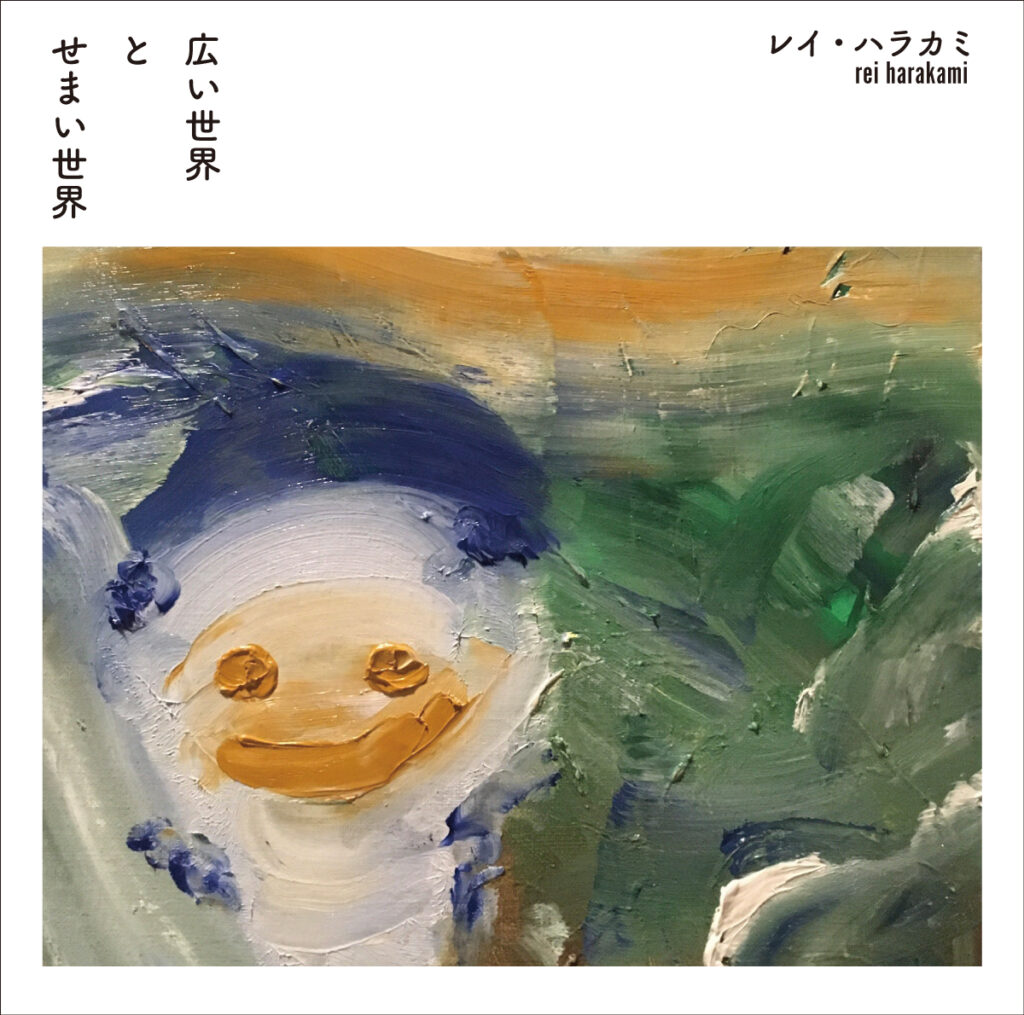

In 2011, one-of-a-kind musician Rei Harakami departed from this world. But to this day, many still listen to the music he made during his lifetime. In December of last year, his legendary cassette tapes, Hiroi Sekai (1991) and Semai Sekai rei harakami selected works 1991~1993 (1993), were remastered and reintroduced to the world as Hiroi Sekai to Semai Sekai.

In honor of this release, we’re releasing a short series of three articles that reexamines Harakami’s career path from the beginning. In our first article, we interview filmmaker Yasuto Yura, one of Rei Harakami’s university peers who would later become one of his long-standing friends. How did Rei Harakami feel about making music at the beginning of his career? And how did Rei Harakami go from filmmaker to musician? Yura, who lives in Kyoto, spoke to us over Zoom.

* For this interview, I referred to the June 2021 issue of Eureka, “Special Feature: Rei Harakami” (Seidosha).

Rei Harakami had a preference for analog—then he encountered the computer.

――You first met Harakami when you were studying film at the Kyoto College of Art. What was your first impression of him?

Yasuto Yura: Harakami and I first met when we were helping an older student out with their film. Harakami was a second-year student at the time. I was making sound effects, and I think he was helping as a regular staff member. My impression of him was that he was a really cheeky guy. He spoke what was on his mind, so he was quick to express any complaints. But it wasn’t like he just didn’t want to work. He just wasn’t afraid to speak up when something was wrong, or the work could be made more efficient. I think that never changed, even in his later years. But back then, he was about 20 years old, so I thought he was cheeky. (laughs)

――Did you have any idea that you’d become such good friends when you first met?

Yura: No, not at all. (laughs) There were times when we both went out drinking with a group or were at the same wrap party. But before I knew it, he started showing up at my room unexpectedly or waiting outside my apartment for me to come home from my part-time job. (laughs)

――After that, you became such good friends that you’d go out drinking together three times a week. What led to you two finally hitting it off?

Yura: At the time, he and I were the only students who designed our own sound for our films, at least to my knowledge. I used a computer, and he made more analog music using cassettes. Harakami said that he didn’t like computers. If anything, he was more into improvisation, so he wasn’t really interested in playing and performing using a computer, which is more fixed. He used to barge into my room with a bottle of sake all the time, and when he saw my Roland MC-500 sequencer and other gear I was using at the time, he asked half-jokingly, “What do you do with this?” So I showed him how to use it. He started fooling around on it, making random stuff. He was completely absorbed in it for a while and asked me, “What do you do when this happens?” Looking back on it now, I feel like even back then, what he was doing was rather complicated. But after working for a while, he’d be like, “I got it!” And after that, we’d get wasted. (laughs) I wasn’t necessarily the reason he got into it, but I think maybe he was able to experience something he hated and feel an affinity for it. Or he realized that it was interesting depending on how you used it. I think this was after Hiroi Sekai came out, so maybe that was around when we started talking more.

――I see. So it all started with the computer.

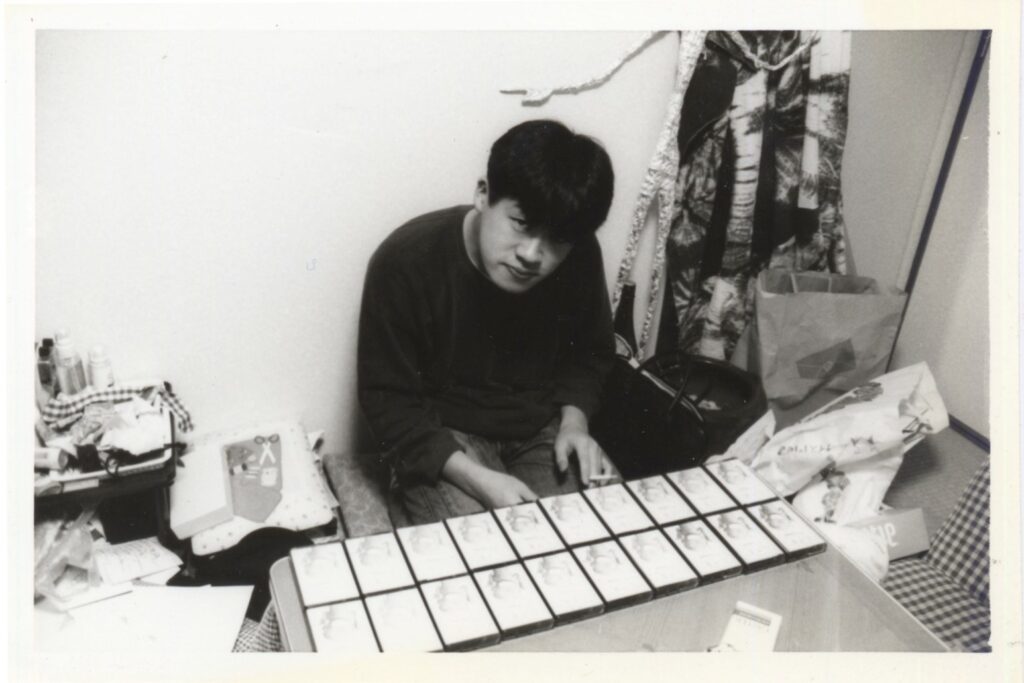

Yura: Back then, his year was having a film exhibition, and he was selling Hiroi Sekai tapes there. I stopped by that exhibition, and I remember he asked me to buy his tape, so I did. Recently, I visited that same gallery where the exhibition was held because I had some errands there. We started talking about Harakami, and the gallery owner also had the tape. (laughs) I don’t think there are many of those tapes out there. He probably only made about 20 of them. He worked really hard to make them, dubbing everything manually.

He also did illustrations, so he used to make flyers for exhibitions and such using the convenience store copy machines, which were finally able to make color prints. But he didn’t use it in the traditional way. Instead, he’d use the copy machine as an effect. He’d go through the trouble of making the illustration small and enlarging it on the copy machine to make the quality rough on purpose. He seemed to like things like that: figuring out how to use existing technology to alter something. He did that with sound and film too.

――What kind of films was Harakami making at the time?

Yura: In the early days, he mainly made animations. The song “Isudetabi,” which was on the same label as the latest release, originally came from a film of his friend moving around while sitting on a chair. He used the song for that film. Later, he made experimental works that reimagined the structure of stories and films.

――In terms of filmmaking, Voyant, which Harakami made in 1995, was his last work before he became a musician. As his senior in the same industry, how did you feel about Harakami as a filmmaker?

Yura: I thought he was the most interesting, at least of the people I knew. I always kept him in mind, and he probably kept me in my mind, too. We never said it directly to one another, but I wanted to leave him speechless with my work, and he wanted to compete with me, too. So when my work was bad, he would make sure I knew. (laughs) I wouldn’t say we were doing it consciously, but once one of us finished a piece, we’d talk about it over some drinks. Looking back on my days as a student, having him there was very important.

An important document of how Rei Harakami went from filmmaker to musician

――At the end of last year, the remastered editions of Hiroi Sekai (1991) and Semai Sekai rei harakami selected works 1991~1993 (1993) were released. These tapes date back to before Harakami became known as a musician. What was Harakami’s attitude in regard to making music?

Yura: Back then, he was making music for people’s films. Most of the songs on Semai Sekai are from that—basically, it was music he had composed for people’s film soundtracks. He was skilled at making music, so classmates started asking him to make music for them. First, there was the image of the work, and then the film, and Harakami would figure out what kind of music to add to that. In a sense, it was the beginning of his client work.

――I see.

Yura: Back then, I worked as a tech staff member at the university. I was helping to select the gear and software that would be installed in the new video and audio production facility. So I introduced Mac, the sequencer software EZ Vision, and the Roland SC-55 sound module (Editor’s note: The SC-88 PRO, a later model of this equipment, would be one of Rei Harakami’s favorites into his final years of life). From there, Harakami learned how to use these in class. I think that’s when he started using the computer to create music. “Kujirayarou no Tema” from Semai Sekai makes great use of the SC-55.

――This work documents the process of how Harakami, a guitar and bass musician, set down the path of becoming an electronic artist. In a way, it was like the start of Rei Harakami as the world knows him.

Yura: That’s true. Semai Sekai might be the tape that started it all. Hiroi Sekai was his world before that, and his world after that was Semai Sekai.

――How did you feel about the process of Harakami changing?

Yura: Before making this cassette, Harakami hated computer and techno music. But he suddenly became absorbed in it, so I did think, “That’s different.” Since he could record the tape in one shot, he didn’t need to dub it as many times, so the sound quality became clearer, and the sound was much better. But Harakami didn’t like it to sound too high-quality, so he would sometimes try to “dirty” the sound quality on purpose.

――Why do you think Harakami became so absorbed in computer music?

Yura: For one thing, he probably realized that he could express all kinds of small nuances with the computer. Also, he got into polyrhythm around that time, so I feel like he must have realized that when he incorporated that into his own songs, the computer was more convenient than playing instruments.

――The songs in both albums leave an impression with their diverse sound: They feature a raw physicality, piano playing that sounds improvised, elements of blues-rock and folk, and a collage-like quality that aren’t present in Rei Harakami’s later works. How did you feel when you first heard these albums?

Yura: I thoughtit was unusual for him to make this kind of music. It doesn’t sound like music from a band or a computer, and it isn’t music that’s easy to understand. There’s a unique, floaty feel to it, which I thought was interesting when I listened to it. Although I didn’t think it would sell. (laughs) Regarding the diversity of the sound, I think Harakami mixed all kinds of music within himself, and that was his output. But Harakami would never say what music had influenced him. (laughs)

Rei Harakami’s world—his “sekai”— will never fade away

――Many listeners will listen to these two re-releases for the first time after listening to Rei Harakami’s other music. How do you feel when you revisit Rei Harakami’s earlier music from a modern perspective?

Yura: In many ways, I think that it was because of these works that the later Rei Harakami came to be. That kind of work doesn’t just come out of nowhere. There was a Harakami even before this tape, and everything is connected. After Semai Sekai came out, Harakami started receiving work requests from all kinds of people. From there, music started to become his job. But back then, he still felt strongly about wanting to be a filmmaker, so he was really torn. At one point, I’d said to him, “You get this many compliments and work requests from your music—why don’t you turn that into your main job?” About two weeks later, Harakami told me that he was going to debut through Sublime [Records]. I was happy for him. I think Harakami wanted closure with filmmaking, so he created Voyant (1995) to bring a conclusion to his filmmaking career.

――Harakami’s music transcends borders and time, and is still listened to today. Why do you think that is, and what do you think is the appeal of his music?

Yura: I think about that sometimes. I believe it’s because he made things that hadn’t ever existed in this world, and that’s been true since he was making films. I think he hated going along with the scene or being put in a category, so he used his own methods to make whatever he wanted. I mean, isn’t every Harakami song immediately recognizable as one of his? There won’t be any new songs, but he made music that was so original that you instantly know it’s Harakami when you listen to it. I don’t think that will ever fade away. I still listen to his music from time to time, and it never feels old. His music had its own unique universe. And I think that was born from Hiroi Sekai and Semai Sekai. Some people use various techniques to make songs that go with the current trends, but Harakami made music separate from that. That won’t change whether ten years pass or 100 years pass. They aren’t songs or sounds that feel like they belong to a specific era. They don’t get old, and even today, people can still listen to his music normally.

Yasuto Yura

Yasuto Yura began independently creating films in 1991. He’s shown his work in Japanese cities such as Kyoto and Tokyo, as well as Europe and other Asian countries. In addition to filmmaking, he also produces various other works, including installations, collaborations, books on computer technology/introductory design, and CGI animations. He currently teaches film production at Osaka Electro-Communication University and is a part-time lecturer at Ryukoku University. Other roles he holds include Organizer of VIDEO PARTY (a group that holds film screenings), Program Director of Lumen Gallery, and planning committee member of the Kyoto International Student Film & Video Festival.

www.yurayas.net

レイ・ハラカミ『広い世界 と せまい世界』(rings、2021/12/29)

https://www.ringstokyo.com/rei-harakami-hiroisekaisemaisekai

Construction Syunsuke Sasatani

Translation Aya Apton