Chief editor of FRUiTS Shoichi Aoki has been a witness of the streets of Tokyo since the 90s. We spoke to him about the changes in street style from the mid-90s to 2010s to now. In the first part, he mainly covered the years between 1997—when he founded FRUiTS—to 1999. Here, Aoki talks about his impressions from the 2000s to now.

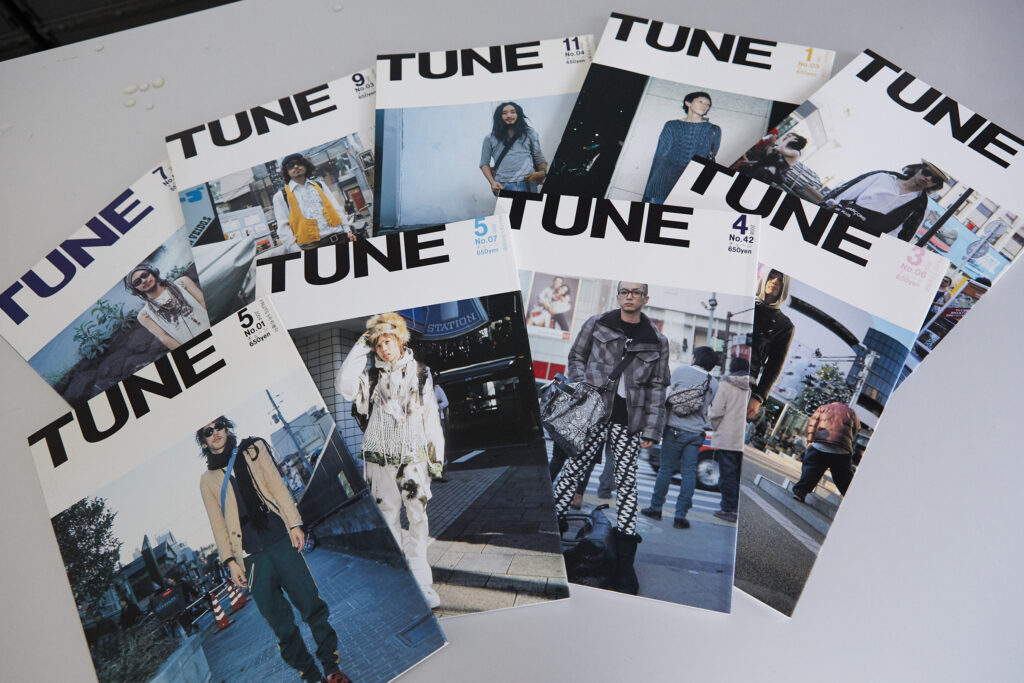

—(Continued from part one) Once the Urahara hype took over in the mid-90s, you began shooting mostly women for FRUiTS. You then published TUNE in 2004.

Shoichi Aoki (Aoki): Around 2003, a decade-ish after what we now call Urahara sprouted, a new style for men emerged. In my impression, the boutique CANNABIS was the thing that set it off. The staff there wore strange outfits. I still vividly remember their fashion show on the street in front of the store. I liked the fashion they showcased. It was kind of random. I don’t know how people would perceive it today, though. The style of the audience was interesting too.

The kids who had the Urahara mindset thought the clothes were uncool and weird. Even most of my staff were like, “I’m not sure about this.” Back then, Rei Shito was one of my staff, and she was close with the staff at CANNABIS, so she backed them up. I thought they were interesting too, so I asked my staff—who had taken photos of girls for FRUiTS—to take pictures of boys who had a CANNABIS-like style. That became TUNE.

It’s still a mystery how they had polished outfits right from the start. It’s not easy to give off that vibe, but they had a level of perfection that made it seem like they’d been dressing that way for years. A few years until that point, only Urahara fashion existed for boys.

—It seems like women didn’t buy into the Urahara wave at first.

Aoki: They didn’t for about three years. The difference between the direction of men’s and women’s styles was big. I feel like it was hard for pairs to be born. When the magazine mini came out in 2000, the girls started dressing in an Urahara way, and their hang-out spot changed from Harajuku to Daikanyama. I didn’t understand the style, so I asked other staff to shoot for FRUiTS.

—What were you interested in then?

Aoki: I wasn’t interested in anything (laughs). I was in a slump.

—How long did that last?

Aoki: For about five years. Even after my staff began shooting for FRUiTS, we were pretty well as a platform. Looking back, the most stylish people in Harajuku moved towards Daikanyama-esque fashion, so the quality of the styling was high and polished. Imported products became the main thing, and stores like grapevine by k3 and other stores by stylists came out. Fashion in London was being refined then, so maybe that was an influence, too. That was probably around the time I shot Lotta Volkova on the streets of London for STREET.

—If what you’re describing was a period of transition, I feel like we’re in another one right now, where people are trying to break through the refined nature of fashion.

Aoki: Right. That’s why I’m excited about what’s to come, and I want to do something too. Some people are still diehard fashion lovers, but the business isn’t full of life, and teenagers no longer know what to wear. The vibe right now is similar to when the DC craze ended. It all depends on the situation after the pandemic.

A new shift in fashion during the late 2000s

—Let’s go back in time a bit. Once we entered the 2000s, fashion became refined and relaxed. What happened after that?

Aoki: When everybody was waiting for Harajuku fashion to return, the boutique, Faline, opened in 2004. Maybe the store staff’s loud style and color usage were the catalysts for change. Until then, Nakao-chan was the only person who didn’t stop wearing loud outfits in Harajuku. It’s possible for just one person or store to change the direction of Harajuku fashion. Around 2010, Kyary Pamyu Pamyu came onto the scene. And Harajuku fashion came back very slowly.

—I clearly remember when Kyary Pamyu Pamyu first came out. A lot of people I knew were like, “I don’t get it!”

Aoki: Kids that thought Daikanyama fashion was boring started wearing incohesive outfits. I feel like young people also wanted to revive Harajuku fashion. Ayumi Seto first appeared in FRUiTS around then, and we put her on the cover right away. She still had this innocent look, and the clothing items she wore all had different vibes. At first glance, it seemed like it was a mistake. But then I thought she was doing it on purpose, as a reconstruction of that refined Daikanyama fashion. This might be my individual interpretation, but the role of FRUiTS was to highlight people like her who [wore clothes] their own way. Looking at Seto’s career since then, I believe that was the real her. I’m not sure what she thinks, but she did a great job.

However, Harajuku fashion didn’t explode [in popularity] after that. The era of fast fashion arrived.

—Right.

Aoki: While receiving the impact of fast fashion, store staff became icons in Harajuku fashion. Because of the influence of the Daikanyama-esque era, people had this odd habit of polishing their style. The level of the iconic store staff’s style was so high that kids who wanted to get into fashion felt like they didn’t stand a chance. I mean, it was inevitable.

—The styling skills of the mainstays improved, and younger people couldn’t keep up.

Aoki: The bar was set too high for newcomers.

—I see (laughs). I thought fashion was made of the repetition of mainstream movements and movements that reacted against it. But it seems like it’s layered on top of one another like a mille-feuille. It’s impossible to talk about fashion by cutting each piece apart.

Aoki: People say that history repeats itself, but the history of Japanese fashion isn’t that long, so it’s still in the first cycle.

Geniuses that change the zeitgeist

—I see that you’re the type of person who wants to observe different fashion styles, even if you don’t like them. That’s very journalistic.

Aoki: The range of styles I like is wide. At times, I don’t distinguish them by categories. Looking back at the staff I worked with, the scope of fashion they could grasp was narrow.

I like [it when people] coordinate an outfit, so I like all types of looks aside from the ones comprised of only one brand. I’m okay with people wearing Martin Margiela from head to toe. There’s a reason behind that, though. In that sense, I didn’t really like gothic Lolita outfits. It seems like people associate FRUiTS with that because recently, people have been reaching out to me about gothic Lolita photos. In actuality, I only featured a few gothic Lolita photos in the magazine at the beginning. It was an intriguing phenomenon. I should say this just in case; gothic Lolita and Lolita aren’t the same.

—I assume cosplay-ish styles aren’t your preference because they’re separate from fashion.

Aoki: Cosplay isn’t fashion; it’s cosplay. It’s separate from everyday life. But some people bring that to Harajuku. Because it’s a city where different styles are allowed, it accepts that. I avoid shooting that because it’s different from shooting street style. If you look at one photo from the peak of Decora style, you’ll see that it was so loud and didn’t look that different from cosplay. But there’s a backstory to how those people got to that point. For them, it was street style.

—So, you’re still okay with people wearing Off-White from head to toe (laughs)? I apologize for being so persistent.

Aoki: Well, it’s not cosplay (laughs). Not many people in Japan have the attitude and financial means to wear Off-White from head to toe. I don’t think Virgil (Abloh) himself expected people to wear Off-White all over. Street style, according to him, is about having fun with coordinating outfits. The brand’s role is to [provide] staple products for that. In my view, Chinese people who wear Off-White from head to toe look nice, in terms of both attitude and financial means. It’s much better than office workers who wore Armani all over during the economic bubble era in Japan.

Also, we shouldn’t forget that Garçons and Martin Margiela were criticized in a similar way by fashion insiders, especially the media and fashion critics, at the beginning of their careers.

—It’s not rare for people in fashion to have a negative view of monogram culture, as well as Vetements selling a shirt at an outrageous price.

Aoki: Really? They were witty enough to steal a DHL shirt design and sell it for 100,000 yen. It was like they were raising a question. In the context of contemporary art, they created simulationism. Perhaps it was the antithesis to the price collapse brought on by fast fashion. And the audience answered their question. If you don’t like something, all you got to do is not purchase it. This applies to Virgil too, but they’re geniuses, so I don’t think people should interpret their work carelessly. They’ll regret it later (laughs). Not unlike baseball players who criticized Ohtani for being a two-way player.

You can’t do anything about monogram culture. Those people have that desire. As someone who experienced wearing Lacoste’s crocodile-embroidered clothes, I’m not in a position to say anything. I’m sure I’m not making sense right now (laughs). It’s appealing. It’s a big challenge for designers to deal with this matter. Perhaps the DHL shirt embodied that.

—I didn’t know brands and their audience have a complicit relationship.

Aoki: When Vetements first showed their collection in Paris, they had a loyal following from the start. By their next season, many people wore their clothes. As an audience, the reaction was like, “Finally!” At the same time, (John) Galliano had been appointed as the creative director of Martin Margiela and presented a collection as Maison Margiela. It was drastically different from the brand until that point, so many fans were against it. After Martin quit and before Galliano was appointed, Demna (Gvasalia) was the designer of [womenswear], and he started a new brand. He inherited the oversized silhouettes of Margiela, which in my interpretation, is the narrative that made people support the brand.

—When FRUiTS ceased publication in 2017, you said the reason behind that was because “stylish people no longer hung out in Harajuku.” I got the impression that Japanese fashion itself was dying from your statement. Do you have a feeling that it’ll revive?

Aoki: I’m sure everyone’s forgotten this by now. Back then, fashion was in a bad place because of fast fashion. Many people asked me in interviews if fashion was ending. I thought it was going to be over. But I had faith in the styling skills of Harajuku girls, so I thought it would work out. We’re at the crossroads of whether or not fashion will die again due to covid. I still believe in the styling skills and desire of Harajuku girls, though.

Just so there are no misunderstandings: UNIQLO isn’t part of my definition of fast fashion. That’s a separate entity.

—Do you think that time’s coming soon?

Aoki: It’s in the air. I think people are frustrated, fashion-wise, because of covid. One or several game-changing geniuses have historically changed fashion drastically. The DC craze was [defeated by] Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, and Urahara was [started by] Hiroshi Fujiwara and others. Demna and Virgil might’ve been the ones who [helped us] escape two or three fast fashion companies. I guess I’m waiting for the genius of Harajuku to arrive.

—What’s next in store for you?

Aoki: The role of FRUiTS is to stay up-to-date with small movements that no one notices, so I’m doing fieldwork in Harajuku every day. Even though the publication of FRUiTS ended, I still sometimes take pictures of girls I like with my smartphone. I want to give it some form and bring FRUiTS back.

Shoichi Aoki

Photographer and chief editor. CEO of Lens Co., Ltd. Born in 1955 in Tokyo. After having a career in programming, Shoichi Aoki published STREET in 1985. He published FRUiTS, a collection of authentic portraits of the streets of Harajuku, in 1997 and attracted a global audience. After that, he put out the men’s version of FRUiTS called TUNE and .RUBY.

Twitter:@FruitsMag

Instagram:@fruitsmag

Instagram:@fruits_magazine_archives

Instagram:@streetmag

Photography Kazuo Yoshida