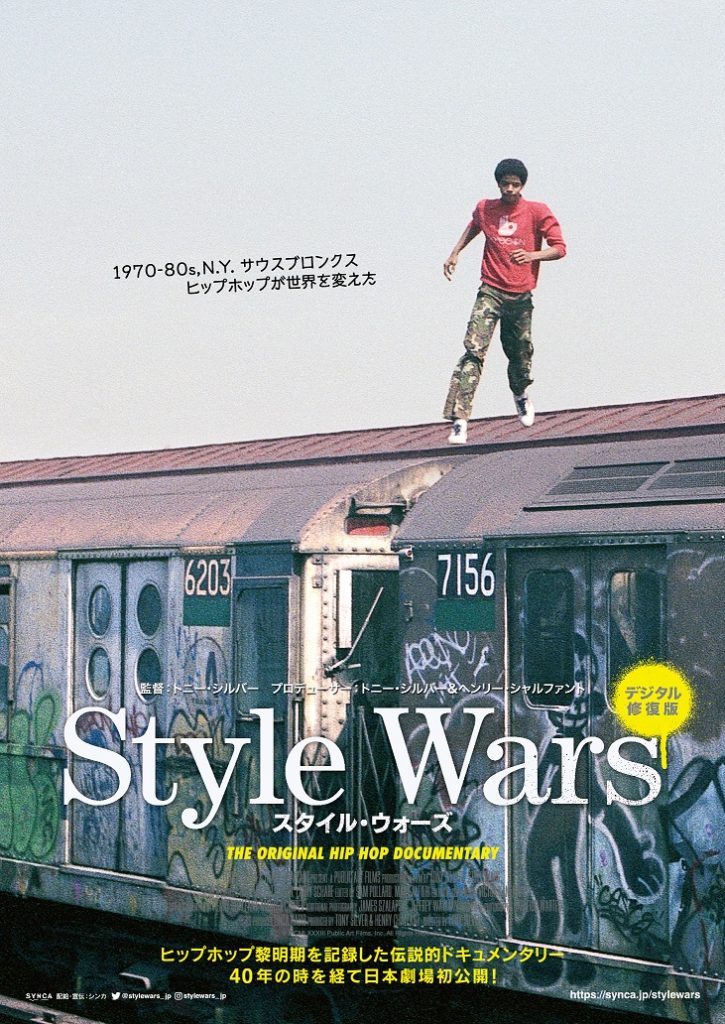

On March 26th, “Style Wars” will hit Japanese theaters. With an emphasis on the graffiti coming out of the South Bronx in the 1970s and early 1980s, this documentary film captures rap, breakdancing, and the birth of hip-hop. Starting with Shibuya’s White Cine Quinto and Shinjuku Musashino-kan, the film is scheduled to gradually be released nationwide in Japan.

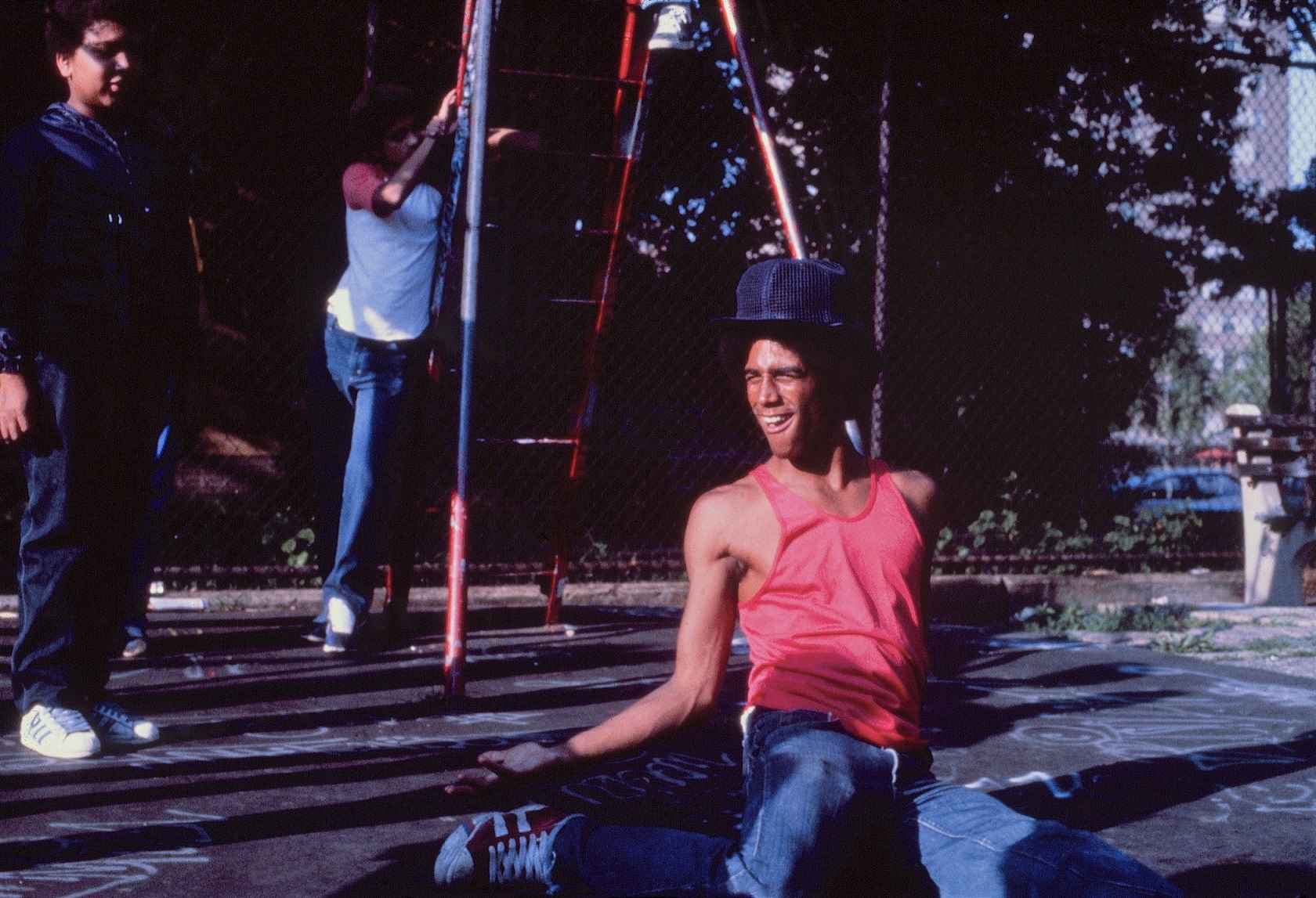

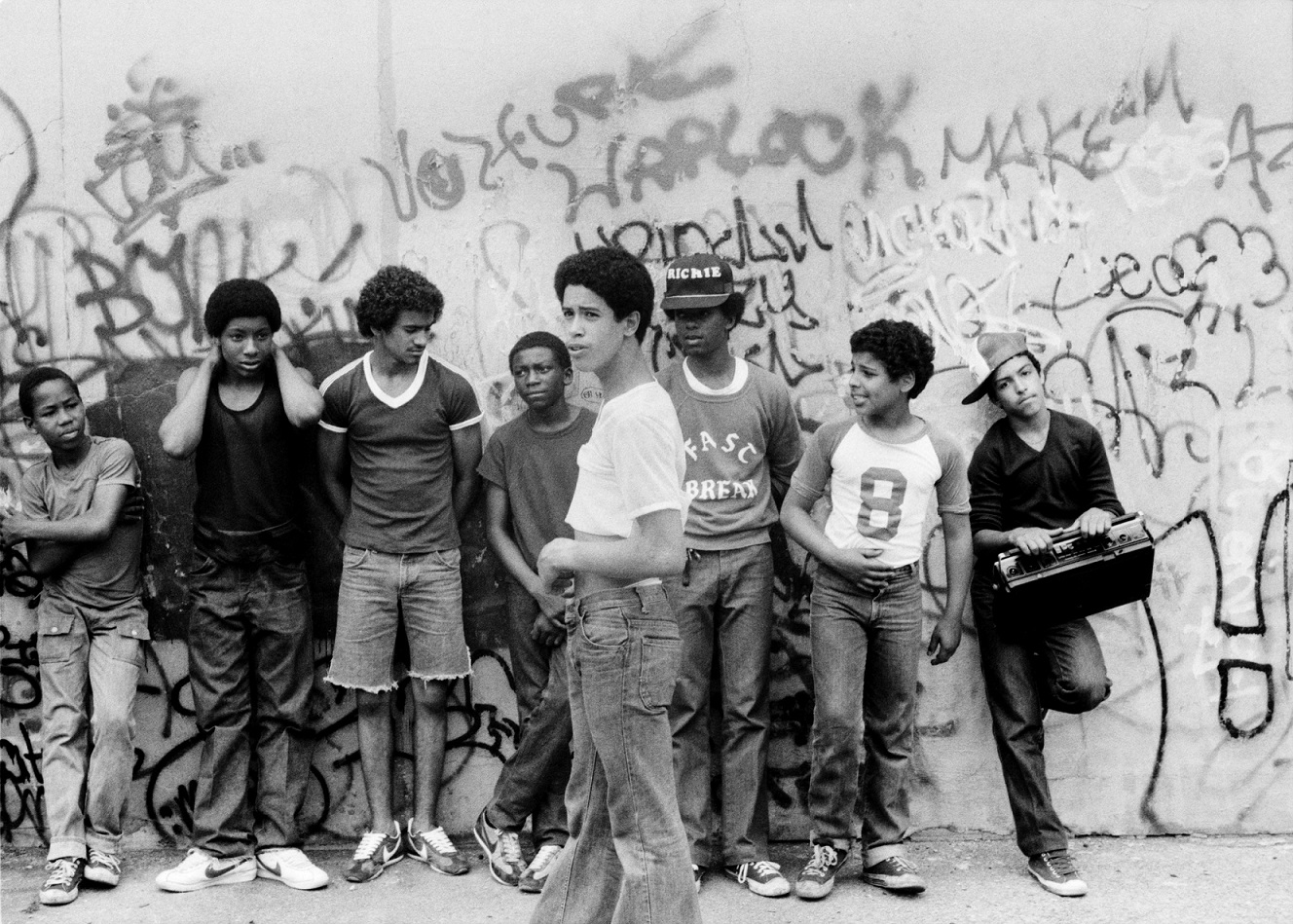

Referred to as a “hip-hop head bible,” “Style Wars” has been passed down, along with “Wild Style,” as a film that reflects the early days of hip-hop. In the early 1970s, a time when poverty and crime were two sides of the same coin, hip-hop was born as a new subculture for young people in the Bronx to make their mark. This film captures not only the atmosphere of an era in which a new movement was born, but also the vibrancy of young people who were driven by an indescribable urge, despite criticism from adults who reduced their art to vandalism. 40 years since the film’s creation, it still brings fresh surprises and discoveries. We interviewed photographer Henry Chalfant, who co-produced “Style Wars” with Director Tony Silver. By learning about the film’s background, we hope viewers can enjoy the film while thinking back to the time of its creation.

Furthermore, official merchandise from “Style Wars” will be available on the TOKION site and TOKiON the STORE. The T-shirts and hoodies, which feature the classic “Style Wars” logo with the names of the graffiti writers who appear in the film printed on the back, are must-haves for any fans.

1983/USA/70minutes

Model Yua,Jion

Why Henry Chalfant documented this youth culture in 1970s New York.

――When you moved from California to New York in the early 1970s and experienced the graffiti and hip-hop scene in the South Bronx firsthand, what did you think?

Henry Chalfant: I was already interested in subway graffiti, so when I first moved to New York City, I was constantly taking photos of the graffiti in the South Bronx from the early morning. After meeting the Rock Steady Crew and Fab 5 Freddy in around 1978 or 79, and Rammellzee in 1980, I understood that hip-hop and graffiti were inextricably linked, making up one larger culture.

――At the time, you were involved in events downtown, right?

Henry: I held graffiti photo exhibition downtown with Fab 5 Freddy and Lee [Quiñones]. That’s how I met Charlie Ahearn [Director of “Wild Style”], who was already working on “Wild Style” and was going in and out of clubs in Harlem and the Bronx, so he taught me about hip-hop culture. At first, I was only interested in graffiti, but once I was exposed to the youth culture they called hip-hop, I was immediately hooked.

――Why did you start shooting graffiti?

Henry: After moving to New York, I realized that graffiti styles were evolving at a really fast pace. I was motivated to document the new culture that young people in New York were creating and to show off the youth movement that was happening here. And as a photographer, I also genuinely wanted to communicate that through photographs. But Manhattan’s subways are dark and difficult to photograph, whereas in the Bronx, they run above ground, so they’re easy to shoot.

――Did you discover anything from shooting the subways that run above ground?

Henry: The 2, 3, 5, and 6 trains were important for graffiti, and they ran from north to south—from the Bronx to Manhattan and Brooklyn. This meant that the sides of the subway cars caught the light easily. If I took photos in the morning, the sun would light up the subway cars nicely, which made for much better photos. If the trains ran east to west, I don’t think I could have gotten those shots.

It all started in 1981 at a rehearsal for a breakdancing event that never came to fruition.

――Did you find yourself in any dangerous situations while shooting? How did you build relationships with the graffiti writers?

Henry: At the time, it was much more secretive than today, and graffiti wasn’t even legal, so I did face the risk of being arrested by the cops. One memory that stands out is how these kids would watch me shoot, but wouldn’t talk to me at all because they suspected I was a cop. After two or three years, I finally got to know them, and the kids who saw my photos started to respect me. When I talked to them about exhibiting their work, they opened up to me because I was a photographer who recognized their talent. But also, there were times when I was meeting with some graffiti writers at my studio, and an opposing crew showed up and a fight broke out.

Also, back then, you needed a permit from New York City to take photos on the subway. I would have had to go to Brooklyn to get it, so I wouldn’t go pick it up every day, and sometimes the cops would stop me. When that happened, I’d pretend that I was a teacher and say it was for a school project.

――You made “Style Wars” at a time when there was criticism of graffiti films. Your film was shown on TV in 1983, and then up until now, it was distributed through bootleg copies. This film has become a valuable documentation that’s introduced graffiti culture to countries all over the world—but why did you think to document graffiti in the first place?

Henry: Because I recognized graffiti as a valuable art form. In 1981, I was supposed to put on an event downtown called “Graffiti Rock” that introduced breakdancing to the public for the first time. I invited Rammellzee and Fab 5 Freddy as rappers, and their friends were supposed to DJ. But then during the rehearsal, some guys from a rival gang showed up at the venue, and some of them had guns and knives. The venue owner ended up canceling the event itself because they didn’t have insurance for a shooting. But Tony Silver was at the rehearsal, and after that, he asked me if I wanted to make this documentary. That’s how the film started. Of course, I’d had the idea to make a film, too. I just didn’t know how. That was Tony’s role. Mine was like that of the ethnographer.

I think it was such an amazing collaboration because we had a really complementary relationship. Tony shot the subway operators, the mayor of New York City, and everyday New Yorkers from an outsider’s perspective, while I reflected the views and opinions of the graffiti writers and kids as an insider.

――At the time, artists like PHASE2 and Rico 1 were holding solo shows in Soho. Are there any shows or performances that were particularly memorable?

Henry: When I moved to New York in 1973, PHASE 2 and Snake 1 were showing at Laser Gallery in Soho. Those guys were already painting on canvas at the time, which left an impression on me. Also, there was an amazing performance where a group of black graffiti writers were tagging flags behind the choreographer Twyla Tharp’s dance team. This event was before hip-hop came about though, so they were playing rock music there.

What teenage energy created in a dangerous, impoverished environment.

――Today, musicians from all over the world incorporate rap into their songs, the Paris 2024 Olympics added break dancing as a sport, and Banksy’s works are auctioned off at high prices. Looking back on the early days, do you have any feelings around today’s graffiti or hip-hop scene?

Henry: Hip-hop culture has become commercialized. I think graffiti still has that rebellious, anti-establishment spirit to it. I think that spirit is necessary for youth culture. But as the world becomes more commercialized, things like the fashion, which kids were creating with what they had, are now at the center of the marketing strategy for luxury brands. We should enjoy change, and I’m not a fundamentalist, so I don’t have a nostalgic view that the old days were better. My only impression is that the times have changed.

――With the film being shown again in theaters nearly 40 years later, what do you want viewers to feel?

Henry: That graffiti and hip-hop culture, which no one even knew at the time, was made by teens. Back then, a lot of buildings in the Bronx were falling apart or burnt down, and except for one section, New York was really poor. It was dangerous everywhere, but the kids were brave enough to create a new culture. And even though they weren’t living a materialistic lifestyle, they made an amazing culture that still lives on to this day. I think young people from all over the world were inspired by that energy, and the culture quickly spread across the world. I hope the viewers feel that.

Originally a sculptor, Henry Chalfant turned to photography after encountering graffiti in New York in the 1970s. He has over 1500 photographs documenting graffiti art, and his graffiti archive is on display at the Eric Firestone Gallery in New York and East Hampton. He has also written books on the subject, including “Subway Art,” (Holt Rinehart Winston, N.Y., 1984) which he wrote with Martha Cooper, and “Spraycan Art” (Thames and Hudson Inc. London, 1987). His documentary film, “Style Wars,” was broadcast on TV in 1984, and later screened at film festivals including the Sundance Film Festival. Today, nearly 40 years later, the film will screen in Japan for the first time. Starting with Shibuya’s White Cine Quinto and Shinjuku Musashino-kan, the film is scheduled to gradually be released nationwide.

■“Style Wars”

Date: March 26th

Venues:WHITE CINE QUINTO, Shinjuku Musashino-kan, and more.

Address:WHITE CINE QUINTO/Tokyo, Shibuya City, Udagawacho, 15-1 Shibuya PARCO 8F

Shinjuku Musashino-kan/Tokyo, Shinjuku City, Shinjuku 3-27-10 Musashino Building 3F

Website:https://synca.jp/stylewars/