Photographer Ari Marcopoulos has been working on zines for many years as a medium of photographic expression, as a means of organizing his accumulated images and thoughts in a mind-mapping manner, and as gifts for his friends. In June 2023, he published “Zines,” a systematized photo book that includes in one volume the paper-based zines printed between 2015 and 2020 and the zines produced in PDF format during the COVID pandemic. Following the book’s release, he held a solo exhibition, “Against the Current,” at MAKI Gallery in Tokyo.

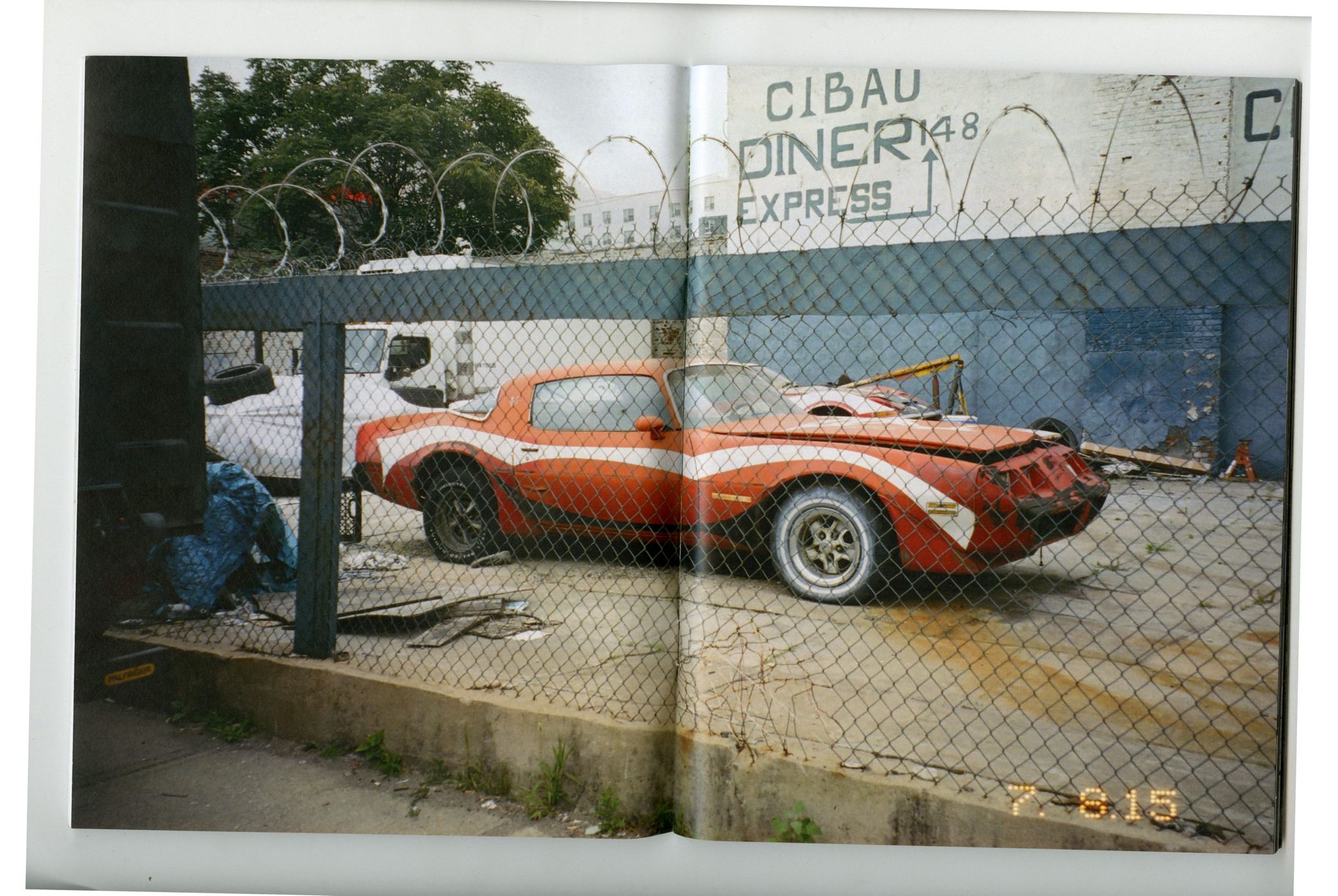

While stepping on the floor of everyday life, he looks with a bird’s-eye view on the situation where individuals and communities in society are exposed to some form of solid power. He reflects this atmosphere in his photographs, allowing us to perceive and consider social and political issues. By framing multiple heterogeneous elements that he himself has found affinity among with his photographs, he gives them a new context and creates a chain of images for the viewer. In fast-paced streets and sports arenas, the thoughtful eyes of Marcopoulos capture the aura and the noise of the vibrant life of athletes and skateboarders aiming high in an earnest manner and the energy of the cultural scene, which is just like a common language.

His photographs, which instantly burn these elements into our minds, are gentle yet intimate with cinematic narratives, evoking an intuitive resonance in the hearts and minds of the viewers. In this interview, we asked him about the background of “Zines” and “Against the Current,” as well as the thoughts he puts into his photography.

Ari Marcopoulos

Ari Marcopoulos is a US-based photographer born in the Netherlands in 1957. He moved to New York in 1979 and apprenticed to Irving Penn following his work as an assistant to Andy Warhol. He is known worldwide as an artist whose work crosses the boundaries between the American subculture such as skateboarding, hip-hop and the terrain of fine art. In particular, he has been successful in the publication of numerous photo books, zines, posters, and other printed matters. His work is included in the collections of the Berkeley Art Museum, Detroit Institute of Arts, Winterthur Museum of Photography, New Orleans Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Recent solo exhibitions include “Upstream,” Kunsthalle Sankt Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland (2022) and “Time Motion,” Archive/Project Space, Pittsfield, MA (2021).

Marcopoulos has created 200 books and limited-edition private magazines, including Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (Aperture, 2023), Polaroids 92-95 (CA), Polaroids 92-95 (NY) (both DASHWOOD BOOKS, 2020), Epiphany (IDEA, 2016), and Rome-Malibu (Roma, 2016).

Instagram: @ari_marcopoulos_official

“Zines,” a projection of a reality dismembered by historical incidents and the internal and external changes of self and others.

–What inspired you to compile Zines into a book, given your analytical use of each medium–photography books, exhibitions, and Zines–in terms of their scope and effect?

Ari Marcopoulos (Marcopoulos): I came up with the idea of creating “Zines” during the pandemic. At that time, copy shops and bookstores were closed, so I made zines in a PDF format. Since there was no telling when the pandemic would end, I would send my zines as PDF data to friends in New York and artist friends overseas, instead of just waiting for a more favorable situation.

After the situation had gradually calmed down, I started to think it would be important to keep a record of the pandemic chronologically in telling the stories of my own life and other people’s lives back then. I approached the publisher Aperture with a proposal to publish a photobook out of PDF files. They loved my idea and were willing to publish it, so I started to work with a designer, my longtime collaborator, discussing how we could frame the book.

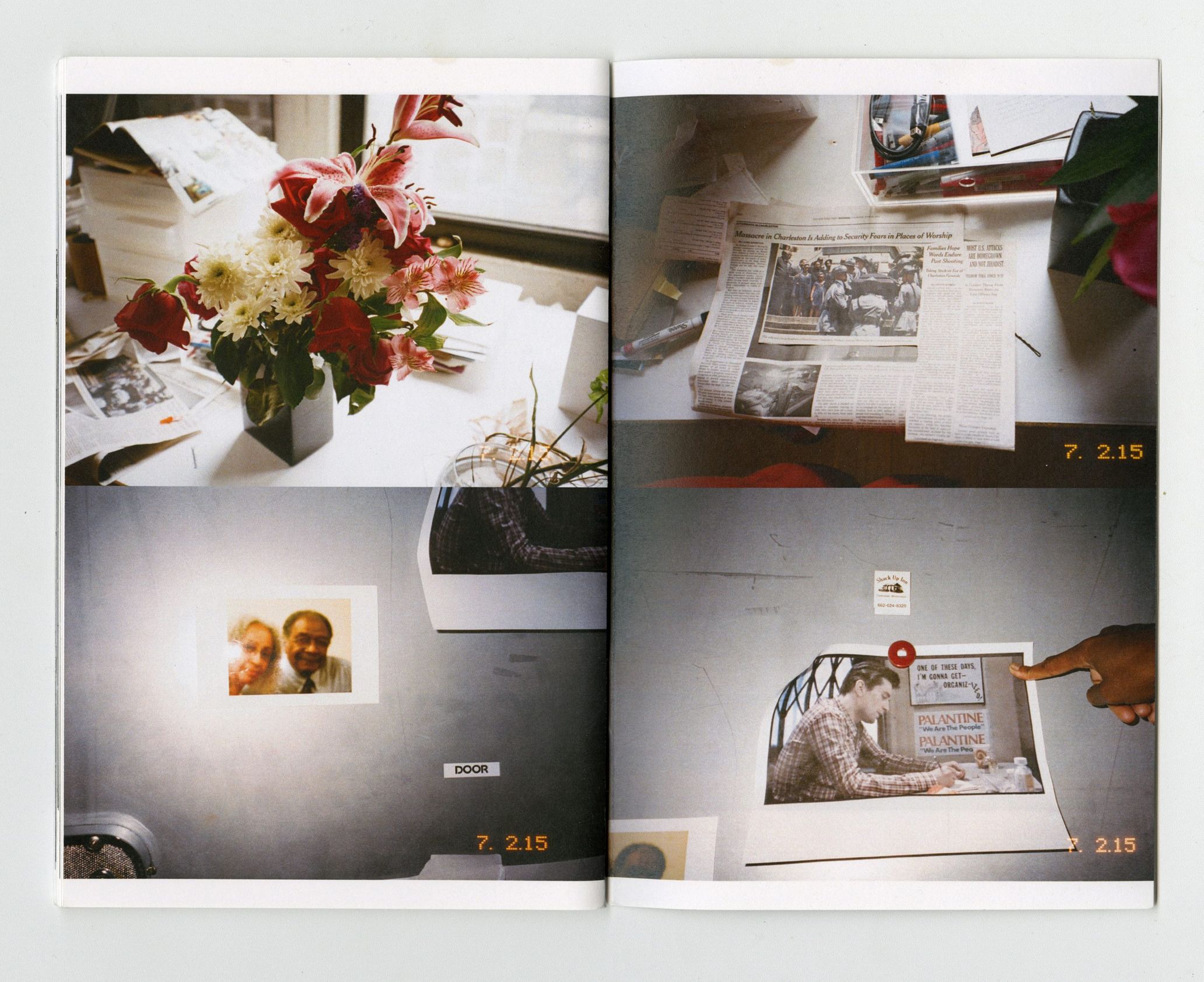

The book is divided into two sections: the first half consists of scans of paper-based zines printed between 2015 and 2020. You can actually see the staple binding in the center of the spread. The second part is composed of PDF photographic images printed on a black background, which looks more like a typical photobook.

–The PDF section provides us with your point of view on the everyday life that has been disrupted by historically notable events creating “disjuncture (pre and post periods),” such as the pandemic and Black Lives Matter. From what perspective did you take these photographs?

Marcopoulos: I have always been interested in social and political issues, but I am not a news photographer or journalist, so I do not take photographs that get at the core of the issue. Rather than dealing with the subject squarely, I think my approach is to address the issue in a roundabout way, as when I photographed the protests triggered by the assault of a black boy by a young white man in the 1980s, for example.

I often take photos of the cover photos of “The New York Times,” which deals with important social issues of the day and complex situations that are difficult to resolve, so in some ways I am capturing society through these photos.

On page 204 of “Zines,” there is a photo depicting “The Raft on the Medusa,” a work by 19th century painter Theodore Gericault, placed right next to “Five Car Stud,” a book of Edward Kienholz’s installation. (*1)

As the American writer Maggie Nelson mentions in her preface to “Zines” (*2), I am not focusing directly on social-movement-oriented expressions through photography. Still, I believe that the viewer can receive something from my photographs, interpret them with their imagination, and gain insights. In my work, of course, I occasionally take commercial photos, but basically, I shoot what I really want to shoot, rather than taking photos that people expect me to.

–The photos taken during the pandemic show individuals in the almost unpopulated city of New York for the first time in history, in a situation where death is very close at hand. Unlike journalistic photos, they allow us to see the everyday life that has changed drastically, with a time stamp through your eyes. The zines produced after the pandemic are based on memories shared worldwide and provoke different reactions from viewers than those caused by zines produced before the pandemic, which have more intimate nuance. How do you perceive the photos before and after the pandemic?

Marcopoulos: The pandemic was a shared experience worldwide, although individuals cope with it differently.

Before the pandemic, I thought viewers would see something “familiar” for them in a photograph. For example, suppose I took a picture of a certain family. The viewers may look at the photo and think of their own family. Or a photograph of an injured elbow of a child who has fallen off a bicycle may remind viewers of their own child or their own childhood. I believed that this was what photography was all about.

Since the pandemic outbreak, the inside and the outside of our lives have been divided, and me and my partner have been isolated from the outside world, lapsing into a very introspective state of mind. We came to work slower than we did before and to take fewer photos.

Black Lives Matter-related protests were happening in various places at the time, but I no longer went to the sites to take photos as I used to but rather took photos of things that caught my attention while walking around the neighborhood. At a basketball court near my place, a guy wore a face mask while playing with two balls, which looked surreal.

Basically, I see photo books and videos as something that creates a cinematic feeling through a series of images. After the pandemic, I felt like the cinematic flow of time in the photobooks slowed down.

One day, I came across a school graduation ceremony taking place outdoors. It was the first positive event I had experienced during the pandemic, and I took several pictures. In the past, even though I would have found this event to be a pleasant experience, I probably would not have found such profound meaning in it. The pandemic was the catalyst that led me to stop by and photograph the event, which was a significant change for me.

The work is completed and cycled by the audience

–You have created a number of zines so far. What kind of people do you expect as an audience? Also, what has been the most gratifying reaction from people who have read your zines?

Marcopoulos: I don’t have a specific target audience in mind, but I would like the younger generation and people who try to be young at heart to see them. The exhibition at MAKI Gallery in Tokyo was visited by young people who have probably never been to a gallery to see art pieces before. They may not even buy my books, but there may be many young people who get to know my name by chance and come to the gallery with their friends. I feel a work presented publicly is completed by audience, which works just like a cycle.

Usually, when I make a zine to sell, I bring it to “Dashwood Books” in New York or sell it through distributors and stores in Japan, Australia, and England. But apart from that, I sometimes make zines as personal gifts. For example, when I travel with my partner, I make one or two copies of a zine about the trip.

One time, a guy who lives nearby told me that his brothers were coming all the way from Tennessee to celebrate his birthday. Later, I saw people in the neighborhood that I don’t usually see, so I took their pictures and counted how many people were in the printed photos, and there were 14 of them. I made 14 copies of a zine with those photos and gave them to that guy.

A week later, when I went to my favorite barbershop in the neighborhood, I was told that the guy to whom I gave my zine was delighted and proud of the zine I gave, saying, “Ari had made a zine for me with my brothers’ photos.” The most gratifying reaction to my zine was that the person to whom I made the zine and gave it as a gift was pleased and received it as a meaningful gift.

— By making a photo book out of zines that were intended to be given to specific people, the audience for the zine has expanded even further. How do you think this transforms the photographs?

Marcopoulos: I usually make a zine on a different theme each time, but mixing each subject in one book gives it an archival quality, a study, or a kind of research that shows the art practices that are important to me in a comprehensive way. The zine I have made for a very limited period of time will have a completely different meaning by being contained in a single book, as it can be a part of representing my practice to date systematically.

A Solitary Spirit Engraved by Concentrated Images and Sound

— An exhibition as a visual medium allows for the expression of a “video work,” which is different from a photobook or a zine, that boosts the power of the images and delivers it to the viewers effectively. The video work “THE PARK” (2019), which was shot by you with the determination to accept all of reality in front, also reflects the vital noise that humans emit, and matches very well with the music of jazz. At your solo exhibition held at MAKI Gallery in Tokyo from June to July this year, “Butter,” a video work capturing snowboarders sliding inside a halfpipe, was also shown. Please tell us about the expression you are exploring in your video works.

Marcopoulos: “The Park” is a 60-minute film shot with two fixed-point cameras. For the sound, we had the option of using real sounds from the location, but we ended up having pianist Jason Moran improvise to the video and record it for the soundtrack.

On the other hand, the key for this snowboard video piece, “Butter,” is “a rhythm of rising and easing tensions,” consisting of the noise the skateboarder makes on the halfpipe and the silence that comes at the moment of air. The air suspends when the rider is in the air, and the tension comes back. I found this 30-second loop interesting.

The “Butter” project took six years to realize. I planned and chose carefully the best skateboarders and filming locations for this 30-second clip. The halfpipes are usually located in snow resorts, where hotels and other buildings can potentially be included in the footage. However, after careful location research, we filmed in Saas-Fee, where the majestic Swiss mountains provide a stunning backdrop. The halfpipe itself gives the impression of sculpture or land art. I thought the lighting was a significant factor for this piece, so we shot it in the early morning, which successfully worked to create a mystic aura emanating from the sunlight.

Also, I call the movement of athletes “dance,” and this time, as in Ozu’s film, I shot in a dry, fixed-point style with the camera barely moving to further emphasize the “dance” in the rhythm of rising and easing tensions.

Also, the sound of the video was bouncing to the walls of the gallery space, sometimes echoing like a huge noise, and other times quiet and silent. It can be seen as a kind of sound art rather than a video.

— In snowboarding, which is performed in the formidable snowy mountains, there is a contrast between the existence of man and nature, and the ambition and enthusiasm of man to conquer nature, as seen in some of Werner Herzog’s films. What was on your mind at the moment of shooting? Also, was there any difference from photographing people skateboarding or playing basketball on the streets of New York?

Marcopoulos: It is understandable that my work shot in the snowy mountain reminds you of Herzog’s films, and for the work “Ayumu,” I had in my mind the image of a painting by Kasper David Friedrich, a German painter from the 19th century. Kasper painted small and silent human figures that stand in majestic nature. In that sense, the location was essential for that work.

Athletes compete in physically extreme challenges and amidst danger. In a sense, the glimpse of their challenges to overcome nature inspired me a lot to shoot snowboarding works.

When I go into the mountains to shoot, a strange sensation arises. I began to enjoy being in the peaks themselves and to feel strongly how small we humans are in contrast to the scale of the mountains.

Skateboarding and snowboarding are similar in that they share common movements: riding on the board and sliding sideways. Also, riders focus on their bodies and movements in both sports. The mentality of skateboarders is something that I am strongly attracted to when I photograph them. With the common interest of skateboarding, the distinctions between age, race, gender, and other social categories disappear. When you go to a skate park, there is a wide variety of people from all walks of life. This is an exciting point for taking photographs.

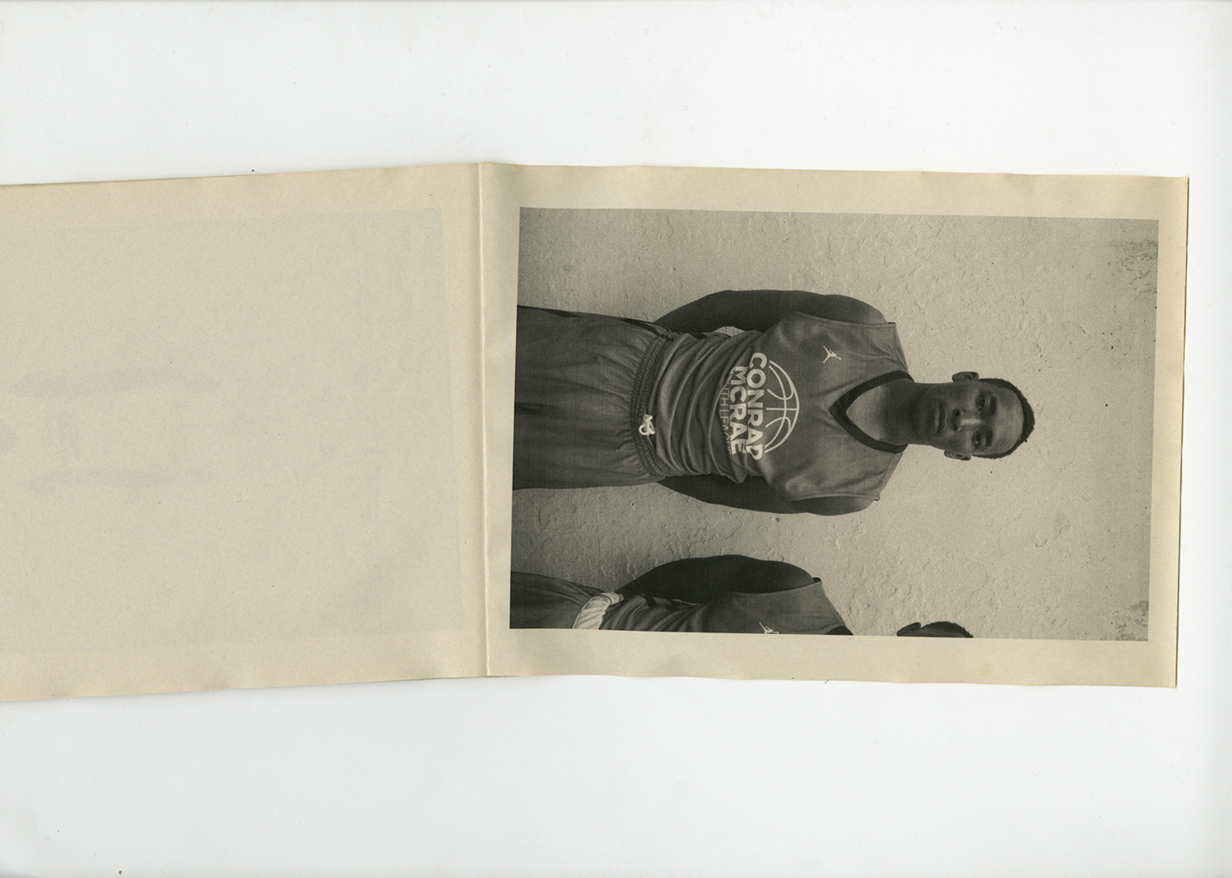

Whether it is snowboarding, skateboarding on the street, or basketball, I photograph the culture rather than individuals as my subjects. I don’t focus directly on the beauty of the body, although there is an aspect of showing the beauty of the body and movement through my photography.

I have to give it all my got to concentrate all my thoughts on photographing people who are “passionate about something and accomplish things with enthusiasm.” This mentality is something I share with them.

–During your last visit to Japan, you stayed in Tokyo and Kyoto, did you find anything that you wanted to photograph?

Marcopoulos: That was my second visit to Kyoto, which was a delightful experience. Kyoto is very different from Tokyo in how the city is built, with streets organized along grids and many old things remaining. I took pictures of temples and other historical buildings, new architecture, and people training kendo.

I was also impressed by the wonderful works in the exhibition “Re: Startiline 1963-1970/2023: Sympathetic Relations between the Museum and Artist in the Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition” at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto.

It would also be interesting to revisit the Raku Museum and discover how the Raku pottery tradition has been passed down through taking photographs. Next time, I would like to find a place to live and stay in Kyoto for two to three months.

1. “The Raft of the Medusa” is a painting that journalistically depicts the actual 1816 shipwreck of the French navy ship Medusa. The French commanding officers and other dignitaries used the lifeboats exclusively at the time of the shipwreck, leaving the 149 crew members adrift on a roughly built raft. Most of them died in the 13 days before the rescue; even 15 survivors lapsed into physically and mentally extreme states. Géricault interviewed survivors and conducted extensive observations of human bodies in hospitals to realistically depict the horrors of the starvation, madness, and despair that trapped the people in the incident. “Five Car Stud” is an installation work that consists of a realistic diorama and life-size figures and automobiles depicting the lynching of a black man who was chatting with a white woman at night by white men.

2. Maggie Nelson writes, “Although it is seemingly a photograph capturing the juxtaposition of disparate cultural objects, the combination of these two works depicts a complex structure of white and black bodies subjected to suffering and violence, which evokes the relationship of Géricault and Kienholz as white artists, to black images, historical violence, racist protest, anti-slavery abolitionism (summary).”

Interview Akio Kunisawa

Translation Shinichiro Sato(TOKION)

Cooperation twelvebooks, MAKI Gallery