Located on the Bond Street near Soho, New York, Dashwood Books is one block north of the house where Basquiat once lived and one block south of the late Robert Frank’s studio.

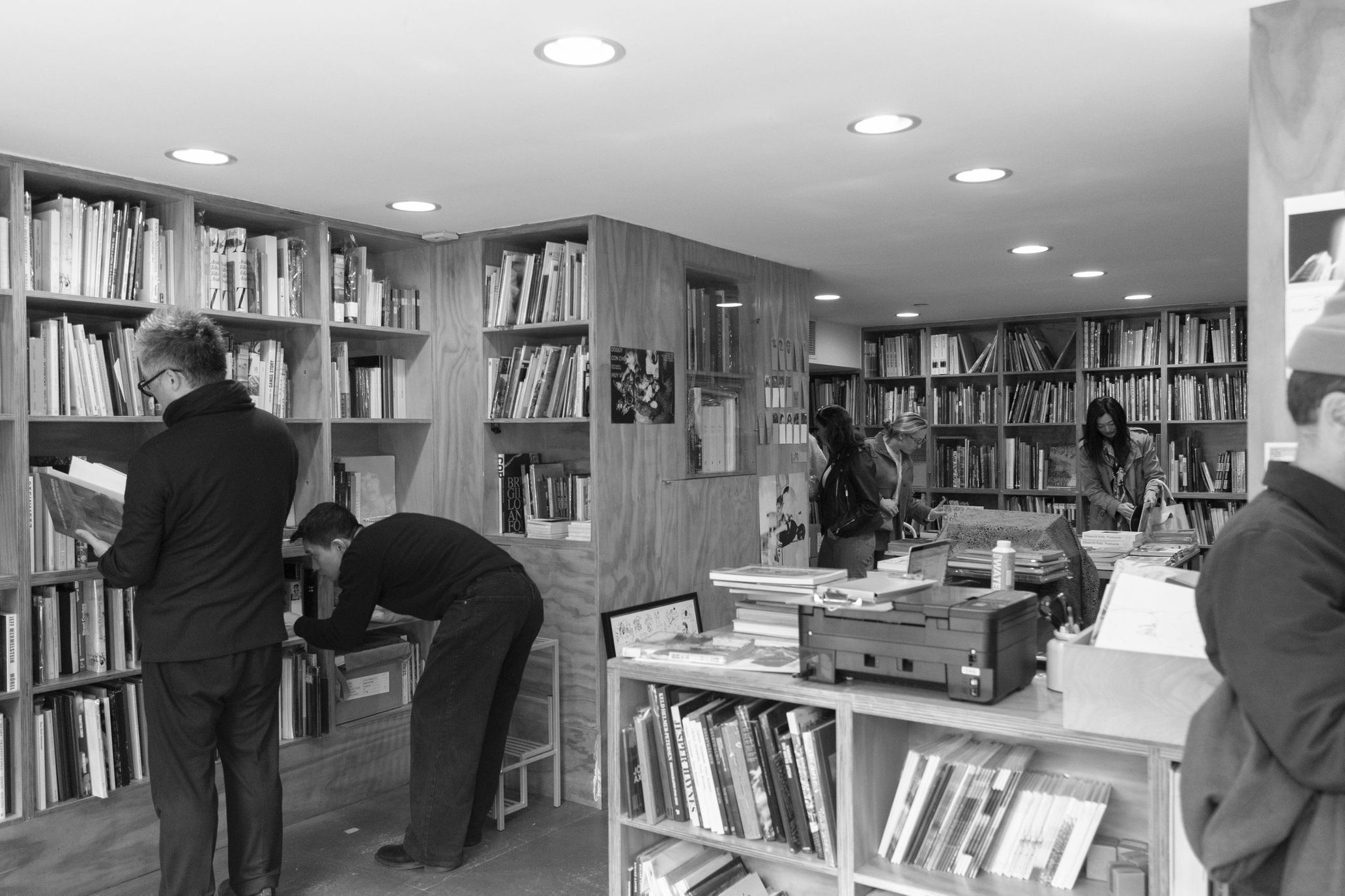

In the fast-changing New York, Dashwood Books has existed since 2005 with a consistent attitude as a bookstore specializing in photography books. When I visited the store, photographer Juergen Teller was in the store and Susuda was offering consultation to him. There was a tense dialogue going on between them, in which she used her knowledge and experience to understand the image Teller wanted to create and to propose a photobook that would help him expand upon his idea.

Later, Nick Sethi, a photographer who lives nearby, visited the store. A few days earlier, Dashwood Books had hosted a book signing for his book, to which many artists, including Peter Sutherland and Jason Nocito, came to celebrate the publication. The event was just full of people from all walks of life who came and went in the small semi-underground space.

What is the importance of physical stores, places, communities, and dialogues in a society where information technology has developed and many people prioritize their own convenience over others? Why does she continue to publish photobooks using analog methods?

As a manager of Dashwood Books since its establishment, Susuda has been involved in consulting and publishing with a focus on inspiring people’s hearts and minds. The conversation with her reminds us of the significance of capturing the essence precisely through substantial dialogues and passing it down to future generations.

Miwa Susuda

Susuda moved to the U.S. in 1995 and is a graduate of the State University of New York with a Master’s degree in Museum Studies. She has worked as an intern at the Japan Society, Asia Society, Brooklyn Museum, and Christie’s. Since 2006, she has been manager of Dashwood Books and director of Session Press, and has given lectures on contemporary Japanese photography at events like Visual Study Workshop. She also has contributed to various photography magazines and books in Japan and abroad, including IMA, in which she covers a variety of topics on the world of photography overseas. Since 2021, she has held workshops at the Penumbra Foundation in New York City, served as an advisor for the portfolio review at the photography course of Parsons School of Design in New York City, and was the jury of “The Paris Photo – Aperture Foundation Photography Award” in 2022.

https://www.dashwoodbooks.com

https://www.sessionpress.com

Instagram: @miwasusuda

As a “hub” for photography, Dashwood Books plays a central role in its capacity as a bookstore.

–Please tell us about how Dashwood Books was founded.

Miwa Susuda (Susuda): Dashwood Books was established in September 2005 in the Noho area of New York by David Strettell, who was the cultural director of the Magnum Photos.

He thought he wanted to concentrate on his photography consulting business, so he left Magnum. And before establishing the store, he happened to stop by a bookstore called On Sundays in Tokyo.

David originally thought that he needed a real place to do photography consulting, and when he came across On Sundays, he saw the potential in a bookstore with its sophisticated space and highly-specialized book selection.

David was considering various locations but decided to start the store on Bond Street, where it is now located, partly because he had lived in the East Village and partly through the introduction of a friend. This neighborhood was also home to Robert Frank’s studio and the houses where Mapplethorpe and Basquiat had lived, and these surroundings were probably important in establishing the store.

–When he established Dashwood Books, were there other independent bookstores specializing in photography books?

Susuda: Around the time Dashwood Books was established, photography was just beginning to attract people’s attention, and in New York City, galleries specializing in photography began to open in Chelsea in the early 2000s. Andrew Roth, a specialist in the history of photography, published The Book of 101 books, a sort of encyclopedia of photobooks, and more and more people were developing their interest in photography and photobook. However, there were few independent bookstores, and the majority of bookstores were large chains, so starting an independent bookstore specializing in photography was something very special.

There was a store in Soho that specialized in photography books called “Photographer’s Place (1979 – 2001)” that was particularly popular around 1990, but unfortunately it closed before Dashwood Books was established. So it is not that there were no independent bookstores at all; there was a climate in which photographers and creators seek out art books.

In New York, there have always been people who want to get inspiration from visuals, so there is an inevitable need for a place where they can share their interests.

–Was it that kind of characteristic of New York that made him believe the bookstore would be successful when he visited On Sundays?

Susuda: At first, he had no experience in retail and no knowledge of how to deal with customers, so he started the business fearfully with about half the space he has now. David is originally from England, so I think he tends to prefer edgy and unique things to major things, which might have something to do with a kind of Britishness. I think this attitude is based on a rebellious spirit against the blind belief that the majority is right and makes sense.

Therefore, our initial goal was not to sell anything like Amazon but to propose what we thought was good in a more professional way to people who would understand it, and I don’t think that has changed even now.

In the past, Photographer’s Place dealt mainly in works by well-known artists whose names were mentioned in museums and auction houses, such as Walker Evans, André Kertész, and Edward Weston. Accordingly, most of the collectors who flocked to that store were also conservative, preferring classic photography.

David, on the other hand, was looking for photographs that moved people even if they were a little outside of that sort of tradition or were memorable even if shocking in a way. Of course he also liked Kertész and Evans, but what made him very unique and ambitious was his focus on the contemporary rather than the established photographers.

–David’s consistent attitude has formed the personality of Dashwood Books, right?

Susuda: When I joined Dashwood Books, I thought David was a tastemaker. He always introduced what he thought was good with confidence, regardless of pre-existing evaluations, and that is what actually moved people. There are cases where photographers influenced by the books he introduced sometimes work on similar visual expressions in magazines or campaigns they are involved in, which makes me think that he is influencing the creations of major industries.

Another thing that Dashwood Books has always valued is to be a place for up-and-coming artists before fame comes to them. We have always actively supported these artists, even though they are often negatively associated with subcultures and the undergroundness. That’s why our collaborators as diverse as Gucci and the luxury hotel The Mercer trust David’s vision and are keen to work with him.

In this way, Dashwood Books is loved by people who are looking for something new, including corporations and fashion brands, because of David’s consistent attitude.

–When David started consulting on photography, what made him decide to do it through photobooks and bookstores rather than through galleries, for example?

Susuda: I think it was because bookstores can create a more democratic environment. I think Dashwood Books is an open place for creative people regardless of income level, from people who just reads books to wealthy people who can spend ten thousand dollars in a few minutes. The clientele includes artists, photographers, designers, academics, museum curators, and sometimes also trend-conscious young people.

If this place were to take the form of a gallery, it would only be able to introduce a limited type of artists with a certain degree of education, experience, and scarcity value that collectors would want to see. In addition, only those with plenty of money will have the opportunity to see the works, and this will limit the possibilities of communicating the great qualities of the works. I believe that art, by its very nature, is sometimes full of antithesis and avant-garde spirit, and is a means for those who have difficulty being accepted by society to express themselves. And there should be places that provide opportunities for people to come into contact with it. The best way to do that was through bookstores.

–Dashwood Books deals in books by Japanese photographers. How do you think they are perceived in New York?

Susuda: I think it is rare for bookstores in New York to actively sell and introduce photobooks by Japanese artists to clients in the U.S. and Europe.

Of course, there are stores in the U.S. and Europe that sell vintage Japanese photobooks, but David introduced books by artists who were not well known in New York at first, like Shinro Ohtake, for example, if he thought they were really good. I don’t think they would have been able to find Ohtake at an auction gallery or a bookstore that deals in Japanese photobooks from a commercial perspective.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, David used to visit Japan at least once a year to tour bookstores. Instead of perceiving photographs or photobooks based on history or information, he rather sees and understands them with his own eyes.

–What kind of place would you say Dashwood Books is?

Susuda: I feel that Dashwood Books is not only a bookstore in New York but also a place where people from all over the world who are fascinated by photography and photobooks come togather. As a center for photography, I think it plays as important a role as Paris Photo and the Aperture Foundation do.

When the pandemic broke out, many media outlets questioned the significance of physical stores, and many people left New York during the lockdown because they didn’t see the point of paying high rent in New York. Still, I believed in the necessity of physical stores, so I was very anxious during the period when I could not open the store, but I endured it patiently until the restart. And when the pandemic settled down and the store reopened, the creators who remained in New York immediately paid visits to the store.

The customers of Dashwood Books tend to be very interactive, so we need to communicate with them in a way that AI or Amazon can’t. I think the significance of a physical store is to be a place where we can share our expertise through dialogue, rather than just introducing books from a marketing perspective. There are many discoveries gained through conversation, and there are certain types of photos and photobooks that can only be encountered from a different perspective than marketing or AI.

Creativity is something that can turn 1 + 1 into 3 or 4, and I think it is often brought about by casual conversations and coincidences. A physical store can generate such dialogue. I think that is one of the charms of Dashwood Books.

In addition, Dashwood Books has staffs from various nations and backgrounds, including those from Mexico, France, and the United States. Although we are a small company, we feel that our diverse culture and the fact that we utilize our individual identities are important factors in attracting people to our store.

Staying close to people and conveying our worldview

–How did you start working at Dashwood Books?

Susuda: Before working at Dashwood Books, I worked at art museums and auction houses. Those experiences helped me figure out how I could survive in the New York art world. The three things I learned were to have a specialty, to work in a field where I could use 100% of my background, and to put myself in an environment that could complement those two things.

When I was a teenager, I set the goal of having my own position and job in the art world. I thought photography was the best choice because it has a shorter history than painting or sculpture, so I thought I would have a chance to do something new. On top of that, since Japanese photography is somewhat highly regarded overseas, I thought it would be best to specialize in photography as a Japanese working in New York. However, an environment that would back me up was something I hadn’t found yet back then.

At the time, it was impossible to find any top curator at museums, galleries, or auction houses who had a profound knowledge of photography by Japanese artists. While I was interning at the Bruce Silverstein Gallery in Chelsea, a gallery specializing in photography, the director happened to introduce me to David of Dashwood Books. Through working with David, I was able to understand his respect and love for Japanese photography, and I was convinced that Dashwood Books was an environment that fulfilled the three conditions mentioned above, so I decided to make my dream come true at this place.

–I think book consulting is one of the features that makes Dashwood Books very unique. Please tell us a bit about this.

Susuda: At Dashwood Books, we deal with photographs and photobooks, which we believe are works that move people’s hearts, so we think it is important to serve each customer in a way that we can build an ongoing relationship, rather than just selling books. I try to understand what they are looking for through conversations, and then suggest photobooks that will meet their expectations.

I have noticed that my background helps me a lot when I am doing book consulting. Japanese people are good at reading between the lines and the atmosphere, so I can communicate with people by imagining the meaning behind their words, rather than understanding them only on the surface. Instead of approaching customers in a logical manner, I stay close to them and make my suggestion based on the understanding of what is essential to their needs, and this is where I believe the power beyond the use of words comes into play.

–You have established a publishing house called “Session Press” to promote the works of Japanese and Asian photographers in New York. Please tell us about how you started it.

Susuda: There is a certain level of recognition in New York about the photographs and photobooks of Japanese artists such as Daido Moriyama and Eikoh Hosoe, but there is limited information about them. So I started Session Press, hoping that I could introduce them through publications.

For example, Mao Ishikawa, an Okinawan photographer, published a wonderful photobooks in the 1980s, but it is difficult to see them abroad because they are out of print. We published her book to let many people abroad know the sincerity, strength and brightness of her work, as well as the beauty of being one’s own self that her work appreciates.

We believe that a photobook, like an exhibition, can tell a story, and thus can itself be an opportunity to convey an artist’s worldview to a wider audience. I made books of Momo Okabe and Daisuke Yokota because I thought their photographs were truly wonderful, and I feel that I was able to help them gain recognition overseas.

Publishing is also a political statement for me. I have seen that Asians are not well recognized in the U.S., not only in art, but in other fields as well, and I continue to publish because I want to contribute to breaking the cycle of under-recognition. I feel that in the field of photobook publishing, Asian and Japanese backgrounds are fairly valued, so I hope to show the world the pride and creativity of Asian and Japanese people through our continued effort in publishing photobooks.

The significance of real stores, communities, and dialogue

–What do you think about having a real store and producing photobooks in a society where information technology has developed and images can be easily exchanged online?

Susuda: I feel that today, with the greater influence of social media and influencers, people tend to be just taking in information as it comes, and are less likely to experience and think about things on their own. Also, many people seek only what is convenient and efficient, or become too greedy. While marketing-oriented creations and promotions are understandable as a business model, the field of art should be more than that. If artists themselves and the buyers have only that kind of mindset, then I don’t think the true quality of the work can be conveyed.

I’m in charge of consulting work in Dashwood Books and also produce photobooks for Session Press, but I don’t think you can create something that moves people if you approach your work only in pursuit of efficiency. I place more emphasis on moving people’s hearts than on whether our publication sells well, so when I feel that someone’s work has the power to touch people’s hearts, even if it is outside the norm for society, I produce a photobook out of it with the hope of conveying that emotion. This is because I believe that what people remember in their hearts and minds is all about how they feel. What evokes our emotions is not accurate facts. A flesh-and-blood memory is synonymous with how much something resonates with each individual, and I think that is what art is all about.

I also feel that we have become overly sensitive to the voices of social media and the eyes of the public in many situations. There is a strong trend toward the idea of “modesty, righteousness, and grace,” which can be seen everywhere in all aspects of our life. As far as photography is concerned, even if it does not fit with the idea above, if it is something that moves people’s hearts, I am keen to put it out into the world. In other words, human beings are more complex, irrational, uncertain, and fragile, and I believe that sealing off such aspects of human nature is the opposite of what art should be about.

–Real places, physical things, and communication are all the more important because you are dealing with something that moves people’s hearts.

Susuda: Nan Goldin was very complimentary when I made Momo Okabe’s photobook, and Frank Ocean loved Mao Ishikawa’s book so much. I can get these reactions directly precisely because I produce photobooks and work in a real bookstore.

As something that can embody the artist’s worldview vividly, a photobook appeals to the viewer’s senses and fully evokes inspiration through the feel, the sound of turning the pages, the weight, and the smell of the printing and paper. As long as photographers exist, I believe photobooks will continue to exist.

Also in terms of music, I think that the emotion we feel when actually listening to live music is fundamentally different from that of listening to digital music. There are cases where digital is better, but if you truly want to understand something or be more moved by it, I think it is important to experience it first-hand.

My mission is to connect with people through photobooks as a platform, and of course, I want to fulfill this mission throughout my life, but I think it is too selfish to live as a person who thinks only about myself and narrows my own vision as if I shut myself behind a closed door. While it is a matter of course that I take care of myself, I want to never lose the most important spirit of humanity, which is to be considerate to others and attentive to what they are feeling.

–The production of your photobooks seems to be done through a very time-consuming process using analog methods, why do you choose to use these methodologies?

Susuda: I incorporate these methods partly as the antithesis of selfishness, but also because I believe that the analog method of production is the best way to move people. So no matter how much time and effort it takes, we make books very carefully.

In terms of Wing Shya’s book that we are currently working on, the artist shared about 2,000 photos with us, and we discuss many times to decide which images to use. Once the concept of the book is decided, we narrow down the images to be used and print about 500 images on paper to organize them. In the editing process, we make use of every part of the room, including the floor and walls. So my production process is totally different from the ones of other publishers, as most publishers these days use only a monitor screen to sort the images.

Once the general idea of the photobook is determined, I make a mock-up, which is the phase where I check how the book will actually look. Many things can only be understood through this process, so I always make several types of them. Through trial and error, the blueprint in the early stages of production evolves, leading to a better photobook.

Session Press is currently working on a book by Daido Moriyama and a Chinese photographer named Wing Shya. Wing Shya has been involved in photography and graphic design for film director Wong Kar-wai since the 1990s. While Christopher Doyle is best known for his visuals for Wong Kar-wai, Wing Shya has also made a significant contribution to his films as a location photographer, leaving behind many wonderful still images. He has also taken many snapshots, so we are working on the concept of Hong Kong in the 1990s as seen from his point of view. Now, Hong Kong is going through drastic changes. We are not particularly interested in creating something nostalgic because of that, but we hope that our work will somehow be supportive of what is going on there.

–At what point can you say that the photobook is completed?

Susuda: The production of a photobook is a collaboration between the photographer, designer, and myself. We select the appropriate designer for the book and photographer, and the three of us proceed through a series of careful discussions. I think it is complete when everyone is satisfied with the final product.

A photobook is not only about photographs, but also about printing, paper, design, and text. The important thing is not for someone to take the initiative, but for all three of us to respect each other and proceed in a balanced manner. However, we proceed with production, placing great importance on the photographer’s intentions as the most significant factor. Especially when it comes to design and texts, it is important to incorporate sensibilities outside of Japan and Asia in order to gain worldwide recognition. In that sense, we would like to create forms of expression where three parties generate a synergistic effect.

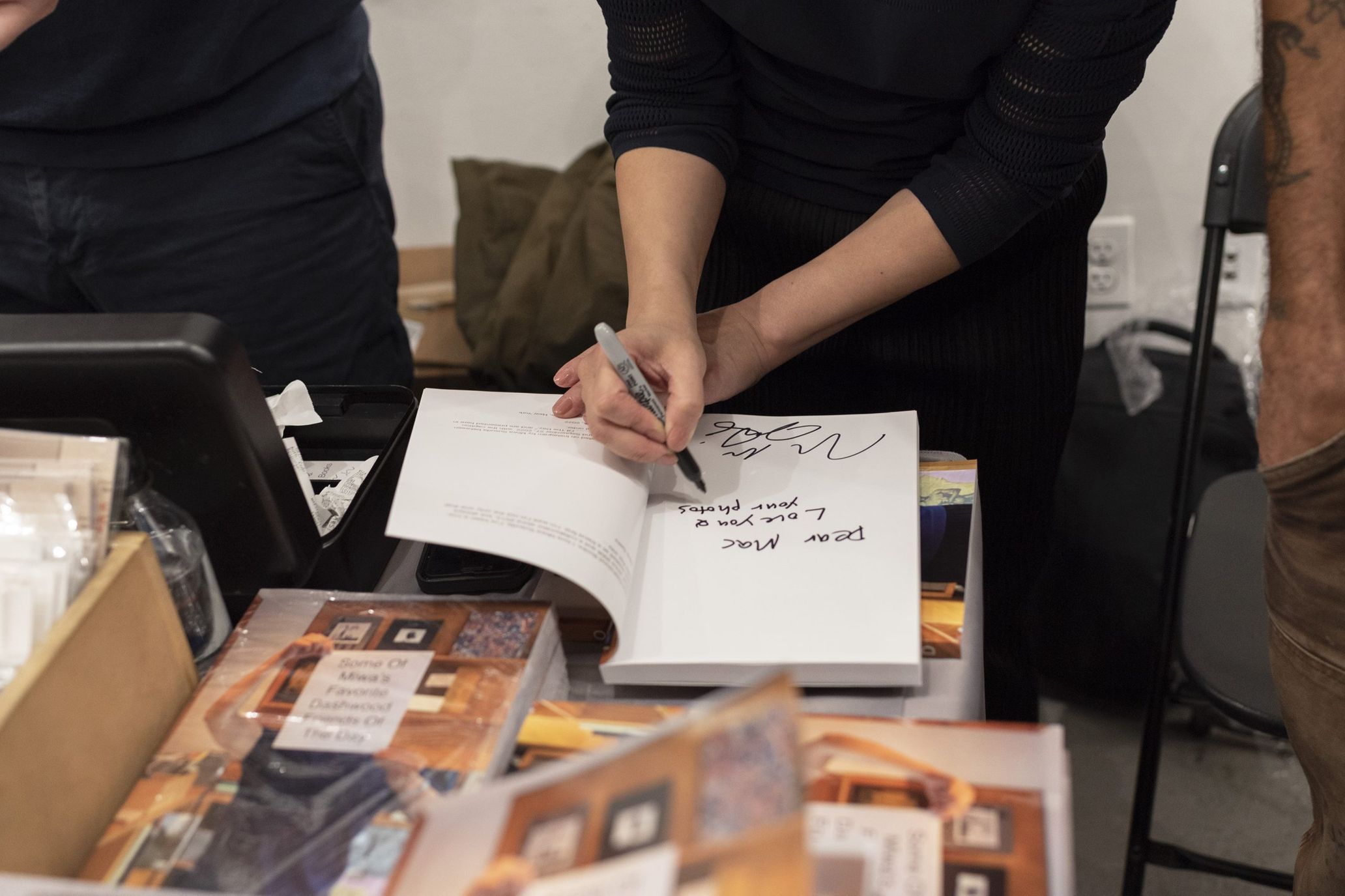

–Photographer Nick Sethi is producing a photobook with photographs of Dashwood Books’ customers for a publishing house he founded (*1). How did he come to publish this book?

Susuda: When Nick started the publishing house, he asked me if he could create a photobook using my Instagram photos. I was really surprised because I am not a photographer.

Nick has been coming to Dashwood Books since he was 18 years old, and I have watched him grow throughout the years, by dealing in his own zines at Dashwood Books. He truly appreciated the community that Dashwood Books and I have formed, and he wanted to make a photobook of them because he knew there must be many Dashwood Books customers who were feeling the same way. He even told me, “Dashwood is family to us.” So we appreciate that he gave us such a great offer.

When I look at the finished book, I see that the people in the photos all have really nice smiles on their faces, which is not necessarily a sign of good photography, but rather commemorative photos that capture the moments they bought their favorite book through conversation. Each of facial expressions captured in the photos shows how much they love Dashwood Books, and I think we have created a wonderful book in which you can get a real sense of how rich our place and community are from every single photograph.

–What do you want to do with Dashwood Books in the future?

Susuda: Exactly as we have done so far, we would like to continue to grow as a creative community where we can exchange ideas with our customers, and at the same time, we hope to keep on publishing wonderful books so that our list of publications will be as valuable as the place we are in.

Dashwood Books plans to open a gallery in the East Village aside from the current space. It will not be a gallery in the traditional sense, but more like a unique place that will deal with installations and experimental works. I think one of the best things about Dashwood Books is that it actively takes in new works by talented artists who are going to break through, so I want to be able to nurture those artists.

(※1) Some Of Miwa’s Favorite Dashwood Friends Of The Day, a photobook, was published by Nick Sethi’s publishing house DAK0TA and the book signing event was held at this year’s “New York Art Book Fair” organized by Printed Matter.

https://www.dashwoodbooks.com/pages/books/24058/nick-sethi-miwa-susuda/some-of-miwa-s-favorite-dashwood-friends-of-the-day

Direction Akio Kunisawa

Photography Ayako Moriyama