Saho Maeta, who heads “menmeiz”, is a curator of the kawaii culture from different countries and shares her work online. Nowadays, the kawaii culture, which originated in Japan, has spread to countries across the world, and started to develop its distinctive style. In recent years, we started to see increase in the number of trends from South Korea and Chinese booming in Japan. The impact on young people is particularly significant. We asked Maeta, about how Japan’s kawaii culture is developing in other countries in the world, and how it influences Japan.

The Goal is to Disseminate the “Transnational Kawaii” Culture

—— What does “menmeiz” mean? I have never heard the word before.

Saho Maeta: Originally, I was interested in Chinese culture. I was looking for a word to describe kawaii in Chinese. At that time, moe, which originated in Japan, was popular in China.

In that context, young women, who cosplayed in anime outfits were called menmeiz. I found it interesting, that the moe culture from Japan was exported to another country and became popular. That is where the project’s name came from. And, when it’s written in Chinese characters, I think it evokes kawaii-ness from the way it looks.

—— When did the project start?

Maeta:I came up with the concept around 2017. In the beginning, I thought of developing an idol (aidoru) called “menmeiz,” but it didn’t work out, and I started it as a project.

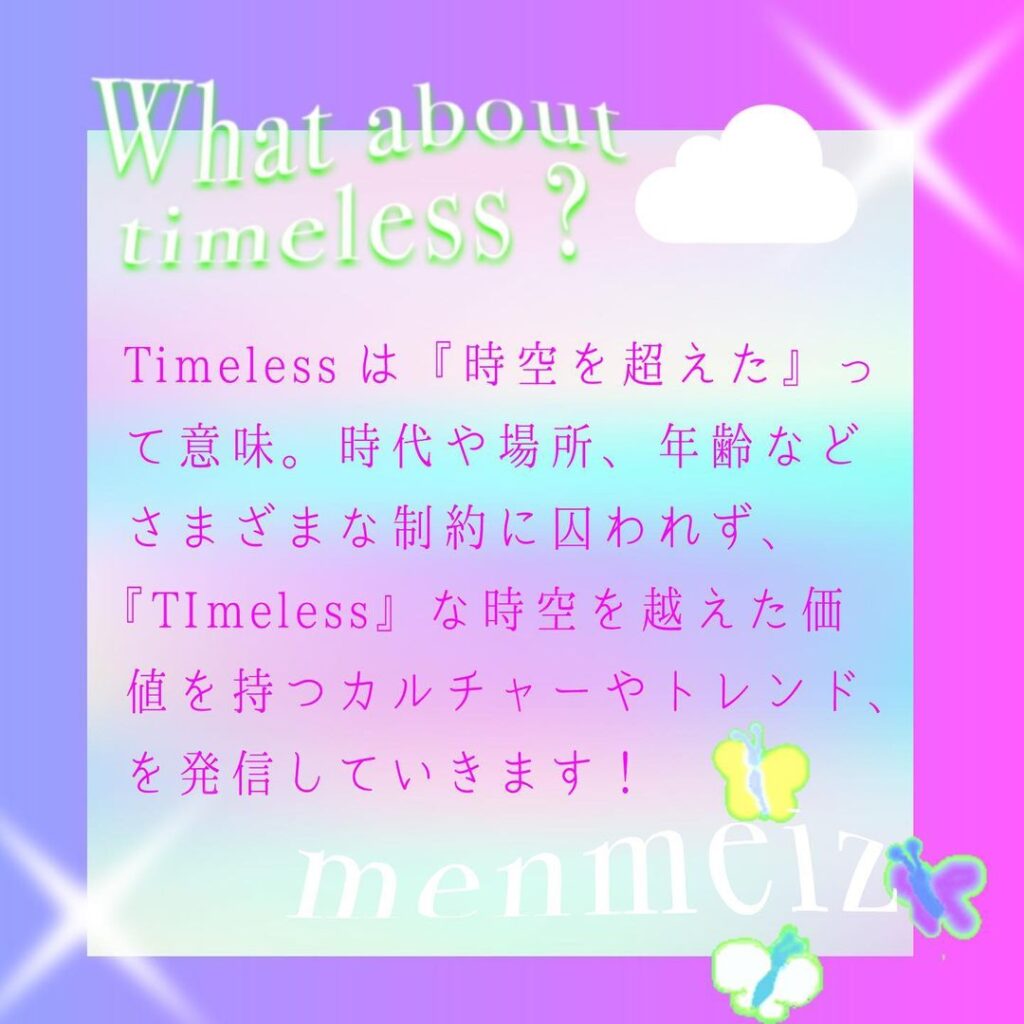

The goal of our work is to turn the kawaii culture borderless, genderless and transgenerational; it is to create a transnational kawaii culture. We collaborate with influencers and artists in Japan and overseas, organize pop-up events, and use social media to disseminate transnational kawaii culture.

The project was launched in June 2019. We organized our first pop-up event at Beams Japan in Shinjuku. At that time, the event concept was “A Fancy Shop in 2050”. As curators, we picked 10 sets of artists who were inspired by Japanese anime and fashion, and by South Korean pop culture. We sold the artists’ work on consignment. After that, we organized pop-up events at places such as Laforet Harajuku, Hankyu Department Store Osaka Umeda Main Store, and Shibuya Parco. We gradually started to work with artists from Japan and overseas, and launched original products. Lately, we are involved with creative work that reflects the worldview of “menmeiz”.

We sell products on our website, and they are mainly imported from abroad. But, we also added some original products. As for selling products, we have not been able to do as much as we wanted due to the pandemic, and we would like to grow that business this year.

——What kind of people come to your pop-up events?

Maeta: They are mainly female high-school students and college students. I feel that “menmeiz” is supported by young women, who assert their individuality. They probably go to art schools or schools where you learn about fashion, such as the Bunka Fashion College. Every time we have a pop-up event, we make sure to create an area that is photogenic. In fact, a customer who came to the store on the opening day, tagged the area on her photo, and customers showed up after seeing it. The sales of small items including earrings and bags were very successful. Stickers and zines made by the artists were also popular. And, some of the odd toys from China did well, too.

——Do you mainly sell your products on the website and at the pop-up events?

Maeta: Well, I had tourists from abroad in mind initially, to sell the products to, but that idea went away because of the pandemic. I would like to sell products overseas, especially in China, but I have not been able to get to that point yet.

However, this Summer, we are planning to open a store in Kyoto. This is not a “menmeiz” store. I am working with four friends to open this store, and it will carry some “menmeiz” products. We reach out to our customers via our website and social media, but a physical store will be an opportunity for our fans to have tangible experience, and we hope that this will lead to expanding our fan base.

Nowadays, D2C (direct-to-consumer) business is booming, and many businesses no longer have a physical store. However, the advantage of having a store is the ability to communicate your worldview to the customers, and build a community. I felt that strongly when we organized pop-up events. We, as “menmeiz”, are very intentional about nurturing our unique worldview, and having a physical space will help us achieve that.

——Why did you choose Kyoto?

I used to live in Kyoto when I was in college, so I know the area well. Kyoto is a historic place, but it also has strong subcultures as there is a large number of college students. This season, we are featuring “timeless” as the concept of “menmeiz.” Kyoto is a timeless place. Once the pandemic is under control, we will see a surge of visitors, and there will be an expo in Osaka in 2025. I think that the Kansai region (Western part of Japan) is becoming interesting.

Looking for “kawaii” outside of Japan

——I see that you collaborate with a wide range of creative people not only from South Korea and Taiwan, but also from France, Canada, and Serbia. How do you find them?

Maeta: We basically use Instagram to look for them, and when we find someone that we think is good, we get in touch with them directly. We don’t speak the language, so we translate our texts and start corresponding. Then, we ask if they would be interested in participating in the pop-ups. That is how it works.

——When you look for people, do you use any particular keywords?

Maeta: We try to identify the right person without counting on keywords. For example, we were connected to artists in South Korea, who were doing artwork for Night Tempo. That led to connecting to artists in Taiwan. And, when we started looking at the followers for these artists, we realized that a lot of them liked Japanese anime. So, we kept on digging. We use Instagram a lot, to find the right connections. We came across with a community of artists on Instagram, who were working together to draw paintings. It’s quite interesting.

There are countless hashtags related to #kawaii, and when we started to look into that, we found many posts from people based in Europe and the United States. They have posts blending South Korean or Harajuku style elements. It’s so interesting. On the other hand, the kawaiiculture that the Japanese people have in mind stalled, with the image of Harajuku 10 years ago. If you don’t get fixated solely on the kawaiiculture in Harajuku, you will realize that it covers a wide range of things, and there are many people in this world, who probably would feel the same way.

——Who drew this painting that symbolizes “menmeiz”?

Maeta: Moe, who is an illustrator, drew it. She also runs the “menmeiz” with us, and has contributed her work to recent Instagram posts. While her work has the looks of anime from the 1990s to 2000, it incorporates her taste in contemporary fashion, and an ironical view based on her artistic sensibilities. It makes her work interesting.

——In the “menmeiz” video, you feature a man with makeup. Was the intention to make it genderless?

Maeta:He was a friend of the female model, and she brought him along to the shoot. It was the model’s idea to put makeup on him. While filming the video, she asked him if she could do it. It was something that was not planned beforehand. It just happened spontaneously as they thought it was a cool thing to do.

How to Disseminate the Evolving Kawaii Culture

——You are very familiar with the trends in China and South Korea. Do you think the young people in Japan are influenced a lot by the trends in these countries?

Maeta: They are particularly influenced by the trends in South Korea. About four years ago, if you were a fan of an idol in South Korea, you would try to imitate the trends in South Korea. Nowadays, everyone is looking at the trends in South Korea, as anything from there is considered fashionable. And, it’s part of the mainstream trends. The K-Pop idols are created the same way the world luxury brands were established. The setup itself is very different, compared to the J-Pop idols. The K-Pop culture has become mainstream in Japan recently, and the young people in Japan, who are keeping an eye on it, have a better understanding of their creativity.

——How are things in China?

Maeta: In China, the Gen Z is dominant, and the trends are segmented in many groups. Of course, there are many people who love the K-Pop idols, and there are many followers of Japanese anime. Both K-Pop and anime are from abroad. Since the Chinese are aware that these things are not vernacular to them, they easily modify the style to their likings. Anime-based cosplay, Lolita fashion, female high school student uniform, and Hanfu are all quite popular. As for female high school student uniform, the Chinese see it as regular clothing worn by girls in Japanese anime. Therefore, they wear it just like regular clothing. That didn’t happen in Japan, but this trend developed in China.

——In that way, do you think that unique kawaii culture is developing overseas?

Maeta: Exactly. It’s significant in China, but it is happening in Europe and the United States. What I am trying to do here, is to extract that uniqueness, and bring it back to Japan again. The culture that was exported the most from Japan to overseas was anime and manga. Anime has many viewers in Europe and the United States, and among China’s Gen Z. The global success of South Korean pop culture is a role model. I think Japan can harness the anime culture, and strengthen content for the overseas market. In the mid-2000s, when the government was pushing the Cool Japan measures, the social media were not as developed as today. Now, we take it for granted that social media are transnational. For example, Sailor Moon has fans all over the world. As for “menmeiz”, we are highly aware of the worldview and values created by anime.

——Do you think that the Japanese can empathize with the newly developed kawaii culture?

Maeta: I think they can really empathize with it, and the customers who come to “menmeiz” are really into it. I think the kawaii culture in Japan is not as empowered as it used to be. I was talking to a young woman from Singapore, and was struck by what she said. She said, ‘The kawaii cultures in Harajuku or South Korea are not that different.’ Now that the word kawaii is so common in the world, I decided to curate the kawaii culture, as I have a thorough understanding of the kawaii culture in Japan.

——Are you planning to disseminate your findings to the world?

Maeta: Exactly. First, I want the young people in Japan to resonate with the current kawaii culture. In my opinion, the current kawaiiculture is about having the girly mentality, while in the past, it was focused on moe. Now, it is more about voicing endorsement for anything that is kawaii. I feel that there is a stronger sense of individuality, and I want people all over the world to understand that mentality.

As for “menmeiz”, I hope I can extract the kawaii style of the era, and create a community with people who understand the mentality behind it.

Saho Maeta

Maeta (b. 1990) is the head of “menmeiz,” and is a curator of transnational kawaii culture. She also works as an editor for girl culture-related topics. She became independent after working for a design firm and a management firm. Her overall focus is on youth trends and trends in China. She is also an art director for music bands and idols, including Silent Siren, Babysitter, and Rikako Ooya.

https://menmeiz.com

Instagram:@menmeiz

Twitter:@sahohohoho

Photography Yohei Kichiraku

Translation Fumiko Miyamoto