On September 24th, 2021, manga artist Takao Saito passed away from pancreatic cancer at 84. That his popularity didn’t wane in the turbulent manga industry since his debut in 1955 is impressive. Moreover, for over 60 years, Saito continued to be at the forefront of gekiga, a manga genre geared towards adult readers. Not only that, he founded his own publishing house and manga production company called Saito Production, which was rare for its time. As such, he was a leading figure in the industry who paved different ways.

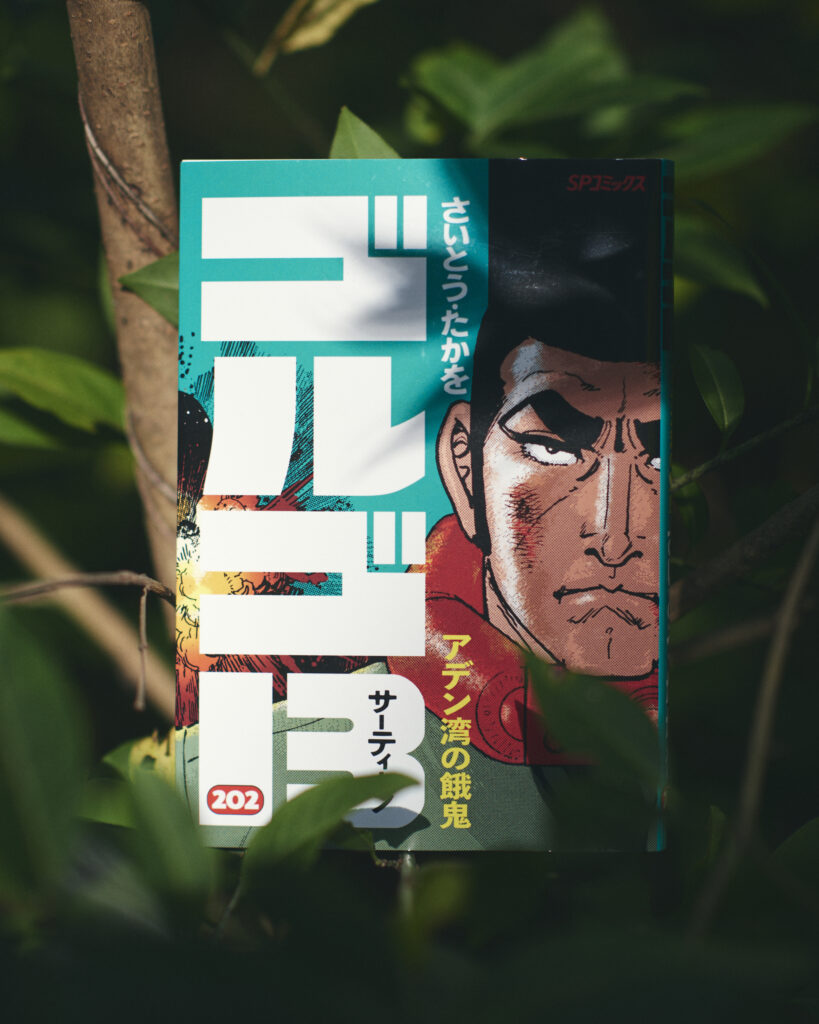

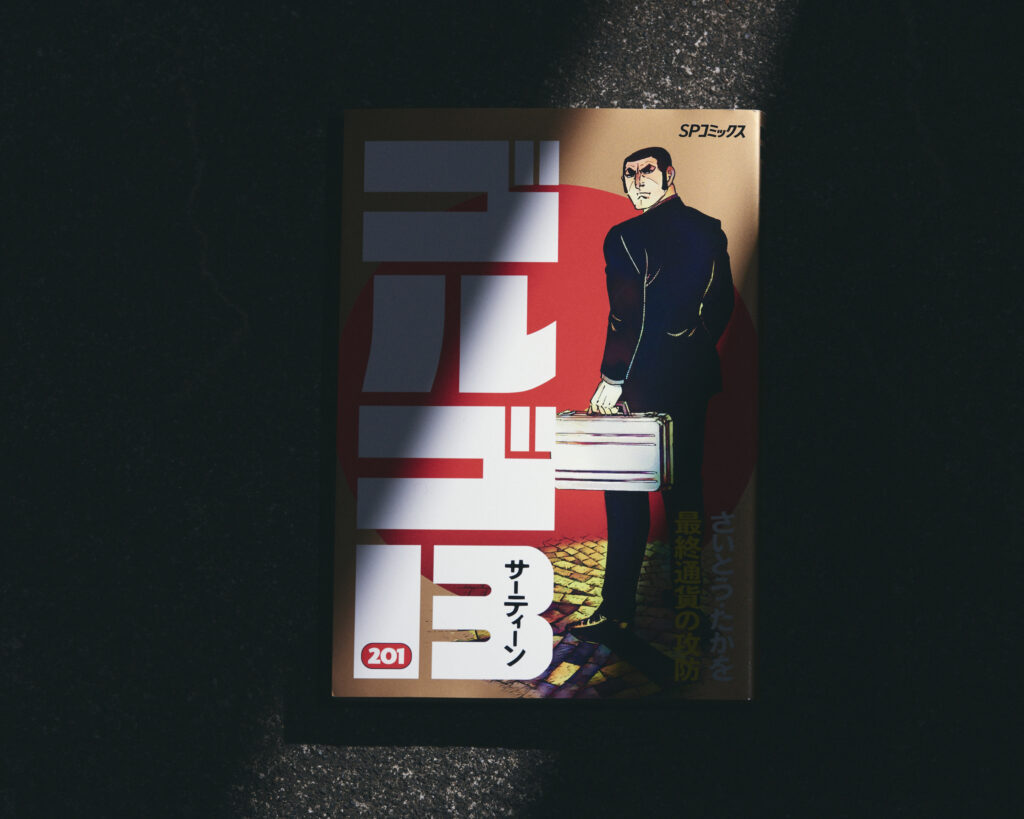

Saito’s most famous work is Golgo 13. This manga, which started becoming serialized in 1968 via Big Comics (Shogakukan), set a new Guinness World Record for most volumes for a single manga series this July. 202 volumes have been published thus far and are a testament to its longevity. Saito’s staff have inherited his dying wish to continue publishing the series posthumously.

I’d like to reflect on Golgo 13, probably the first and last manga with an assassin as the protagonist to be described as a national treasure.

The birth of Golgo 13 during the cold war

Golgo 13 became serialized in 1968, at the height of the cold war. In such an era, assassins and spies who worked behind the scenes across western and eastern countries were, in a sense, part of reality.

The protagonist is Golgo 13 (Duke Togo). He’s a top-tier sniper whose real name, nationality, and age are unknown, naturally. The series is composed of short, complete stories where Golgo 13 receives an exorbitant reward from clients across the globe to get the job—assassination—done. At times, he finds himself to be the target or goes on a treasure hunt-like adventure.

The targets of Golgo 13 are usually criminals or problematic individuals in politics and the military. The tension and anxiety readers shared during the cold war made the series feel lifelike in the 70s and 80s. That is, people feared that a third world war might happen. Also, many people admired the protagonist—who was thought to be of Japanese descent—because the States or the Soviet Union didn’t tie him down.

The manga, then, should’ve been discontinued once the cold war was over, but it’s common knowledge that it continued being published after the cold war ended in 1989 (or the early 90s). Why is that?

The protagonist’s uncompromising way of living

One plausible reason is how Golgo 13 never became irrelevant even after the cold war ended. It’s almost unnecessary to bring up 9/11, as even today, the world is rife with terrorism, war, and conflict, and crime is technologically evolving. In this context, one can say Golgo 13’s scope is diversifying.

Further, the shape of evil was lucid during the cold war, but thanks to the complexity of the international state of affairs today, it’s out of sight. Back then, the west viewed the east as evil and vice versa. Golgo 13 is a hitman unique to the times we live in, in which the black and white structure of enemy and friend is gone. After all, the “bad guys” haven’t disappeared from the world; they just deftly hide from the spotlight. Meaning, the series still holds water today.

Another reason: the most vital thing in manga-making is creating a memorable character. You could say the intense individuality of Golgo 13 (Duke Togo) has rendered this story a universal one. He sticks to his beliefs until the end, without being swayed by others, regardless of the era and situation.

For instance, in Jouhouyugi, Golgo 13 says the following to a person in a massive organization that’s trying to bring him in: “I… have no intention of working with a particular client, no matter how powerful they are…” (Volume 117, LEED Publishing/SP Comics). In SoukouheiSDR2, he says the following to military personnel who wields “American justice”: “Isn’t the justice you speak of justice only for yourselves?” (Volume 148).

Golgo 13’s unwavering way of living has continued to appeal to us with conviction, from the cold war to the covid crisis. That’s why Golgo 13 attracts readers’ adoration and empathy in any era, despite the protagonist being a sniper and outlaw that lives in a world of darkness.

The division of labor, a new manga-making system

Takao Saito had been able to produce a colossal amount of gekiga, Golgo 13, over the years because, as I mentioned before, he founded a production company for manga in 1960, which was rare for its time. The work had been divided into roles as well, from the script, composition, to illustration. Even within the drawing department, the characters, guns, buildings, machines, and small objects were drawn by different people.

Today, it’s the norm for different people to work on the original draft and final product or for several assistants to help a manga artist. However, when Saito debuted, manga artists usually worked on everything on their own, from the conceptualization to the finishing touches. Of course, manga artists back then might’ve had a friend give them a helping hand right before the deadline.

For Takao Saito, manga (gekiga) wasn’t something one genius produced. Long ago, he had developed the view that several people could gather and utilize their skills/craft to create a manga. This is what led to the mass production of high-quality entertainment. By deciding to publish the manga posthumously, he achieved the ultimate manga (gekiga) production system.

What’s interesting is how Saito wasn’t in charge of the script or drawing—he was in charge of the structure and composition. Usually, aspiring manga artists desire to write a story or draw manga. But Saito was different. Perhaps this stems from the fact that he was drawn to not the manga industry, but the film industry. He tried to make a film on paper as a director. “Name” refers to a rough draft of a manga with comic frames and lines, which is the same as coming up with the structure and composition of a manga. This, in turn, is the equivalent of creating a storyboard, which is what most film directors do.

A message to the youth living through the pandemic

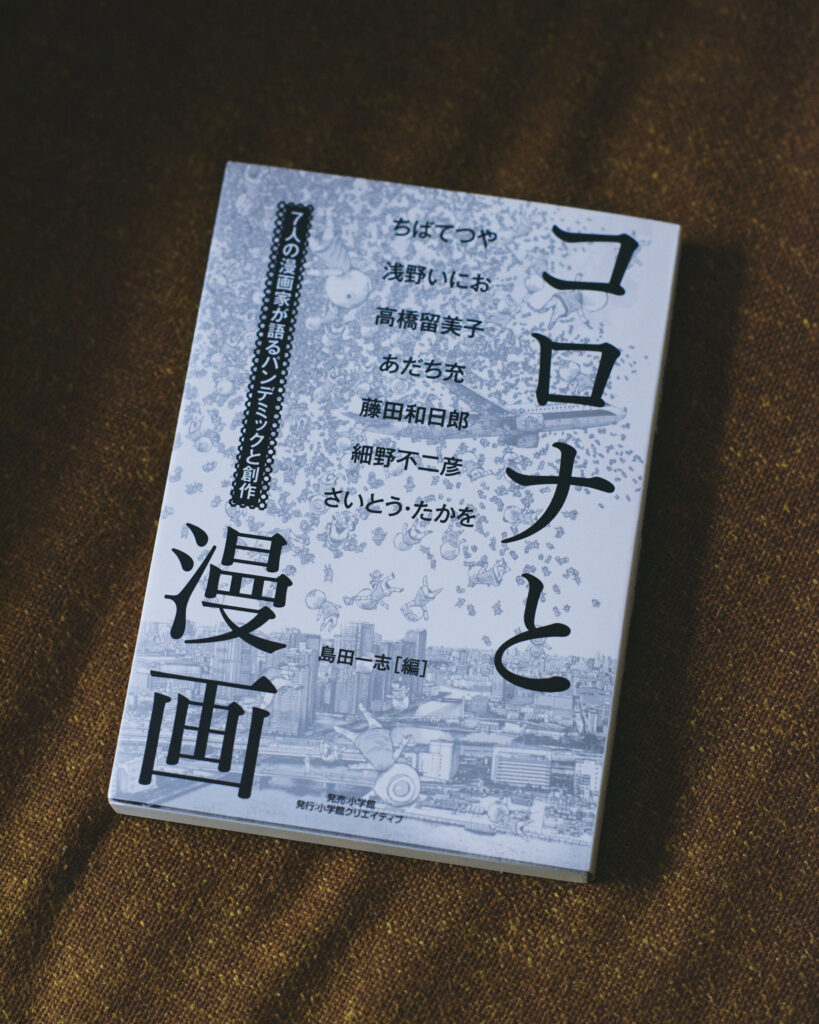

Lastly, I’d like to get a little personal with you. A compilation of interviews in which I acted as the interviewer, Corona to Manga〜7ninn no Mangaka ga Kataru Pandemic to Sousaku, came out recently, and an interview with Takao Saito is included too. I haven’t checked if this is the maestro’s last interview, but there’s no doubt that it’s one of the most valuable ones of his final years. It took place in July this year over a series of emails, which I later edited into an interview format.

I’d love for you to read the book for more details. Alongside insightful anecdotes about work, Saito gave a message to young people living right now during the pandemic. I’d like to take this opportunity to share an excerpt from it:

“Golgo himself has experienced many dangerous situations and has escaped them countless times. I hope people could feel something from how he doesn’t adhere to prejudice or stereotypes, examines various possibilities, and stands up without giving in.

“At any rate, I think the biggest thing I can personally do during this era of the pandemic is to continue drawing Golgo 13. I want the young people reading this to not give up their studies, work, and fun because of covid, and to do their best for a while. I want to see the world post-covid, which will come one day, with them.” From Corona to Manga〜7ninn no Mangaka ga Kataru Pandemic to Sousaku by Kazushi Shimada (Shogakukan Creative).

Photography Yohei Kichiraku

Translation Lena Grace Suda