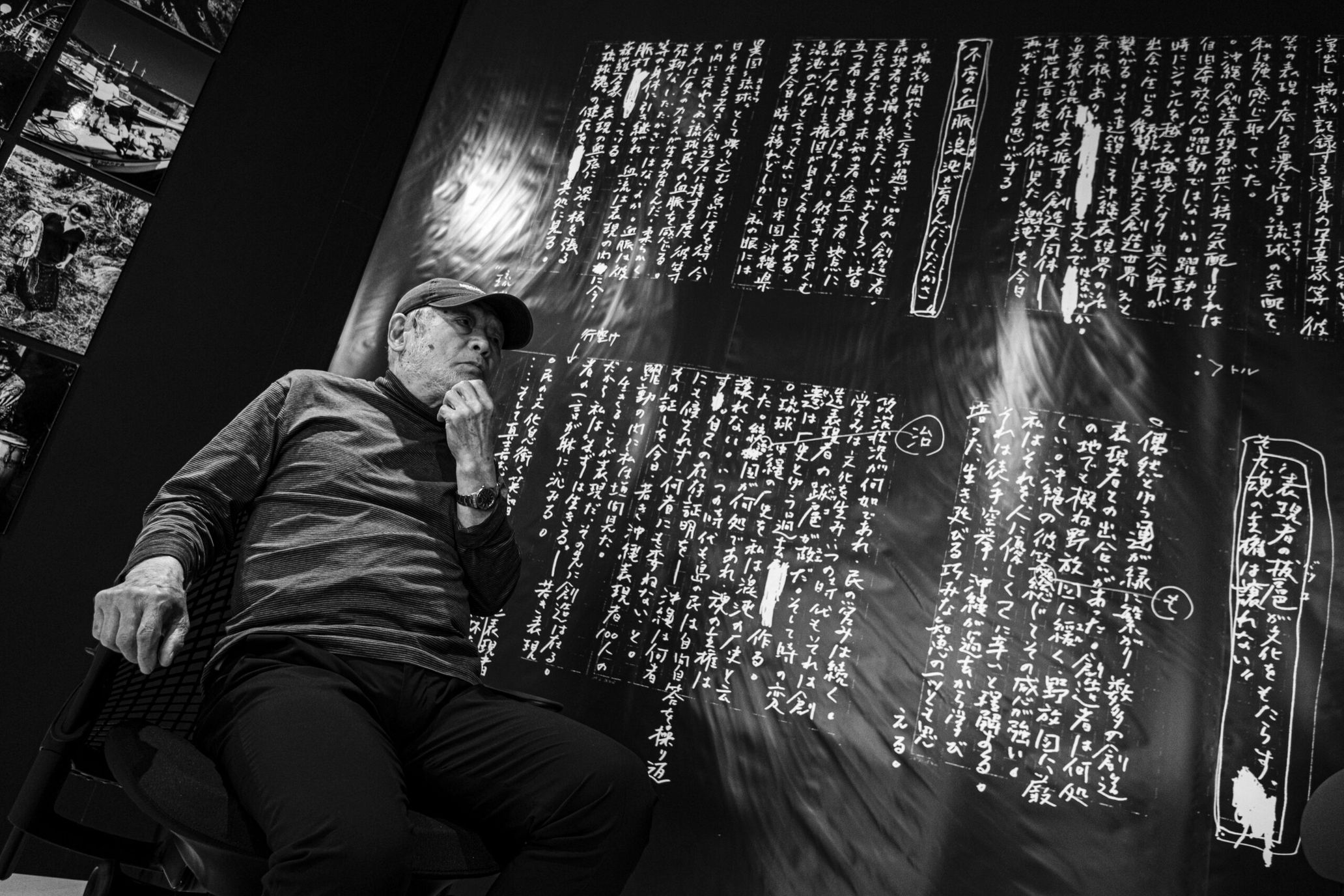

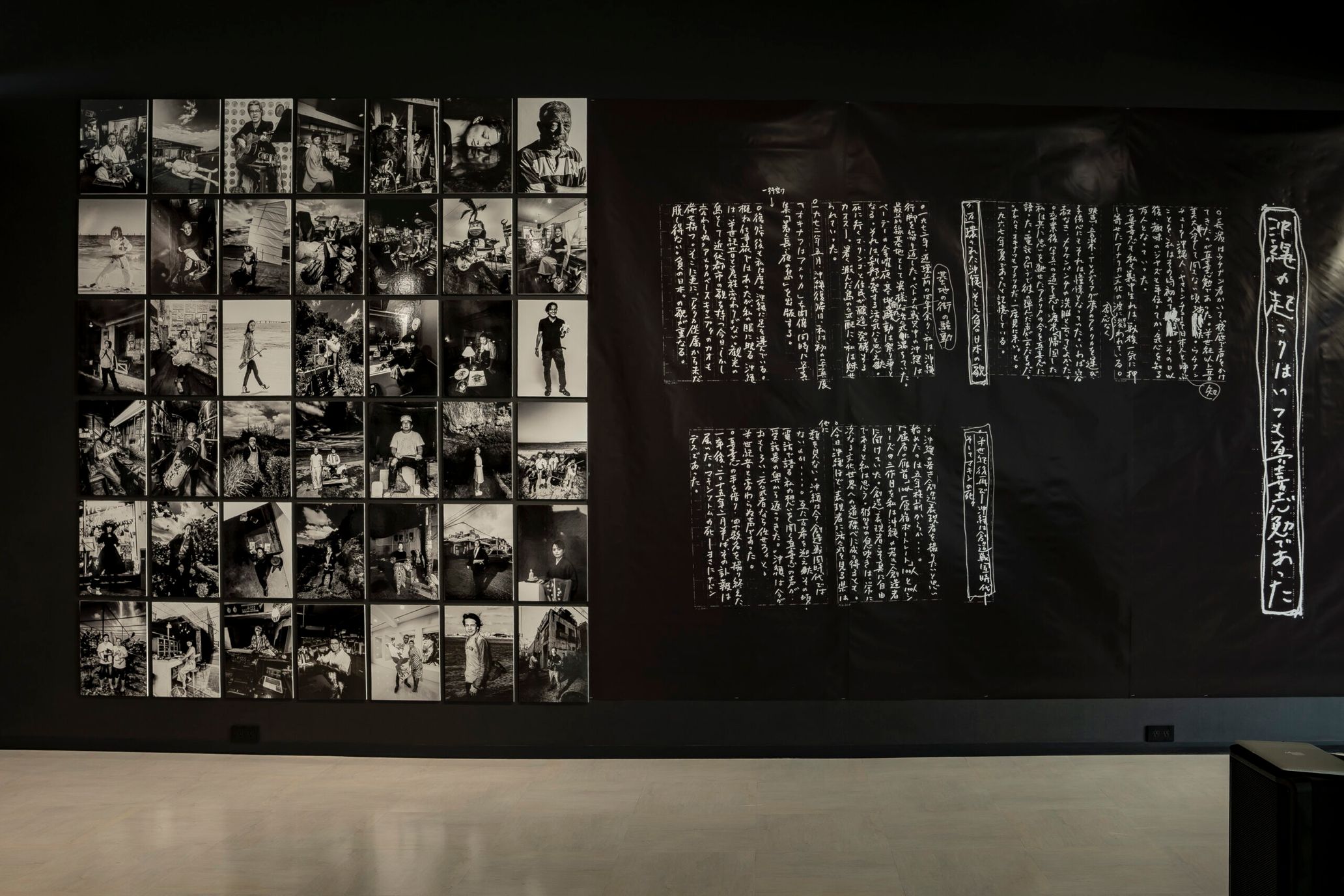

The exhibition 50th Anniversary of the Reversion of Okinawa to Japan, 1972-2022 TOMMAX and Osamu Nagahama: Two Men’s Okinawa and America, presented by PLAZA HOUSE x MOON HOTELS & RESORTS, was held in Okinawa for about a month beginning on May 15, 2022, the 50th anniversary of Okinawa’s reversion to Japan.

In this exhibition, the two artists who were both born in 1941 and experienced Japan’s war years expressed what they had gone through in Okinawa and the U.S. through black-and-white photographs and other artworks. Their body of work, where the lives of two artists who’ve lived through the same era and work on the same wavelength intersects, is socially conscious, emitting a positive energy while containing a darkness within. In the exhibition hall, their favorite music, such as jazz and blues, was playing.

This two-part interview explores the content of the exhibition and the encounter between the two artists through Osamu Nagahama’s voice. In this first part, Nagahama reveals how the two met and how he built his own career as a photographer.

Osamu Nagahama

Born in Nagoya in 1941, Nagahama first worked for an advertising production company after graduating from the sculpture department of Tama Art University. After working as an assistant to the photographer Yoshihiro Tatsuki, he became a freelance photographer in 1966. He has been active in the fields of fashion, advertising, and portraiture, while mainly photographing overseas rock festivals and counterculture. He has also photographed bikers in New York, blues musicians in the southern United States, Japanese men at the forefront of their respective industries, and the Okinawa n people over the years. He is also known for his close relationship with the fashion brand NEIGHBORHOOD. His major works include 暑く長い夜の島 —長濱 治 沖縄写真集 (The Island of the Long Hot Night: 1972), HELL’S ANGELS (1981), 猛者の雁首 (The Faces of Strong Men: 2005), THE TOKYO HUNDREDS: A Portrait of Harajuku (2014), 創造する魂 沖縄ギラギラ琉球キラキラ 100+2 (The Soul of Creation: Okinawa Gira Gira Ryukyu Kira Kira 100+2 :2018), and Cotton Fields (2018).

Hitting it off through music

――First of all, please tell us how the two of you met.

Osamu Nagahama (Nagahama): Makishi and I were born at the beginning of the war. Although the immediate situation surrounding each of us was different, the war ended on August 15, 1945. After that, Japan went through the postwar period under the direction of the U.S. Occupation Forces, and although the physical distance between Nagoya, where I was born, and main island of Okinawa was great, the social situation was the same. In other words, both of us experienced the same culture imported from the U.S.. Even as children, we were sensitive to this, and the American culture was imprinted on us.

Putting aside the details, I met Makishi by chance while attending art college. He told me “Nagahama” was a common name in Okinawa. We got to talking after that, and it turned out that he liked jazz, blues, and rakugo. We became friends because we had many interests in common. I guess it would be more accurate to say that we became friends through jazz, or rather, through the perfect American music. In art school, he was painting and I was sculpting.

――Who were your favorite jazz musicians?

Nagahama: When I was in elementary school, I started out with swing and bebop, and became fascinated with artists like Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, [Alton] Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. When I entered junior high school, I became a big fan of the so-called modern jazz of the late ‘50s bebop era. High school was nothing but modern jazz for me. In college, I went to see the MJQ [Modern Jazz Quartet] live, and Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers at Sankei Hall. It was very exciting. At that time, I went to see about 60% of the artists who came to Japan, like Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan and Dexter Gorton. When all those musicians were coming to Japan, Makishi and I were like, “Let’s go!!”

――So your taste matched Makiishi’s perfectly?

Nagahama: At that time, there were not many students who liked jazz or rakugo, and I wasn’t really able to share those interests with anyone but Makishi. Although we were good friends, he went back to Okinawa after graduation, and I began a career as a photographer. A few years later, in 1966, I took my first boat trip to the United States. And when I came back to Japan six months later, I talked to Makishi on the phone while he was in Okinawa.

The impact of of American bikers in the 1970s

――Next, please tell us about your career in photography. What was your time as a photographer like when you went to the U.S. in 1966?

Nagahama: When I went, it was a time when the hippie and anti-war movements were happening all around the country. Especially in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood and the Berkeley area, flower children were holding anti-war demonstrations all year round. It was at the height of the Vietnam War. I witnessed the so-called psychedelic culture, but I wasn’t really shocked or stimulated by it. I don’t know how to put it, it was like a kind of festival, I didn’t feel anything was in earnest. […] The students who went to school in the Berkeley area were the sons and daughters of the wealthy, and all of them were well-to-do. So the anti-war social movements were probably a movement for new values, but I didn’t feel their power of conviction or anything like that. It was interesting to see how they used fashion and drugs to express themselves in various ways, but it didn’t strike a chord with me. I was not moved by it.

Later, I had an unforgettable moment at Fillmore West. It was the time when heavy rock bands like Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe and the Fish, the Grateful Dead, and The Who were coming out. So the day that the Grateful Dead played, I went there with my camera and came across these huge motorcycles. I thought they were amazing, and as I was wandering around the bikes, I saw a huge group of people coming out from the bar. That group was the Hell’s Angels.

――So that was your first encounter with the legendary Hell’s Angels?

Nagahama: Yes. They were the polar opposites of young wealthy revelers. At that moment, I thought, “I have to take pictures of them!” But then a Berkeley student who was with me said, “No. Don’t take any pictures, or you’ll be killed!” So I couldn’t do it.

I got interested in them and did a lot of research after I returned to Japan. At that time, there were no documents about them available, so I didn’t even know Hunter S. Thompson, whose work covered the Hell’s Angels. I talked to an acquaintance who was working for a New York-based publishing company at the time, and he told me that there were young ferocious bikers like that in New York as well.

I had a book at the time, Love on the Left Bank by Ed van der Elsken, which had motivated me to become a photographer, and I wanted to make a book that would be as great as that one. So I chose the Hell’s Angels as my subject. I focused on a group of young people who were American, dispossessed, and unbacked by the kind of wealth that hippies had. Another important point was that they were based in urban areas. New York is a big city, and they were the perfect target group, so I flew right over. That’s where I found the Nomad New York Aliens, a group of motorcyclists.

――They were the group later featured in your photobook, right?

Nagahama: For those who like them, they’re legendary. A couple of years later, they became the New York Hell’s Angels. But I liked the Aliens better. They had gangsterism, but also a purity, a sense of goodness, or justice. They were poor, but they had a kind of rebellious and youthful spirit. So even though they were bad, riding their motorcycles and getting into fights, they never took anyone’s life. They were, in a way, smart.

I started taking pictures of them in 1969, and I think the last time I photographed them was in 1979. That’s not to say that I was photographing them for 10 years straight. But whenever I had a chance to go to the U.S. and somewhere near New York, I always visited and took photos of them. As their name “nomad” implied, though, they were never at one base, always somewhere else. They were literally nomads, that’s why I thought they were cool. So I’d go to their camp in New York to say “Hey, long time no see,” and start taking photographs. But then before I knew it, they came to be called the New York Hell’s Angels. I couldn’t judge if that was a good thing or not. To me, they’re still the Nomad Aliens.

TOMMAX’s invitation: “Look at the America in Okinawa!”

――While you were in the midst of your project shooting bikers in New York, you also visited Okinawa, right?

Nagahama: Yes. When I was talking with Makishi about those bikers, he said, “That’s not all. Look at the America in Okinawa, too!” That’s when I started going to Okinawa as well, shooting both the Angels and Okinawa at the same time. Then after Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972, Makishi also started to going to New York. That’s why we were in the U.S. at the same time. So I’ve included photos from that period in the exhibition.

――I see. Although the photos were taken in different places, the historical backgrounds and atmospheres seem close. They all fit together nicely.

Nagahama: Yeah, they were all connected. I took the pictures in Okinawa and pictures of the bikers in New York at around the same time in 1969. After taking photos between Okinawa and in New York, I came back to Japan to work intensely. And when I had enough money, I went back again. I had no sponsors, so I did everything on my own.

――What was Okinawa like in 1969 when it was still part of the U.S.?

Nagahama: Naha Airport was much smaller than it is now, and when you got off the plane, you had to go through immigration and show your passport. It was completely a different country. And when the people [in immigration] saw “Nagahama” on my passport, they asked me if I was from Okinawa. It was a military airport, so military planes and military vehicles were parked at the end of the airfield. This was when the U.S. was still fighting in the Vietnam War.

――Right, in 1969 they were still in the middle of the Vietnam War. At around the same time, you went to Koza City [now Okinawa City] to take photographs, is that right?

Nagahama: That’s right. The city was full of soldiers. I photographed the soldiers, the girls who flocked to the bars where the soldiers gathered, and the brothels.

――This exhibition opened on May 15, which is also the 50th anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa to Japan. What did you think of Okinawa 50 years ago?

Nagahama: Whatever feelings I had, I have always seen Okinawa through Makishi. As for the U.S., I had my own interests, but for Okinawa, Makishi was the catalyst.

Okinawa used to be Ryukyu. I don’t know exactly what the Ryukyu Kingdom was like, but I know the basics. Although it was a small island nation, the Ryukyu dynasty lasted some 450 years. Then it became a U.S. territory, then Japanese. So I was happy that Okinawa was returned to Japan from the U.S., but at the time I couldn’t think that deeply about it. I thought that the Ryukyu Kingdom should have carried on as it once had.

Capturing the Ryukyu pride of the Okinawan people through photographs

――What do you mean when you say that the “Ryukyu Kingdom should have carried on as it once had?”

Nagahama: I mean, I wonder what would have happened if that place had been able to value something like Ryukyu spirits, instead of letting it become “Okinawa” again. The Japanese system of governance is fine, but if the culture had been nurtured in a different way, it could have become a very interesting country.

――I see. I felt that you were looking at Okinawa through Makishi, but I didn’t realize you were also looking at the Ryukyu Kingdom.

Nagahama: I have always been somewhat cautious about using the word “Ryukyu,” and although I felt it would be inappropriate to do so, I did use it in a photo book. It was called 創造する魂 沖縄ギラギラ琉球キラキラ100+2 (The Soul of Creation: Okinawa Gira Gira Ryukyu Kira Kira 100+2). Of course, some would say, “This isn’t Ryukyu anymore!” But as I continued to take photographs, I felt that there were many people who were interested in Ryukyu.

――When I spoke to you before, I was impressed by the fact that you said Okinawa was your long-term photographic subject. So that sense of process went into the photobook, too, right?

Nagahama: Yes. I felt that I had to record the existence of positive young people in Okinawa once again. When I was talking with Makishi about this, he looked really unusually happy and said, “We’re building an amazing museum [in Okinawa] right now!” He told me there were all these young and talented artists in Okinawa. I had this idea in mind where I wanted to take photos of a hundred different people, so I asked him, “Hey, can you gather a hundred people?” He said, “Leave it to me.” So we began shooting, but then before we made it back to Okinawa for a second time, Makishi passed away.

――When you were photographing the people of Okinawa, did you feel a particular Okinawan element within them?

Nagahama: What they had in common was that they all had their eyes set on Okinawa. They didn’t look to the Tokyo area at all. I had felt that since I first came to Okinawa in the 60s. When I listened to young people, I could tell they were looking at Asia, China and the U.S.. I don’t think anyone mentioned Tokyo. In other words, I think a sense of independence is in their blood.

――What kind of person was Makishi from your point of view?

Nagahama: Makishi was every bit the person you could see. He had Ryukyuan blood in him. He was a generous, big, good-looking man with dark skin. And to put it in a cool way, he was never one to follow a crowd. I think that’s why we were able to get along. I don’t have such a strong disposition, I often want to talk to people and ask questions, but lived in his own unique world. And by big, I mean big in body and big in mind. His works were cool and edgy. The inspiration of music ran through both of us. We hit it off through jazz and blues.

When Makishi worked, he would put up several large canvases in a square and paint with an audience. Jazz players he knew would gather and he painted while they played. He was creating a unique space in Okinawa, and I think he was creating an academic world.

A single camera opens the door to another world

――Why do you shoot in black and white?

Nagahama: I think the foundation of photography is monochrome, and I don’t like color because it adds too much unnecessary explanation. Photography, in my mind, is the grainy black-and-white photographs that I’ve seen since I was a child. And I like intense black-and-white tones. That may be partly because I used to do sculpture. I was a sculptor as a student, so I also show three dimensions in my photographs.

――Why do you think you have continued to take photographs?

Nagahama: It’s nothing so complicated. When I wake up in the morning, I turn to the right and see my wife, which makes me feel at ease. And then I look to the left, and see a camera. I think, “Today, too, I will live with this wife and this camera.” That’s about it. It’s not about keeping on taking pictures or anything. But I am very happy to be able to make a living with just one camera. And that makes me like photography. I felt that recently. Before, I wouldn’t say that I liked or disliked photography. But the moment I held the camera in my hands, I felt that the weight and the feel of the camera fit me very well. It ended up expanding my world. It took me around the world, and then it took me to all kinds of mundane, everyday situations. If I didn’t have a camera, I’d just be another old man. [Laughs] I took all these pictures in my early days with this [NIKON camera]. This is the one that carried me all the way. It’s pretty amazing.