Ichiko Aoba is a musician who’s been building her own fantastical, sonic world with her gentle yet rich voice and poetic classical guitar. She recently released her latest album, Windswept Adan, two years after her earlier one. After her lengthy stay in Okinawa last January, she came up with a fictional story, which she later conceptualized into “a soundtrack to a fictional film.” The album shows how Aoba broke new ground as an artist. For instance, aside from the guitar, Windswept Adan features a roster of lush instruments, such as the piano, strings, flute, and harp.

Two co-creators have contributed to Aoba’s expression of her newfound creativity; musician Taro Umebayashi, who co-composed and arranged all the songs off the album, and photographer Kodai Kobayashi, who worked on the art direction and photography. How was the album born? Writer Tomofumi Hashimoto, who was in Okinawa at the same time as Aoba, speaks to the three creators.

Translucent sea grapes, and how the word “adan” inspired a story

—Before we get into your new album, how did you, Ichiko-san, meet your two collaborators?

Ichiko Aoba (Aoba): Last year, I released a 12-inch EP called Karaki to Amaneki with beatmaker Sweet William. And Kodai-san shot the cover art and booklet. That was when I first met him. His photos were pretty, and the way he captured light resonated with me.

Kodai Kobayashi (Kobayashi): To a certain extent, most musicians have a particular way of getting shot, but Aoba-san didn’t have that. When I shot the cover for Karaki to Amaneki, Aoba-san drew circles on the ground. Think hopscotch. Then, all the kids at the park started following her. I remember how fun it was to shoot something unpredictable. You can call it a happy accident or that feeling you get when something is on the verge of happening.

Aoba: The first time I worked with you, Umebayashi-san, was when we made a song for a commercial, right?

Taro Umebayashi (Umebayashi): The first time we met was to make a song for a commercial, but the first song we created together outside of that was the single “amuletum,” released in January 2020. This song is on the album, amuletum bouquet. Ichiko-chan and I belong to the same agency, and I always marveled at how she creates experiences akin to reading a novel, with only her guitar and voice.

Aoba: Behind my classical guitar and voice were sounds only I could hear in my head. I had a specific image of the sounds. Like, “This is where the oboe melody goes, the clarinet trio goes here, and the harp goes there.” I spoke about this to Umebayashi-san, and when we recorded “amuletum,” most of the sounds I had imagined came to life. The process was smooth because he knew what melodies I wanted and hoped for, even without explaining them with words.

—I heard you didn’t make Windswept Adan alone, as it’s the manifestation of everyone using their imagination together. How did you take the first step to create this album?

Aoba: When I was in Okinawa in January 2020, Kodai-san came to the island after I parted ways with you, Hashimoto-san. Kodai-san drove me around Zamami island, and he said, “Those are adan trees.” That was the first time I learned about it. We spoke about it, with me being like, “Hm. So, is adan edible?” and him being like, “Yeah, but I heard it’s not that good.” While we were going back and forth, the phrase windswept adan had already popped up in my mind. I remember telling him, “If I were to make another album, I think I’m going to call it ‘Windswept Adan.’” After the drive, we went back to the main island to go to this izakaya called Urizun. An epiphany struck me when I picked up a piece of sea grape and saw how translucent it was. I put the dishes to the side, put down my notebook, and wrote, “There were no words on the island.” The plot unfolded from there.

—It’s common to hear writers prepare the plot before writing a story, but why did you decide to do that with an album?

Aoba: Umebayashi-san told me, “I want you to write the plot because that would be the map for songwriting.”

Umebayashi: What Ichiko-chan said about placing the oboe or the harp in certain parts is similar to the idea of opera. Because opera is a comprehensive art form, when everyone shares something, the worldbuilding becomes stronger. I asked her to write the plot down just before she went to Okinawa because I thought it would be something that could be shared evenly with not just Kobayashi-kun and Toshihiko Kasai-kun, the mastering and mixing engineer, but everyone involved in the album.

Aoba: That’s why I stayed in Okinawa, knowing I might create something. Just when I felt like I didn’t have any inspiration to work off of, Kodai-san told me about the adan tree. That and the translucence of sea grapes triggered the inception of a story. I finished writing it around October; I wrote and rewrote it right until the album was in its mastering stage. As the songs gained more meat to them, Umebayashi-san would make demos. And that gave me the strength to polish my writing, which led to me rewriting some parts. Kasai-san would read that and be like, “Let’s change how it’s mixed then.” Umebayashi: A lot was born from our interactions with one another.

Connected by inspiration, everyone put out the same amount of energy

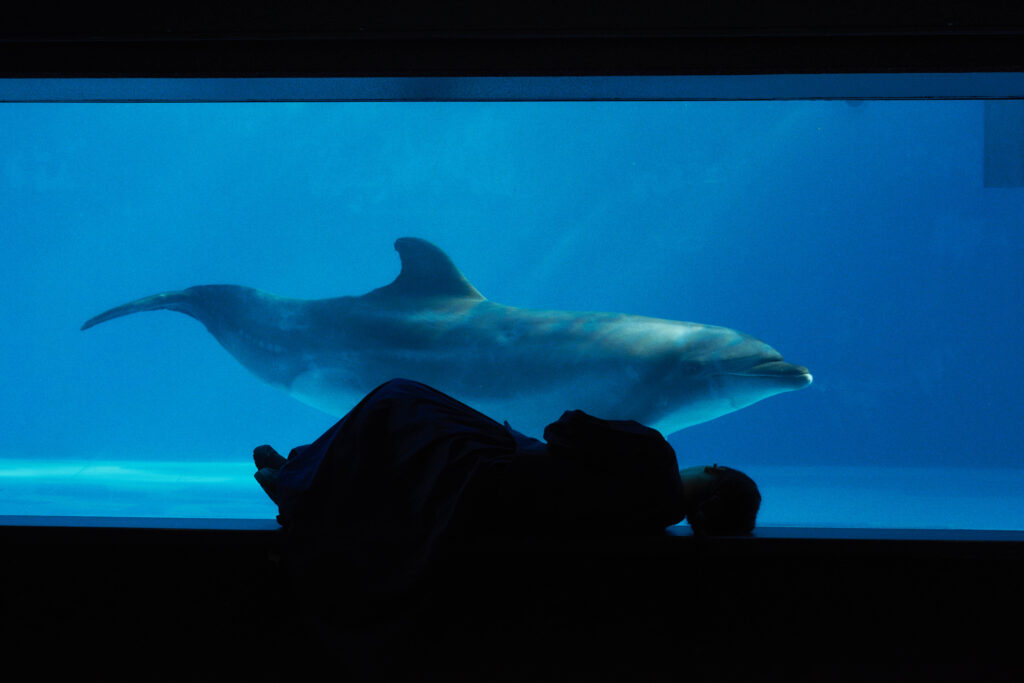

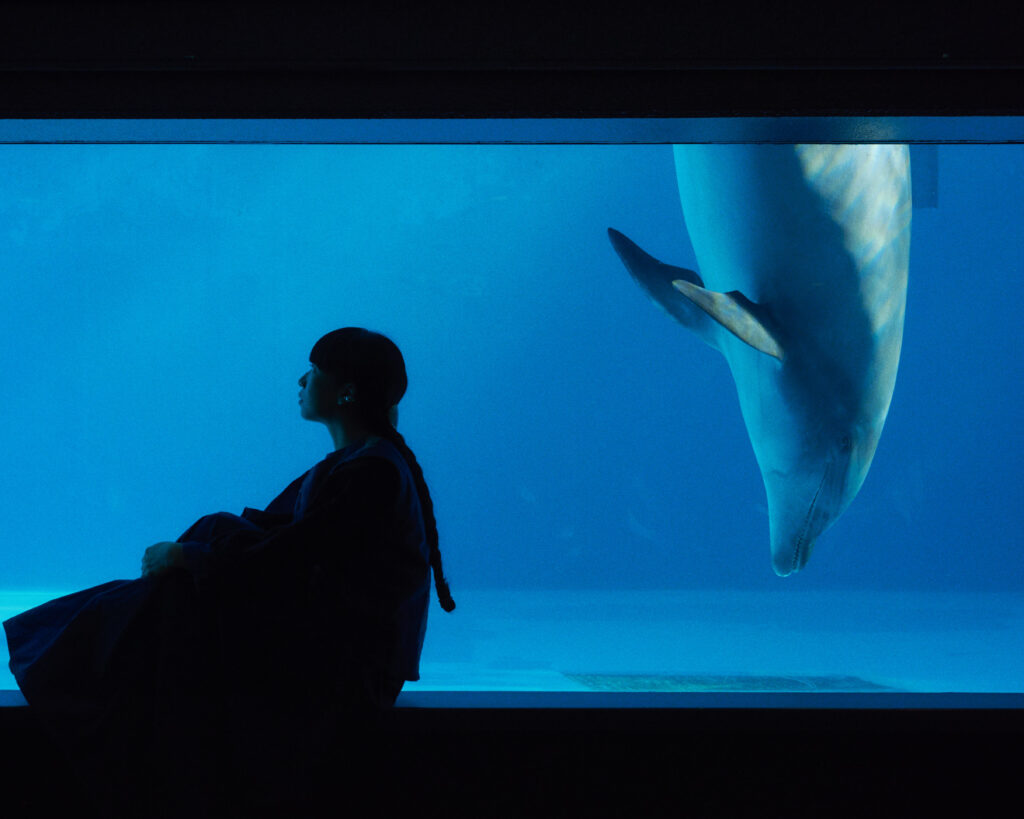

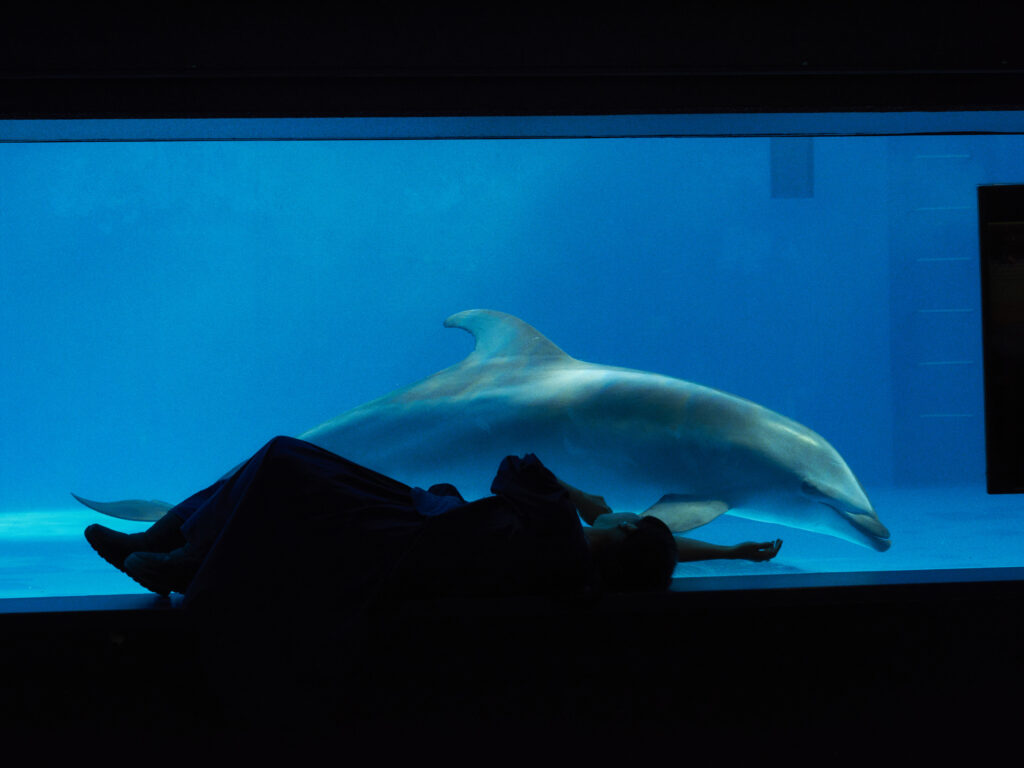

Aoba: We worked in a broad, loose way from start to finish. Sometimes once Kodai-san’s photos were almost complete, Umebayashi-san would look at them and compose a song. Usually, designers and photographers get involved in the visual part of the process, but it was a refreshing balance because Kodai-san was there from the beginning.

Kobayashi: It doesn’t happen often. It’s common practice to receive the completed songs and then think about ways to build the visuals from there. I’ve never really experienced making something like this with other people, so it was interesting. It was exciting to think my point of view might affect the music. The plot itself was still unfinished, so it was like running into unknown territory. There was no right or wrong with the photos; I was free to take whatever I wanted. We judged the images on whether the vibe was good, so the criteria were fuzzy. I’m unsure if “fuzzy” is the right word…

Aoba: When you look at things in a fuzzy way, you heavily lean on your intuition. If you could connect with your intuition rather than your thinking, then I think that means you’re in touch with something deep in your heart. Everyone was inspired equally, which is the step before being imaginative, and that’s why the foundation for Windswept Adan is so strong.

Kobayashi: Having a playful spirit played a massive part.

Umebayashi: I think everyone on the team shared that spirit. It wasn’t about being stuck in your role, like “I’m the composer,” “I’m the photographer,” or “I’m the lyricist.” Everyone put out the same amount of energy, and that’s what I’m proudest of.

Accepting the light, the return of conviction

—I don’t mean to force the connection, but because you made this album in 2020, I believe the things you felt during the year are reflected somewhere on the album. What did you feel over this past year?

Umebayashi: This situation allows us to be aware of the meaningful things in front of our eyes. What I want to express through music is that everyone can realize such things. It doesn’t take someone with exceptional talent. I wished to convey that the most with this album. Also, thanks to everyone working together, this album became something to be proud of.

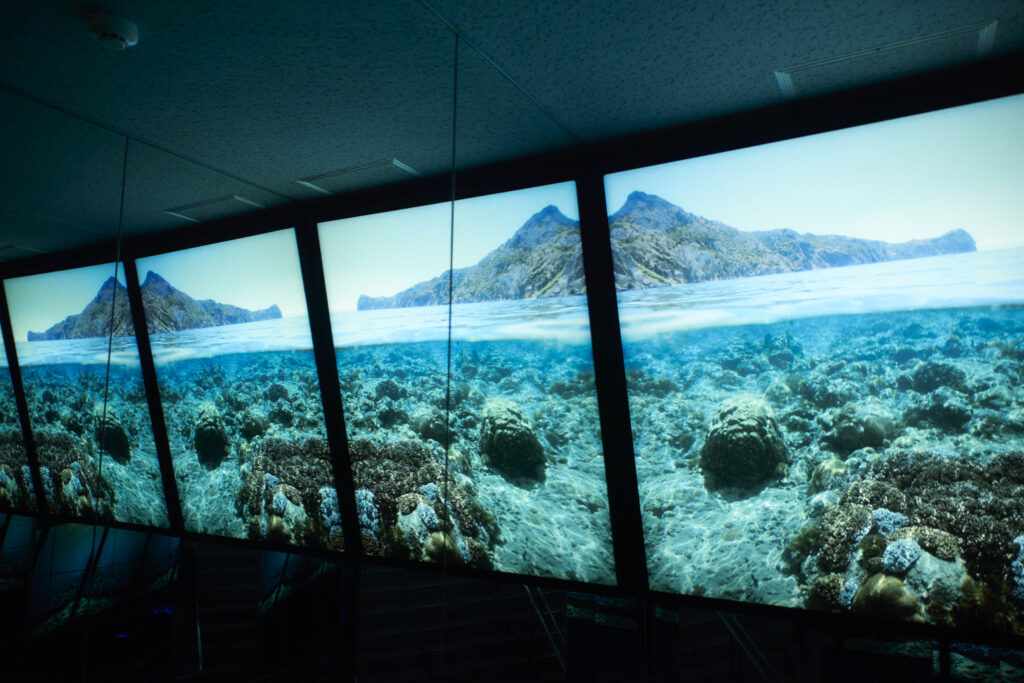

Kobayashi: I spoke about this with the production team thoroughly: our senses became sharper by the day because we stayed at home for a long time. Eating, touching, walking — all these senses. I decided to be conscious of the things that happened in front of my eyes. I welcomed the blowing of the wind and the blooming of flowers as a part of my body. That’s what I wanted to value, and I think that informed the photos I took for Windswept Adan.

Aoba: I can deeply relate to what Kodai-san said just now. Living in Tokyo, my ears pick up on many sounds, partially because music is my occupation. When the city became quiet, I realized I had unknowingly developed the ability to shut out the noise. My ears had hardened from the city noise, but they began to soften slowly. It was as if my hearing had reverted to when I was born. And what I started hearing was my inner, dormant voice; until that point, the outside noise drowned it out. It became easier to immerse in it because of how clear it sounded. I would ask myself questions and find out how I felt and thought. It’s not just my hearing, though. My sense of smell and sight also improved similarly.

In terms of life itself, I would wonder, “Why do planktons light up?” Many artists I know use the word “light” with care, and when I genuinely, wholeheartedly accepted that word, this feeling like conviction came back to me. It was a year where I felt like I could live on because of this conviction I gained. It’s like I got a lucky charm.

—Do you mean your understanding of “light” changed?

Aoba: This goes back to what Umebayashi-san said. Something important doesn’t necessarily equate to something bright. For instance, the feeling of “It’s not raining today. The sun is out” is a special feeling. This is because something you took for granted is, in fact, valuable. If a big earthquake hit us right now, we might die. If you got coronavirus tomorrow, you might die silently and alone in your home. These possibilities are everywhere, every day. Each and everything, from “I can’t see them from here, but a certain someone is living in a faraway place” to “A sea turtle is swimming in the ocean of Zamami,” felt illuminated with light. It was like being surprised by magic from moment to moment.

Imagining the first plankton emitting light, feeling surprised forever

—The listeners of Windswept Adan also lived through 2020. Was there anything you were particular about, such as what sort of demographic you wanted?

Aoba: Making sure the album could reach far into the future was a big theme. The lyrics and the music are quite personal, and I didn’t want to make the album only for those living in the present. Early on, I spoke about how I wanted to make something for creatures living 300 years later with the team. Also, I think Kasai-san had a strong desire to capture the atmosphere, not just the visible sounds. We used a mic that could record every single sound in the room and placed it at the best spot. That’s how we tried to record the album to reach those in the future. What about you, Kodai-san and Umebayashi-san?

Kobayashi: I still can’t explain what I shot. Kasai-san said, “I still don’t know what I made,” and I understand him in that regard.

Umebayashi: We all have our separate universes, and I think Windswept Adan is one stepping stone we have in common. Ichiko-chan and Kobayashi-kun will probably create more of these “points” down the line, and I think this means of expression fits the era we live in today. I’m not sure how humanity and the ecosystem will be like 300 years from now, but if we create works that uphold order, then I think that might speak to others in the future. I feel like we’re at a stage where we’re exploring undiscovered orders. Because Windswept Adan is another stepping stone, I think this will connect to the next piece of music. I hope I can work with this team again.

Aoba: Umebayashi-san and I spoke about this over the phone. Windswept Adan won’t end here, as it’s the first opening. It’s just the beginning.

—I’m intrigued by your idea of “300 years later.” The fact that this album might reach someone 300 years later, where the language and culture might look different, is the same as how we’re receiving signals and signs from those who lived 300 years before ourselves.

Aoba: The lyrics of “Dawn in the Adan” are precisely about that. We’re here talking to one another today thanks to those beyond Ohigan (a Japanese holiday when people visit the graves of their late family). Our grandmothers and their grandmothers and so forth — I’m so overwhelmed by that. And I’ll forever be. I’m also amazed by how we’re still alive, even though we started conversing a while ago. When I say “300 years later,” I’m talking about the far, far past. I’m tracing back to when the first plankton was born.

This is a personal memory but, when I played the role of Eh-chan in the theater piece cocoon in 2015, I felt like I was going to die with each succession of the sound of a gun. I can’t say if I was really on a sandy beach, but I can say what I had experienced was real to me. I went through that and live through music today, so I can’t help but feel overwhelmed by everything.

The first plankton to be born must’ve felt startled but happy. After learning of its loneliness, it must’ve lit itself up to find a mate. I want to carry that plankton’s force with me and live my life. I hope to remain that way, even after my physical body dies.

Kobayashi: I feel like we’re expressing the distance of 300 years by trying to transmit that light in its purest form. If you can express your amazement or emit a light that says, “I’m here,” it will reach someone, even if the amount of light is small. It could be slow or light speed.

Aoba: I mean, the stars we see are from long, long ago. Kobayashi: “How can we transmit that light without damaging it?” I think we all thought about that and had fun making the album.

Ichiko Aoba is a musician born on January 28th, 1990. She released her first album, Razor Girl, in 2010 and has released six albums since then. With her voice and classical guitar in hand, she plays her music across Japan and the world. Aside from singing, she works in many fields. Ichiko Aoba also works as a narrator and creates music for commercials, theater, and art festivals. She founded her label, hermine in 2020, the tenth anniversary of her debut. She continues creating warm, fantastical worlds.

http://www.ichikoaoba.com

Twitter:@ichikoaoba

Taro Umebayashi is a composer and arranger. He graduated from the Department of Composition at the Tokyo University of the Arts. As [milk], he released his first album, greeting for the sleeping seeds, in 2012 via Rallye Label. He works across diverse fields like music production, composition for other artists, soundtracks, anime music, and music for commercials. He is assiduously working on his second album.

http://piano.tt/umebayashi

Kodai Kobayashi is a photographer born in Niigata prefecture. Aside from working on the art direction of Windswept Adan, he has also directed the music video for Porcelain, which is available to watch now.

Photography Kodai Kobayashi

Translation Lena Grace Suda