Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes (Droste) is the first-ever original feature-length film by the theatre company based in Kyoto: EUROPE KIKAKU. It is a sci-fi movie that takes place at a café in a building located in the company’s home ground—Nijo, Kyoto—and conveys the turmoil arising over the ‘time-tv’, which projects two minutes in the future; during the production, the company had started crowdfunding for the film and reached a whopping 617% achieving rate. After the film was premiered in June 2020, it was extolled on social media and became a long running hit. On April 21st, the film’s Blu-ray and DVD were released. This time, I talked with Makoto Ueda of EUROPE KIKAKU, who has done the script for the film, to hear the stories behind making the film.

——Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes (from hereunder, Droste) is EUROPE KIKAKU’s first-ever original feature-length film—so, how did it come about?

Makoto Ueda (from hereunder, Ueda): EUROPE KIKAKU is mainly active in theatre, and essentially, we’ve also been engaged in video work, such as making a five-minute video for our independent film event Short Short Movie Festival, hosting a medium short film festival Kyoto New Cinema, and creating television programs.

Meanwhile, with our independent films, we got to try out different things and acquired a strong sense of ‘self-accomplishment’; while we unanimously had this broad feeling of “one day we want to make a feature-length film,” a movie theatre in Shimokitazawa, Triwood, and Shimokitazawa Film Festival made us the offer and we took the opportunity to challenge creating a feature-length film.

——Droste is based on the short film HOWLING, right?

Ueda: The representative of Triwood, Mr.Otsuki, liked HOWLING, and he suggested us to turn it into a feature-length film. [Ryota] Yamaguchi, who was the director of the short film was keen about the proposal, and we were able to have him take the helm again for this feature-length film.

——To put out the film, you’ve done crowdfunding—what was your intention behind it?

Ueda: We’ve never done crowdfunding for our plays before, but this time, we wanted to “expand the film”; instead of doing it entirely by ourselves, we thought it would be more exciting to have the viewers participate in the process.

——And you ended up receiving funds from 376 people; raising over 6 million yen.

Ueda: 1 million yen was our goal, so we were astonished. People with common sentiments around what we’ve been doing have supported us and said: “We’re happy to pay if EUROPE KIKAKU is making a film.” We were of course surprised by the amount we ended up collecting, but moreover, we were struck by their spirit.

Writing the script after setting the location

——The location site is used effectively—were you able to find the place swiftly?

Ueda: Initially, I was thinking that we should maybe use the same building as HOWLING, but then I thought it’s probably difficult to rent the entire building. I then found Café Phalam near the building. And the store manager of the café had kindly offered: “The room upstairs and the office are vacant, so why don’t you go ahead and mainly shoot in those rooms?” I’ve also known the barber next door for a long time, so I suggested Yamaguchi: “Let’s shoot in this building”; after the location was decided, I began writing the script. People who saw the film came up to me surprised: “How did you find such perfect location for the film?”—yet it’s because the story was written after we found the building, and not the other way around.

——I also thought the same way as the audience. Regarding the setting of the story— “seeing two minutes in the future through ‘time-tv’”—it was cleverly depicted. Was there a certain calculation to make into two minuets?

Ueda: Including HOWLING, I’ve been writing multiple sci-fi stories, and I’m fascinated by the idea of altering the future within a short amount of time—like one or two minutes. Three minutes feels too long, and probably a minute and a half is the most ideal amount of time, yet that would make the calculation too complex, so I had decided to round it to two minutes exact.

——In fact, the entire story adheres to the setting of two minutes.

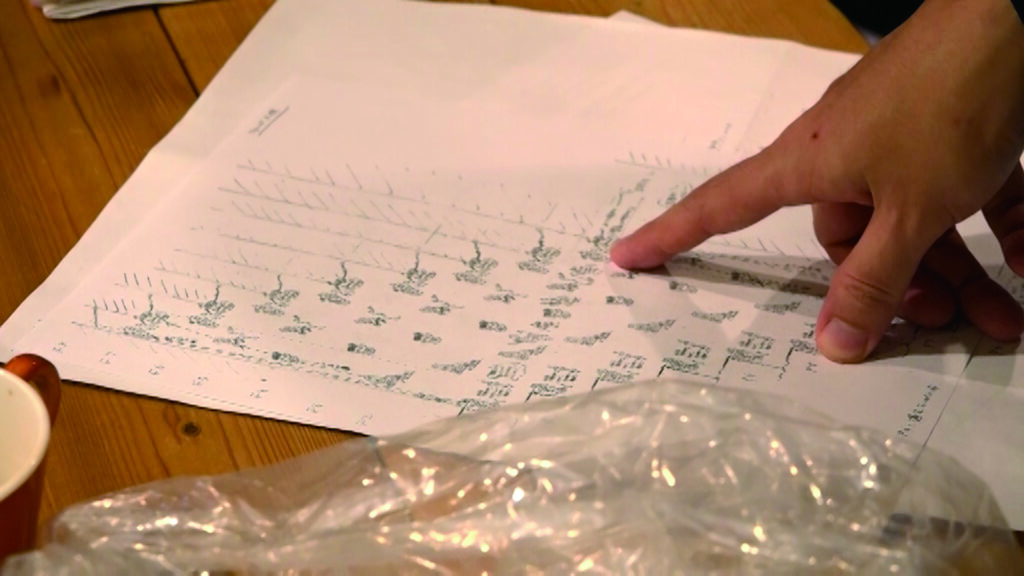

Ueda: The location is in my neighborhood, so I went there by myself to measure time—I went up and down the building and it took about thirty seconds, so I thought the conversation should be about a minute and a half. After I’d roughly determined the length of each cut, I wrote the script; finally, on the set, if the take was too long or short, we made adjustments with the acting speed or by adding and cutting some parts in the script.

——In the film, you show the real images on the ‘time-tv’—did you shoot those footages first before filming the main story?

Ueda: That’s right. We shot the images beforehand to play them on the ‘time-tv’. We had done many rehearsals, wrote down the timecode of each line in the script, and shot accordingly.

——It sounds like a mind-boggling process getting the timings right.

Ueda: It’s similar to making a music video, since you first need to decide the length for each shot. It’s the same thing, and we just had to go by the timecode and determine the timing of every line in the images. However, I wasn’t sure about the overall rhythm of the film and if it would be clear enough to the viewers. Normally, with other films, we can edit the lengths afterwards, but that wasn’t allowed for this film. So, we just had to take the bet and try it.

——You had to film the exact same things as in the images, which means the actors had to speak perfectly the same way as they did in the images. That must have been challenging for the actors, right?

Ueda: It might’ve been so, but they are all stage actors, so I think they’re quite used to performing the same thing repetitively. As it’s a film by a theatre company, I wanted to make full use of our proficiency. Though I must admit it was still challenging [laughs].

We made the entire film almost like a one-shot film—I felt the need to put in everything we’ve been doing as a theatre company or else the film would get buried with many other films out there. I had a strong urge to ‘do something that the people in the film industry wouldn’t think of doing’. Ultimately, a theatrical play runs none-stop for two hours—so long takes are well within our expertise.

——I saw the making of the film and it seemed like there were so many arrangements, and you had to strictly go by the plans.

Ueda: Yes, that’s right. As I’ve never seen a film like ours, it felt rewarding to take up the challenge. If you like the film then you would really like it. If I were the director of the film, it would’ve lacked the filmic context, so in that sense, we were glad to have Yamaguchi in the role since he added the cinematic essence to the film. By the way, the cinematic long take for the opening was also his idea.

——So, when was the shooting?

Ueda: The shooting itself was done last February, and we were scheduling to premiere it in April.

——I have an image that the process of editing takes a little longer than that.

Ueda: I thought so too, but the director gave us the go-ahead. But think about tv dramas: they only take less than a month from shooting to airing on tv—so, I guess it’s possible.

——Last year, due to Covid, the release date got pushed back to June. Also, a lot of people were avoiding to go to the movies because of the pandemic.

Ueda: It was inevitable. It’s ideally the best if a movie earns the most attention while it’s playing in theaters, but there are many movies that unexpectedly gain reputation couple years later or after their DVDs come out. We’ve just put out our first film ever and I think its value is going to grow further as we produce more films in the future—I’m also glad that we have made an achievement of putting it out during the pandemic.

——As EUROPE KIKAKU, would you continue making more feature films?

Ueda: Yes, I would love to.

The difference between real and streaming performances in the world of drama

——Do you think video scripts and play scripts are completely different?

Ueda: Yes, I take them differently. With theatre, the stage is big, and we perform in front of a large audience, so we need to have a lot of people on stage or else the play would lack energy. That’s why I prefer the style of ensemble casting and have as many people as possible on stage. On the other hand, with video work, it’s better to have only one or two people in each frame. And that consequently leads me to elaborate more on a character’s feeling.

——This is off the topic, but as you’ve been based out of Kyoto, have you ever considered coming out to—for instance—Tokyo?

Ueda: I’m not really thinking about moving out of my current base. However, even though I’m in Kyoto, I work with people from Tokyo and travel to Tokyo at times to create things, so it already feels like I’m based in two different locations.

I don’t want to sound nostalgic, but the excitement I felt from back when I was in college has been a big factor in me staying in the same location. Back then, I made decisions by myself and translated them into action. I got to express in ways I wanted to and had a lot of fun creating and preparing for an upcoming performance with my peers. My work is an extension of what I’ve been doing since the old days—although the scales are different, I’m always striving to exceed the joy from back then.

——Since Covid, online streaming has surged, but what are your thoughts on streaming plays online?

Ueda: As I live in Kyoto, I’ve essentially had a lot of opportunities to watch footages of plays. I’m sure there are directors who think that theatrical plays need to be seen live at a theater, but I’m not that against watching plays in a video form. Besides, EUROPE KIKAKU has put out DVDs of its own works before. However, I do think it gets polarized: some plays suit the medium of streaming and some don’t.

When we streamed our play with no audience, we had contrived to make the set look good in the screen by reducing the number of actors and props—But it was possible because there was no audience, and it would’ve been hard if there were spectators in the theater. There is a difference between plays that work well with livestreams and those that are more worth seeing live at a theater; I think this is going to provoke more confusion in the future. To be honest, I’m still not sure whether we should stream our usual performances or not.

——But with streaming, there’s a benefit of allowing you to present plays for people who live in different areas and can’t got out to theaters.

Ueda: Yes, that’s for sure. It’s fundamentally based on the premise of providing an opportunity for people living in different areas to engage with theatrical content. That’s why I think livestreams are beneficial from viewer’s standpoint.

——Finally, the film’s Blu-ray and DVD are coming out—what types of people would you like to have the film seen by?

Ueda: Although I’m in the field of theatre, I like to enclose and secure the passion born from performances into images. I like the idea of packaging drama into a Blu-ray or a DVD. Our latest work, Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes (Droste), is not a theatrical piece, yet I enjoyed preserving the moment’s energy into images—And turning it into a Blu-ray and DVD is the best thing that could ever happen to it. Nowadays, there is streaming, so I’m sure there are people who don’t feel the need to own disks. However, with Droste, we have put strenuous effort to package the hell-like times we’d spent together and miraculous moments into the most gleaming form—So, I would love for every home to have one.

——And the DVD is lavish with exclusive contents, too.

Ueda: The Blu-ray also features making of the film, short film Howling, and furthermore, there are three pieces of commentary [laughs]. It’s so rich in contents, so I would love for people to enjoy those along with the main content.

Makoto Ueda

Playwright / director / planner of TV/radio programs. Born on November 4, 1979 in Kyoto Prefecture. He is the representative of the EUROPE KIKAKU and in charge of playwriting and directing all the performances of the company. He also writes scripts for theatrical plays, films and dramas; and serves as the planner of TV and radio programs. Since 2003, his works—Winter Uri Geller, Surrounding Formation, Mediocre Way, and Windows5000—have been selected as final candidates at the OMS Drama Awards. In 2010, he contributed as a planner and screenwriter to the TV anime The Tatami Galaxy, which won the grand prize in the animation division of the 14th Japan Media Arts Festival. In 2017, he won the 61st Kishida Kunio Drama Award for Shinsekai to Come and Go.

http://www.europe-kikaku.com

Twitter:@uedamakoto_ek

Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes (Droste)

In addition to the main content—which has been remastered in pursuit of high picture quality under the supervision of director Junta Yamaguchi—both Blu-ray and DVD include three pieces of commentary. Blu-ray also includes ‘The Full Version of Making of Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes (Droste) (with a commentary)’ which features unprecedented long takes of the film, the short film Howling which is the original draft of the film in subject, a soundtrack CD supervised by Koji Takimoto, and a booklet ‘Dictionary of Droste’ that covers everything behind the scenes. At the same time, distribution will start on iTunes, Amazon Prime Video, and otherwise.

http://europe-kikaku.com/droste/

Photography Mayumi Hosokura

Translation Ai Kaneda