Lovers’ rock, sweet and mellow music, was born in the U.K. in the 1970s as a subgenre of reggae. The compilation series RELAXIN’ WITH LOVERS was born in 2001 and contributed to the spread of this genre in Japan. The first album was the world’s first CD release of sound sources from DEB, a prestigious label founded by the late Dennis Brown and Castro Brown. The series continued to compile a selection of lovers’ rock tunes, from rarities to classics, while spanning different labels. By 2005, the series had released eight albums and played an important role in Japan’s acceptance and rediscovery of lovers’ rock (there are also five spin-off Japanese editions).

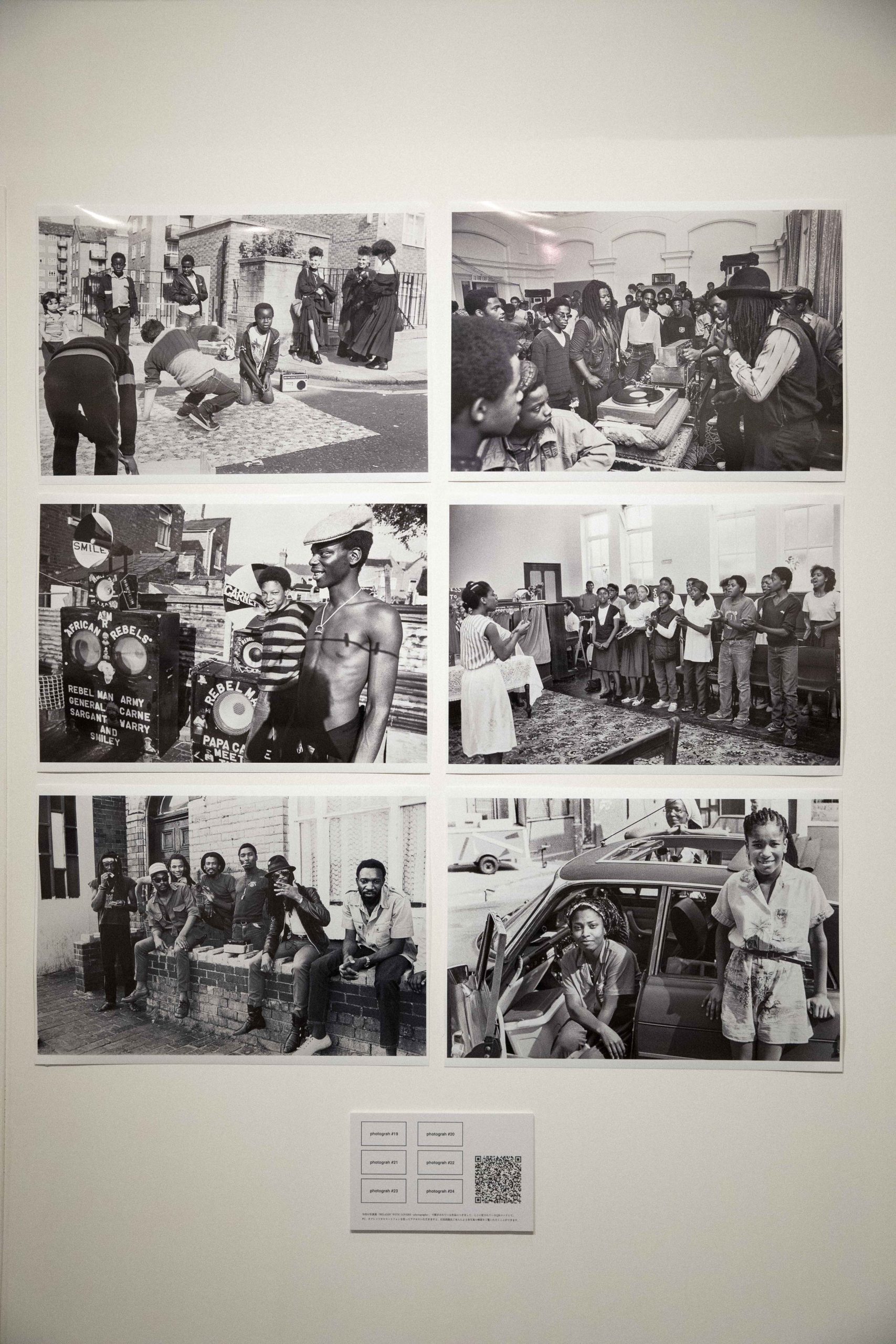

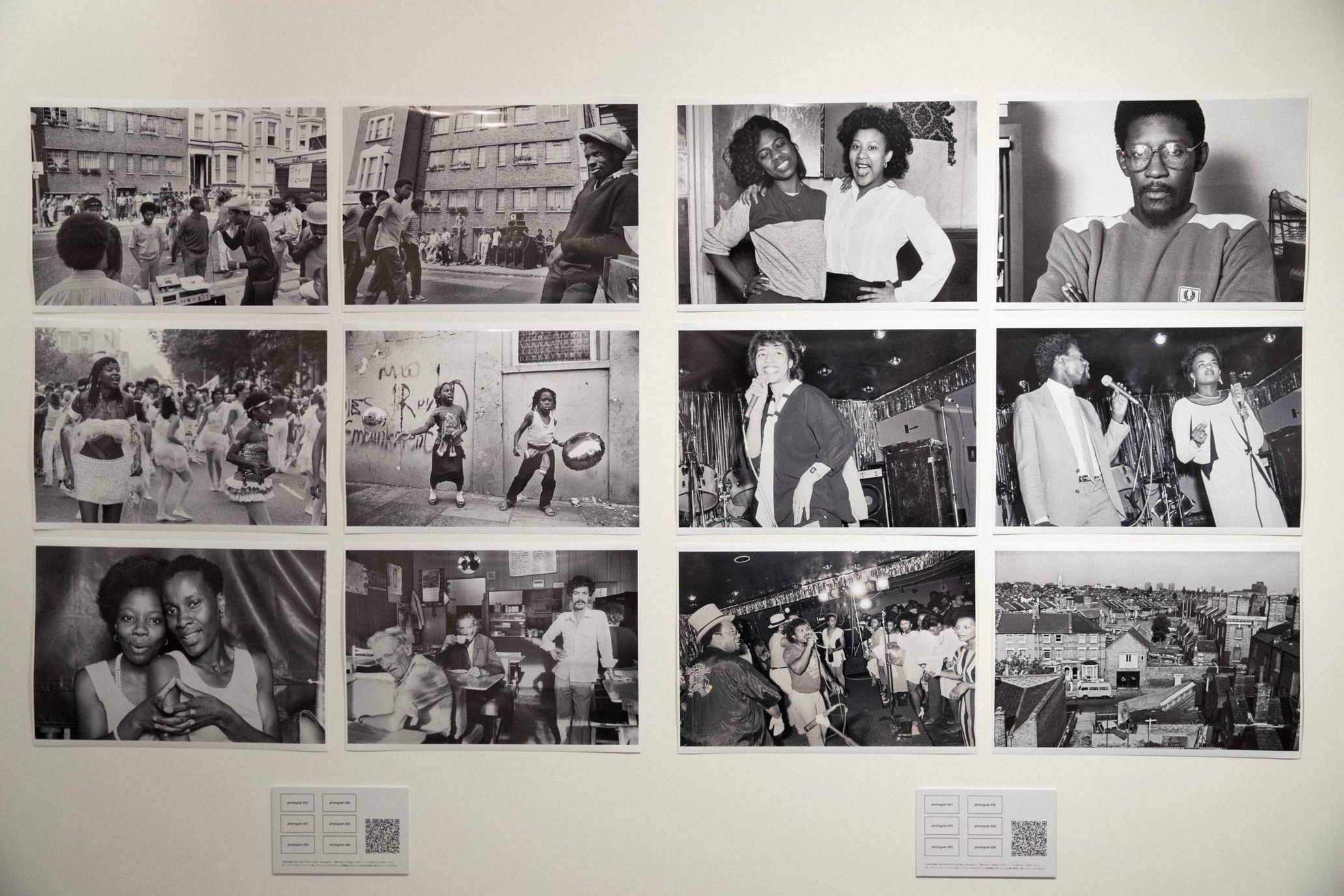

In addition to the exquisite selection of songs, what made the series so appealing was its covers. Those covers show the scenes and people photographer Masataka Ishida captured on film in 1984 when he traveled to Brixton, South London. Brixton, home to a large population of Jamaican immigrants, is a town where the culture and music of reggae were nurtured in the U.K. It is also an important location for the scene that has served as a stage for the movie Babylon (1980), which was screened for the first time in Japan last year after a lapse of more than 40 years.

In April, the gallery JULY TREE in Shinsen, hosted a photo exhibition, Masataka Ishida Photo Exhibition RELAXIN’ WITH LOVERS ~photographs~ comprising 36 photographs taken in Brixton and the other cities, including works used as covers of the series RELAXIN’ WITH LOVERS. What was Ishida thinking and feeling when he traveled to Brixton, and why was the romantic sound of lovers’ rock born amidst the harsh reality as exemplified by a series of riots in 1981? Music writer Ryohei Matsunaga, who visited the exhibition venue, asked Ishida about the memories and stories evoked by the photographs, which have yet to lose their luster.

Masataka Ishida is a photographer, whose writings/photobooks include 1989 If You Love Somebody Set Them Free (2019), Jamaica 1982 (2018), Soul Flower Union (2014), Alternative Music (2009), and Kuroi Groove (1999). His photographs have been featured in CD covers of a number of titles, such as Relaxin’ With Lovers, those of Janet Kay, Garnett Silk, Taraf de Haïdouks, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Jane Birkin, Faye Wong, Eikichi Yazawa, Soul Flower Union, Carnation, Yuji Hamaguchi, OKI DUB AINU BAND, and many others. He has traveled to more than 56 countries.

Twitter: @masataka_ishida

Instagram: @masataka_ishida

I went to Brixton to discover how reggae had changed since its arrival in the UK.

── Before coming here today for an interview, I read the comments written by you for each photo that can be read with QR codes at the venue. Underpinned by the sheer volume of information and your accurate memory, the comments themselves seemed like a thick book to read, and I thought it would be a wonderful experience to actually refer to them when viewing the photos.

With that in mind, I would like to hear about coincidences and inevitabilities associated with the encounter in the 21st century between the many photographs taken of real life in Brixton in 1984 and the sound of lovers’ rock, from your point of view.

Masataka Ishida (Ishida): Last year, the movie Babylon (1980, UK, directed by Franco Russo) was released in theaters in Japan for the first time, and the real image of reggae in London became known. Actually, that film was independently screened in Tokyo in the early 1980s, and I happened to be there to see the screening. Until then, the only images I knew of England were the ones I saw on TV, such as Buckingham Palace and London Bridge, so I was shocked. Of course, I had already heard British reggae music like Aswad and Linton (Kwesi Johnson), but for me, the film Babylon connected such music and the scenery behind them for the first time.

I went to Jamaica for the first time in 1982. Airfare was expensive until the early 1980s, so I could only travel abroad once every two years or so, but once got to Jamaica, the cost of staying was cheap. So once I went, I decided to stay there for three months. I went to England in 1984 as a next step of that trip. A part of me wanted to go back to Jamaica, but I also wanted to see how reggae music had transformed in the relationship between Jamaica and England. Looking back, England at that time was very much well-worth visiting. When I talked with Jamaicans in London, the fact that I had been to Jamaica opened a line of communication.

── At that time, there would have been very few opportunities to get a real feel for the local atmosphere.

Ishida: There were many people going to England from Japan. Whenever I went to a new wave show in London, there were always two or three dozen Japanese acquaintances who greeted me with words like, “Hello again.” However, there were no other people than me who paid attention to Black people in Brixton. There were people like photographer Ruiko Yoshida who were covering the civil rights movement in the U.S. in the 1960s, but not much attention was paid to the U.K. in Japan.

──You must have felt a lot of tension when actually having your base in Brixton and capturing the cityscapes and people on your camera?

Ishida: No, I didn’t feel much of that. Actually, it was quite easy to live in Brixton. There were many advertisements in the back pages of a free weekly magazine Time Out for something close to today’s Airbnb, and I could look for a place to stay. I always stayed at a place where I could stay for about 10,000 yen per week, including breakfast. Then, I checked the schedule of live shows in music magazines such as NME (New Musical Express) and Black Echos (first published in 1976) for black music. However, there were no announcements of sound systems even in Black Echos. So I found out about the event schedule by looking at the flyers in record stores and posters on the street.

In sound system events, there were very few white people and of those who were taking pictures. I greeted the organizer at the venue and then took pictures. The strobe lights made me stand out a lot, but except for a few times when I almost got into trouble with drug dealers, I had no trouble at all taking pictures. There was a place called “Frontline” with a very good atmosphere where Jamaican food stalls gathered, but there were also people who were selling drugs mostly to the white customers. I was slapped on the cheek with a knife and asked, “What the hell are you photographing?” But at that time, I was saved by a local friend of mine who interceded and said, “Give this guy a break.”

──Although your photos are black-and-white, they convey an ambience of gaiety.

Ishida: If I were a foreign photographer visiting Tokyo, I would mainly focus on the towns along the Loop Road No.7, such as Koiwa, Akabane, Shimokitazawa, and Koenji. No matter where you go, the center of the city is filled with a variety of well-known tourist destinations and objects, while the suburbs tend to be dedicated to residential areas. In my experience, places that I find interesting are located on the border between these two kind of regions. In Tokyo, that would be areas along the Loop Road No.7. London is divided into concentric zones from the center, and each zone has its own subway fare, but the areas around “Zone 2” are interesting because they tend to have a kind of downtown atmosphere and a large Black populations.

Rediscovering and recognizing lovers’ rock in the 2000s

── Was it this kind of climate that nurtured lovers’ rock music?

Ishida: When I went to London in 1984, the main focus was to photograph the city where the music of Aswad and Linton (Kwasi Johnson), whom I had learned about through “Babylon,” was born, and I myself was not aware of lovers’ rock music at all. In Japan, Janet Kay’s “Loving You” became a hit in 1993, but I just thought that music was a bit flaccid (laugh). On the occasion of Sugar Minott’s Japan tour, I asked him about his lover’s rock hit tune “Good Thing Going” (1981), and he said, “I sold my soul to make that song sell, so you should better listen to ‘Sufferer’s Choice’ rather than that” (laughs). That kind of comment persuaded me that lovers’ rock was superficial music for selling out and the main line was roots reggae and that the core of reggae was to sing about things that happened in the hard reality.

But then, a little before releasing this “Relaxin’ With Lovers” series in 2001, some reggae enthusiasts began to realize that serious music like Linton’s and lovers’ rock were both made by producers like Dennis Bovell and were born from the same background and that they are actually two sides of the same coin: one is political, and the other is just sweeter. I didn’t notice it at all, though (laughs). Japanese enthusiasts were the first to discover this.

Terumasa Yabushita (director of “Relaxin’ With Lovers”): There were a lot of people with the organizer of the event LOVERS ROCK NITE Takashi Fujikawa as the leader, Tsuyoshi “TICO” Toki and Seiji (“Big Bird”) of Little Tempo, who were aware of how good lovers’ rock 12 inches actually were. They also had a dub on the B-side. And you could still buy them dirt-cheap back then.

Ishida: When Mr. Yabushita and his colleagues started Relaxin’ With Lovers, they named the label “15-16-17” after a female lovers’ rock group from the late 1970s. In 2002, the BBC aired a one-hour special program called The Story Of Jamaican Music consisting of three episodes, in which Gregory Isaacs testified that he loved lovers’ rock, especially listening to Janet Kay and 15-16-17. That was in 2002. So the release of Relaxin’ With Lovers was a little earlier than that.

I mean, I didn’t realize until the 2000s that there was a very special musical development of lovers’ rock that was very common within a specific community, but almost no one outside it knew about. I remember when I was in Brixton in 1984, there was a song called “Gimme Good Loving” (1983) by a group called Natural Touch that was extremely popular. It was playing on every sound system I went to. But I’m sure it never reached the ears of the music lovers outside of sound system community who would go to HMV in central London. It wasn’t until the 2000s that I realized anew that that type of music was lovers’ rock. For this exhibition, I remembered that I had shot Natural Touch, and I exhibited that photo for the first time.

───I was struck by your words, saying, “it never reached the ears of the music lovers outside,” but in reality, what was separating the inside from the outside?

Ishida: After all, lovers’ rock is the music of London. One of the things that surprised me when I went to London in 1984 was how thick the wall between whites and blacks was. For example, The Specials are from Coventry, right? Although there were many opportunities for whites and blacks to play music together there and in Bristol and Birmingham in the 80s, there were almost none in London. The only exceptions were people like Adrian Sherwood, Slits, Joe Strummer, and John Lydon, who were all within a close relationship with Don Letts.

Specifically, I was most surprised by the Reggae Sunsplash, which took place on July 7, 1984, at Selhurst Park in Crystal Palace, South London. In addition to a stellar lineup that included Aswad, Black Uhuru, and Dennis Brown, I thought there would be a lot of white people who liked two-tone music because Prince Buster and The Skatalites, who were making their first appearance on stage in the UK, would be there. In addition, King Sunny Ade, who was becoming monstrously popular, would also be there, so I assumed that white people who liked world music would also come. However, the audience was almost entirely made up of black people, so much so that I forgot that I was really in London. I think the reality is that it was challenging for white people to go to black music venues in London. When I talked to people who went to London in the 1990s, they said there were quite a few white people in the Jah Shaka sound system, but that was a change that occurred in the 1990s. In the days of “Babylon,” it was composed of only black people. I am not white, so I was in the most comfortable position. It would have been difficult for a white photographer to take pictures like mine.

However, when “Wembley Reggae Festival 1970,” a massive festival in which Desmond Dekker & The Aces, Millie Small, Bob & Marcia, Toots and the Maytals, and John Holt performed, was held on April 26, 1970, at Wembley Stadium in London, there were quite a few white skinheads among the audience of 14,000 people. There is a scene in the movie Babylon where Blue, played by Brinsley Ford (Aswad), and Ronnie, played by Carl Howman, the only white guy in the Ital Lion Sound System crew, are walking along the south bank of the Thames River. Then Ronnie says something like, “The first time I smoked pot was when I was a skinhead, in ’68 or ’69, I think.” Then he continues, “I saw a concert at Wembley Stadium, in which Desmond Decker & the Aces and a woman singing ‘My Boy Lollipop,’ who was it (Millie Small)?, were performing.”

Sweet, gentle music born out of tough reality

── Are the sweetness and straightforward love-song-nature of lovers’ rock contrast to the harsh reality?

Ishida: According to a commonly accepted theory, lovers’ rock music started with a female singer, Louisa Mark, in 1975. However, there are differing views on how long lovers’ rock lasted. I believe it ended in 1984 or 1985. Even after that, there were many songs whose musical styles resembled those of lovers’ rock. However, despite their stylistic resemblance to it, they were not lovers’ rock anymore because the social landscape has changed drastically. Specifically, just as Japan had an economic bubble in the mid-1980s, England had an economic boom. The south side of London Bridge was developed as a fashionable waterfront area. As far as I know, the club culture exemplified by rare groove and acid jazz was created during that economic boom.

── That sounds interesting.

Ishida: In a broader sense, there were great songs that were just like lovers’ rock musically, though.

──You mean, they were not underpinned by the social landscape, right?

Ishida: That’s right. But it was in the 2000s that this background was first revealed. This trend was kicked off by the Japan-made Relaxin’ With Lovers series and the BBC documentary in 2002, amongst others. Also, in 2011, a British filmmaker named Menelik Shabazz released a documentary film called The Story Of Lovers’Rock. What was depicted in this film was by far the clearest. It clearly states that lovers’ rock is inseparable from the background of sound system culture and the Brixton riots in April 1981 (a three-day riot against a backdrop of severe conflicts between overbearing police and disgruntled local black people, resulting in many arrests). Moreover, Linton was in the film even though the primary focus of it was lovers’ rock music, and Pauline Thomas, the vocalist of Natural Touch, made a decent political statement, just as did Caron Wheeler later. It was nice to hear her testimony because Natural Touch was a lovers’ rock group in the true sense of the word that I experienced in the scene back then.

── In 1984, you must have been bombarded with all kinds of information, both visual and auditory. So I can kind of imagine that you could finally understand what was going on after all these years. You can’t go back to that era, but you can clearly redefine it because you were there. It’s great that you can communicate that.

Ishida: The good thing about photography is that even if you shoot something you are not sure about, you still get an image of it. This exhibition includes photos taken in that kind of situation. For example, when I went to Sir Coxsone International, one of the leading sound systems of the time, I was going to take a picture of the DJ, Jah Screechy, but the two people beside him posed for the camera, intending to be photographed. They later turned out to be Mafia & Fluxy (laughs). You will find out later, even if you don’t know when you shoot it. When I photographed Linton, I was very disappointed because he was wearing tracksuits instead of being dressed in a suit and tie, (which are what we associate with him,) but when my photo was used on the cover of the magazine STUDIO VOICE (June 1996 issue,”Loud Minority”), someone pointed out that that tracksuits were actually from Fred Perry.

── If the ordinary people captured in your photos should happen to find out that their photos were used for the cover of Relaxin’ With Lovers, they will be deeply moved. Your photos will bring back to life the times and atmosphere in which these people lived, along with the music.

Ishida: In my case, the theme of my life is to “take good photographs.” A “good photo” for me is “a photo that I like.” In order for me to like a specific picture, I need to like what is captured in that picture. Therefore, the question of what I should shoot to like that photo fuels my motivation to listen to music. That’s how I move into action. I want to take photographs that I like, and that desire inspires me to learn about various things.

───This attitude of yours and the fact that your photographs have passed through the Lovers Rock era makes this exhibition, as well as this compilation series, so wonderful. An important thing to note is that you did not initially start doing these things out of a love of lovers’ rock. All of these things combined to create a sense of tension. The amount of information is limited, but it is all conveyed.

Ishida: That was just a product of chance. I feel like I was able to be a part of an exciting development.

Yabushita: Mick Hucknall (Simply Red) runs a label called Blood & Fire, which released a compilation called Darker Than Blue: Soul From Jamdown 1973 – 1980 in 2001, which selected 70s reggae soul from a rare groove perspective. The cover featured portraits of black people from the 1970s, and it looked really cool. So when I was looking for something like that for our compilation’s covers, I was impressed by Ishida’s photos in STUDIO VOICE. On top of that, it turned out that he had lived in Brixton around 1984, and I knew it was a done deal.

Ishida: I thought I was shooting the world of Linton and Aswad, but I found out about 20 years later that I was actually shooting the world of lovers’ rock, which is interesting. I only knew Mr. Yabushita once I got involved in Relaxin’ With Lovers. He saw my photos in STUDIO VOICE and decided to have this style of cover. So I have nothing but gratitude for him.

── I would like to ask you what you think about the fact that lovers’ rock now echoes along with your photos from those days in a society where oppression and discrimination are becoming more and more apparent again.

Ishida: Well, looking at it from a broader perspective, as symbolized by the screening of Babylon in Japan last year, people tend to want to see this kind of film again at this time.

Masataka Ishida Photo Exhibition RELAXIN’ WITH LOVERS ~photographs~

Dates: March 25th – April 25th

Venue: JULY TREE

Address: Royal Stage 01-1A, 4-7-27 Aobadai, Meguro-ku, Tokyo

Holiday: Closed Irregularly

Hours: 13:00-18:00 *Subject to change.

Please check the official website and SNS for details as well as gallery holidays.

Admission: Free

Official site: https://www.julytree.tokyo/

Twitter: @JulyTree2023

Instagram: @july_tree_tokyo

Photograpy Kentaro Oshio

Translation Shinichiro Sato