Hajime Sorayama

Born in Ehime, Japan in 1947 and currently based in Tokyo. In 1999, he designed the concept for Sony’s entertainment robot AIBO, and in 2001, he designed the album cover for the international rock band Aerosmith’s Just Push Play (2001). In recent years, Sorayama’s collaboration with Kim Jones for “Dior Men” has been the talk of the town. Sorayama’s recent works include “Unorthodox” (The Jewish Museum, New York, 2015), “Desire” (by Larry Gagosian and Jeffrey Deitch, Moore building, Miami, 2016), “The Universe and Art” (Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2016; Art Science Museum, Singapore, 2017), “Cool Japan” (Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, 2018), “Tokyo Pop Underground” ( (Jeffery Deitch, NY/LA, 2019-2020), “Sorayama x Giger” (UCCA Labo, Beijing 2022-2023), and a major solo exhibition at the new Museum of Sex In the summer of 2023, a large-scale solo exhibition at the new Museum of Sex in Miami, Florida, USA, is also in the works.

http://sorayama.jp/ja/

https://nanzuka.com/ja/artists/hajime_sorayama

Instagram:@hajimesorayamaofficial

Painter/illustrator Hajime Sorayama is currently showing his new exhibition, Space Traveler, at three venues in Tokyo. Standing in front of his installation of a robot sculpture at NANZUKA UNDERGROUND, the main venue, the artist says, “When you stare at it for too long, you start to get dizzy. It’s like space motion sickness,” with a cheeky smile across his face.

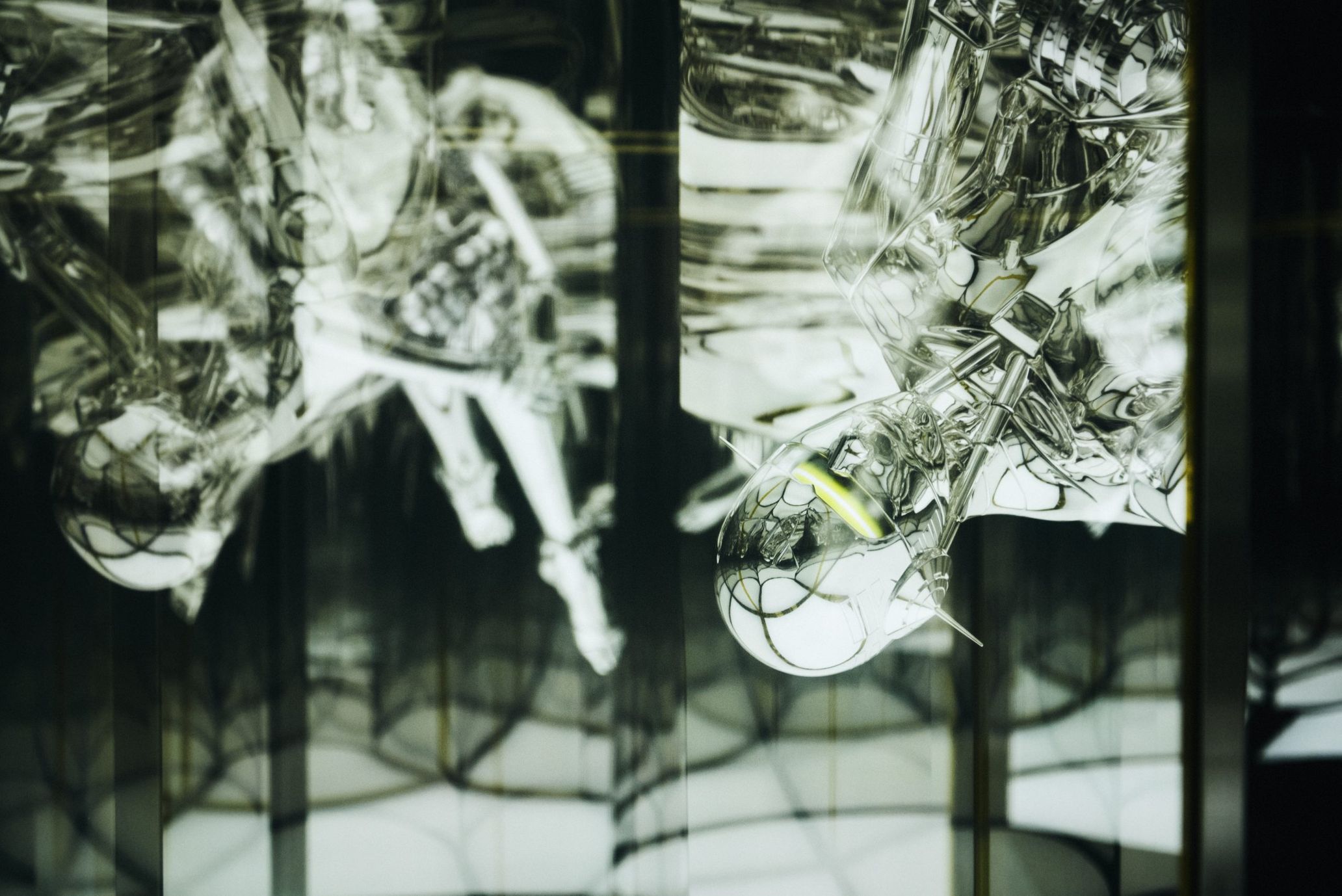

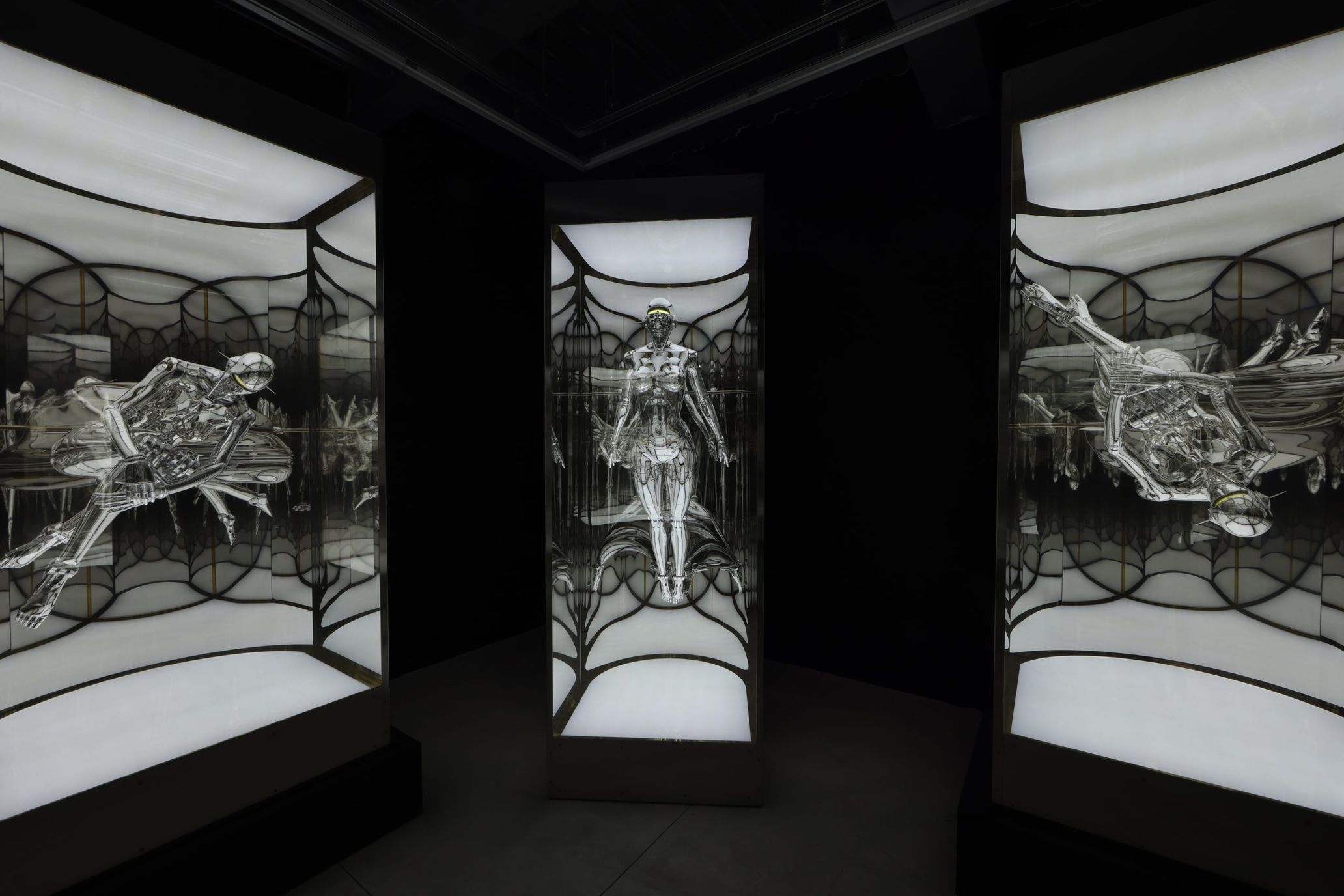

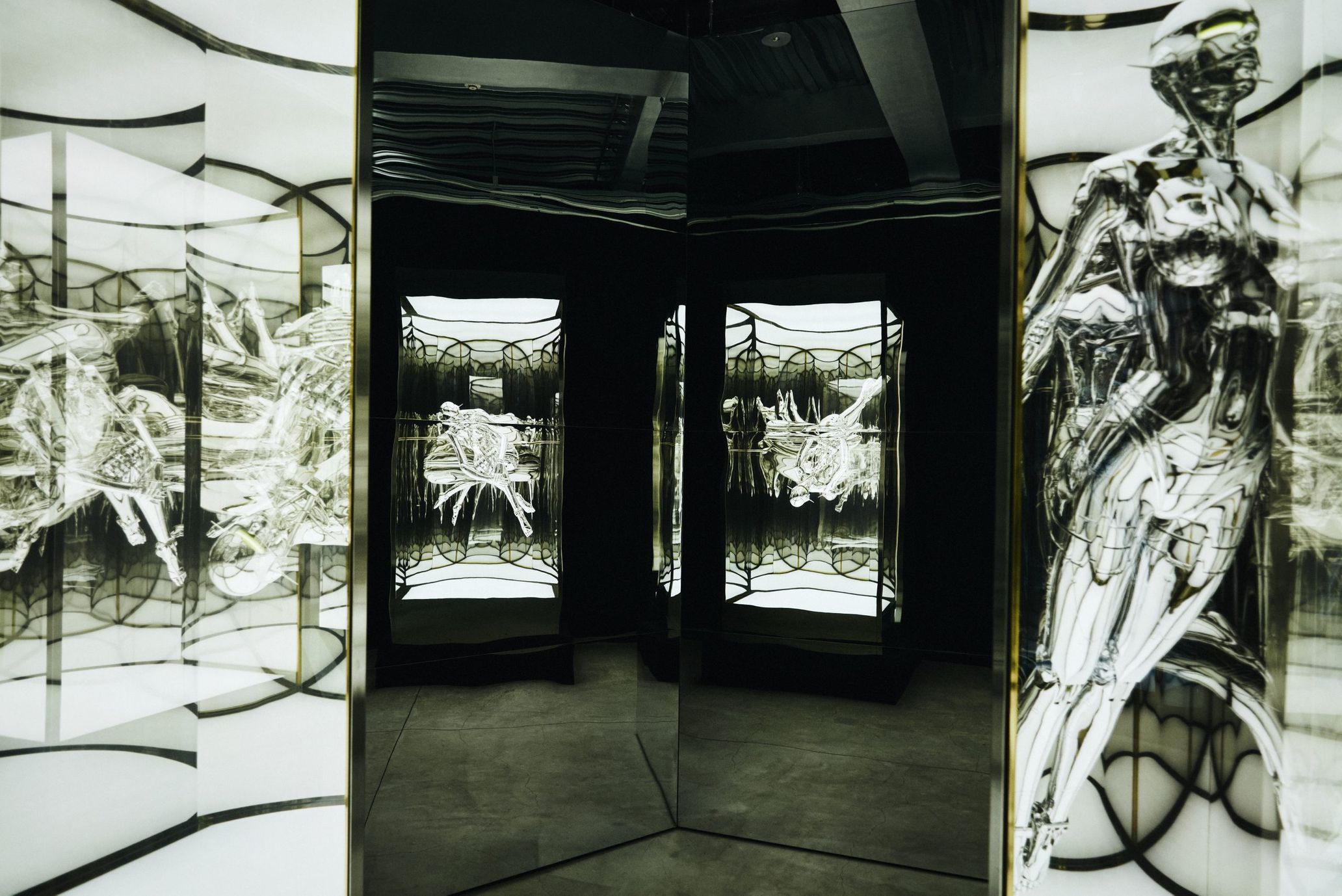

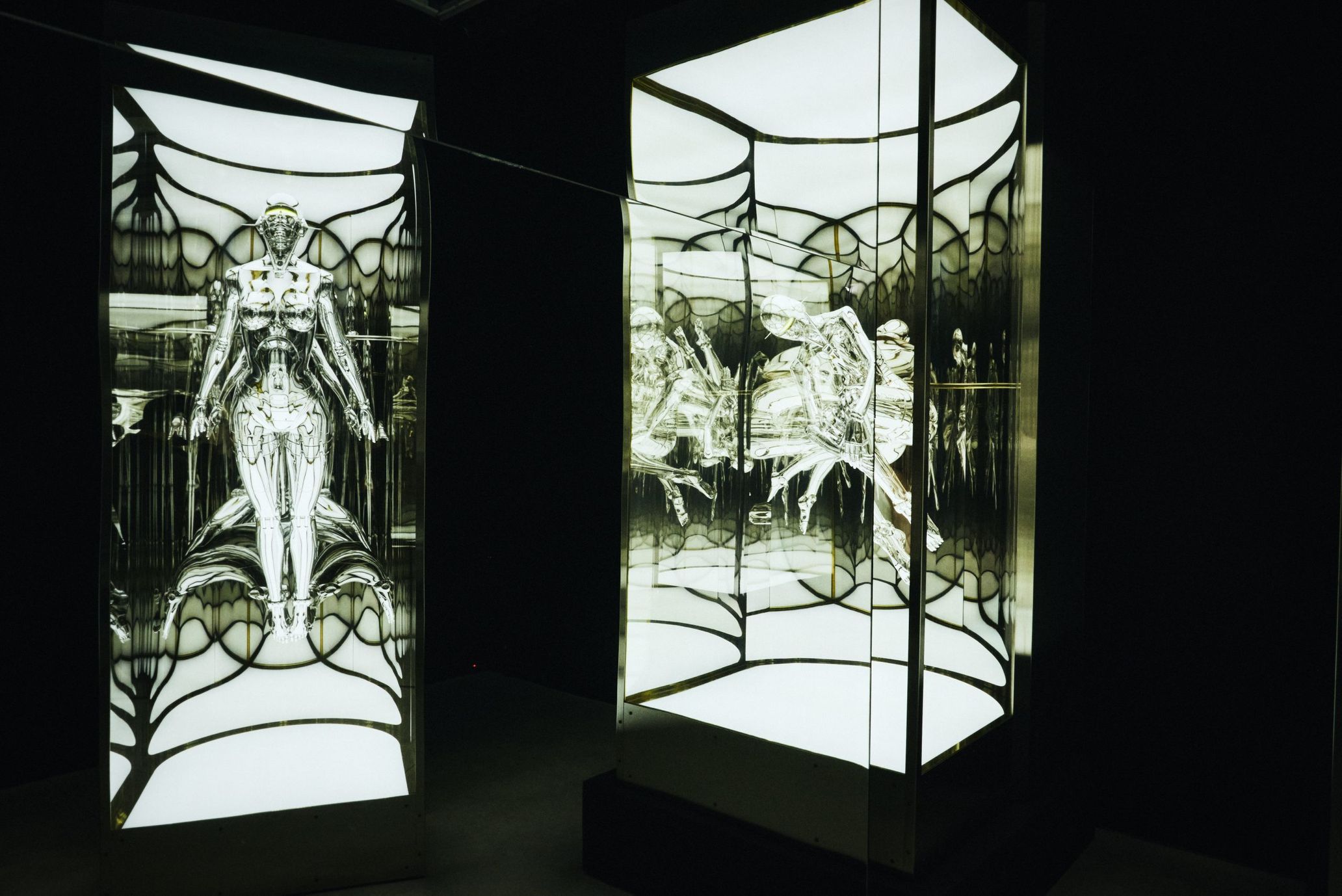

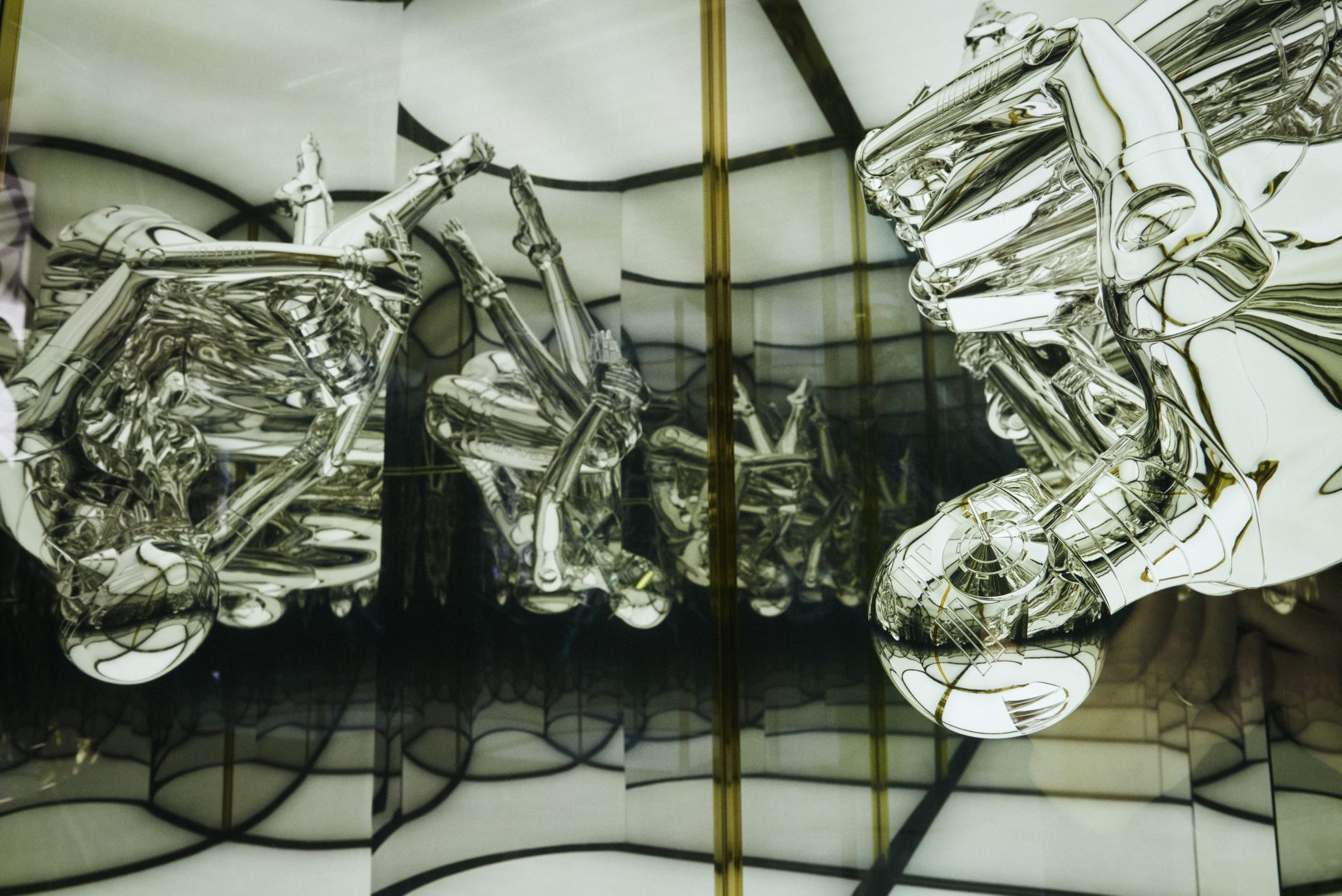

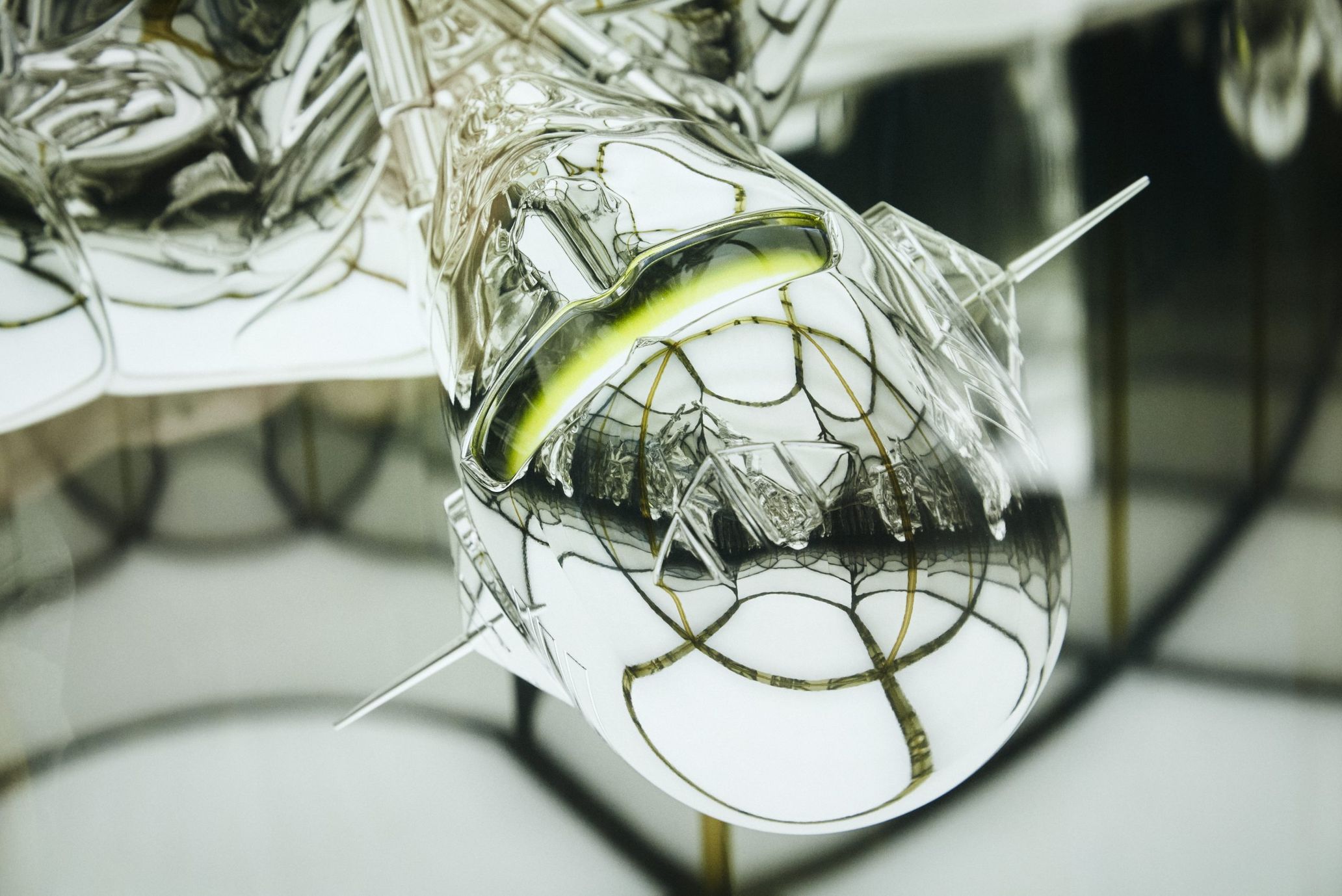

The installation, which uses up the entire first floor, has six female robot sculptures placed in individual containers with mirrors inside, making the robots appear as though they’re floating. An infinite number of robots can be seen in each mirror, and due to the difference and distortion between the actual sculptures and their reflections, the viewer starts to feel something akin to “space motion sickness,” as described by Sorayama. “You might get sick if you look around while moving. You have to be very careful. It’d be a mess if you threw up inside the gallery, right? (laughs).”

Sorayama is known across the globe for using what’s come to be known as “sexy robots” as central themes in his work, which could also be described as “robot shunga.” The artist shocks the public whenever he creates something new, including collaborations with domestic and international musicians, artists, and corporations. It seems as though Sorayama’s latest exhibition is full of surprises that speak to the senses. “I feel like that’s the point. I make art to surprise people.” He grins again. Below, Sorayama shares exclusive details about his new exhibition and creative philosophy with us.

Developing art one step at a time

—For your installation of human-sized robot sculptures, you used mirrors to show your work in a new way.

Hajime Sorayama: You don’t know how such effects would turn out unless you test them rather than simulate them. I showed one of the sculptures that use mirrors at Art Basel in Hong Kong (one of Asia’s biggest art fairs) this year, but this is the first time I’m showing several within an exhibition space I worked on in Japan. I develop my artwork step-by-step, thinking, “What would be interesting to do next?” Creating egg-shaped containers, not rectangle ones, would have been ideal, but it was technically and financially implausible. I want both the floor and ceiling to be curved next time.

—The sculptures—the motif of the exhibition—look like they’re floating. The name, Space Traveler, matches the exhibition too.

Sorayama: The gallery came up with the name. The only thing I wanted to do was to make the sculptures float. I made the sculptures with a craftsman at a workshop, and they gave it their all when I made unrealistic requests. They said, “Well, let’s make it happen, then!” Some robots are in the air with their knees drawn to their chests, while others are on their tip toes in a pose similar to a swimmer about to jump off a diving board. I asked them to make the robots’ bodies lean forward without the support columns showing, which was hard because the sculptures were heavy and made from aluminum.

—How did you decide on the robots’ poses?

Sorayama: The ones hugging their knees resemble the first-ever female robot I drew. The other pose, the moment someone’s about to jump off a diving board, actually comes from an illustration of a robot I drew with the words “freedom” and “liberation” in mind. In the image, the term “hikari” (meaning “light” in Japanese, a nod to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s last words, “More light!”) and the human rights organization Amnesty International’s candle logo look like they’re floating in the background. I rearrange old works and retouch old paintings quite often.

—The reflections [of the robots] are interesting too. For instance, in the back, you could see patterns reminiscent of art deco (a decorative style characterized by straight lines and geometrical shapes that represent the advancing industrial civilization in the first half of the 19th century). You previously said your metallic female robots are like goddesses. In this exhibition, I noticed a circular shape behind the robot sculptures. It made me think of something zen-like, where I could meditate on my own Buddhist nature.

Sorayama: You can interpret my work however you want. You can let your thoughts run wild or put your hands together and bow. I always test how my installation would affect someone walking into it every time I have an exhibition. It’d be boring to show something that’s just printed out because what I want to do is to stun people. The best part of my art is surprising people.

I tried doing something on the second floor of NANZUKA UNDERGROUND. First, when you enter the room, your eyes go to a painting of a motif based on the skeleton of a Futabasaurus. I made it a bit flat, as though it were stretched out. It looks slightly panoramic. The canvas for this is divided into three panels, and I placed the panel with the neck and face at a certain angle utilizing one of the corners of the space. When you approach the painting, it feels like the dinosaur is looking at you. Usually, corners like this are considered useless, and many people place three-dimensional pieces there, but I always felt like those corners were valuable enough to use. I often wonder if paintings could be shown on curved surfaces.

Bigger artworks are more persuasive and unexpected

—The exhibition also includes paintings made on large canvases. You’ve recently been enthusiastically making large paintings, but what was the catalyst?

Sorayama: My answer is simple; bigger pieces are more persuasive and excite people. To mention one catalyst, I saw The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David (the second largest painting at the Louvre), about nine meters wide, at the Louvre in Paris around 30 years ago. David’s signature on the corner was as big as the biggest painting I made. I thought, “I’m going to paint a bigger painting than David’s.” But alas, I couldn’t paint something as big as that in Japan, partially due to the circumstances of housing here. I couldn’t take on the challenge for a long time, but I started renting a spacious studio a little while ago. So now I’m redeeming myself after 30 years.

—I heard you incorporate a traditional technique used for oil painting called sfumato, where you blend transparent layers on top of the paint. It seems like you enjoy trying out different old techniques.

Sorayama: In my case, I use acrylic paint, not oil paint. Oil paints smell bad and dry quickly, so they don’t suit my painting style. I don’t, however, copy old painting styles; I mix different techniques. For example, I sometimes use prints as a base. Specifically, I would recreate a hand-drawn illustration in 40 megapixels and print that out onto a giant canvas using 12 colors. I would then add various colors of paint, such as fluorescent colors. Art collectors give me a weird reaction when I tell them I utilize prints, but I use giclee printing, which uses dyes; that way, I can get a very clear shade of blue that I can’t with oil or acrylic paints. It’s close to a radiant color you’d see on a monitor screen—kind of like light. There’s no reason for me not to incorporate such techniques, right?

—You’re showing a video using CG technology for the first time.

Sorayama: To be honest, I’m still not at all satisfied with the video. The body in it isn’t shining at all. There were issues with the budget and time constraints. It’ll take 100 years to complete it. The last scene has a motif of the earth with a diamond ring, and I asked them to put a slight time lag so that its reflection would show on the robot. I thought you could do anything with CG, but that’s not true.

—You can freely draw things that would be financially difficult to make with CG. In other words, you do something CG can’t do through painting.

Sorayama: With painting, you can do whatever you want if you take the time to work on it manually. Sure, time and money were concerns, but I noticed a difference in how artists and those who work in science and technology think. In some cases, you can’t easily create something visually organic and soft with a computer. People working in animation always talk about the uncanny valley, right? The term refers to a “valley” where something becomes disturbing the more realistic it becomes. It gets creepy once it crosses a boundary. I also think this has something to do with how the brain perceives reality.

The artist’s role is to express the opposite of the norm

—A lot of foreigners have been coming to your current exhibition. Is there a difference in how people respond to your art in and out of the country?

Sorayama: There isn’t much of a difference at the moment. I feel like my art has no borders. Even in Japan, the responses between Tokyo and other prefectures aren’t that different.

—Some of your works deal with sensitive subjects. Do you ever receive complaints?

Sorayama: Hmm. There’s no point in overthinking it. Whenever I make something, I never think about such things. I don’t really consider whether I’ll exhibit whatever I’m drawing/painting at the time. I only draw what I like, to begin with. I only think about social themes when I have an exhibition like this one. But I don’t have to be worried about complaints because the gallery takes care of them (laughs). It’s not good to demand artists to make socially acceptable works too much. You can say artists are the antithesis of the norm, in a way. After an artist puts their work out, all they have to do in the end is to say, “Oh well, I don’t know.”

People tend to appreciate erotic illustrations and pornography less than fine art, but they’re the same to me. Like food and sleep, sex is a fundamental human desire you can’t neglect. The robots I drew were initially pornographic and derived from pin-up girls.

—It’s like an ideological attack, in a way. I believe one of the reasons young people are drawn to your art is not only the art itself but your attitude.

Sorayama: Takeshi Kitano came out with a new film called Kubi recently. Things during Nobunaga Oda’s time were even worse than today, with all the deceiving and killing that went on. Takeshi-san is brilliant because he didn’t create a clean-cut heroic story like one of those mainstream period dramas. This isn’t limited to artists; take Jacques-Yves Cousteau, a French oceanographer who invented a regulator, a diving apparatus, called the aqua-lung. He lost his son while developing the device, but that didn’t stop him. In my eyes, those who continue doing what they want to do regardless of taboos and criticism are brilliant.

—I think it’s true to your character to describe such people as brilliant. Regarding your female robots, which all have a metallic shine, you said that you see god in light and that your god is a goddess, that the light is a girl.

Sorayama: I don’t remember what I said that long ago (laughs). There’s a limit to the fake or artificial light you can imitate. To be blunt, impressionists can’t paint a light that’s more intense than the sun, right? Today, you can make something look like it’s shining through CG technology, and the viewer can also tell when something is supposed to represent light. But the question is, how much can one surprise others that way? I want to create a light that’s almost unbearably bright through drawing. I know I can’t produce a light brighter than the scope of the shades between white and black because it’s a drawing. It might be a losing battle, much like Don Quixote charging toward a windmill, but I want to create a light that would make people surprised and ecstatic. I’m constantly pushing those boundaries.

Translation Lena Grace Suda

Photography Hironori Sakunaga

Hajime Sorayama

Space Traveler

April 27 (Thu.) – May 28 (Sun.), 2023

NANZUKA UNDERGROUND

Open: Wednesday – Sunday / 11:00-19:00 *Closed on Mondays and Tuesdays

27th (Thur.), 2023 – TBD

NANZUKA 2G

*Opening hours are same as Shibuya PARCO

April 26 (Wed.) – May 27 (Sat.), 2023

3110NZ by LDH kitchen

Wednesday – Thursday / 11:00-16:00 Friday – Saturday / 11:00-17:00 *Closed on Sundays, Mondays, Tuesdays, and Holidays

https://nanzuka.com/en/exhibitions/hajime-sorayama-space-traveler/press-release