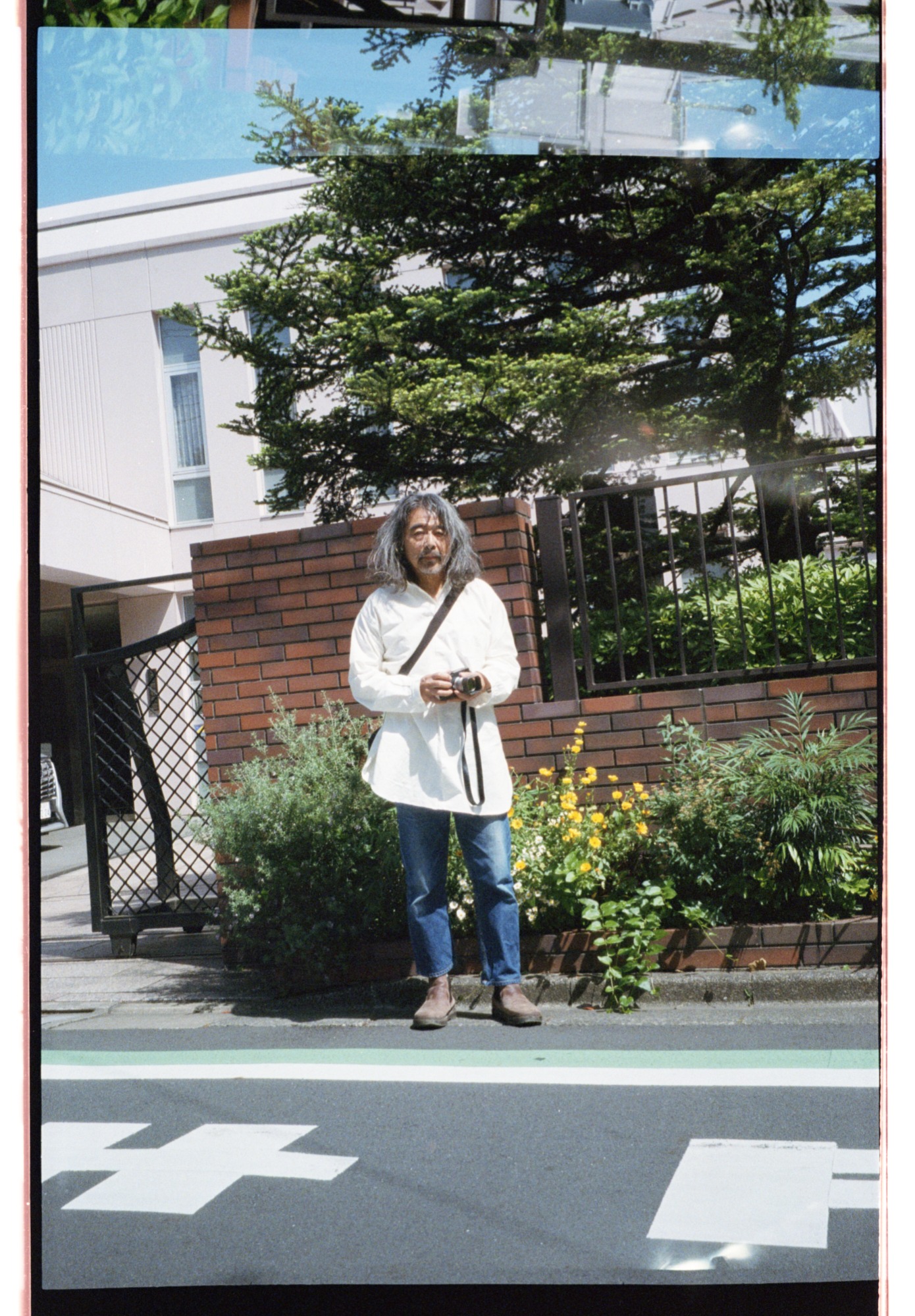

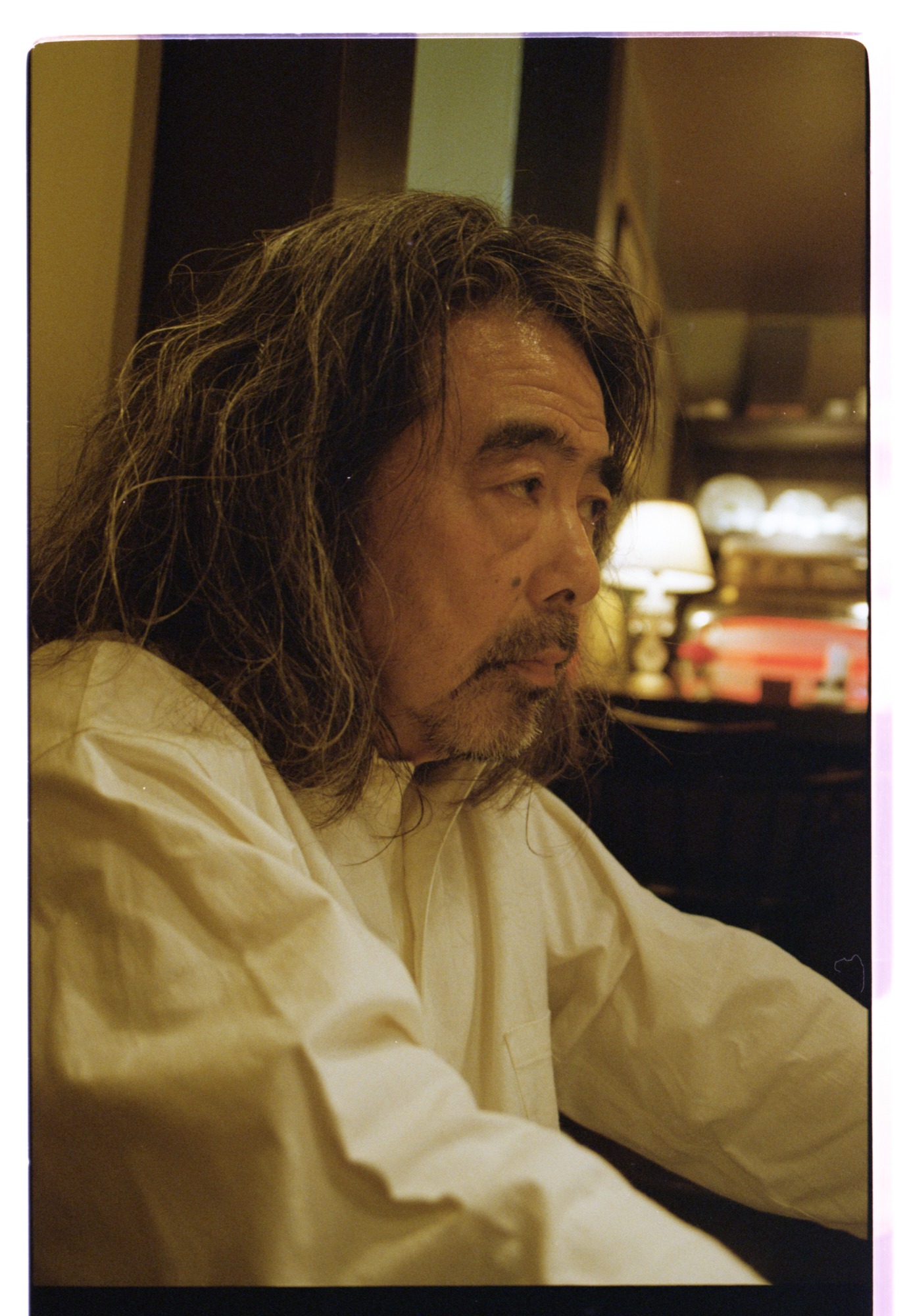

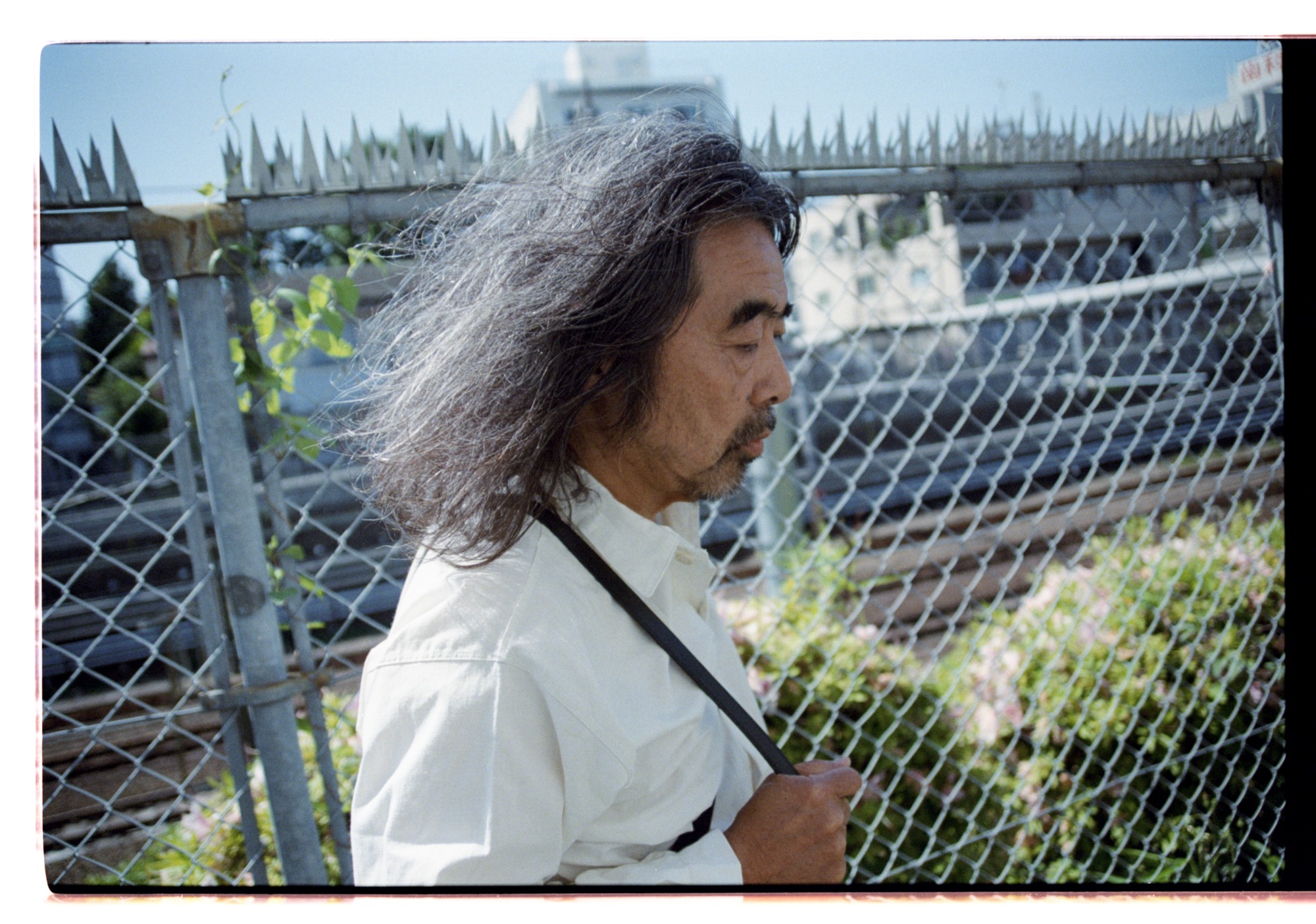

Kyoji Takahashi

Born in 1960 in Mashiko Town, Tochigi prefecture. In the 1990s, his work was published in fashion culture magazines such as Purple as well as in advertisements. His main photo books include: The Mad Broom of Life (1994), Road Movie (1995), Takahashi Kyoji (1996), World’s End (2019), Ghost (2022), Void (2023), among others. His solo exhibition Void was held in Kyoto in May.

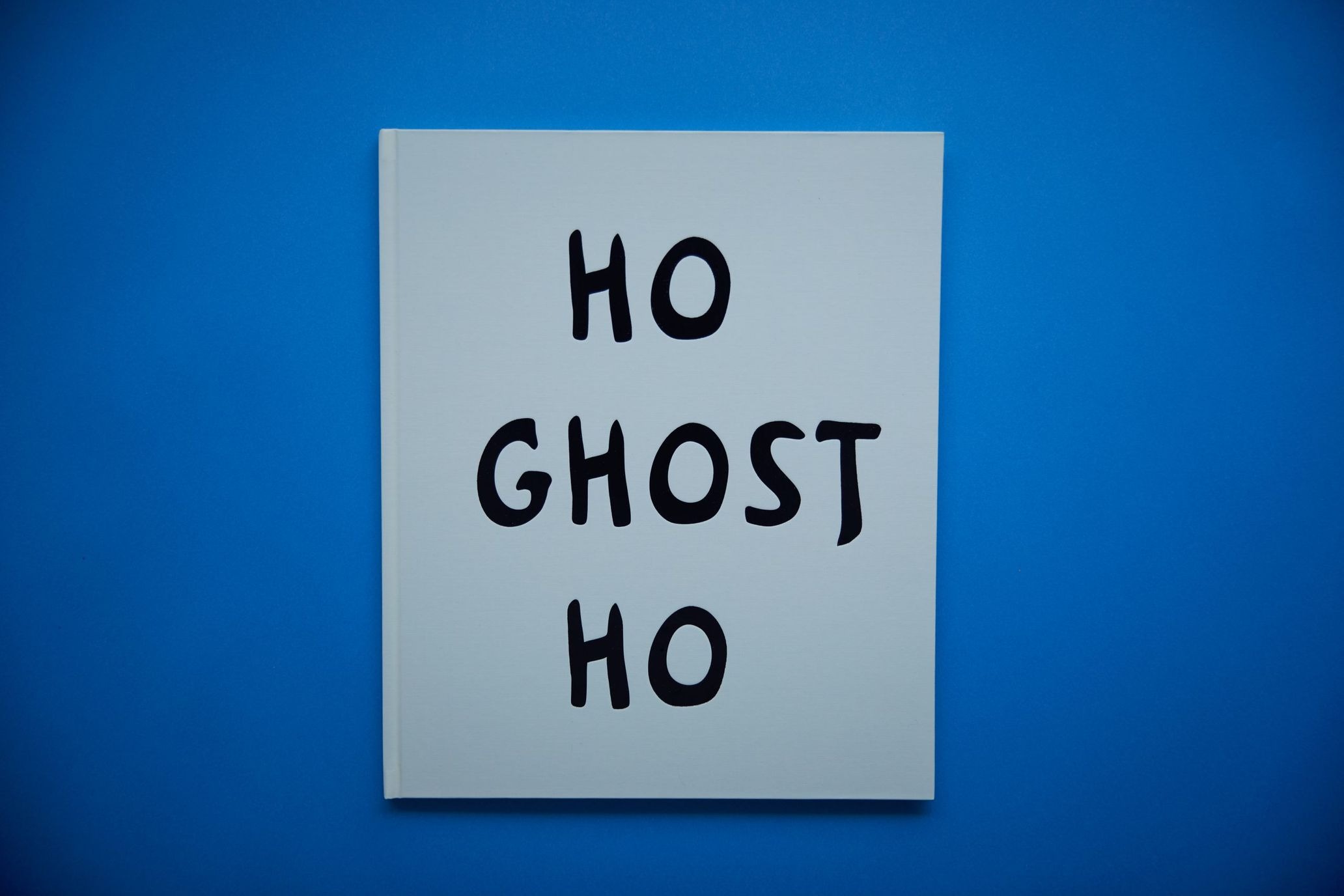

Photographer Kyoji Takahashi’s latest exhibition, titled “Void,” is currently taking place at Artro in Kyoto. Through this exhibition, Takahashi employs his beloved everyday camera, the Leica M8, to convey his personal perspective, capturing the scenes visible from the tranquility of his own room. In conjunction with the exhibition, a photo book has been published, combining evocative texts with the photographs that were shared on Instagram. How does Takahashi establish a connection between his images and the accompanying words? We delve into the journey of Takahashi, who has dedicated himself to the art of photography with unwavering consistency.

“It’s important to reserve time to not look at photos or listen to records”

– You posted on your Instagram that the theme for your current exhibition “Void” might be “darkness” or the “yin” in yin-yang. How did you land on this theme? Could you please clarify what you mean by the words ‘don’t cross’ and ‘darkness’ are also written at the end of your photo book as the text for the photo of traffic lights? It seems like you’re referring to the presence of these words in the photo book.

Kyoji Takahashi: I am not inherently inclined toward dark themes, and my photographs have never been particularly characterized by darkness either. However, considering the emergence of the COVID pandemic and the military invasion of Ukraine, we found ourselves in a period marked by a proliferation of distressing news. While I was aware of social media’s tendency to conceal negativity, there were moments when I experienced a sense of darkness within myself amidst it all. As a creative individual, it is not feasible for me to express only one polarized emotion, so I deliberately decided to delve into the deep recesses of that darkness.

– Why did you post all your work on Instagram?

Takahashi: Posting on Instagram felt like taking a shot in the dark because you never know who might be viewing it. I decided to experiment by sharing photos that conveyed a sense of negativity, just to gauge how users would perceive them. Surprisingly, I received messages from gallerists and staff members expressing their appreciation for a particular photo or expressing interest in exhibiting my work. This happened at a time when I had confirmed exhibition dates and the gallery venue, but the actual content of the exhibition was still undecided. It was a busy period for me, and I even fell a bit ill. The circumstances also left me with a sense of emptiness.

– The exhibition and the photo book share the title Void.

Takahashi: In my exhibition Ghost last year at LOKO GALLERY, I didn’t showcase a large number of pieces. Instead, I incorporated retrospective content and photos that I had collected since the start of my career. Alongside that, I had additional exhibitions to prepare for, which added to my fatigue during that period. Even my friends advised me to take a break, but I hadn’t fully recognized the toll it was taking on me. I was determined to persevere and push through it.

– The theme of “Void” revolved around capturing your personal perspective through photography, and the exhibition venue Artro had a room-like ambiance. In terms of composition, how did you approach it?

Takahashi: The venue layout was handled by the producer, Ken Kobayashi. Since we had a tight schedule for the flier, we entrusted the art direction to Christophe Brunnquell, who also worked on the photo book. The design for the flier was promptly delivered, but it featured a photo of Bukowski that wasn’t part of the exhibition. As for the photo book, my role was limited to determining the size and page numbers. Christophe took charge of the photo selection and layout.

What was amusing was that Christophe and Kobayashi had different selections, except for one photo. They viewed the pieces in separate locations and at different times. It may sound haphazard, but I believe that granting people the freedom to follow their own instincts can broaden possibilities. When attending an exhibition, you have the opportunity to physically observe the photos, but that is limited to the exhibition’s timeframe. Conversely, photo collections and books are akin to records in that they transcend time. Lately, I’ve come to appreciate the importance of setting aside time to refrain from looking at photos or listening to records.

– At last year’s “Ghost” exhibition, vintage prints from the early years of your career in the 1990s were displayed alongside your more recent flower photographs. There was a timeless quality to the exhibition; the images didn’t feel like mere records of a specific era or time.

Takahashi: The connection between time and emotions can impact our perception of linear time. For example, feeling anxious at night following an earthquake that occurred during the day exemplifies this. Time is not a constant entity. Books, being accessible for reading at any given moment, offer a different experience compared to viewing an actual exhibition. Unrestricted time can also affect the interpretation of specific pieces. For instance, in the case of “World’s End” released in 2019, Christophe initially suggested excluding text, but for “Void,” he later decided to include and design text.

– Is there anything specific that you considered or kept in mind when incorporating text into Void?

Takahashi: There wasn’t anything specific that I had in mind. The text included in “Void” is the same as what I posted on Instagram. We had the option to release the book with just the photos right before its completion, so the process of creating the book was quite flexible. Regarding the translation, we were unsure if we could meet the deadline after finalizing the printing process and bundling samples. However, since there were expected to be many overseas visitors for the KYOTOGRAPHIE program, it was important for the text to be readable. Photography researcher Kazuhiro Yasuda worked on the translation, and I’m grateful for his work because we ended up with double the number of translations compared to the number of works in the photo book.

A collage of image fragments weaves words

– I think the way your photographs complemented the text in “Void” was brilliant. It reminds me of Céline’s dismantling of literary style, an approach that goes against academic conventions. I’m curious about how these words and concepts come to you during your creative process.

Takahashi: I envision words in fragments and piece together a collage of these fragmented images, allowing me to establish connections between seemingly unrelated words. However, since social media tends to favor universal and positive emotions, it became important for me to incorporate negative and uncomfortable elements in order to break away from that pattern.

– Why did you shoot all the photos for “Void” on digital?

Takahashi: The reason is quite simple. Lately, I’ve been primarily using digital cameras for my photography. The recent projects I’ve been working on, such as the “Namacha” ad and the Fujin Kouron series, were all captured digitally. However, when it comes to Instagram, I typically share photos that I’ve shot on film and then developed. As for the photo book, Void, I decided to shoot digitally and share the printed versions on my Instagram account. The background used for the duplicated prints is actually my carpet. During the process of duplicating the prints, the hired photographer and I experimented with various techniques and ideas on the spot.

– The flower petals in the photo book looked like a painting.

Takahashi: The carpet serving as the backdrop for the photo likely gave the impression of a picture frame. When I sent the duplicated prints, I intentionally left them untrimmed, if the designer would handle the cropping process, given the large quantity of photos. Surprisingly, the prints came back in the exact sizes I had sent. Christophe has a knack for adding a touch of uniqueness to his designs, and everyone involved is consistently impressed by the remarkable quality of his work. We didn’t have any meetings or provide him with any specific instructions, yet his final output was flawless.

– These unexpected events make me wonder, do you think incorporating others’ opinions can lead to a broader range of possibilities?

Takahashi: It varies from person to person, but I believe that is generally true. Personally, I find photography intriguing because I enjoy the element of unpredictability beyond my control. Whether it’s magazines, advertisements, or photo books, they all share the commonality that the artist’s name is prominently displayed, yet the entire process, from printing to distribution, relies on teamwork.

■Void

Official Online Store: https://hadenbooks.stores.jp/items/6471cb11a89fa500326bfaad

Photography RiE Amano

Interview Yoshihiro Sakurai, Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)

Translation Mimiko Goldstein

Special Thanks to Kazuhiro Yasuda