In honor of the late Rei Harakami’s rare cassette tape re-release Hiroi Sekai To Semai Sekai, we’re kicking off a short series of three articles. In this second installment, we present an e-mail interview with Mark “Frosty” McNeill, founder of the L.A. Internet radio station “dublab,” who discovered Rei Harakami’s music in real time. The questions were posed by Masaaki Hara, a music journalist and label producer who was a close friend of Rei Harakami before his death and has also known Mark for many years (Hara Masaaki is also the director of “dublab.jp”, the Japanese branch of “dublab”).

My first memory of listening to Ray Harakami’s music. What I felt when I saw his performance.

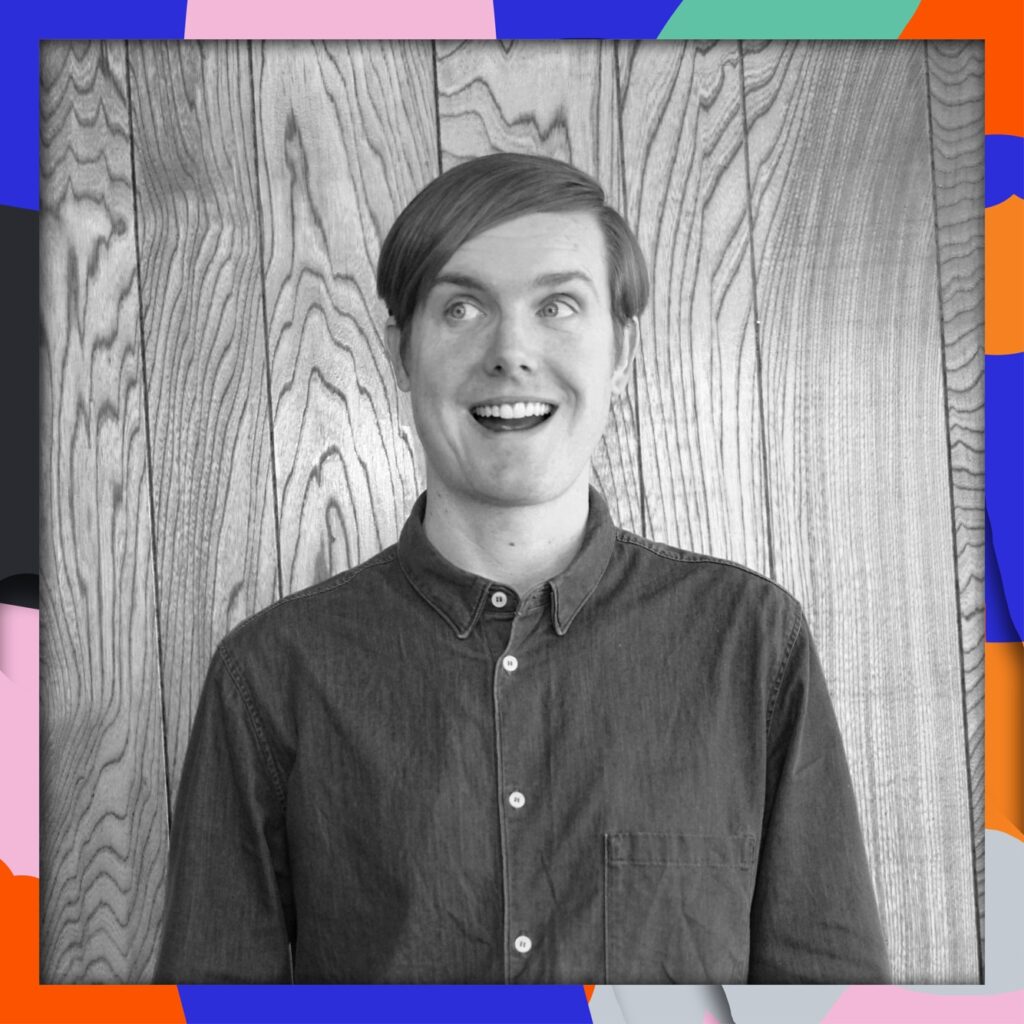

Mark “Frosty” McNeill, who is the co-founder of the Los Angeles-based internet radio station dublab, which has a global listenership, discovered Rei Harakami’s music as it was being released while Harakami was alive and has also shared the stage with him as a DJ. Frosty is also known as a curator on the Pacific Breeze: Japanese City Pop, AOR And Boogie 1976-1986, Pacific Breeze 2: Japanese City Pop, AOR And Boogie 1972-1986, and Somewhere Between: Mutant Pop, Electronic Minimalism & Shadow Sounds Of Japan 1980-1988 compilations. As someone who has his finger on the pulse for international music and an ardent fan of Japanese music, we asked him about his thoughts on Rei Harakami and why Harakami’s music has attracted listeners from around the world.

――When was the first time you heard Rei Harakami’s music, and what were the circumstances? How did it make you feel when you first heard his music?

Frosty: I actually can’t put my finger on the first time I heard Rei’s music, rather it seemed like something that slowly faded into existence. His music entered my sphere like the humming of the atmosphere before solidifying into recognition. This revelation is actually much more satisfying as it was an evolution of awareness, and for me, this fits the character of Rei Harakami’s sounds. Once they slid into my consciousness, I realized that my library was already well stocked with his music and that I had even played it on the radio prior, possibly in a state of Harakami-hypnosis. I’m sure I stood in front of a listening station at Spiral Records decades ago with headphones on, wrapped in the wonder of his work as the buzzing Tokyo life swirled around me as if in another universe. Once the light truly came on, the details of Rei’s individual compositions and body of work started to focus further—yet, still to this day, they retain an ephemeral quality as if hovering in a dreamstate just on the edge of possibility—almost too luminous to be real.

――You have been DJing at various events and have been active as a radio DJ with dublab for many years. Have you ever played Rei Harakami’s music as a DJ? Do you remember anything from playing his music out?

Frosty: Yes, I have definitely played Rei’s music a lot over the years: on the radio, at gigs, on curated playlists, at art happenings, but most of all in my home. His work has a really unique vibe—when I hear it, I know it’s Rei Harakami but it’s also like a sonic shapeshifter. His music has a fluid sort of sound that seems to harmonize to the call of manifold moments.

——When Carlos Niño performed in Japan (in 2010 at Tokyo Unit), Rei Harakami also performed there, and you opened up as a DJ. What do you remember from seeing his performance?

Frosty: I was completely awestruck by this experience. First off, I remember speaking with Rei Harakami backstage and was so impressed with his warm spirit. When he played, the venue’s already incredible sound system seemed to morph into some sort of spatial super system. It was as if we were immersed in a planetarium of sound—Harakami’s tones, the constellations beckoning us into new worlds. His performance was so gracefully elemental, as if his every sound emerged more so to give structure to silence and space, guideposts generously guiding us through the listening experience. It was like my brain and body had been recalibrated to experience the wonders of the world anew. When I showered him with well-deserved compliments after his set, it seemed like his humility only expanded—a peaceful attitude suggesting the music he played had always been there and he was simply gesturing at its essence.

The reason why I was attracted to Japanese music. The uniqueness of Rei Harakami

――When you started dublab (I think around 1999) you came to Japan. I met you for the first time back then, and I was surprised about how much you knew about Japanese indie music. How did you get interested in Japanese music?

Frosty: Wow, we have known each other for such a long time and I count myself a lucky person for that! Since I got involved in radio in 1994 at the University of Southern California my insatiable curiosity about the music of our wondrous world has accelerated, and when I founded dublab in 1999, it only went into overdrive. But my love for Japanese music dates back much further. My mother had an album of Japanese shakuhachi music on the Nonsesuch Explorer Series called A Bell Ringing in the Empty Sky. As a child, I would sit and listen to this for hours on end while staring at the intricate line drawings on the cover. It was as if a fantasy had manifested itself in the disc and years later when I first saw Akira Kurosawa’s film Dreams it felt like I had found an emotional equivalent to this. My thirst to experience more of this inspired creativity expanded and I started searching for Japanese music in earnest. Around 1999, when I found a copy of Cappablack’s The Opposition EP on Soup-Disk in the record bins of the mythical Aron’s Records, my flare was brightly lit and the quest for even more Japanese sounds was on.

――You must have listened to a lot of music from Japan that was of the same era as Rei Harakami. What made his music unique?

Frosty: Yes, I sure did. In college and into the early years of dublab, DJ Krush, Nobukazu Takemura, Susumu Yokota, and more were big for me and I still love this music while continuing to expand my breadth of Japanese music enjoyment. Rei’s music stood out in that it was like water sitting so crystalline in a glass on a windowsill with light pouring through the vessel projecting something altogether new on the other side. Upon lifting it to quench my thirst, I don’t long for the light that once was, but rather savor the simple glass’ many ways of giving nourishment. Listening now to Rei Harakami’s music as I write this, I feel a sense of natsukashii—I’m at once missing the past, like Rei’s 2010 concert at Tokyo Unit, while reveling in the joy his music brings me in the present moment.

――Rei was active between 1998 and 2011. He was part of the electronic music scene during this time, but what did his music achieve in the worldwide electronic scene?

Frosty: This is a hard question and I’m just grasping at my own perception. I feel like Rei Harakami’s music is still so under-appreciated, which is not necessarily a bad thing because the people who are fortunate enough to encounter it will value it even more. Many artists are not recognized in their time because our minds and souls need to move into a state where we can truly understand the value of their work. With Harakami, I feel like his music is timeless in nature and in our world of constant chaos it is a sanctuary, that once-discovered, brings great solace.

――Rei Harakami was influenced by music other than electronic music, but what type of influences do you feel from his music?

Frosty: More so than the influence of other music, when I listen to Harakami’s work, I get the sense that he was captivated by the magic of our world, the fleeting wonders that are only recognized by the eyes of the perceiver and thereby cherished as intangible elements that when summed make us human.

――It seems that a lot of overseas music fans are taking an interest in Harakami’s music, but what is it that draws them to his music?

Frosty: Music is so subjective and we are ever-changing from moment to moment so it’s hard to guess what others are feeling but I can only imagine that his music serves as a balm to the chaos.

――Harakami’s “Hiroi Sekai To Semai Sekai” is a collection of his music before his official debut, but what were your thoughts on this album?

Frosty: I am so thrilled by this release. It’s still so new to me and I anticipate spending much time with this music in the years to come. Hearing Rei Harakami’s early works is like finding more to love. I can hear the great joy, enthusiasm, and humor that went into making these works. Rei’s later works are also enriched by this early view—reflections of his personality are colored through this wider lens.

The impact of the introduction of Japanese city pop on the U.S. music scene. Notable artists after Rei Harakami.

――You worked on the Pacific Breeze compilation that brought city pop to overseas listeners, which is an era of music before Harakami’s time, but do you see any similarities or differences?

Frosty: I think that we live in a world of wide possibilities yet our collective potential is dampened by the narrow streams we are fed through mainstream media and marketing. Most of the world listens to a miniscule body of work while conversely the majority of music made, only ever reaches a minority of people. My life’s mission is to reverse this trend and share underrepresented, creative music with the world. Our human minds have great potential to expand and music is one great way to stretch them. So much amazing music has come from Japan and it’s a shame when it ends at the country’s shores, so I’ve been thrilled to see more folks enjoying Japanese music and have been thankful to do my small part to share it.

――How has city pop influenced the US music scene? Has there been more interest in music from Japan?

Frosty: I went into a record store the other day for the first time in a long while and the Japanese bin was really well stocked but each album was easily three to four times the cost of the other records in the store. While this shows the high interest, it also illustrates that demand can decrease access. I hope that the price bubble pops a bit in the vintage record selling market and that music is once again made more accessible. Sure, we have streaming services but there is so much great music out there that’s not on these platforms, but physical media shouldn’t come at a cost that forces consumers to choose from eating or listening. That’s one of the reasons I have been excited to work with Light in the Attic Records to produce compilations of Japanese music like the Pacific Breeze series and the Somewhere Between compilation. We’re sifting through mountains of music in order to provide thoughtfully crafted collections of jewels for the public to hear at a reasonable rate.

――Has there been any music after Harakami from Japan that you are interested in? If there are any artists you have your eye on please let us know.

Frosty: I’m loving what Foodman is up to, H. Takahashi always amazes me, Chee Shimizu is the key to so much, Kuniyuki Takahashi is a sublime sureshot, Meitei is excavating and illuminating, Ytamo and Oorutaichi are my lights, Kenji Kihara keeps me grounded, and Midori Takada is like an eclipse that stays perfectly in balance.

――If Harakami were still alive, how do you think he might have influenced the current scene?

Frosty: Rei Harakami would have continued to make music true to his heart. This pure act would likely have influenced many others to follow their passions.

――What are your top 10 Rei Harakami tunes?

Rei Harakami – after joy

Rei Harakami – sequence_01

Rei Harakami with Ikuko Harada – sequence_03

Rei Harakami – unexpected situations

Rei Harakami – remain

Rei Harakami – double flat

Rei Harakami – on

Rei Harakami – a certain theme

Rei Harakami – owari no kisetsu

Rei Harakami – くそがらす (plus more favorites to come from Hiroi Sekai To Semai Sekai!)

Mark “Frosty” McNeill is a DJ, radio producer, curator, university professor, and Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker based in Los Angeles. He’s the founder of dublab.com, a pioneering web radio station that has been exploring wide-spectrum music since 1999. McNeill hosts weekly radio shows for dublab. As Adventure Time, he and Daedelus have created new worlds of sound and alongside dublab colleagues he activates the Golden Hits dream machine. Frosty has performed high concept DJ sets around the globe with the mission of sharing transcendent sonic experiences.

Web: frosty.la

Radio: dublab.com/djs/frosty

Twitter: @dublabfrosty

Instagram: @dubfrosty

Translation Hashim Kotaro Bharoocha

Edit Takahiro Fujikawa