Heavenphetaminne was formed as a trio in Tokyo in 2018, but vocalist Hiroki and drummer Sara stopped living in Japan in 2021.

They moved their home base to Georgia, a country with a distinct culture between Europe and Asia. The two often play shows and go on tours abroad, trying to make a living through music in Georgia.

Hiroki and Sara, who say that talking is hard and playing music is easier, have rarely appeared in the media. They’re in the middle of a busy tour spanning 14 countries, mainly in Europe, and don’t even have time to post about it online.

They spoke to us in between shows to discuss their music career and ongoing charity tour, the NOM Project.

The reason behind moving abroad

–Why did you decide to leave Japan and move your home base to a foreign country?

Hiroki: I’ve toured in countries like New Zealand, the UK, and Australia with this band and my other one, Thatta, and the vibe of the audience and the way venues operate were so different from Japan. Everything was. Japanese people are shy, so they don’t jam out to a band they’re seeing live for the first time. But people in other countries dance like they’re having a blast when the band even slightly matches their taste. Grandmas with both arms covered in tattoos would dance and tell us how amazing we were. Some people hear our show from outside as they walk and would stop by. Live shows are an extension of people’s everyday lives, and it’s as though it’s deeply embedded in their culture. The more I experienced things like that, the more I began to want to go abroad.

Sara: Having one show [per city/country] while on tour wasn’t enough. We would make connections, only for them to end there and then. We wanted to go overseas regularly and create and maintain relationships.

Hiroki: Yeah. I had wanted to live abroad for a long time.

–Why did you choose Georgia?

Sara: I wanted to live in Melbourne, Australia, at first. People I befriended on tour told me they’d even help me look for a job. I was at an age where I could still go there on a working holiday visa. We were like, “This is great,” since he could also apply for a partner visa and stay in Australia for a little while. But covid hit right after I had applied for it, so we couldn’t go.

I looked for other countries I could stay in for an extended period, and the Netherlands came up. I asked a friend who ran a ramen restaurant there, and they said, “Things like taxes become pretty challenging from your second year.” They told me Georgia is an exciting place to make music because there are a lot of artists from other places. That was the first time I found out about the country. I was surprised to learn that you could stay there for a year without a visa. It was the perfect place because it’s easy to go to other European countries from there.

Hiroki: We went to Tbilisi, the capital, in September 2021 without knowing anything or anyone there. We felt like we’d make it work.

Planning on playing psychedelic punk in Melbourne, but ending up in Tbilisi

–What was it like once you got there?

Hiroki: As fate would have it, we met a Japanese person running a bar in Tbilisi who had lived there for a long time and were knowledgeable about the country. What they said shocked us: “You won’t really find indie rock or post-punk acts in Georgia.” I was like, “Oh no, what should we do?”

Sara: I had this image that Georgia had many live music venues like Japan, but that wasn’t the case. In Georgia, jazz, techno, and experimental music are popular, but they don’t have the culture of listening to live indie rock music. We were like, “Where are we going to play?”

Hiroki: The same person told us about an artist residency held during spring and summer called AqTushetii. They said, “Many artists and people interested in art will be there. It might be fun because they’ll also have workshops and performances.” We joined it and made some songs. That’s where we met someone who introduced us to venues where we could play live.

–So, there aren’t live music venues like those in Japan. What are the venues like in Georgia?

Hiroki: We mostly play in the corner of bars that host jazz bands. The stage is the kind where you go up one step, and that’s it. The acoustics aren’t as good as venues for live music, so the speakers are small, and you need to bring your own drums. The customers go to such bars to drink, not listen to music. They’re usually like, “The music sounds nice. I guess we can pay the cover charge and swing by.”

Also, it’s not like you play four or five songs per 30-minute set. In Georgia, they’re like, “Alright, we’ll leave tonight’s show in your hands.” You’d perform for an hour, rest for 30 minutes, then play for another hour. They’d be like, “You can do it, right?” and we’d be like, “No, we only have five songs” (laughs).

–How did you overcome that?

Hiroki: At first, we used to do covers, but we made new songs and memorized them quickly so we could play live shows. We made our shows longer, bit by bit. Georgians are used to jazz and techno, so we gradually incorporated more sounds and improvised sections, which is how each song became longer and longer. People in Japan prefer songs with clear verses, meaning we couldn’t spend three minutes playing the intro.

People in Georgia enjoy experimental or raw things. For instance, you would test products over and over until they’re complete before you start a business in Japan, but in Georgia, people would open up a store even if the interior is incomplete. I get inspired by that sort of laidback manner, in a good way.

Sara: I’ve always been bad at improvising on the spot. I used to run away at full speed whenever that was the direction things were going in. But since moving here, I’ve stopped thinking about useless things like, “I still don’t have the appropriate skill set.” I’ve started to think I can play what I want at each moment.

From being constrained to feeling confident enough to live abroad

–Is Japan no longer an option for you two? You couldn’t do what you do now in Japan?

Hiroki: No. We felt boxed in. It felt like nothing would come out of doing what we did in Japan.

I tried my best to make it big as a band back when there were five members in Thatta. We put out an EP, and Tower Records carried it in their stores nationwide. We even had our music video playing on Shibuya’s billboards. But the relationship between us bandmates became sour as we tried our best to become successful in our late 20s. Things became strained, and we couldn’t even talk to each other at the end. Other bands looked like they were in a good place from the outside looking in, but they also seemed like they were struggling.

Sara: People in Japan are too harsh on artists who don’t get a lot of press or are unknown. They say, “You’re still doing that?” or “I see you’re still chasing after your dreams.”

Hiroki: People mistakenly view art as chasing after one’s dreams. It’s just a way of living; it’s the same as working at a company. The only difference is I’m better at singing than doing business. People will accept you once you succeed, but there are many people like us. It’s a spectrum. Some of us aren’t mainstream enough to go on TV but are unique. It’d be better if such people could have the space to exist.

People in any country are unhappy about their government. There is a disparity between the rich and poor and discrimination too. Not much is different between Europe and Japan, but there’s still a playful spirit left in Europe. People try to preserve small, unkempt spaces. Many understand how boring the world would be if everyone only cared about making money. That’s why they place value on art.

–Do you feel less restrained compared to when you were in Japan?

Hiroki: After moving to Georgia, we’ve toured 14 countries, and many doors have opened for us. More people know about us, and the number of plays on our SoundCloud and Bandcamp is dozens more than the amount we accumulated over three to four years in Japan. We’re trying to put out music for more people now, so the breadth of possibilities is wider too. I feel our performances and name recognition will grow if we keep at it.

Sara: I feel like I can start living now. I’m learning how to do that.

Donating most of their savings to a friend in Ukraine, and a charity project that challenges capitalism

–Could you talk about the NOM Project, a tour you started this May?

Sara: NOM stands for “not only money.” This project started because Hiroki said, “Let’s donate all of our savings to our Ukrainian friend,” when the war between Russia and Ukraine broke out in February.

–All of your savings?

Sara: Yes. When he said, “Let’s start with donating one million yen,” I cried, saying, “No!”

–I understand that.

Hiroki: Before the war, we had a live show in Ukraine last December. We met people who let us stay at their place, and we hit it off. It was the first time I felt like a war was my own issue because people in a city I knew got caught up in war. I felt regretful for not realizing the absurdity of social constructs that lead to war much sooner.

When you get sucked up by capitalist systems in which growth is everything, it becomes normal to only think of yourself instead of others. When you talk about politics and the future in that way, abnormal things like war could happen normally.

Once the war broke out, I wanted to donate to our friend immediately, but I started comparing people’s lives with my day-to-day life. I was like, “How much should I donate?” The fact that I was on the fence was ridiculous. I started thinking that wars would always happen because of money.

Sara: Thanks to Hiroki’s suggestion, we kept the minimum money we needed for our lives and donated all of our savings to our Ukrainian friend. We then went on a tour and handed them our profits. That’s the NOM Project, which started in May. We go from place to place, mostly on land via bus or train, and sometimes hitchhiking around Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Serbia, and Ukraine. We try to be frugal, so many friends help us with accommodation and food.

Hiroki: Rather than making others pity us, we want to let go of our money and treat the act of thinking about money as an art piece. That’s our compensation.

–How did others react when you transferred the one million yen?

Sara: They thought we weren’t going to donate a lot of money, so they were shocked when we said we were donating one million yen.

–I bet. What is the money being used for?

Hiroki: We talk on the phone sometimes, and they’ve used the money to pay for a girl’s medical bills, as she got badly injured by a bomb. They’ve purchased night vision goggles and drones. They also share some of the money with neighbors who need help. They seem to use the money carefully in small amounts whenever necessary.

–I have this image of donations where it’s hard to imagine where the money’s going. It’s hard to feel like your money’s being put to good use, so it’s nice you donated directly to your friend.

Hiroki: We explain the mission of our project every time we perform live on tour to get donations, and people say things like, “It’s nice you can give money to someone on the ground since it’s speedy.”

Sara: So many people give us money and positive feelings. They tell us, “Hand this to your friend, yes?” Our show in Ukraine is coming up soon, so we’d like to be prepared to hand the money to our friend in person.

Searching for a way of life on the road

–Have your thoughts on money changed once you started donating money through the NOM Project?

Hiroki: All I did by saving money was buy a sense of security. Now that it’s gone, I can focus more on the present.

Sara: Before I started this project, I didn’t have a healthy relationship with money. I liked it, but I would lose sight of myself because I used to value it too much. I didn’t like how my mood would be influenced by how much money I got for a show. But now that we don’t have money and so many people support us, I no longer view it in an unpleasant light. I still don’t know what money means, though. You can say money is something you can exchange for what you need. It might be one medium to express feelings.

–Any closing statements?

Sara: We’re searching for a way of living by doing something good on tour. We play live almost daily and meet, talk to, and think with so many people. It’s exhausting but fun. People might not want to do this, but I want everyone to look deep inside their hearts. That might be the reason I drum.

Hiroki: I said this before, but we can now think of specific ways to improve because we continue doing what we do. I want to keep this project going instead of stopping now. Many people ask us whether we have a record, so next time we go on tour, I want to make one so people who’ve become fans can listen to our music.

Unless we change our values which prioritize money over helping others, a disastrous future awaits us. I hope this project can challenge things we take for granted. You don’t have to feel like you need to support what we do. If you take an interest in what we do and feel like watching us perform, that’s an accomplishment.

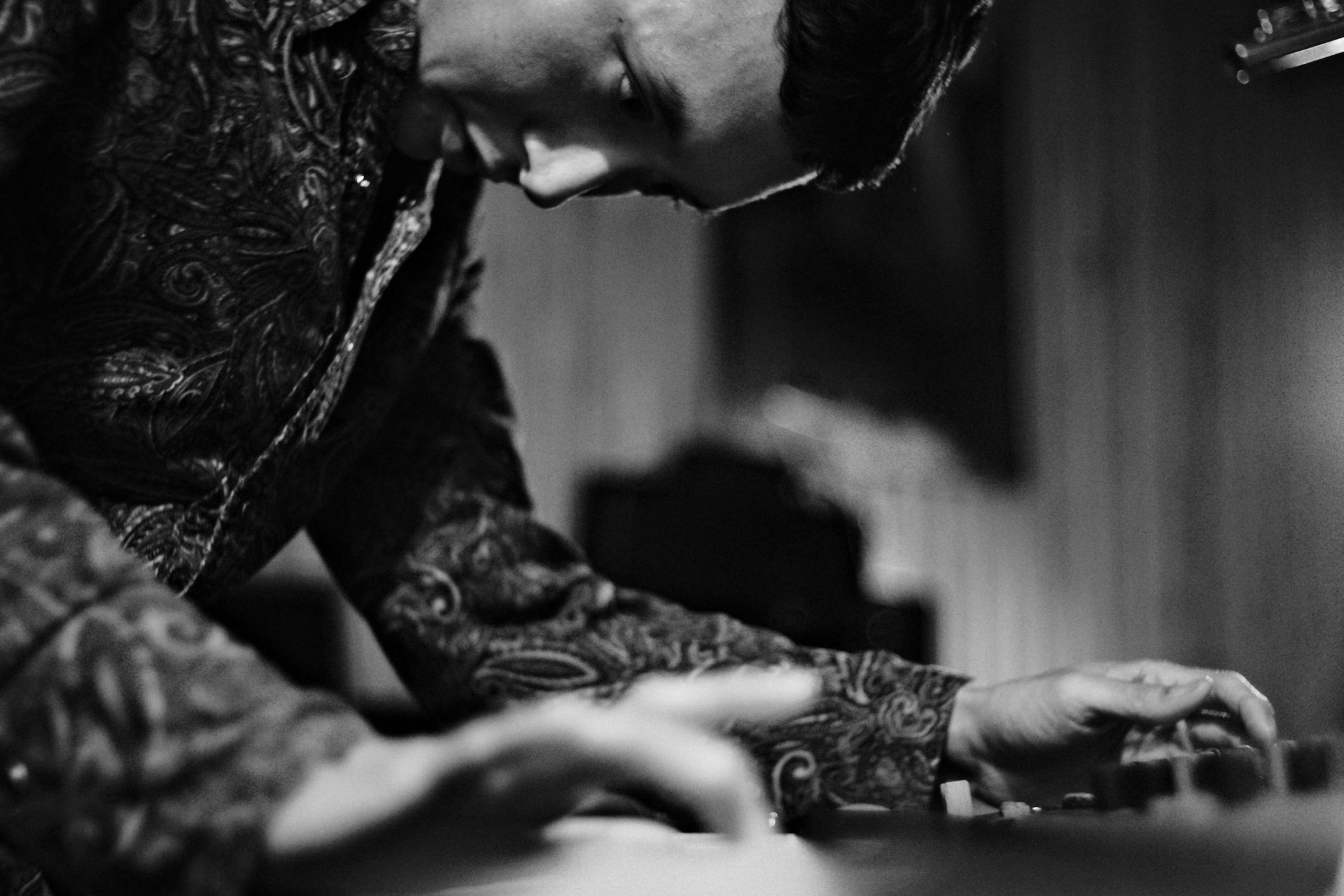

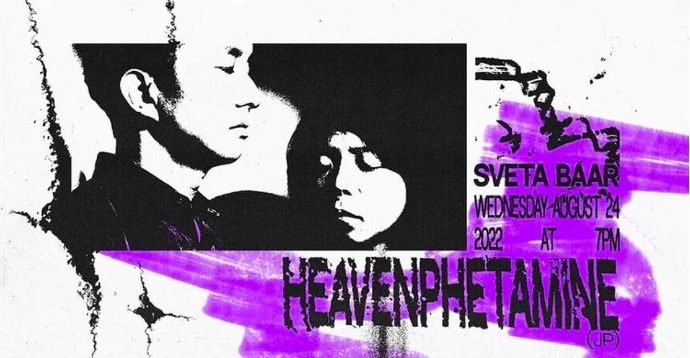

Heavenphetamine

Heavenphetamine was formed in Tokyo in 2018. They play live and go on tours primarily in Europe. The band consists of Hiroki on vocals and synthesizer and Sara on drums. Their unique style, a blend of a foundation of psychedelic rock, post-punk, new wave, and improvisational elements seen in jazz and techno, could be compared to various artists and bands such as Pink Floyd, The Who, LCD Soundsystem, Yosui Inoue, and Can.

Official website: https://heavenphetamine.studio.site/

Instagram: @heavenphetamine

Twitter: @heavenphetamine

YouTube: NOM by heavenphetamine

Photography Artur Byzenko、Takumi Yoshida

Translation Lena Grace Suda