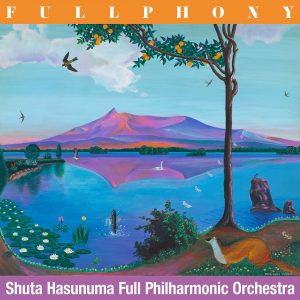

As a solo artist, Shuta Hasunuma creates a diverse range of music, from acoustic to electronica. He has gone beyond the narrow definition of “musician,” and works on art pieces and exhibitions that center on “sound” in a free-spirited way. Ten new members have joined his pop orchestra, Shuta Hasunuma Philharmonic Orchestra (“Phil”), and he released a new album titled Fullphony with Shuta Hasunuma Full Philharmonic Orchestra (“Full Phil”) with 26 members on August 26th (the CD and analog LP will be released on October 28th). Also, the album cover, which features Tadanori Yokoo’s artwork, is impactful. The A-side of the album has rich, interwoven harmonies comprising a plethora of unique sounds, while the B-side has Shuta’s remixes of all the songs on the A-side. We spoke to Shuta regarding what Phil means to him and why he added more members. Further, he talked about the album-making process and his philosophy on creating music.

Phil is a project for working with other people

—First, could you talk about why you created Phil? How did it come about?

Shuta Hasunuma (Shuta): I got my start in music by making electronic sounds with my computer and field recordings. I would then add in melodies and harmonies. Those sounds turned into a variety of genres, such as music with electronica or J-pop elements. I had been creating music by myself for a while.

But I discovered it was impossible to make an entire record by myself when I was at the stage of releasing one. Without the help of people working at the label, alongside other people, I couldn’t make something that the listener could enjoy. I’m technically a “solo” artist, but I could only make music with everyone’s help. That is what I realized by releasing music.

—You realized how important it is to have other people via your music career.

Shuta: Yes. I also thought, “how could I perform the music I made in a live setting?” I concluded that I wanted to express my music by playing with other people instead of using my laptop or playing solo. At first, there were six people, and then more people joined until it turned into Phil. It’s a project where I work with other people through my music.

—What did you gain from working with others in Phil?

Shuta: There are members with more experience under their belt, so I was inspired musically, but I gained something bigger than that. Everyone has a unique background in Phil, and as I got to know each person’s way of living and thinking, I thought, “music comes not only in one shape but in many shapes.” It has been about ten years already since Phil started, but in hindsight, there were a lot of different discoveries.

For instance, the guitar only makes a sound when a person touches it with their hands, right? It may sound simplistic, but a sound is born when a player makes a movement based on their will. There are reasons and messages behind why the things around us make the sound they make. Thinking about that makes me appreciate how deep the world of music is. I might have never thought this if I only worked on field recordings as a solo artist. I want to apply the epiphanies I had because of Phil to the things I create and deepen my thinking even more.

Full Phil was born to transform the relationships between members

—Since the release of Anthropocene (2018) with Phil, you garnered ten more people and became Full Phil with 26 members in all. Could you talk about how and why that came to be?

Shuta: When we were making Anthropocene, I had already been thinking about increasing the number of members, and so I spoke to the rest about it. Regarding creating music, I don’t want to do the same thing twice. To do something new, you have to change, even if that means destroying existing things or ways of thinking. I held an audition to get ten new members and created Full Phil to do that.

—Upon recruiting more members, did you have an image of what sort of instruments you wanted?

Shuta: More than a sonic change, I wanted to have a change in the circumstances. It was important for the relationships between each member to change by having an additional ten members. It wasn’t like, “I need this instrument for the next step in my music.”

—You made your newest album was in 2018, the same year you released your previous album. Full Phil’s first performance, Fullphony, was done in the same year. Taking into account the chronology of events, was the mindset you had with Full Phil a continuation of the one you had when you made Anthropocene?

Shuta: In terms of the chronology and content, it was an extension. With Anthropocene, I kept each member’s character in mind and made the songs according to who they are. For example, instead of being like, “Euphoniums make this sort of sound, so I’m going to think about the phrases and melodies according to that,” I was like, “Gon-chan (Tomohiko Gondo) plays the Euphonium, so the melody he likes to play is probably like this.” As Phil, Time plays – and so do we, our first album created based on a collective idea was the first phase, and Anthropocene, made with each member’s character in mind, was the second phase. And the final form of that second phase is Fullphony.

Intuitively wanting Tadanori Yokoo’s work on the cover

—Tadanori Yokoo’s 70s piece, “Onuma and Komagaoka” is used on the cover of your latest album. Why did you choose this? Was there a catalyst for it? Shuta: When we finished recording the album, I intuitively was like, “I want to use Tadanori Yokoo’s work for the cover, no matter what!” (laughs). I didn’t have a clear idea of which image I wanted to use for the cover, but the existence of Tadanori Yokoo as an artist popped up in my mind. I went to his gallery and looked through every single material and book of his. The one that caught my eye was “Onuma and Komagaoka,” which is included in his Landscape Paintings series. I had the chance to visit his exhibition in Kobe a long time ago -probably around 2013- and I encountered Landscape Paintings there. That memory was fresh in my mind, and so I think that is why I was like “this is it!”

—So, the cover was born from that gut-feeling encounter you had. The painting’s scenery depicts different animals in lush, grand nature and it has no people in it. That gave me the impression that the cover was one form of a “post-Anthropocene” world.

Shuta: I discovered this after a while, but Landscape Paintings is a series of paintings he did in his studio after he traveled all over Japan. He painted the sceneries imprinted in his memory in a fictional manner. I don’t know what his interests or thoughts were in the 70s, but the paintings have a Sci-fi feel to them. Perhaps he drew landscapes that might exist in the future, one which has no people in them. It’s not like I intentionally titled the previous album, Anthropocene, and used an art piece that matched that theme for the sophomore album. But I think the two connected in my mind subconsciously somewhat.

Yokoo-san designed the back cover specifically for this album; it’s based on the front cover. The back cover has no words, animals, or plants. I think he took the present into account and added his own new meaning to the design.

—On the cover, lotus flowers are floating atop the marsh. It’s like your surname, Hasunuma (“Hasu” means “lotus” in Japanese, while “Numa” means “marsh” in Japanese).

Shuta: I didn’t choose that painting because it’s like my surname (laughs). I have a rule for Phil’s album covers; “landscape painting with no people in it.” I narrowed down the options to 4 potential covers, and the one that I got inspired by the most was this one. The lotuses were coincidental. Including this occurrence, I’ve started feeling like my interactions with Yokoo-san was a serendipitous fate.

Synchronous and asynchronous harmonies made of unique, diverse sounds

—You released the first song, “windandwindows” as a solo artist, and it is also the title of your collection of previously unreleased songs, released in 2018. Why did you record the same song for Fullphony?

Shuta: “windandwindows” is also the name of my podcast I used to host around ten years ago. Atsushi Sasaki, the CEO of HEADZ, which I used to be signed to, came up with it. I liked the meaning and thought it had a nice ring to it. I’ve used the same title for the track I made for Roppongi Hills and a collection of unreleased songs. It’s an integral word that I can’t cut off from my work. “windandwindows” on this album is the sonic manifestation of the word’s meaning and feeling. I mentioned how this album is the final form of Phil’s second phase, and I feel like this song is a compilation of both men’s and women’s vocals.

—This is slightly off-topic, but could you talk about why you have increasingly released more vocal tracks compared to before?

Shuta: While I was trying to create music with a focus on originality, I thought, “I’m going to incorporate my voice as one element.” After all, the sound you make with your physical body has the highest level of originality. I guess it’s obvious (laughs). I write my lyrics and sing, but I am not a singer-songwriter. I reckon for singer-songwriters, the lyrics and songs are tied to each other, and those things are inseparable from who they are. For me, the lyrics and song are separate. I think I am a composer at heart. If I feel like my voice needs to be included in the music I want to make, then I would sing. That’s how it is for me.

—Your voice is an instrument that you, as a composer, manipulate. This album is divided into four musical movements: “Difference – Greeting – Gush – Face.” The first movement is quiet, and the scattered sound is memorable.

Shuta: When I thought about the beginning of the fourth musical movement, I wanted the sounds to accumulate one by one instead of having all 26 people play at once. Simultaneously, I had this image in my head where the beginning is asynchronous while the next part becomes synchronous as the sounds harmonize. That’s why I asked each member to play to the beat of their own heart for the first movement. It’s supposed to sound scattered.

—A diverse range of sounds and rhythms emerge in the third movement, but there is no trace of excess or exaggeration there. When you compose songs, what sort of thing do you keep in mind?

Shuta: Regarding Phil’s songs and arrangements, I try not to “create a focus.” It’s not like I say, “alright, this is the focus!” and add onto that or get everyone to play one melody together. I make sure everyone is independent as much as possible.

—I felt like the themes of the fourth movement was “to meet and to part,” “to accumulate and to separate,” and “synchronism/asynchronism,” which you touched on.

Shuta: I make lyrics the way I make field recordings. Like, I verbalize how people or objects present themselves on their own accord… I write lyrics that way, so I think that’s why “synchronism/asynchronism,” “to meet and to part,” and such come out naturally. These things are always happening right in front of our eyes. I made most of the lyrics in the fourth movement when I was walking outside. So, it feels like they were field recordings.

— Fullphony includes remixes of “windandwindows” and the fourth movement. What’s behind them?

Shuta: I made the remixes during the stay-at-home period of this pandemic. I looked back on the recordings we did as Full Phil last spring and wanted to delve into what it means to be an ensemble. And so I made remixes. I started by cutting down the dozens of WAV files and making them more minimum. It was the same as Yokoo-san’s process for the back cover; we both removed objects from the work. It surprised me to realize that we had a similarity in this regard too. Yokoo-san made designs based on taking away elements during the pandemic- this is what I came to discover.

—You have a plethora of methods and tones in the remixes, such as analog synths with fluid and ambiguous pitches and classic drum machines.

Shuta: I first started by stripping it down. Of course, I added my flavor of sounds additionally by using synths, samples, and so forth. I wanted to make remixes that weren’t normal or basic. I kept a sense of coherence without sticking to one genre. I hope people could enjoy listening to the different feel that B-side has, in contrast to the A-side.

—How do you want Phil to evolve after having completed Fullphony? Could you talk about your outlook towards the future?

Shuta: I believe I constantly have to break away from boxes like, “Phil’s music should be like this” or “this is how I make music.” In August, we had an online show called “#PhilAPISpiral,” and most of the songs we played were new. Both the members and I felt satisfied, and the people that watched it gave us comments like, “I felt a new sensation.” I talked about how Fullphony is the final form of phase two, but I felt like we could move onto the next phase, after this performance. With this satisfaction firmly on our chest, I hope we could prepare for the winter months and do something new.

Shuta Hasunuma was born in 1983 in Tokyo. His work is prolific; he has worked on music releases, domestic and international concerts as Shuta Hasunuma Philharmonic Orchestra, film scores, music for theater and dance, and music production. In recent years, he has applied his musical composition skills to various media forms such as videos, sound, and three-dimensional installations. Shuta Hasunuma holds solo exhibitions and other projects.

http://www.shutahasunuma.com/

Twitter: @Shuta_Hasunuma

Instagram: @shuta_hasunuma

Photography Tasuku Amada

Transration Lena-Grace Suda