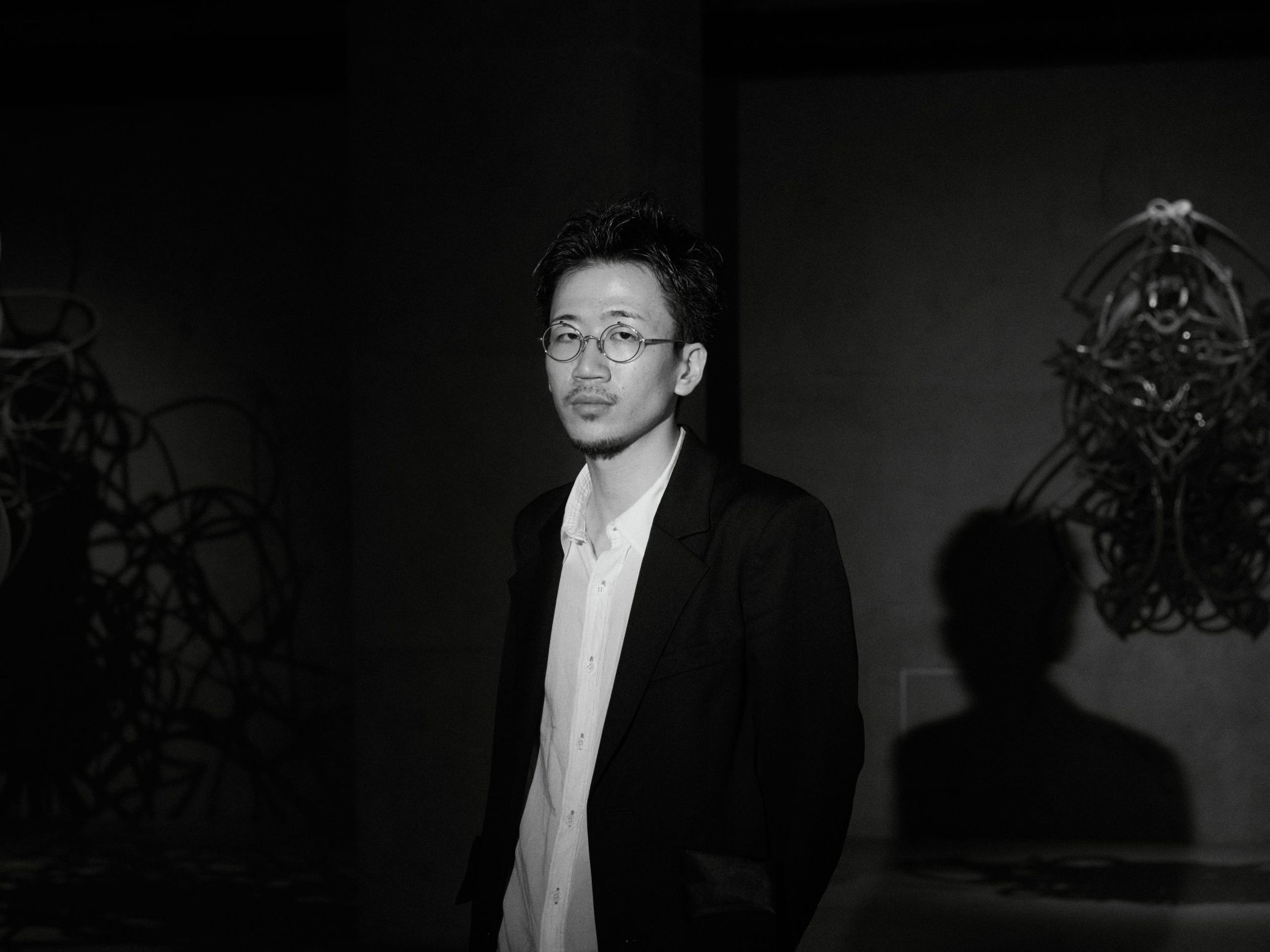

Ryunosuke Okazaki

Ryunosuke Okazaki is a designer of his own label RYUNOSUKE OKAZAKI born in Hiroshima in 1995. Okazaki finished the Graduate School of Design, Tokyo University of the Arts, in 2021 and held his first runway show, “000,” in September 2021. He was selected as a finalist for “LVMH Prize 2022” in 2022. He is currently based in Tokyo.

https://ryunosukeokazaki.com

Instagram:@ryunosuke.okazaki

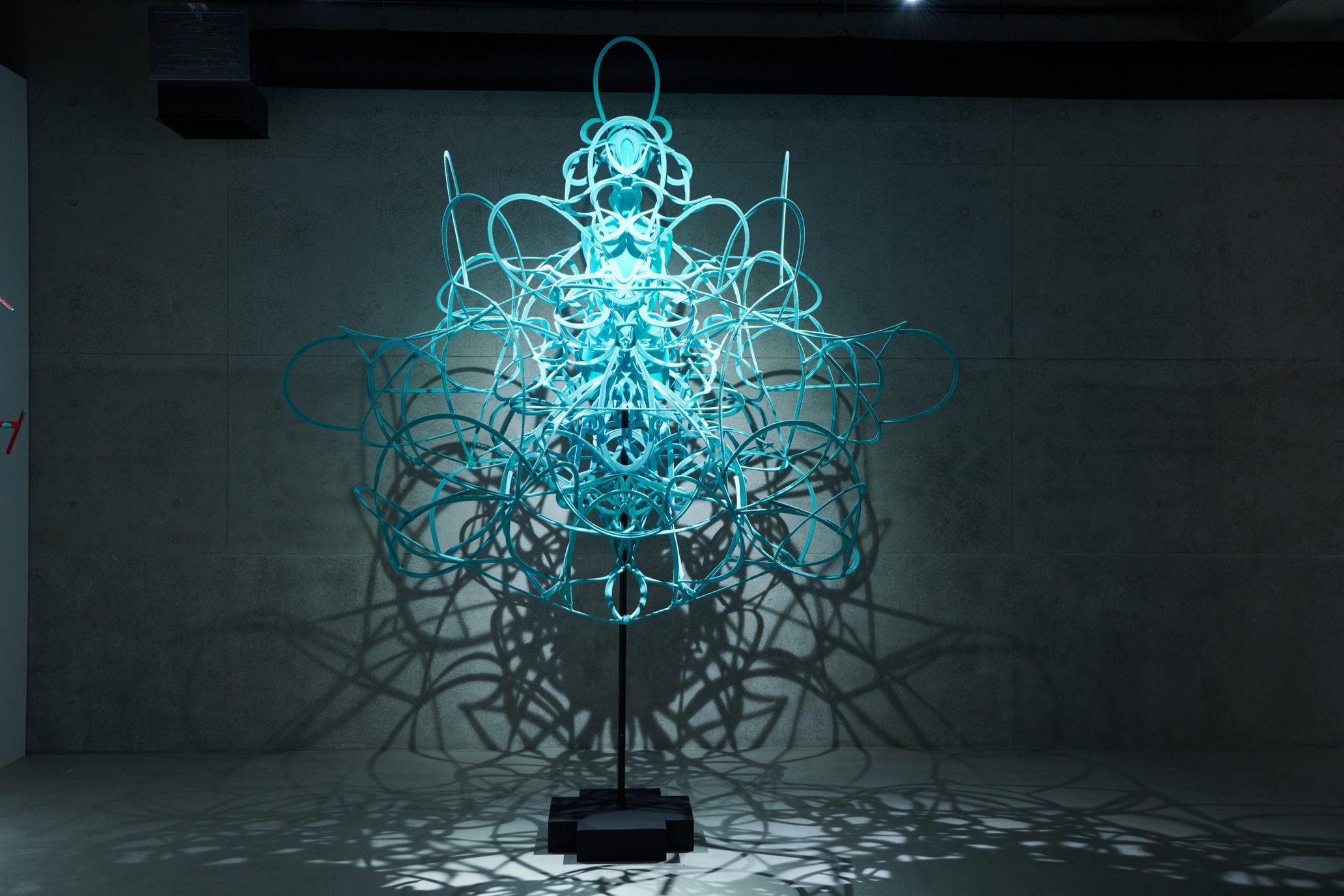

Okazaki’s debut show, “000” which showcased the organic beauty of formative art created out of everyday materials, made a significant impact, and his second runway show, “001” marking the label’s second season, vividly made its unique dress style widely known. Immediately after that, he was selected as a finalist for the “LVMH Prize 2022,” which led the designer of “RYUNOSUKEOKAZAKI” to accomplish the remarkable feat of getting an opportunity to present his work in Paris less than a year after his debut. The latest presentation, “002”, his first in about a year, was delivered not in the form of a runway show but a solo exhibition held at the creative space “THE FACE DAIKANYAMA” in Daikanyama. We sat down with him and asked about his thoughts on his new collection in this art gallery-like space with its walls lined with wood sculptures.

–The exhibition’s atmosphere is very different from a fashion show and is more like an art exhibition. Is this the first time for you to exhibit your works on the wall?

Ryunosuke Okazaki (hereafter, Okazaki): Yes, it is. Up until now, I have presented three-dimensional works worn by models, so this is the first time I have exhibited my work in a static form like this. You can hang the pieces with red cloth hanging from the ceiling on the wall. I would be happy if the fans of “Ryunosuke Okazaki” could see a new aspect of my work. Also, this is the first time I used wood.

–I was surprised to see how even a wall-hanging work becomes three-dimensional when you create it.

OKAZAKI: If I had to choose between three-dimensional and two-dimensional, I would go for three-dimensional like this. I layer the parts from various angles and attach them side by side. Then, I make them while imagining symmetrical forms.

–How do you express the idea of symmetry?

OKAZAKI: My oldest source of inspiration for symmetrical forms is the torii gates for the Shinto shrine. I grew up in Miyajimaguchi, Hiroshima, where Itsukushima Shrine was located close. As an elementary school child, I fished and played every day, and I could always see the Torii gate just across the shore. Also, one of my most influential experiences was making a bright red Torii gate out of piles of cardboard when I was in kindergarten. I found torii gate really cool, and even as a child, I had a vague but special feeling about it.

–Historically speaking, some in the architectural world have considered asymmetry to be humanistic.

OKAZAKI: Certainly, if you look at architectural styles in both Japan and the West, there are a lot of asymmetrical structures. On the other hand, there is a sense of order and will in symmetric things, and I sense life in them. This sensation is instinctive. Technically, all living creatures, including humans and insects, are asymmetrical, but if you look at their overall forms, they tend to be symmetrical.

Working on artwork with wood

–The name of your new series of works using wood is “PIMT.” What does it mean?

OKAZAKI: I coined this word by combining the first letters of “Perception,” “Intention,” “Material,” and “Time.” The “time” of “perceiving” the material, sensing the “intention” behind the form, and creating with the “material” is connected to the act of “prayer” that I cherish within myself. So I call it “PIMTO,” and I also like its sound.

–The sound of the word “JOMONJOMON” (a series of dresses inspired by Jomon earthenware) is also impressive.

OKAZAKI: Thank you. Yeah, I put importance on sound because artworks are something to be loved.

–It’s interesting that even when the textile is replaced by wood, your work is easily recognizable as “RYUNOSUKE OKAZAKI.” Is the production process the same?

OKAZAKI: It’s precisely the same. I’m working on various materials as if breathing life into my works. Each piece has its own personality, and I feel as if it is alive.

–I heard that you don’t make drawings. Is it right?

OKAZAKI: I create forms fortuitously by moving my hands. It’s probably the same as how I paint. A painting never ends, does it? My dresses never end as well. How the creation process ends changes according to the level of experience. Experiences introduced to my hands affect how they move, which is reflected in my work. Interestingly, my work is completed when people wear it.

–What made you decide to work with wood in the first place?

Okazaki: It all started when I visited Nikko Toshogu Shrine last April. The wooden structure I saw there struck me immensely. Kigumi is a traditional Japanese construction method used by temple carpenters to build shrines and temples. In my case, I did not use the original form of kigumi, but I was inspired by the process of assembling the wood, how the structure looked when they were put together, and how colorful they were.

–As you mentioned, you’ve got a lot of colorful pieces. The moment I saw them, I thought they looked like Gundam.

OKAZAKI: I get that response a lot. Actually, I have never seen any Gundam anime, but I suppose there’s some connection. I think Japanese culture is good at designing and inventing imaginary creatures, which I think has something to do with our long history of finding the existence of gods in nature. I personally feel that robot animation is also connected to the Japanese culture of prayer, so perhaps it is inevitable that my works look like Gundam.

–And you have created a lot.

OKAZAKI: Actually, there are many more works behind this exhibition venue that I haven’t exhibited yet. I have been working on them since the end of the LVMH Prize exhibition I participated in last year.

–So you’ve been working with wood for almost a year?

Okazaki: Along with the wooden pieces, I also created dress works. The time I spent working with the fabric and the time I spent working with the wood were well-balanced, and the dresses became more sculptural and delicate. This time, since no models would wear them, I could create works that are even taller than I am, with more freedom. Creating a space that allows viewers to face the pieces is an important mode of expression for me.

–Are you working in your studio?

OKAZAKI: Yes. Ensuring adequate space is such a challenge because many of the works are huge. Among all, I am probably the one who is most pleased to be able to stand in front of my own artworks and face them in this way. I hope many people will see them.

I will keep following my path without distinguishing between fashion and art.

–Your works have been all unique pieces, right? And will they always be?

OKAZAKI: Yes. I’m sure they will continue to be so because I want to communicate with my works, and I also want to connect with the people who see them. So I will keep on creating my pieces, focusing on demonstrating what I feel at the time.

–You have been fascinated with the fashion world since you were a middle school student. So what kind of fashion style were you, a person born in 1995, looking at?

OKAZAKI: I don’t remember a specific fashion label, but I watched many collection videos and fashion magazines and liked to wear the clothes myself. I was attracted to the appearance of fashion style rather than the context of mode. What I was struck by, within collection footage, was something like people didn’t look like people at all, people who seem to be liberated and become wilder, and people in artificial forms.

–You were interested in the act of dressing itself?

OKAZAKI: Yeah, I was. The art-piece-like outfits you see in fashion shows, in particular, express the essential part of dressing, which links to the question of what kind of things human beings living on the earth wear. People are part of nature, and the Japanese, in particular, are creatures who have been conscious of this. My interest in fashion, especially as a student, was based on my childhood experience, such as catching insects, fishing, and drawing pictures in nature. The fact that I was born in Hiroshima and that my theme is “prayer” is also all connected.

–You have become known worldwide since the debut with “000”. What kind of people have approached you?

Okazaki: Those of the fashion industry. And their interest opened up my possibility. The experience of being selected as a finalist for the LVMH Prize and presenting my work in Paris meant a lot to me. I want to show my work in Paris again, and I would also like to present my art pieces in New York. The fashion and art markets are different, so a line is drawn between them, but I wouldn’t make any distinction between them. Creators should be freer and should pursue what they like. I have many goals, so I want to focus on intensifying the power of my work, creating and communicating in various places.

–Is there anything you are planning for this year?

OKAZAKI: I will continue to create as always. The works I will present in this process will surely connect me with the world.

–So will this sequential-numbered series go like 003, 004, and so on?

OKAZAKI: Yeah. I want to work on this at least until 100 throughout my life. At the time when I started with “000,” which became a turning point for me, I was already determined to do it up to three digits. Precisely because these simple sequential numbers are given to my works as titles, they express even more vividly the fact that I will be creating history through my life and continuous artistic practice.

Translation Shinichiro Sato

Photography Tameki Oshiro