Love… at Naiqua. Filling the space with mountains of crumpled paper—“love letters”—then covering that in white cloth—“a beehive”—she staged a Happening and the documentation was sent to George Maciunas, the Fluxus founder in New York, per Ono’s recommendation.

With males atop the societal ladder and traditional female artists second, the avant garde, feminine Kubota, saddened by a lack of attention to her work, didn’t stand a chance. When travel restrictions relaxed in 1964, Kosugi agreed to join Kubota for a July 4 Manhattan relocation to honor Maciunas’ invitation, then reneged. Instead, Kubota and Shiomi went, welcomed to America by the quirky Lithuanian who housed them at Fluxus Headquarters. The two Japanese women joined a third, Takako Saito, who started assisting six months earlier, doing Fluxus mailings and pasting labels on curious art “products.” With Ay-O and Paik living closeby, the shopping and preparing of food for communal dinner events fell to Shiomi and Kubota who wanted authority to counter their odd host’s miserly, unhealthy meal plans.

Still, Kubota adored the unique Flux-leader and created two additions to his Fluxus mail order line: Fluxus Napkins, 1965, with magazine cut-outs of a woman’s mouth, and Fluxus Pills (Medicine), 1966, a clear plastic box of empty gelatin capsules, echoing Maciunas’ poor health. In 1965, Kubota edited Hi Red Center’s Bundle of Events, a Fluxus publication.

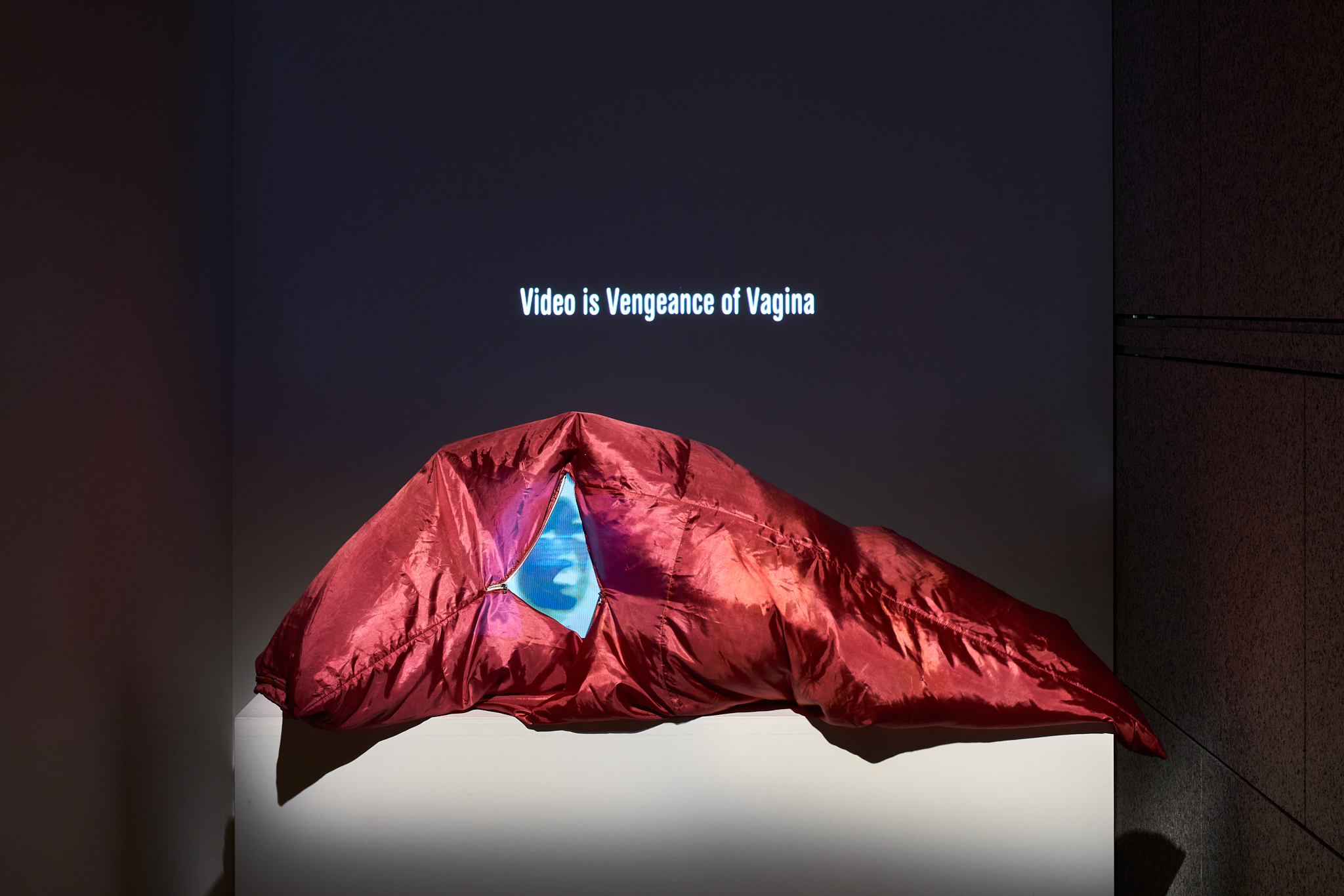

The ambiguity and complexity of The Vagina Painting strengthen her own position as an artist

But notoriety arrived on July 4, 1965 with Kubota’s Vagina Painting, performed at the Perpetual Fluxus Festival at the New Cinematheque, normally a movie venue, run by Maciunas collaborator Jonas Mekas. Despite stage fright, before a group of only ten or so Fluxus artists, Kubota, with a brush attached to her underpants, squatted and painted blood red abstract forms on paper spread across the floor. Reminiscent of menstrual blood, geisha references and Asian calligraphy, some saw it as a critique of macho action paintings by Jackson Pollock or Yves Klein’s use of females as painting tools in his 1960 Anthropometrics. Others were reminded of Zen for Head, a straight black line performed by Paik’s hair dipped in sumi ink mixed with tomato juice at an early Fluxus event in Wiesbaden, Germany in ’62.

Kubota’s stunning one-time-only event lives on in photographs taken by Maciunas, freeze-frames of iconic pre-Feminist art. Kubota revealed in a 2009 interview, “I was not so interested in performance. I did that piece because I was begged to do it… begged by Maciunas and Nam June.” In fact, it is unknown who conceived the piece. She continued, “It was an action painting. I participated [in the festival] because they asked me to.”

For some, this ambiguity and complexity enhances, not detracts from, Kubota’s powerful position. “Male or female, art is art,” she told the Brooklyn Rail. “People can put me in the Feminist category all they want, but I didn’t think I can make any real contribution other than my work as an artist.” Vagina Painting marked a turning point. She never performed body art again.

From 1967–69, she was married to the experimental composer David Behrman. In 1970, she moved to Los Angeles, following Paik, and in 1977, they married. But Kubota met Behrman in 1965 and the following year, participated in Sonic Arts Union performances with him, the late Alvin Lucier, and others. In 1967, Kubota and Behrman wed and toured Europe with the other performers and spouses including Mary Lucier, with occasional vocal contributions.

Kubota also performed as a Vietnamese woman in Carolee Schneemann’s 1967 multimedia work, Snows, expressing sorrow and anger about the War. Kubota’s six-page review for the Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo about a 1969 New York exhibition TV as a Creative Medium spread video art information internationally.

Then, the following year, Kubota’s first experiment came in video: a self-portrait: rough, colorized and tight with synthesizer enhancements by Paik and new collaborator Shuya Abe, a Japanese engineer. All three taught classes at the new famed L.A. art college CalArts.

In 1972, these experiences inspired Kubota to form a feminist video art collective, White Black Red & Yellow, a reference to the American flag and skin color, joined by Mary Lucier with Celia Sandoval, and Charlotte Warren. The group held two “multimedia concerts” at the Kitchen in Manhattan. Kubota next helped coordinate the first annual Women’s Video Festivals there in 1972-73.

Maciunas recommended Kubota to fellow Lithuanian filmmaker and the Anthology Film Archives founder, Mekas. If her 1972 work Broken Diary: Europe on 1/2 Inch a Day was not influenced by him, his groundbreaking autobiographical style found a kindred spirit. She documented her travels to European cities, Duchamp’s grave, visits with Josef Beuys and other performers. Kubota continued the diaries the rest of her life and left many in raw or partially-edited states.

In 1974, Kubota began a job as Video Curator at the Archives upon its reopening at 80 Wooster Street. Earlier that year, Kubota and Paik bought a coop through Maciunas at 110 Mercer Street.

When Sony’s Portapak, the first portable video camera, appeared in 1965, Paik acquired one immediately. Kubota followed five years later. after making suggestions to Paik about what eventually became her “video sculptures,” thinking he should implement them. “He didn’t listen to me, so I decided to do it myself,” she said. In 1983, Kubota, formally trained in sculpture in Japan, also said “I am a sculptor, I want to make video, but I also wanted to make objects.”

Maciunas and Mekas were mentors to Kubota, Paik, a life partner, but her father figure was Marcel Duchamp. Kubota met Duchamp by chance on a flight to Buffalo, NY in 1968, during a snowstorm. It was the opening night of Merce Cunningham’s Walkaround Time and she happened to have a Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo featuring Duchamp, which she told him about, and together they improvised reaching Buffalo in the storm.

When Cage, Marcel and Teeny Duchamp performed Reunion at its premiere in Toronto on March 5th, 1968, Kubota shot photographs. Duchamp beat Cage in 30 minutes. Then Cage and Teeny played, with Marcel observing until 1 am with the crowd down to 10 people. A few days later, Teeny won the game.

That was Duchamp’s last public appearance. He died later that year of heart failure at 81. His passing propelled Kubota’s series “Duchampiana” from 1972 to 1991 with each work subtitled. She began with Marcel Duchamp’s Grave, a plywood construction with 12 monitors, a floor mirror and shots of her at the Duchamp family plot in Rouen, France with her 1970 book of stills of the Cage-Duchamp chess match. The piece showed at The Kitchen in 1975.

Next, Video Chess, 1975, Duchamp and Cage playing chess while Kubota plays chess with a naked Paik. Nude Descending a Staircase, 1976, was monitors embedded in each of the four steps in a plywood staircase made by Kubota’s favorite carpenter-artist, Al Robbins, showing Super 8 film clips of a nude. Door, 1976-1977, was Duchamp and Old Faithful images. Bicycle Wheel, 1983, and Bicycle Wheel One, Two and Three, all 1990, feature bicycle wheels with small, five-inch color monitors attached to the spokes and motorized to spin. But unlike Paik’s carefully composed tripod studio shots, Kubota, dragging her heavy Sony Portapack to videotape Duchamp’s grave, wobbled from exhaustion, emitting emotion, creating a style: extremely personal, with grief elements that reach back to her Buddhist acceptance.

With the video sculptures and the story of her early years, Kubota will forever paint and tell tales in her own unique language

Barbara London, MoMA video curator, impressed by what she saw in the Nude Descending video, acquired it for the museum’s collection, their first video installation. “Nam June was stunned, “ Kubota later said, “It was I who had earned cash money.”

That wasn’t the beginning of Kubota’s and Paik’s separate but equal video friendship, but it was Shigeko’s groundbreaking push into the realm of Video Sculpture: portable cameras, magnetic tape, heavy decks and monitors collide with plywood, sheet metal, Mylar and mirrors, transforming time-based vibrations into solid monoliths to ponder and meditate on. Shigeko exploded the formal purity of the patriarchal Minimalist aesthetic prevalent then, infusing it with Fluxus-Intermedia anti-art, in service of her personal narratives. Her videos My Father, and later Korean Grave convey this solemn, mournful feeling.

And though they didn’t collaborate, per se, several Kubota works refer to Paik: Trip to Korea, 1984, Pissing Boy, 1993, Sexual Healing, 1998, April is the Cruelest Month, 1999, Winter in Miami, 2005-06 and a eulogy/homage to her husband in 2007’s installation, Nam June Paik I and II.

Kubota’s work peaked with nature pieces during the ‘80s, ’90s, and beyond, utilizing her own visual alphabet—rivers and mountains, waterfalls, rocks, and blossoms—intersecting with everyday life to unfold slow geological rhythms whose forms suggest Japanese spiritual traditions in works like her Bird and Tree series, Three Mountains, Riverrun, Niagara Falls and, for instance, Rock Video, where a five-inch monitor embedded in a boulder is surrounded by mirror shards.

From the mid 1960s, Shigeko Kubota was New York-based, always with strong Japanese ties. In addition to her Fluxus work, she singularly infused video into the sculptural realm, poetically uniting the personal and the technological, maintaining her strong female identity while cultivating relationships with superstars like Paik, Maciunas and Duchamp.

I have not mentioned her many exhibitions, collaborations and travels, a whole other series of Duchamp-related work or some of the red tape and side projects she guided as the “Vice-Chairman of Fluxus.”

But in 2014, Kubota said, “I realized writing is something that I can do with the camera.” She has also likened video technology to a “new paintbrush.” With the video sculptures and the story of her early years, Shigeko Kubota will forever paint and tell tales in her own unique language.

■Viva Video! The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota

Exhibition period: Until 23rd Feb. 2022

Venue: Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Art Tokyo Exhibition Gallery 3F

Address: Miyoshi, Kotoku, Tokyo, 4-1-1

Opening hours: 10 am to 6 pm (Tickets available until 30 minutes before closing)

Closed: Mondays (except 10 Jan., 21 Feb. 2022), 28 Dec. 2021, 1 Jan., 11 Jan. 2022

Admission fee: Adults 1400 yen, University & College Students, Over 65 1000 yen, High School & Junior High School Students 600 yen, Elementary School Students & Younger Free

*Ticket includes admission to the MOT Collection exhibition.

*Children younger than elementary school age need to be accompanied by a guardian.

*Persons with a Physical Disability Certificate, Intellectual Disability Certificate, Intellectual Disability Welfare Certificate, or Atomic Bomb Survivor Welfare Certificate as well as up to two attendants are admitted free of charge.

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)